Today, with such high-powered craft as the Momus, storm and stress of weather have practically no effect on their progress, and sea voyaging becomes a delight. These great new ships of the Southern Pacific are wonders in their way, and travelers in general should get better acquainted with them. Indeed traveling on ships like these rob the sea of all its terrors; they remain on an even keel through the most boisterous ocean weather. Not only are these new steamers large and of deep draught-- features so essential to modern sea voyaging-- but they have power, plenty of it and in reserve, which enables them to adhere closely to their schedules, no matter what the circumstance.

The Nautical Gazette, 23 December 1909.

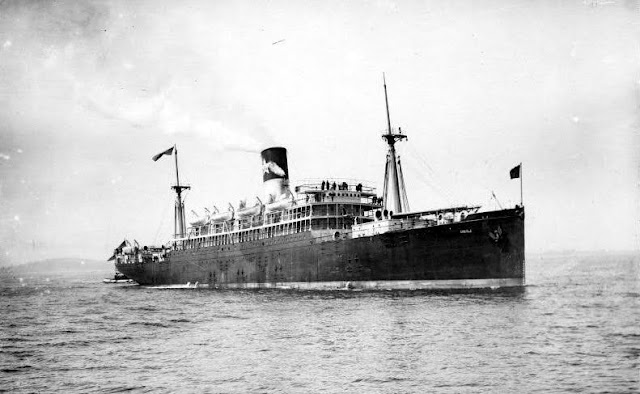

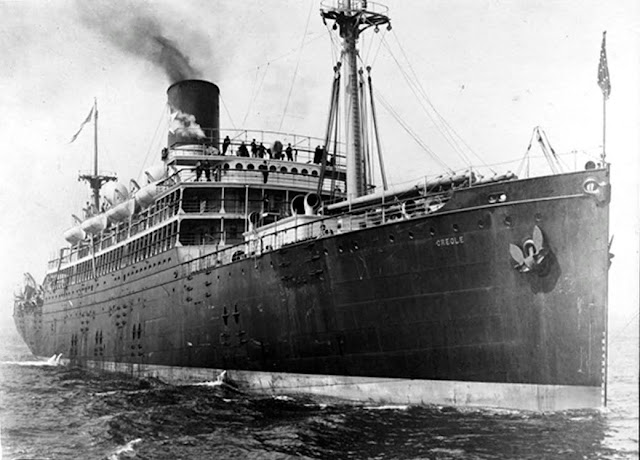

Dubbed "100 Golden Hours At Sea," for 75 years one of the longest and most popular of the myriad steamship services that once linked American coastal cities on both coasts, that between New York and New Orleans-- from North River to Mississippi River-- was for a quarter of a century served by the biggest trio of American coastal liners ever built: Momus, Antilles and Creole. Introduced in 1907-08 at the end of the great Harriman Era of the Southern Pacific, they represented the pinnacle of a unique rail-sea link to the American Southwest and West and state of the art of Yankee shipbuilding and marine engineering of the period.

Momus, the favored, put in a quarter of a century of service; Antilles, the fated, was the first American transport sunk in the First World War; and Creole, the flawed, was the first American twin-screw turbine-powered liner and, as such, a failure that, once re-engined, redeemed herself with more than two decades ensuing service. Collectively, the three sailed through more hurricanes and tropical storms than any vessels of their age and served their owners faithfully some 60 years, "100 Golden Hours At Sea" at a time.

Join us on a trip "Out West" by coastal steamer and trans-continental railroad, aboard

s.s. MOMUS, ANTILLES & CREOLE

|

| Momus, after conversion to oil-burning in 1921 and a new funnel, making speed. Credit: eBay auction photo. |

|

| S.S. Momus by Fred Pansing. Credit: Sunset magazine, 1910. |

In the matter of sea connections, New Orleans is peculiarly well served. In this connection, the Southern Pacific Company played a prominent part by popularizing the sea trip between New York and New Orleans as part of a trans-continental journey. This sea service developed into an extensive freight and passenger business, the boats operating under the name of the Morgan Line.

Great care has been exercised in the design of the vessels placed upon this run, as the passenger traffic had to be stimulated through the provision of every comfort and luxury. The boats were fitted to meet the conditions prevailing in the semi-tropic waters through which they were to run ad a building program that called for bigger and better boats with each addition to the fleet was strictly adhered to.

Pacific Marine Review, April 1917.

Harriman immediately made good a pledge to spend money in the amount necessary to realize Southern Pacific's potential.

The Southern Pacific, 1901-1985.

As recounted in more detail in the monograph on Dixie on this site, Charles Morgan (1795-1878) is credited with creating the rail and sea infrastructure of the American Southwest and in doing so, established the first sustained coastal steamship service in the country and, under the Morgan Line, regular passenger and freight operations linking New York and New Orleans beginning in 1876.

When Southern Pacific Railroad bought out Morgan Line in 1885, it soon realized the greatest potential of what Charles Morgan had already pioneered: the intermodal rail-sea transportation system that networked the South and linked it with New York by sea. Now connected directly with Southern Pacific's newly opened trans-continental railroad (which first ran from San Francisco to New Orleans in February 1883), Morgan line helped span an entire nation.

Southern Pacific was favored by two leaders at its onset possessing such dynamic, driven qualities as to stamp their enduring mark on it: Charles P. Huntington (1821-1900) and E.H. Harriman.

Under Harriman, S.P. Atlantic Coast Lines operation (which still traded as "The Morgan Line") was first strengthened by expansion through acquisition, in particular that of Cromwell Line in 1902 which ran a first class passenger service from New York to New Orleans with the 4,900-ton Comus and Proteus which were the first modern liners on the route, and the famous flyer Louisiana (2,900-grt) which held the speed record on the route for years. Huntington commissioned a new fleet of El-class freighters in 1901-02, both for the New Orleans run and the new service from Galveston to New York, directly competing with the long established Mallory Line. In 1903, a new route was established from New Orleans to Havana, Cuba. That year, too, Southern Pacific moved its New Orleans terminal operation across the Mississippi River from Algiers to New Orleans proper for which new wharves were built by 1905.

Momus, Antilles and Creole owed their inspiration and creation to three of the many great Americans of finance, industry, shipbuilding and engineering of the early 20th century: President Edward Henry Harriman (1848-1909) who was president of the company (in addition to the Union Pacific Railroad) from 1901 to his untimely death at age 61 in 1909 and one of the great giants of American industry and finance; Admiral Francis Bowles (1858-1927) naval constructor and head of the Fore River Shipyard naval architect and C.W. Jungen (1859-1934), manager of Southern Pacific Steamship Co., from 1905 to 1928.

|

| Edward H. Harriman (1848-1909). Credit: wikipedia |

Harriman had already demonstrated his expansionist qualities with Union Pacific and indeed his coming to also head Southern Pacific was with the real intention, not achieved until 1996, of facilitating the merger of the two great railroads. In the dawn of a new American era of technical and engineering achievement and innovation, he was quick to embrace them, championing new means and methods on a wide enough scale to prove or fail them. So it was that there were Harriman locomotives and Harriman coaches and his very name came to symbolize innovation and rationalization along modern and efficient lines throughout the whole enterprise, ashore and afloat. Harriman's management of Southern Pacific realized the full potential of its unique intermodal rail-sea freight and passenger transportation system pioneered by Henry Morgan and furthered by C.P. Huntington who acquired the Morgan empire in 1885.

|

| Credit: Sunset magazine, August 1903. |

With the acquisition of the Cromwell Line in 1902, the passenger traffic on the New York-New Orleans route flourished, spurred by an intense advertising campaign for "The Sunset Route" out West by S.P. steamer to New Orleans and the premier Sunset Limited trans-continental train. Proteus and Comus, fine and capable ships of 4,828 grt, 392 ft. by 48 ft., had a passenger accommodation of just 50 First Class and 190 steerage, and demand for the service caused sailings to be sold out months in advance. Then, too, demand for the new route to Havana, Cuba, further taxed the existing tonnage. By the end of 1903, Harriman turned his expansionist zeal to what was becoming an increasingly important part of his Southern Pacific empire. It was time for Harriman Sister Ships, initially envisaged as a pair then a trio, that would elevate S.P's Atlantic Steamship service to the pantheon of American coastal route and in doing so, put the Harriman stamp on the operation.

