To Dixie's Land

I'm Bound to Travel

Away, Away, Away Down

South in Dixie.

Dixie's Land, Daniel Decatur Emmett, 1859.

When the Dixie was finally floated and towed to New York to be reconditioned, we said that only a ship of the stoutest and soundest construction could have lived through the hurricane, and that for that reason when returned to service to she should become as popular as before. We repeat the prediction.

The Dixie should have a warm welcome when she sails into New Orleans next week. The city is to be congratulated on the fact that she has been recommissioned and the Southern Pacific's fine coastwise service is to be resumed on its former fine scale.

New Orleans States, 12 December 1935.

One of the most popular passenger liners in the country, the Dixie had a meteoric career from the time she was commissioned and placed in the New Orleans and New York service nearly 13 years ago. Her cabins were full on every voyage, her passengers came back for second and third trips.

Sunday Item-Tribune, 23 February 1941.

Discover the Good Ship Dixie and "100 Golden Hours at Sea" that once linked Manhattan with the Mighty Mississippi and united Yankee with Dixie's Land.

s.s. DIXIE 1928-1941

|

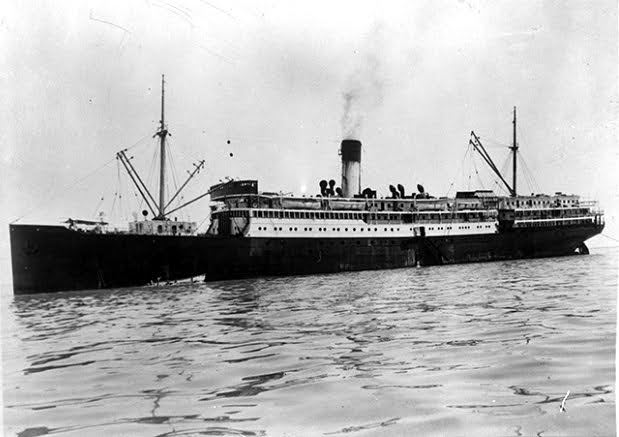

| Dixie outbound in New York, late 1930s. Credit: Roger Scozzafava photograph. |

The Morgan Line has been operating between New York and New Orleans since 1876. In the flight of that long time it has constantly increased in popularity. Many years ago, at the conclusion of a voyage between these ports on one of the Morgan Line steamers, a delighted passenger declared that he had just spent 'one hundred golden hours at sea.' This apt remark became a slogan of the line and it frequently finds it way into letters of commendation written by other equally delighted voyagers.

The last word in the subsequent development of this service has been expressed in the new passenger and freight steamship Dixie. This new ship was built at a cost of nearly two and half million dollars, and the perfect behavior of the vessel from the start has fulfilled the expectations of her builders and owners.

Morgan Line brochure

Dixie was the bookend to a remarkable, transformational life's work of one individual. Rightly called the father of American coastal shipping and credited, too, with originating the entire transportation infrastructure of the Southwest, the story of Charles Morgan (1795-1878) is, in relation to the story of the last vessel with links to him, remote enough to be summarized, more than adequately, by this citation by the Texas State Historical Association:

.png) |

| Charles Morgan, 1795-1878. |

Charles Morgan, shipping and railroad magnate, was born on April 21, 1795, in Killingworth (presently Clinton), Connecticut, the son of George and Betsey Morgan. He moved to New York City at the age of fourteen and soon began a ship chandlery and import business. That venture led to investments in merchant shipping and ironworks and to management of several lines of sailing and steam packets trading with the South and the West Indies. In 1837 Morgan opened the first scheduled steamship line between New Orleans and Galveston. From that axis he expanded his regular service to Matagorda Bay ports in 1848, Brazos Santiago in 1849, Vera Cruz in 1853, Key West in 1856, Rockport, Corpus Christi, and Havana in 1868, and New York in 1875. He was also both partner and rival of Cornelius Vanderbilt in attempts to establish an isthmian transit across Nicaragua in the 1850s.

During the Civil War Morgan's vessels were seized or chartered for military and naval service by both sides, but he profited from wartime charters and machinery contracts and resumed his regular routes in 1866. As before the war the Morgan Lines dominated intra-Gulf trade through excellent service and his possession of exclusive United States mail contracts. Much of Morgan's postwar career was devoted to integrating his water lines with rapidly developing rail carriers in Louisiana and Texas. He was also deeply involved in the interport rivalries of New Orleans, Mobile, Galveston, and Houston.

Among railroads, he organized, reorganized, and managed the New Orleans, Mobile and Texas, the New Orleans, Opelousas and Great Western, the Louisiana Western in Louisiana, the Gulf, Western Texas and Pacific, the Houston and Texas Central, the Texas and New Orleans, and associated lines in Texas. In the 1870s he also built, at his own expense, Houston's first deepwater ship channel to the Gulf. In 1877 he established Morgan's Louisiana and Texas Railroad and Steamship Company as a holding company to control and operate his integrated water and rail services.

The system was absorbed under lease by the Southern Pacific Company between 1883 and 1885. On July 5, 1817, Morgan married Emily Reeves; they had five children. After her death in 1850, he married Mary Jane Sexton on June 24, 1851. He died on May 8, 1878, in New York City.