|

| F.T. Bowles (1858-1927). |

|

| Credit: American Society of Naval Engineers, via wikipedia. |

Figuring large in Harriman's decision to build all three ships but especially in regards to the propulsion system of one in particular, Rear Admiral Francis Tiffany Bowles (1858-1927) was rightly called the Father of the Modern American Steel Navy as Chief Constructor of the U.S. Navy from 1901-1903 during which time he became intimate with American shipyards and practices of the era, in particular that of the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy which was at the forefront of naval design and construction including the first submarines and many contracts for foreign navies, not the least of which was the Imperial Japanese Navy.

|

| Charles Gordon Curtis (1860-1953). Credit: wikipedia |

In an age of constant invention and innovation abetted by the fearless application of capital to develop and prove new modes and techniques in practical use, it was perhaps inevitable that the paths of Harriman and Boyles should cross and have at their nexus, the steam turbine developed by Charles Gordon Curtis (1860-1953) in 1896. This combined the qualities of the Laval and Parsons turbines into a multi-stage impulse turbine that was smaller and more straight forward in design than the proven Parsons turbine and did not require a separate reserve turbine in maritime applications. Curtis had little fortune in marketing his invention until he sold the patents to Edwin W. Rice of the General Electric Co. 1901 and it quickly became widely used in electric power generating plants. Its maritime use, however, lagged until F.T. Boyles gained the construction rights of the marine version and immediately began to lobby the U.S. Navy to install it in two Chester-class cruisers Fore River was building as well as battleships.

The development work of the year on the Curtis marine turbine has been on the whole very encouraging to the directors, and it is their belief that the exclusive option held by the company on marine rights of this turbine for this country will prove of great value in the future. The principal turbine contracts so far obtained by the company are for the construction of the U.S. scout cruiser of 3,750 tons. the Southern Pacific S. S. Creole of 10,000 tons, and for the construction of turbine equipment for two large vessels. The Creole will be completed in the near future, and if the trial of this vessel fulfills the expectations of the management there will undoubtedly be a demand for further vessels fitted with Curtis turbines , which should be of great benefit to the company.

Annual Report of Fore River Shipbuilding Co., The Marine Review, 28 February 1907.

Navy boards took longer to convince and Boyles found an more immediate and eager customer for the Curtis turbine in E.H. Harriman, never one to dismiss new technology but canny enough to ensure specific contractual obligations so as to not be saddled with failure. So it was that Southern Pacific's plans for a pair of new ships, already well in hand in 1905, was extended to include a third, to be built at Fore River and be propelled by the Curtis turbine. As such, it would be the first American twin-screw turbine-powered merchant ship. At a stroke, Harriman's new ships assumed the public relations primacy as America's wonder ships, representative of the marvelous new century and expression of native engineering and naval architecture genius.

|

| J.W. Jungen (1859-1934). Credit: The Nautical Gazette, 1920. |

As a Lieutenant in the U.S. Navy, C.W. Jungen was a survivor of the explosion which destroyed U.S.S. Maine in Havana harbor in 1898 and went on to serve with distinction in the ensuing Spanish-American War, cutting the submarine cables at Santiago as commander of the tug Wompatuck. Although remaining in the U.S. Navy Reserves until 1912, Jungen left the active service in 1904, at the rank of Commander, and was appointed manager of Southern Pacific Atlantic Coast Steamship Lines late that year.

The accidental sinking of the Morgan Line's famous Louisiana (1879), long the holder of the record on the New York-New Orleans run, at her berth in New Orleans in April 1905, and her subsequent total loss, spurred plans already well in hand for a new fleet of much larger, both in passenger accommodation and cargo capacity, ships for the route as well as to potentially serve on the new route from New Orleans to Havana. On a visit to New Orleans on 24 May, Jungen was quoted by the Houston Post as "practically ready for letting contracts for two new steamers, which will be done in a few days."

On 12 July 1905, President E.H. Harriman of Southern Pacific signed a contract for one 6,000-ton turbine-powered liner with the Fore River Shipbuilding Co. of Quincy, Massachusetts. As reported by the Quincy Daily Ledger, "This craft will operate on the Morgan Line between New York and New Orleans, and will be, when completed, by far the largest turbine propeller ship built in America. President Bowles has been an earnest advocate of the turbine propulsion and last year made proposal to build for the government the most powerful class of warships with turbine machinery. His contract with Mr. Harriman marks the first important venture into the field of turbine navigation for commercial purposes in the United States. The new ship will be equipped with turbines of the Curtis type, and will have a speed of 16 knots an hour."

The Philadelphia Inquirer of 9 August 1905 reported that "The Cramps have secured contracts for four steamships of 10,000 tons each, two for the Southern Pacific Company and two for the New York and Cuban Mail Steamship Company…" It added that "the steamers for the Southern Pacific Company will be sister ships, 410 feet in length, 53 feet beam, 25 feet draft and have a speed of 16 knots. Counting the promenade deck, there will be six decks. Power will be supplied by single screw, triple-expansion engines of the reciprocating type, steam being supplied by tubular Scotch boilers. Electric heaters will be placed in the state rooms and they will be the first vessels so equipped for the coast service." The keel of Creole was laid down in August.

Southern Pacific announced a naming contest for the three new ships on 26 August 1905, with a top prize awarded of $100 for all three ships,or $25 for one winning name selected. "I do not think we want foreign names such as grace our freight vessel. The El Sid, the El Pazo and all the other Els are well enough for freighters, but we want our new passenger ships to have American names," said the Southern Pacific representative in making the announcement, The contest would close on 30 September. It was announced at the same time that two of the new ships would go on the New York run and the third on the Havana route, effectively doubling sailings on both services. After receiving 1,353 letters of suggestions (6,000 in all), Southern Pacific announced on 23 October 1905 that the new ships would be named Momus, Creole and Antilles.

|

| Credit: Country Life in America, December 1906. |

1906

The launching was one of the most successful that has ever taken place at this plant, and was witnessed by a large number of prominent persons.

The Brooklyn Citizen, 1 August 1906.

Momus, with a launch weight of 3,500 tons, was launched at 10:08 a.m. on 31 July 1906, christened by Mrs. C.W. Jungen, wife of the manager of Southern Pacific Steamships. The christening party consisted of C. W. Jungen and wife, E. T. Stotesbury and George McFadden, directors of Cramps; L. H. Nutting, general passenger agent of the Southern Pacific Company;W. F. Fairburn, superintending engineer, and wife; W. C. Parker, auditor of the steamship lines of the Southern Pacific Company, and wife; and Captain Frank Kemble. At the post launching luncheon that followed, "Mrs. Jungen was given a pleasant surprise by being given a handsome diamond studded bracelet, suitably inscribed, by the shipbuilding firm as a reminder of the occasion. (Philadelphia Inquirer).

Sliding from the ways shortly after 10 o'clock yesterday morning, the steamship Momus, which is to be used by the Southern Pacific Company, was launched at the yards of the Cramp Shipbuilding Company upon the Delaware River.

With straight aim, Mrs. Katherine Woods Jungen, wife of the general manager of the owner of the boat, smashed the bottle of christening wine upon the prow of the vessel, just as it was gliding into the river.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, 1 August 1906.

The launching of the Momus was a most successful one. Hardly a ripple was caused on the water as the immense vessel glided from the ways. Mrs. Jungen, wife of C. W. Jungen, general manager of the Southern Pacific Company, smashing the gold-netted bottle of champagne on the prow, christened the vessel Momus, in honor of the king who holds sway in the city of New Orleans during the annual festivities of the Mardi Gras.

When the Momus was free from the ways, tugs drew it to the wharf, where the engines will be installed, and the interior fittings completed. It will be ready for service about the first of November.

Sunset Magazine

An action of considerable importance to the New Orleans-Havana steamship trade was taken at the recent meeting of the Southeastern Passenger Agents' Bureau, which was held in Chicago. This was the decision upon the rates between this port and Havana for the season beginning Oct. 1, and the admission of a new steamship to the service of the Morgan's Louisiana and Texas Railways of the Southern Pacific System.

News of this action was brought to this city yesterday by Frank E. Batturs, general passenger agent of the Southern Pacific, who attended the meeting as a guest of the bureau. Mr. Batturs says that the steamship to be placed in the service will be the elegant new ship Momus, which is being finished at the Cramp ship yards in Philadelphia, having been launched in the Delaware river with appropriate ceremonies July 31st."