Texas State Historical Association

One of the last American steamship lines to bear the name of its founder, the Morgan Line was both a tribute and an exemplar of both Charles Morgan and the age in which he lived. It was one of the true pioneers both of American coastwise shipping, and what is now known as "integrated shipping," being linked to Morgan's railroad enterprises, opening up the great American Southwest to the Age of Steam during the astonishing three decades before the Civil War that saw the United States expand both geographically and commercially westwards. The heart of the line lay in the Gulf of Mexico, to which Morgan introduced steam navigation, created most of the port infrastructure of the Texas and furthered that greatest of all southern ports, of river and sea, New Orleans. Here was American enterprise achieved by rail and ship that was bold in concept and determined in execution that as its result, the welding of the South and Southwest to the chain of commerce of the Republic from North River to Mississippi River and into the Gulf of Mexico.

Morgan, in cooperation with business partner James P. Allaire started the first regular coastal steamship service on the Eastern Seaboard of the United States in 1834, between New York and Charleston, S.C., using side-wheel steamers with single-expansion engines. The New York Steam Packet Line commenced operations with the sailing on 1 March of "splendid new steam packet William Gibbons" from New York for Charleston and "the favorite boat," David Brown, from New York on 8 March and maintain weekly sailings. The route, fraught with dangerous navigation and weather hazards, resulted in the litany of shipwrecks (including the loss of Home off Cape Hatteras in October 1837 with the loss of nearly 100 souls) and resulting bad publicity, that forced the withdrawal of the service in 1838.

The line's association with Texas would proved its most enduring and pioneering and introduced the Morgan Line name as well as bringing steam navigation to the Gulf of Mexico. The first voyage credited to Morgan Line was by Columbia, which arrived at New Orleans on November 18, 1837, and made its maiden voyage to Galveston on the 25th. She was soon joined by New York on what quickly became a hugely popular and profitable route. The company secured a mail contract from the U.S. Government in 1845 when Texas joined the Union and went on to earn enormous profits during the ensuing Mexican-American War

I would advise all travellers to beware of Harris' & Morgan's line of Texas packets, for they treated us like dogs.

Very respectfully yours, S.

The Concordia Intelligencer, 7 April 1849

By now, Morgan's shipping interests were centered on the Gulf of Mexico, from New Orleans to Texas. In this, he partnered with Israel C. Harris, his son-in-law, who handled the New Orleans side of what was titled Harris' & Morgan's Line of Texas Packets. In 1849, unwilling to pay high port charges at Lavaca, Morgan built Powderhorn, which grew into Indianola, principal port for the line. and the chief port of the line. In 1858, Harris' & Morgan's maintained three sailings a week from Galveston and two from New Orleans, and by 1860 the company had a monopoly of coastal shipping.

During the ensuing Civil War, 1861-1865, Morgan's ships were seized by the Federals or Confederates and much of the railroad network was ravaged by war and overuse. Yet, Morgan, whose new shipyard enterprises had made enormous profits during the war, stepped in to buy many rail lines in the South at post-war distressed prices, rebuilding and integrating them into his ever expanding network.

When Harris passed away in 1867, another son-in-law, Charles A. Whitney, stepped in to handle Morgan's steamship interests and also his expanding railroad empire, both in the South, and with connecting shipping services, to Mexico and Cuba. In the 1870s pooling agreements were worked out among Morgan's Louisiana and Texas Railroad and Steamship Company, the Louisiana Western Railroad Company, and the Texas and New Orleans Railroad. In the late 1870s Morgan worked with E. W. Cave to make Houston an inland port with better facilities, creating the ship first channel into the port. Morgan had pioneered the progenitor of the modern intermodal cargo shipping concept. Now it was time to extend the links north and reinstate the New Orleans to New York steamship route.

When Mr. Morgan's new steamship line from New York to Brashear was first spoken of, and our merchants were apprehensive that it would affect the cotton and sugar trade of New Orleans, we endeavored to demonstrate the emptiness of such fears. And so far as the great staples are concerned we have had no reason to change our views. The projected line has since become a reality, the pioneer ship sailed on the 21st inst. with some hundreds of tons of freight, and|the enterprise, now fairly inaugurated, will henceforward be prosecuted with the energy, perseverance and consummate ability which are conspicnous in all Mr. Morgan's undertakings.

Times-Picayune, 29 July 1875.

|

| The paddle steamer Hutchinson by Capt. William Lindsay Challoner. Credit: Mariners' Museum. |

The steamer Hutchinson sailed from Brashear (later renamed Morgan City) on 21 July 1875, followed by W.G. Lewis on 1 August. With a depression in 1874, Morgan was now competing on a route already served by Mallory, Cromwell and Merchants & Miners, resulting in protracted rate war. As so often, Morgan won the day, and when Mallory and Merchant Miners abandoned the New York-New Orleans route, Morgan switched its terminal to the Crescent City and Morgan and Cromwell content to share the business between them.

|

| One of the first screw steamers of the line, Morgan City, which ran on the New York-New Orleans route. Painting by Antonio Jacobsen. Credit: eBay auction photo. |

The myriad Morgan enterprises were finally unified corporatively with the formation of Morgan's Louisiana and Texas Railroad and Steamship Company in 1877, but the following year, the great man passed away. His son-in-law, Charles A. Whitney, continued to run the business until his death in October 1882.