Mr. Batturs says that the railroads in the Southeastern Passenger Bureau will do all in their power to stimulate the Cuban winter travel, so that it is expected that the installation of the handsome steamer to the Havana service will be just about adequate to fulfill the demands of the tourist public.

The Momus will undoubtedly be the finest boat ever placed in the Havana service.

The Times-Democrat, 11 September 1906

The performance of the Creole will be watched with more than ordinary interest by engineers, as it will be demonstration of Admiral Bowles' pet scheme of propulsion. So enthusiastic was Admiral Bowles about this type of engine that he submitted plans to build a first-class battleship with Curtis turbine engines when last contracts were advertised by the navy department. The latter, however, discouraged the idea, as the members of the naval board considered the turbine too early in the experimental stage to entrust the success of a battleship to this new type of engine.

The Boston Globe, 14 September 1906.

|

| Creole on the ways. Credit: Schiffbau. |

|

| Creole ready for launching. Credit: Schiffbau. |

What was to be the second sister and second to enter service, Creole's construction attracted the most attention, both public and professional, owing to her groundbreaking turbine propulsion. Indeed, few American ships of the time garnered more publicity at the time for both her builders or owners. Just before her launching, her Curtis turbines were first tested at Quincy on 13 September 1906, the Boston Globe reporting "The first test was a most satisfactory one, the engines making from 60 to 70 revolutions a minutes, which is considered an exceptionally good performance for the first time in use.

Christened by Miss Mary Harriman, daughter of Edward H. Harriman, president of the Southern Pacific Railroad, Creole was sent down the ways at Quincy at 11:26 a.m. on 18 September 1906, "in the presence of a distinguished company of New York and Boston shipping men and a number of naval officers, including Rear Admiral Joseph B. Coghlan, USN, who came from New York." Among those present for the launching were President Harriman, Admiral Bowles, Carl W. Jungen, W.A. Fairburn, Capt. T.P.C. Halsey (who was to command the vessel) and Lts. Saito and Yoshida and Eng. Hashimoto of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

|

| Credit: Sunset. |

A launching stand which had been built around the bow of the ship was gay with bunting and flags and the ship herself carried all the flags she will have when in service. The christening fluid was champagne and the bottle was gaily decorated with tricolored ribbon. One end of the ribbon was fastened to the bow of the ship and the moment Miss Harriman broke the bottle a nimble boy pulled up the ribbon, at the end of which was the meshwork containing the broken bottle. The pieces of the bottle and the ribbon were later presented to Miss Harriman in a handsome box made for the occasion. The Creole was the biggest vessel, except the battleships, to be launched at the Fore River yards, and as the big hull left the ways she was greeted with tugboat whistles and cheers from thousands of workmen and spectators.

Once in the water, a number of tugs gathered around the Creole and brought her around to the fitting-out dock, while the guests adjourned to the mold loft, where luncheon was served.

The Boston Globe, 19 September 1906.

The twin-screw turbine steamer Creole which in design and construction is probably one of the completest and best vessels ever built for passenger and freight service, was successfully launched at the yards of the Fore River Shipbuilding Company at Quincy Point this morning. In the presence of a large crowd of spectators. The yards were closed to all but ticket-holders, but a fine view was possible from the surrounding shores, which were black with people. They cheered lustily as she slid gracefully Into the water.

The special guests, which included President E.H. Harriman of the Southern Pacific Company, for whom the steamer was built, and a number of the officials of the company, came from Boston on a special train, which was taken over the Fore River Company's private road to the works, from Braintree, and landed at the foot of the launching stand.

Hardly had they arrived when preparations were begun and at 11.23 a.m. she began to move down the ways. As she started. Miss Mary Harriman of New York, a daughter of President Harriman, smashed a bottle of champagne over her bow, and in a clear voice said, I christen thee Creole. As the vessel struck the water, many whistles shrieked out a welcome. Immediately after the launch a luncheon was served in the mould loft by the Fore River Company after which the special train conveyed the party back to Boston.

Boston Evening Transcript, 19 September 1906.

|

| Credit: eBay auction photos. |

|

| Credit: Sunset |

Hardly had the party arrived on the platform when preparations were commenced to launch the steamer. This was made manifest by the pounding, as the wedges that lifted the vessel from her keel were driven home.

Then came a shrill whistle and the pounding stopped. To those on the launching stand it seem as though work had stopped. But it had not, for beneath the vessel were scores of men knocking out the shores and keel blocks.

In the meantime Miss Harriman had been presented with a massive bouquet by President Bowles and taken firm hold of the bottom of Mumm's Extra Dry that hung suspect by a rope of red, white and blue ribbon.

Then came another shrill whistle. This was for the men to saw away the soul pieces, the only thing that held the vessel was sliding down the ways. This was the work of but a minute and the big steamship that will run between New York and New Orleans was sliding down the ways.

As she began to move, Miss Harriman hit the steel bow a sharp blow with the bottle and as the sparkling wine ran down the bow said, 'I christen thee, Creole."

It was just 11.26 when the Creole began to move, and a few second later she was riding gracefully in her native element. Tugs made fast to her and she was taken to the fitting out dock.

As the vessel began to move the party on the launching stand clapped their hands, the whistles in the yards and sailing craft in the harbor screeched out their welcome, and the hundreds of workmen in the yards threw up their hats and cheered.

The Quincy Daily Ledger, 19 September 1906.

|

| Creole (left) and the battleship Vermont fitting out at Fore River September 1906. Credit: The New York, Brockton and Boston Canal, 1908. |

The Times-Picayune of 25 September 1906 reported that Southern Pacific "will shortly add three new ships to its already fine fleet. Two of these ships will ply in the passenger and freight trade between here and New York, and the third ship will run between this point and Havana. All of these ships will represent great improvement over the fine ships now in service. They will not only be larger in every respect as well as more up-to-date and luxuriously appointed, but will be able to accommodate a very much larger number of passenger, both in the cabin and the steerage. The passenger business with New York has increased so much in recent years that the ships already in service, although large, cannot provide for the traffic. With the addition of two such ships as the Creole and the Momus, now building and already launched, it will not only be possible to carry more passengers, but to accord more frequent sailings." It was added that Momus would enter service around 1 December.

It was reported on 1 October 1906 that Southern Pacific, in cooperation with the Atlantic De Forest Wireless Co., would install wireless on Momus, Antilles and Creole.

|

| Momus fitting out at Cramp's. Credit: American Marine Engineer, January 1907. |

Curiously, given the recent announcement of a substantial upgrading of the New Orleans-Havana run, it was reported on 5 October 1906 that effective immediately, Chalmette would be taken off the route and put on the New York service, canceling her sailing the next day. This was owing to "the tremendous falling off in passenger and freight business out of this port because of the troubles in Cuba, which has amounted to nearly one-third of the former business of late." (Times-Democrat, 5 October 1906). It was speculated that the service would not be resumed until Momus went on the route as still planned.

In mid October 1906, Southern Pacific announced that in time for the new ships, the Sunset Limited would be through run from San Francisco to New Orleans starting 16 December with a two day 19-hour run from Los Angeles and two trains a day, one departing San Francisco at 8:00 p.m. and another at 5:00 p.m.

Southern Pacific made it official on 29 October 1906 with the announcement that Momus would, after a roundtrip to New Orleans commencing on or about 28 November, would be placed on the Havana run with the hope she might be able to sail on 22 December to take a large party of school teachers to the Cuban capital over the Christmas holiday. She would replace the chartered Prince Arthur which was returned to her owners early that summer.

On 2 November 1906 it was announced Momus would be handed over to Southern Pacific at New York, and as per the terms of her building contract, undertake a roundtrip to New Orleans as a trial trip. Two days later, the Houston Chronicle reported that with the addition of Momus, Southern Pacific would start an expanded twice a week service between New York and New Orleans with Comus and Proteus in some combination with one of the new steamers.

Coming up from Philadelphia, Momus docked at New York on 24 November 1906, and would remain there for two weeks, "until her equipment of furniture and draperies has been completed," and would sail on her maiden voyage to New Orleans on 12 December. She was opened for public inspection on the 11th.

Momus was delivered to Southern Pacific at New York on 28 November 1906, and according to the Shreveport Journal, "for its trial trip to New Orleans and return. This trip will determine her seaworthiness and whether she will be placed in the service of the company. It is said there is no doubt she will be accepted and that she will be meet all requirements."

"Spick and span, just from the hands of her makers, and fitted with every modern appliance known to make ocean travel pleasant, the steamship Momus, one of the new trio of steamships being built by the Southern Pacific Steamship Company for coastwise travel, will sail out of New Orleans on her maiden voyage to Havana. Thereafter, she and the Excelsior will maintain the Cuban service, the Momus taking the place of the Prince Arthur, which was returned to its owners early this summer." (Houston Chronicle Herald, 26 November 1906).

|

| Credit: The Philadelphia Inquirer, 4 December 1906. |

Dragging a considerable portion of the ways with her, the big ten thousand ton coastwise steamer Antilles, of the Southern Pacific Company Line, was launched yesterday at Cramp's shipyard at 3.30 o'clock yesterday afternoon.

Philadelphia Inquirer, 4 December 1906.

Christened by Mrs. W.A. Fairburn, wife of Southern Pacific's superintending engineer, Antilles was a mite frisky at launching and took much of the ways with her and "gracefully striking the water while river craft and shipyard whistles deafened the air… floated far upstream, and three little tugs shot out after her to tow her back to the dock side." (Philadelphia Inquirer). As it was, the hull started to move as soon as the blocks were loosened: While Mrs. Fairburn was being instructed as to how to break the champagne bottle at the right moment on the boat's prow rebounding hammer blows at the keel blocks told that the Antilles was being loosened, and in a moment would slide down the ways. Hundreds of mechanics and machinists stood on the dock below expectantly waiting and watching for the ship to start. Suddenly the bow seemed to tremble, Mrs. Fairburn raised the wine aloft and crashed the bottle against the moving ship, saying the words: "I christen thee Antilles.." Present for the launch were C.W. Jungens, S.P. general manager, and his wife.

|

| Credit: By Rail or Water, 1906. |

With Antilles launched, all attention reverted back her sister and now finally outfitted with all her interior finery and gleaming in a final coat of fresh paint, Momus was a welcome sight in a sleet storm for those braving the elements to enjoy an afternoon aboard the day before she sailed on her maiden voyage. "Although the day turned out to be a beastly one, " (Times-Democrat), there was a good turn-out (150) of those invited to luncheon and an inspection of Momus between 12:00 p.m.-2:00 p.m. 11 December 1906 alongside Pier 25, North River, hosted by Capt. J.W. Jungen, manager; L.H. Nuttling, general passenger agent; and L.J. Spence, general freight agent.

When Momus cleared Pier 25 on 12 December 1906, two hours off her scheduled time, she had 136 passengers aboard (83 First, 22 Second and 31 steerage). Among those aboard for Momus' maiden voyage south were F.E. Batturs, general passenger agent for the Louisiana lines of Southern Pacific and C.W. Jungen, manager of the Atlantic steamship of the Southern Pacific. Also aboard was Capt. T.C.P. Halsey, formerly commanding Proteus and nominated to command Creole on completion.

The initial trip of the ship from New York to New Orleans was made a notable trip by the management of the company Manager C.W. Jungen of the Southern Pacific Atlantic Steamship lines came down with the ship to watch her during her first voyage” said Mr. Ratcliffe yesterday. “He was accompanied by Captain H.C. Poundstone of the United States Navy who came at Captain Jungen’s invitation to observe the ship during her first voyage and report to him his opinion regarding the vessel. J.W. Powell representing the William Cramp Son's Ship and Engine Building company builders of the ship was also a passenger on the Momus being accompanied by Mrs. Powell and their little son. General Passenger Agent F.E. Batturs, of New Orleans, accompanied by Mrs. Batturs went to New York especially to make the trip down with the Momus.

Detroit Free Press, 23 December 1906.

A wireless sent by F.E. Batturs sent on 14 December 1906 stated: "Momus all that is desired. She is undoubtedly the finest passenger ship that ever entered the port of New Orleans."

Captain Frank Kemble headed a officer and senior staff that included J.F. Scott, Chief Purser; P. Whamond, Chief Steward, Mrs. E. Connor, Chief Stewardess and Mrs. L. Wilkinson, Assistant Stewardess.

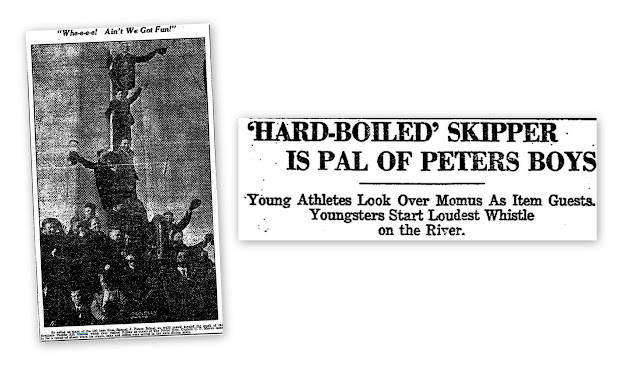

A royal welcome was extended to the new steamship Momus, of the Southern Pacific service, shortly before midnight last night on its arrival in the New Orleans harbor from New York, after finishing its maiden trip in the coastwise service. This consisted in the blowing of the whistle of every craft in the harbor from the great battleship down to the smallest tug, and the simultaneous sounding of the whistles and sirens along the river front. The magnificent new steamship had been delayed in the Gulf since early morning, on account of a heavy fog just outside of the Passes of the Mississippi and could not arrive here in the morning as had been the intention of the company. Late yesterday afternoon a tug was sent down the river to meet it, and with this aid the vessel got to the New Orleans harbor in safety.

Passengers remained aboard the vessel until this morning, with a few exceptions, but those who were seen expressed themselves as delighted with the ship and its accommodation for passengers. The trip was almost uneventful, the vessel making fine time. In many places it exceeded its guaranteed speed of eighteen knots an hour and demonstrated its ability to withstand every test required by the owners, this being the trial trip as well as the maiden trip of the vessel.

The Times-Democrat, 18 December 1906.

An otherwise fast and pleasant first trip south was retarded by heavy fog encountered at the mouth of the Mississippi on the 16th, "the fog banks being so heavy that it was not deemed prudent to venture into the narrow channel." She came into the river at 7:00 a.m. on the following day and expected to dock at 6:00 p.m. The fog persisted, however, and although she worked up to 17.5 knots on the passage up the river once clear, Momus did not get alongside her wharf at the foot of St. Louis St. until 12:15 midnight and those who wished, remained aboard until the following morning.

Capt. Kemble said the trip down "had been a great success and that not passenger was made seasick, so smooth was the sea. The weather was fine and ship had no delays until it reached the passes, where it was held nine hours on account of the fog." (Times-Democrat). Capt. Poundstone told reporters: "The ship was run easily to give her chance to limber up her engines and machinery. The Momus showed her speed coming up the river and proved that she was a very fine ship. On the return trip to New York we will probably run a little faster than schedule time. The Momus is an unusually fine seaboat. There was practically no one seasick during the trip, despite the fact we had several stiff blows." On the trip down, she carried 2,500 tons, half her capacity but would take a full load of cargo to New York.

The magnificent new Southern Pacific steamship Momus, which will hereafter engage in the New Orleans-Havana trade, reached the Southern Pacific wharf at the foot of St. Louis Street last night at 12:15 o'clock, having finished her initial trip from New York to New Orleans. The ship, which is said by marine authorities to be the finest passenger ship that ever entered the port of New Orleans, will load about 4,000 tons of cargo for New York, and then return to New Orleans before entering the New Orleans-Havana trade.

The Daily Picayune, 18 December 1906.

A formal lunch and inspection for 75 invited ticket agents of the Southern Pacific, Union Pacific and Illinois Central was held aboard starting at noon on 18 December 1906, hosted by C.W. Jungen, manager of Atlantic Steamship Lines, and F.A. Batturs, general passenger manager, in the First Class dining saloon. "C.W. Jungen acted as toastmaster and handled his duties in a masterly manner, making the occasion one which will long remain pleasant in the memories of those who were honored with invitations." (The Times-Democrat, 19 December 1906). During the tour afterwards, "it was the consensus of opinion that the Momus was the equal of any ocean liner in accommodations and capacity."

During Momus' maiden call, it was announced that she would hold down the Havana run singlehanded starting on 5 January 1907 with the decision to convert Excelsior back into a cargo ship only and put her on the New York to Galveston run. Momus sailed for New York 21 December 1906 at noon.

The Southern Pacific Company is preparing for the handling of a double weekly service from New Orleans to New York, to begin as soon as the quarantine for Cuban ports is placed upon the Havana steamers. This statement was made yesterday by F. E. Batturs, general passenger agent for the New Orleans-Havana line, by authority of C.W. Jungen, manager of the Atlantic steamship lines of the company, who is here from New York. Mr. Batturs stated that there would be sailings every Wednesday and Saturday from New York and New Orleans in the coastwise service between those points. and that in addition there would be three freight vessels.

The passenger steamers will, in all probability, be the Momus, Comus and Creole, the Momus being taken off the Havana service about the first of April, at the close of the Havana tourist season. The Creole, which is now in process of construction, will be placed in commission also about that time and the Antilles, which will be finished within few months after the completion of the Creole, will come to this port, probably for the opening of the Havana tourist business for the season of 1908.

The coastwise business between New Orleans and New York has increased largely during the past two years and it will be necessary to have semi-weekly sailings in order to accommodate the business. It is planned to bring patronage for the double weekly service a large from Texas points next year, and special rates will be made for the sea trip to New York from New Orleans. Arrangements will also be made with Mexican lines whereby passengers can escape the smoky, hot trip through the East by rail in the summer months.

The Times-Democrat, 20 December 1906.

|

| Credit: The Inter Ocean, 27 December 1906. |

In anticipation of Momus' maiden sailing to Havana from New Orleans and regularly thereafter, the Illinois Central Railroad inaugurated the Special Cuba Flyer, which would henceforth leave Chicago every Friday to connect at New Orleans the follow day with Momus' direct service to Havana, sailing at 1:00 p.m.. The first departure was on 14 January 1907.

|

| Momus, flying the Cramp's houseflag from her mainmast, on departure from the shipyard for trials. Credit: U.S. Navy History Center. |

They are deep-sea vessels of unusual strength, and their excellent arranged passenger accommodation, roomy cargo holds, high speed and beautiful models make them the peer of all coasting vessels.

The Times Herald, 14 November 1906.

A veritable Yankee Trio, Momus, Antilles and Creole were part of that remarkable but comparatively rare threesome of American liners-- Sierra, Ventura and Sonoma; California, Virginia and Pennsylvania; and Mariposa, Monterey and Lurline-- that ranked as among the longest lived and most successful of all passenger ships under the Stars & Stripes. The Southern Pacific threesome remain notable in being the largest trio ever built for the American coastal service and not exceeded individually until Bienville of 1925 and Dixie of 1928. While Creole attracted the most attention with her pioneering yet unsuccessful turbines and equally novel and entirely satisfactory watertube boilers, all three introduced trans-Atlantic liner qualities of strength and seakeeping to the coastal service. They remain among the most handsome and impressive of all liners trading on the Atlantic seaboard.

|

| The splendid-looking Momus, as photographed on 20 September 1907 by Nathaniel L. Stebbins. Credit: historicnewengland |

W.A. Fairburn, the man who designed the new ships for the Southern Pacific Steamship Company, is in New Orleans. He says that the Momus is without doubt one of the most economical fuel boats afloat to-day, and not only is she speedy, but she handles well, and he predicts she will smash a few record before many years.

'All the other boats recently built by the Southern Pacific Company will be just as serviceable,' he continued, 'and I tell you the people of New Orleans have every reason to feel proud of the excellent service given them between here and New York.'

Mr. Fairburn has been connected with the Southern Pacific for several years, and many of the modern improvements recently installed on the ships of the company has been due to his personal ideas.

The New Orleans Item, 10 January 1907.

Momus, Antilles and Creole were the creations of William A. Fairburn (1876-1947), one of a remarkable group of naval architects (among them Ernest Rigg and George F. Sharp) who were born and studied naval architecture in Britain and went on to settle in America and contribute materially to the national genius of naval design, construction and innovation evidenced in the first half of the 20th century. Fairburn emigrated to the United States in May 1891 aboard Servia but returned to Britain in 1896 to attend the University of Glasgow to study naval architecture. Wasting little time in applying his education, he was employed by the Bath Iron Works as chief draughtsman and designed the first all-steel freighter in America when he was not yet 25. By 1900, Fairburn was an independent consultant and worked with the progenitors of the Babcock & Wilcox company and authored several papers advocating the use of the new watertube boilers the firm had developed. He also authored a wide range of books on sociology in the work place. His lasting creation was the non poisonous match for which he was awarded the American Museum of Safety gold medal in 1914 and went on to become president of the Diamond Match Co. where he started work in 1909.

|

| Fairburn's immense Minnesota (shown above at Seattle) and Dakota were twice the size of any American liner on completion in 1904-05. Credit: eBay auction photo. |

Fairburn's most notable ships prior to the Southern Pacific trio were the epic Dakota and Minnesota of 1904-05, built by the Eastern Shipbuilding Company of Groton, Connecticut, for James P. Hill's Great Northern Steamship Co.'s Seattle-Yokohama service. At 622 ft. by 73 ft., and 20,718 grt, they were twice as large as any American-built ship and only Celtic and Cedric exceeded them in size. Ordered in early 1900 and laid down in September of that year, they took forever to build owing to the inexperience of the yard and meddling in the design and engineering features by Hill. As completed, they were underpowered, slow and cumbersome to handle. In any event, they were the most impressive American liners of the new century.

|

| Credit: The Mariners Museum. |

The general requirement of the service have been most carefully and intelligently studies by General Manager Carl Jungen, superintendent of the company, and the finished product clearly shows the result of the carefully thought-out plans that have been carried out in every detail by the builders.

Arkansas Democrat, 25 November 1906.

All three vessels are of the same dimensions and displacement so that the result obtained in economy of fuel, speed development and economy of maintenance will throw much light upon the vexed question of turbines versus reciprocating engines.

The general features incorporated in the design are: First, large freight carrying capacity, with most complete facilities for the rapid handling of cargo; second, passenger arrangement and accommodation having in the view the greatest comfort for passengers travelling from a comparatively cool to a subtropical climate.

The Lincoln Star, 25 November 1906.

The Momus is a steel full-powered ocean-going passenger and cargo vessel of a type that has never before been equaled for coastwise service. She is a deep-sea vessel of unusual strength capable of navigating any waters of the globe and her comfortable sea-going qualities excellently arranged and airy passenger accommodations, large roomy cargo holds, high speed and beautiful model make her the undisputed peer of all coasting vessels.

The Times Herald, 14 November 1906.

|

| Antilles. Credit: U.S. National Archives. |

Imposing in dimension, record setting in size, breaking new ground in machinery (Creole) and marking a new era in American coastwise passenger cargo ships, Momus, Antilles and Creole were first and foremost ships of character, handsome appearance and graceful proportions, ranking as three of the most pleasing of all American liners of their era. Their magnificent funnels, stouter and more modern in profile than their contemporaries and innovative derrick type masts, lifeboats carried above the deck and neat arrangement of ventilators and deck equipment gave them a contemporary, up-to-date appearance. Indeed, their later, taller and more slender funnels made Momus and Creole look older when their age had caught up with them. They were good seaboats with high freeboard, dry and stable and immensely strong, indeed few three ships weathered more severe tropical storms and hurricanes and came through them with flying colors.

|

| Creole on trials. Credit: MIT Museums. |

Previous Morgan Line ships had been built on a light and graceful pattern, in particular the new generation of "El" class freighters designed by Horace See of Cramp's while the Cromwell Line passenger vessels followed a similar model with minimal superstructures and narrow proportions and considerable sheer.

|

| Splendid photo of Antilles outbound from New York, New Orleans-bound. Credit: Mariners' Museum. |

With Momus, Antilles and Creole, W.A. Fairburn broke new ground for Morgan Line steamers while borrowing some of the imposing elements and enormous capacity of his Minnesota pair to produce coastal passenger and cargo vessels that were truly North Atlantic liner in qualities and capabilities. As such, they were ideally suited to a route, comprising some 1,800 miles one-way that combined, seasonally the extremes of north and south as well as the rigors of Cape Hatteras in winter and the Florida coast in late summer and early autumn with some of the worst tropical storms and hurricanes that were often the lot of Morgan Line ships. Additionally, the new ships offered double the passenger and cargo space of the earlier Comus and Proteus.

All these considerations and market requirements produced a trio of significant ships with impressive dimensions: 440 feet (length o.a.), 420 feet (b.p.), 53 feet (beam), 37 feet (load draft) and gross tonnages of 6,878 (Momus and Antilles) and 6,754 (Creole) which made them quite the largest of all American coastal vessels at the time and still the biggest trio of such ships ever built. Even the majestic Brazos of rival Mallory Lines which entered service in 1908 was, at 6,399 grt, 401 ft. by 54 ft., not nearly as large. By way of comparison, the first of the trio of Russian American Liners, Czar of 1912 was 6,345 grt, 425 ft. by 53 ft.

|

| Creole hull cross section. (For full-size scan, LEFT CLICK on image) Credit: International Marine Engineering, October 1906. |

The hull has been specially designed to provide against the weaknesses inherent in hurricane deck vessels have large cargo ports in wake of the over-all hatches on hurricane deck. The provision for extra strength consists in constructing the deck mentioned as the strength deck for about one-half the length amidships, and at the ends of the superstructure it is continued down to main deck by specially designed hogging girders, and from thence forward and aft the main deck is treated as the strength member. It will be obvious that this provides the structure with immense strength as compared with existing hurricane deck vessels.

On superstructure the midship houses are of comparatively light construction, specially braced to take the racking stresses incident to their location on ship. In addition, expansion joints are fitted at forward and after ends of superstructure, to relieve these erections of undue stresses.

The subdivision of the vessel mentioned arranges for four cargo holds in addition to orlop, lower and main 'tween decks, the lower and main 'tween decks being pierced with large hinged cargo ports providing for the expeditious handling of cargo, in addition to which there are four especially large over-all hatches extending the full width of hurricane deck, giving roomy exits for handling freight.

International Marine Engineering, October 1906.

|

| Creole mid hull and superstructure cross section. (For full-size scan, LEFT CLICK on image. )Credit: International Maritime Engineering, October 1906. |

Laid out on the "hurricane deck type" model, each had three complete decks extending fore and aft: Upper, Main and Lower, with a two deck-high superstructure: Promenade and Saloon with a separate bridge and wheelhouse island and aft poop deck house. All of the accommodation, for both passengers and crew, was in the superstructure or first hull deck (Upper) to afford maximum ventilation and all passenger cabins (First and Second) were outside with the idea that "the ports can be kept open in all but the roughest weather." The hull was given over to cargo carriage and of immensely strong construction with girders and pillars internally instead of the usual closely space small stanchions of coastal vessels. Conversely, the large superstructure was of "particularly light character and expansion joints are fitted to relieve such light structure from injurious stresses." (American Marine Engineer). A double bottom extended for three-quarters of the length of the hull amidships fitted for the storage of fresh water as well as water ballast if needed. In all, and including tanks, the hull was divided into twenty-two water-tight compartments.

At the base of each mast was a substantial steel quarter house, the forward one containing house four steam winches and also fitted up as wash room and toilet for steerage passengers, and the after one as seamen's quarters, mess room, wash places, etc., in addition to enclosing four cargo winches.

With a total cargo capacity of 335,000 cubic feet, these ships had about 100,000 cubic feet more capacity than any coastal vessel of their time. Of this, 5,000 cu. ft. (equal to four railroad reefer cars) was refrigerated to 36 degs. and additional chilled storage provided for provisions.

While it was common for American coastal ships to use side ports in the hull to directly access the 'tween decks, especially for package freight, these ships were again more Atlantic liner with four conventional holds, two forward and two aft, with hatches extending right across to the sides with hinged watertight steel covers, in addition to large side ports, four sideports to the upper 'tween decks and eight to the lower 'tween decks. Unusual to these ships, especially for the time, was their main cargo handling gear which was by means of substantial cargo booms hung from heavy derrick posts, fore and aft, with sheer and taper to suggest masts and with tops mainly to carry the wireless antenna and with no conventional rigging or ratlines. The holds were worked by sixteen 7½-ton derricks and one 20-ton derrick operated by eight double drum steam winches

In addition to cargo, each ship could bunker 1,700 tons of coal and the water tanks contained 800 tons of water.

The machinery and boilers were designed by W.A. Fairburn, the chief engineer of the line, and were constructed in all their details, with the exception of special auxiliaries, by the Cramp company in accordance with Mr. Fairburn's directions. The auxiliaries were also specified by Mr. Fairburn and to him belongs the credit of this magnificent specimen of marine engineering.

The American Marine Engineer, January 1907.

The machinery of Momus and Antilles, identical and conventional, attracted far less attention (in every way) than Creole's novel and troublesome turbines.

|

| Momus' engine in the shop at Cramp's. Credit: Cramp's Shipyard, 1910. |

Momus and Antilles each had one vertical three-cylinder triple-expansion engine, direct acting with a high pressure cylinder (34" dia.) forward, low press cylinder (104" dia.) in the middle and an intermedate cylinder (57" dia.) aft with a common stroke of 63". Steam was generated by three double-ended (15' 4" diameter by 21' 4" long) and four single-ended boilers (15' 4" diameter by 11' 2" long), the former being the largest boilers yet built in an American yard, each with eight furnaces each. The total grate surface was 770 sq . ft ., the heating surface was 26,500 sq . ft. The engine could develop about 7,000 h.p. when making 70 r.p.m. with a steam pressure of 234 pounds at the boilers.

|

| One of Momus' boilers. Credit: American Marine Engineer, January 1907. |

The single propeller was of the built-up type, with a cast steel hub and manganese bronze blades, 20' in diameter and with 26' 6" pitch. The blades were fitted into recesses in the hub and held in place by steel bolts, kept from turning by lock nuts.

The ship has been designed for a sea speed of sixteen knots per hour or about eighteen and one-half statute miles which speed is higher than that maintained by any vessel engaged today in American coastwise service.

Detroit Free Press, 23 December 1906.

The magnificent original funnels of these ships were doubled with the inner one 12 ft. 6 in. diameter venting the furnaces and an outer funnel casing 15 ft. 6 in. diameter created a interior ventilation flue to the boiler room. The funnel itself rose 110 ft. from the grates.

All three vessels are of the same dimensions and displacement so that the result obtained in economy of fuel, speed development and economy of maintenance will throw much light upon the vexed question of turbines versus reciprocating engine.

The Lincoln Star, 25 November 1906.

Contrary to the views of many thoughtful naval engineers, and probably in opposition to the advice of the several inventors, turbines were installed in vessels which were not designed to be operated at continuous high speed. The installation of Curtis turbines in the yacht Revolution and in the Morgan Line Steamer Creole are examples of the keen desire that existed upon the part of individuals to discard the reciprocating design, even though the development of the turbine had not progressed to a point to warrant its installation in vessels operating under such moderate speed.

Engineers and Engineering, 1912.

Patented in 1894 by Charles Parsons and first used by a vessel in 1897, the marine turbine was the last great wonder of the Victorian Age. Its promise, if greater than its ultimate practical application before the developed of gear reduction for a system that was literally too fast and efficient to be economically transmitted to screws in ships below a certain speed and size, redefined the express Atlantic liner and started a global naval arms race with H.M.S. Dreadnaught. It was indeed the last great British marine engineering invention. And in an era of virulent nationalism, prompted varying imitations and supposed improvements by other nations' native engineering abilities.

|

| General Electric brochure, 1904. |

In America, then at the dawn of a century that would propel it into the global technological and economic dominance that Britain had enjoyed in the 19th century, the development an alternative to the Parsons turbine came from Charles Gordon Curtis as early as 1896 and a marine version of what had been primarily used for electric generation, was developed by 1901 after patent had been acquired by General Electric Co..

The first use of the Curtis marine turbine was in the yacht Revolution in 1902, a two-stage 1,800 i.h.p., 672 r.p.m. installation, whose performance was deemed by the Board of Naval Engineers as "quite satisfactory" while being "rather in the nature of experimental appliances." From this, both Southern Pacific and the U.S. Navy specified Curtis turbines in Creole and the cruisers Salem and Birmingham in 1905.

|

| Longitudinal Section of Curtis turbine on Creole. Credit: Engineer, October 1907. |

|

| Curtis Marine Turbine as fitted with Creole. Credit: Steam Turbines by Thomas Clapp. |

Creole was intended to be an exemplar of American engineering genius and manufacturing prowess as the first Yankee-built twin-screw turbine steamer and the largest merchantman to date with watertube boilers as well representing the forward thinking Southern Pacific under Harriman's dynamic management. Not one to shy from new technology, but hedging his bets, Harriman stipulated that the contract require a 16.7-knot speed over the measured mile and a 16-knot average on 6½ tons of coal on a roundtrip between New York and New Orleans. It was, indeed, that same requirement that Momus and Antilles satisfied and the turbine experiment confined to but one of the three ships.

|

| Original caption: The assembled rotor of one of the propelling turbines with diaphragms in place. Credit: International Marine Engineering, October 1906. |

|

| Original caption: Wheels ready for assembling on shaft. Turbine casing at the right. Credit: International Marine Engineering, October 1906. |

|

| Original caption: The outside of the turbine casing, and six disks of blades on the rotors. Credit: International Marine Engineering, October 1906. |

The main propulsion machinery of Creole consisted of two 10-foot reversing Curtis turbines, driving twin screws. Each turbine had a rate capacity of 4,000 b.h.p. at 230 r.p.m. and operating at 250 p.s.i., 100 degs F. Unique to the Curtis design, there was no separate astern turbine and each unit had seven ahead wheels and two reverse wheels.

|

| Creole engine room looking aft. Credit: Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers |

The turbine consists of a cast-iron cylindrical casing divided by dished cast-iron diaphragms into series of separate compartments (cast steel is used for the two first stages, for strength). In each compartment or stage" there is a separate wheel, which carries on its periphery three rows of moving buckets (for reasons later described the first wheel has four rows). The wheels are all mounted on a hollow steel shaft carried by self-aligning bearings, as shown. Where the shaft passes through the diaphragms they are provided with bronze bushings having a small clearance, thus preventing appreciable steam leakage from one stage to the other. Where the shaft passes out through the ends of the casing it is provided with carbon stuffing-boxes, which prevent steam leaking out at the ahead end, or air leaking in at the back end, where a vacuum exists.

The stuffing-boxes are supplied with steam in the space between the carbon packing to prevent air leaking in and lowering the vacuum. They are also drained to the fourth stage shell.

Cast-steel steam-chests for ahead and astern running are attached to the front and back casing-heads as shown, and are flanged for the main steam-pipes. The nozzles for each stage are bolted to the diaphragms as shown, the diaphragms having steam-port openings cast in them to allow the steam to pass through to the nozzles.

Manoeuvring is accomplished by means of two lever-operated balanced throttle valves, each taking steam from the main steam-pipe, one delivering to the ahead steam-chest, and the other to the astern steam chest.

There are seven ahead wheels and two reverse wheels. The reverse wheels are mounted on the after end of the casing, and under ordinary ahead running they are in a vacuum, and therefore do not waste power by steam friction. They are the same as the ahead wheels, except the blades are reversed. To reverse when going ahead, the ahead throttle-valve is shut and the reverse throttle-valve is opened, which is easily and quickly accomplished by the operating levers of the two throttle-valves.

International Marine Engineering, October 1906.

|

| Original caption: Plan of the hold, showing arrangement of the ten Babcock & Wilcox boilers and two Curtis propelling turbines and shafting. Credit: International Marine Engineering, October 1906. |

The early Curtis marine turbine, alas, was not a success and in particular the earlier versions as installed in Creole and the light cruiser Salem, for reasons outlined in 1917:

The Curtis turbine is of the type known as "impulse velocity compounded." It had been used quite extensively on shore for driving electric generators before the marine type was designed. The type used on shore being built as vertical units, it became necessary to depart from this form to adapt the turbine for use on board ship.

At this early date the theory of this turbine carried with it the idea that as all expansion of the steam took place in the steam nozzles, wherein steam pressure was changed into velocity, there was no change in pressure throughout the blades of any one stage, and that therefore there was no unbalanced steam thrust on the rotor of the turbine.

The turbines of the Creole and Salem were made practically from the same patterns, the nozzle areas of the Salem being, however, twice as great as those of the Creole on account of being called upon to deliver twice the power. The turbines were built with seven-wheel stages, the drum type of Curtis turbine not having yet appeared upon the scene.

The turbines of both of these vessels were fitted with a type of blading which "hind sight" has taught us was so weak as to be a serious menace to the reliability. The diaphragms between stages were made each in one piece, and to overhaul the shaft packing of any diaphragm required that the turbine shaft be completely stripped up to and including the desired diaphragm. Further, the thrust bearings were made completely independent of the turbine casings, which was a serious mistake, as these bearings should come and go with the turbine as it expands or contracts.

Attention is called to the fact that while the total steam consumption with reciprocating engines is decidedly better below about 22 knots than that of either the Curtis or the Parsons turbines, even though the latter are fitted with cruising turbines which are in use from 20 knots down, the economies are about even at 22 knots, and above that speed both types of turbines have a decided superiority. Hence, in cases where high speed and light weight were the prime factors to consider in the design of machinery for a vessel, some type of turbine machinery' was always to be preferred over reciprocating engines. In cases where the speed of vessel was comparatively low, where high speed was seldom called for and where economy of propulsion at cruising speeds was of paramount value, the reciprocating engine was, under the conditions of turbine design existing at this early date, very much to be preferred.

Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers, May 1917.

|

| Original caption: Babcock & Wilcox boilers installed on ship, showing superheaters, boiler casing not yet fitted. Credit: International Marine Engineering, October 1906. |

Although her turbines garnered the most attention, Creole's steam plant was almost as noteworthy and up-to-date consisting of ten of the latest Babcock & Wilcox watertube boilers with superheaters. This type of boiler had only recently been introduced and first used in James C. Wallace on the Great Lakes, realizing a 9 per cent savings in coal consumption, and followed by an order by the U.S. Navy to reboiler the battleship Indiana. The use of superheated watertube boilers was championed by W.A. Fairburn in a number of papers and it was his inspiration to fit them to Creole, making her the first big American merchantman so equipped.

In all, ten Babcock & Wilcox watertube boilers were installed, each with superheaters, designed to work under 250 psi and 100 degs. F. superheat. The furnaces had a total grate surface of 770 sq. ft. and a heating surface of 28,500 sq. ft. with 4,450 st. ft. superheated.

|

| Screwed. Creole's original and wholly unsatisfactory adjustable four-bladed propellers. Credit: Schiffbau. |

Possibly no other significant passenger vessel ever went through more pairs and variation of propellers than did Creole during the first two years of her life. If the Curtis turbine installation in itself was flawed in design and unsatisfactory in operation, economy and speed, much of the blame for her disappointing performance was laid at faulty screws, although having gone through five or six sets, it was clear the screws were merely adding to the problem not the real cause of Creole's dismal performance as a turbine steamer. That being said, many early turbine liners, notably Lusitania and Mauretania went through several changes of screws and it was sometime before propeller design caught up with harnessing the power of high-speed direct-drive turbines.

As delivered, Creole was fitted with twin propellers, 11 ft. 6 in. in diameter with steel cast hubs and four adjustable manganese blades which was said to be designed by the U.S. Navy and tested in the experimental tank at Washington Navy Yard. These proved totally unsatisfactory on the ship's first trials and were replaced by fixed three-blade screws, 10 ft. 9 in. in diameter with 8 ft. 2 in. pitch which was less than the originals. With these Creole was able average 16.71 knots on a four-hour full-speed trial and that was sufficient to partly satisfy her contract requirements and she proceeded to New York to undertake her real test, a roundtrip to New York under full load conditions and normal running. Even so, it was admitted that "the propulsive efficiency obtained by the propeller used is very poor, although it is better than that obtained by the first propeller fitted to the vessel. A third design is now being built, and it is expected that a material improvement will be obtain, which, of course, will give a higher speed of the vessel for the same brake horsepower of the turbine." (Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers, August 1907).

|

| Creole leaving Fore River on one of her initial trials. Credit: Mariners' Museum. |

A four-hour full-speed trial was run between Wood End Light to Boston Light and return on 19 June 1907 recording an average speed of 16.83 knots out and 16.6 knots back or 16.71 overall .

The maiden voyage recorded a disappointing average of 13.5 knots southbound and 14 knots for the roundtrip and failing her contract requirements as to average speed and fuel consumption on a regular return voyage.

As will be recounted, Creole spent two months back at Fore River and went through two more sets of screws and two more unsuccessful trials. In November a third set of trials, she averaged 17.75 knots on yet another set of screws and made a satisfactory trial run to New Orleans and back.

Back in service January 1908 but by July, Creole had continued to demonstrate an astonishing appetite for coal and in a last effort to make her good, was back at Fore River to be get yet another new set of propellers and be fitted with forced draught. Back in service in November, she proved no less satisfactory, burning 2,000 tons a roundtrip compared to the reciprocating engined Momus and Antilles' 1,000-1,200 tons, and simply so uneconomic to run that she was laid from late late January 1909.

E.H. Harriman, who died on 9 September 1909 of stomach cancer, aged only 61, would never realize his ambitions with Creole and shortly before his death, Southern Pacific decided to put an end to the endless cycle of tweaks, changes and screws, and remove her turbines entirely and replace them with conventional triple-expansion engines along the lines of Momus and Antilles, but retaining the twin-screw arrangement and, significantly, the watertube boilers. As relations between Fore River Shipyard and Southern Pacific were increasingly strained during the endless issues surrounding Creole's performance, yard intimating her problems stemmed more from her boilers, inept firing and poor coal, yet when Southern Pacific elected to proceed with the re-engining out of pocket pending claims against the builders, it was decided to retain the original boilers which, as it proved, were wholly satisfactory and more economical than the conventional Scotch boilers in her sisters.

The reports regarding the ship have been numerous and varied, but this much is certain, that she has not fulfilled her contract requirements as to speed and fuel consumption. It is altogether probable that the Creole's troubles are in a great measure those referred to elsewhere in this issue, as, common to turbine-driven ships. In all probability, the difference in combined efficiency of engine and propeller as between the reciprocating engines and turbines, was either overlooked or not sufficiently considered. It is not to be considered for a moment that this will in any sense affect the standing of the Curtis turbine as a marine motor within those limits where the turbine may be properly and profitably employed. The designed speed of the Creole, which is stated to be 16 knots, is in itself too slow for the best results; in fact , it is doubtful if any design of turbine or propeller can make so good a showing at this speed as the reciprocating engine. Moreover, the Creole was the first installation of the Curtis marine turbine, which has installed since been the scout cruiser Salem, and is being installed in the battleship North Dakota. The Salem did not make quite so good a showing as the Chester, which is fitted with Parsons turbines, but it was later discovered that the blading in the Salem had met with serious injury , and it is too soon to say that the results obtained are to be considered final.

The Marine Review, June 1909.

Creole was sent to Cramp's and had her turbines removed and replaced by reciprocating machinery which, if it were not for the astonishing improvement in her performance, would be regarded as a retrograde development. Instead, it redeemed the vessel. Her new machinery consisted of two triple-expansion engines with cylinders of 27¾ ins., 36½ ins. and 79 ins. in diameter with a 42 in. stroke, developing a total of over 8,000 s.h.p., "carefully designed so as to divide the fall in temperature as nearly as possible equally among the three cylinders, and also to make the bearing pressures as nearly as equal as possible." (American Marine Engineer, September 1910).

This vessel a few years ago was very prominently in the eye of the shipping world on account of her machinery equipment, which consisted of Curtis turbines, with Babcock & Wilcox boilers, both representing a departure from the ordinary practice, although as our readers well know, a large number of vessels on the Lakes and on both coasts have been fitted with these boilers. The real novelty was the Curtis Turbines.

It was a matter of surprise to those who were familiar with the conditions for efficient use of the turbine, that the manufacturers of the Curtis Turbine were willing to make an installation where the conditions were such as to make success very doubtful. Mr. Parsons has gone on record as opposing the use of direct-connected turbines where the speed of the ship is below 18 knots, but apparently the Curtis people had more courage. We have nothing to say regarding the use of turbines in places where they will give good results, and we only make this mention here to make the story of the Creole complete.

It is well known that while the vessel was fitted with turbines she was never satisfactory. She did not maintain her schedule, and she used an enormous amount of coal. After repeated trials, and considerable contention between the owners of the boat and the builders, the former finally decided to remove the turbines and install triple expansion engines, to work with 210 lbs. pressure and 50 degs. Of superheat.

There had been statements to the effect that the trouble was not due entirely to the turbines, but in part to the water tube boilers, and the allegation was made that the engineers of the merchant service and their men were not equal to the job of handling these boilers. However, the owners decided to keep the boilers, so that the excellent performances which will be mentioned in a moment have been been made with the very same boilers which were in use when the turbines were in the ship.

After the new engines had been installed and given a short dock trial, the Creole was brought around from Philadelphia to New York on May 14th and 15th, this being their first trial in free route. Everything worked nicely and advantage was taken of passing the measured mile at the Delaware breakwater, to standardize the screws and determine her speed. Under natural draft, and without any forcing, an average in a number of runs over the measured mile gave a speed of 16.4 knots.

The trip to New York was a complete success in every way, and it was decided to place the Creole on the line for regular service. On her first trip, beginning May 25th, all the boilers were used with the idea of seeing just what she could do in the way of a performance under full power. It should be stated here that there are fans in the uptake to assist the draft, but these were not used on this trip, and indeed it was found that under natural draft alone the boilers would furnish more steam than the engines could work off, so that the ash pit doors were up a good portion of the time. The engines were worked with the links in full gear, and also with the by-passes to the I. P. and L. P. cylinders.

The result of this first trip was highly gratifying to the owners and to all concerned, and the schedule was beaten by several hours, both on the southern and northern trips, about 6 hours going south and 16 coming north. It was remarked by men who are well and favorably known in marine circles, that with the machinery as now fitted the Creole was the most satisfactory ship they had ever had the pleasure to observe, owing to the fact that the volume of steam was as easily obtained on the fifth and last day of the trip as on the first; nor did the warmer weather in southern waters have any effect on the ability to make steam. The fire-room temperature was also favorably commented upon as it did not exceed 100° in the warmest weather.

On the next round trip, it having been found that 10 boilers gave more steam than was needed, the ship was operated with 9 boilers going south and 8 boilers going north. The schedule was maintained without difficulty and again it was found that it was constantly necessary to close the ash pit doors. As a result of this experience, it was decided on the next trip to use 8 boilers going south and 7 boilers coming north. This trip was also a complete success in every way, so that it was decided on the next trip to again reduce the number of boilers in use. Beginning with this next trip, and continuing up to date, 7 boilers are used for the southern trip and 5 for the northern. If there had ever been any question as to the ability of the boilers to supply ample steam for driving the ship, these repeated trips in regular service have entirely settled the matter.

It will also be very interesting to know something about the coal consumption and without going into great detail, it may be said that since the adoption of seven boilers for the down trip and six for the up trip, the entire coal consumption on the Creole for the round-trip, including port charges, is only about 1,100 tons. This is less than she used for the southern trip alone when the old machinery was in use. It is also interesting to know that the machinery shows a decided saving in coal over the sister ships, Momus and Antilles, amounting to some 10 or 15 per cent. This is doubtless due in part to the higher steam pressure carried and the use of superheated steam, as well as the greater economy in evaporation of the water tube boilers as compared with the Scotch.

It was noted above that there had been remarks by those who were not qualified to judge, that the engineers in the merchant service and their men could not properly operate water tube boilers. When the vessel first came out the turbines made such an enormous demand on the boilers for steam that the firemen were compelled to work themselves almost to death, with the result that the ship was very unpopular among the men. With the new machinery and the boilers worked as they should be, the fireman's job has become a decent one, with the result that the ship has become very popular among the firemen, who stick by the ship and are very attentive to their duties-presumably being desirous of giving satisfaction in order to retain their jobs. It is easy to understand why these boilers. should be popular with the firemen, because steam can be raised rapidly owing to the much smaller amount of water contained than in the Scotch boiler, and for the same reason it cools off rapidly. There are no hot back connections to be cleaned out, and when washing out the boilers it is not necessary to climb on the braces or curl in the bottom manhole and wallow in several inches of water. It has been remarked that on the Creole the boilers can be washed out without getting wet. The firemen are recruited from the same source as before the change.

From the standpoint of the engineer, the rapidity with which steam can be raised and the boilers will cool off, is a great advantage in case any overhauling or repairs are necessary, to say nothing of the saving in the coal required for raising steam. Just on this point of the rapid cooling of the boilers, it was remarked on a recent stay of the ship at New Orleans, which was only for 48 hours, that the Creole's fireroom was the only cool place in New Orleans.

A very important point about the boilers, from the standpoint of the captain and owners, based on the rapidity with which steam can be raised, is the fact that it is not necessary to keep a reserve of boiler power actually under steam. It having been found that 7 boilers are sufficient for the southern trip, under average conditions, if the captain sees that bad weather is approaching he can have an additional boiler connected up in an hour or two. This enables the ship to be run with the utmost economy.