Morgan's heirs had neither the desire or ability to continue to run the vast enterprise the patriarch had created and in 1883 the majority of shares in the company were sold to Collis P. Huntington who seamlessly melded the Morgan Line, Louisiana and Texas Railroad and Steamship Co. into his Southern Pacific transcontinental railroad which reached El Paso, Texas from California in 1880 and extended to New Orleans in 1883. The first S.P. train from New Orleans reached San Antonio on 6 February and from San Francisco on the 7th. Southern Pacific's new "Sunset Route" proved instantly popular, both with passengers and freight and Morgan pioneering of an intregated rail-sea freight and passenger network found its ultimate realization.

|

| One of the first of the new generation of Morgan liners, El Sol, depicted in a company poster. Credit: Mariners' Museum. |

The resources of Southern Pacific and the expanded business that its incorporation into its new transcontinental network transformed the Morgan Line and a new generation of ships assumed their own distinct character and qualities, making them both instantly recognizable and ranking them as among the most graceful of American merchantmen of their era.

In 1884, the Eureka, El Dorado and El Paso were built; in 1886, the El Monte, and in 1889 the El Mar. These were 14 knot ships of thirty-five hundred (3500) tons. They were followed in 1890 by the El Sol of forty-five hundred (4500) tons, with speed of 15 knots. At this time contracts for three more ships of the El Sol class were let, the El Norte, El Sud and El Rio. These ships were built and placed in commission as rapidly as possible. The last four ships were taken by the Government during the Spanish-American War and converted into cruisers. They proved so adaptable for the service that when the war was over the Government would not release them. This, of course, crippled the line and more vessels had to be built to replace them. In the meantime, the steamships New Orleans, Knickerbocker and Hudson were operated under charter. In 1899 and 1901 contracts were let and the El Norte, El Sud, El Cid and El Rio were built as rapidly as possible, followed right along by the El Valle, El Dia, El Siglo and El Alba all of the same design.

Southern Pacific Bulletin, February 1922.

|

| Showing the long and graceful lines that characterised Morgan boats, El Valle at her builders in Newport News. Credit: Mariners' Museum. |

In common with the other coastal lines, it developed, early in its career, a distinctive type of vessel, peculiarly fitted to its requirements the older Morgan liners at present in service can be recognized as far as they can be seen-but aside from their particularly distinctive appearance, the Morgan ships are deservedly known as vessels of particularly high class, both as regards hull and machinery design and construction, and the thorough and efficient manner in which they have been maintained in service.

Of these older type vessels-there are several of them still in operation-the first were built at Cramp's in the 80's. With the opening of the Newport News yard, about 1890, by the same financial interests which were back of the Southern Pacific Company, the building of Morgan ships was taken up by that company and, until quite recently, all of these vessels were built at the Virginia yard. The oldest which are still in active service are the El Sud and El Norte, built at Newport News in 1899.

|

| Builders model of El Sud. Credit: Mariners' Museum. |

Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, February 1925.

|

| Excelsior on her maiden voyage as a passenger liner, January 1901. Credit: eBay auction photo. |

The early 20th century saw considerable expansion of Southern Pacific's Atlantic Coast steamship operations. In 1900, amid the enormous increase in American commercial interest and travel to Cuba following the Spanish-American War, a new high quality passenger service was begun between New Orleans and Havana employing the former freighters Chalmette (1879) and Excelsior (1882) which were extensively rebuilt to carry 100 passengers each. The now 3,205-grt Chalmette made her maiden voyage to Havana on 18 December 1900 followed by the 3,542-grt Excelsior on 4 January 1901.

|

| The former Cromwell Line s.s. Proteus in Morgan Line colors, by Antonio Jacobsen. Credit: invaluable.com |

With the acquisition of the Cromwell line by the Southern Pacific interests, the carrying of passengers as well as freight was undertaken by the Morgan line. Of the Cromwell ships, the Comus and Proteus were, so far as their hulls and machinery were concerned, duplicates of the Morgan freighters. The other combined passenger and cargo ships, the Momus and Creole, are larger and of greater power and speed.

Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, February 1925.

In August 1902, a direct New York to Galveston cargo service was begun, complimenting that to New Orleans, and using three ships. Southern Pacific also bought out the Cromwell Line, dating from 1880, and long Morgan's chief rival on the New York-New Orleans route. This added the famous Louisiana (1880/2,849 grt) which held the speed record on the route for many years and a pair of fine liners, all Newport News-built: Comus (1900/4,428 grt) and Proteus (1900/4,836 grt). The addition of these ships enabled Louisiana to be redeployed on the New Orleans-Havana run. Finally, in 1903, the line's New Orleans terminus was shifted across the Mississippi River from Algiers to New Orleans.

Indicative of good business, Southern Pacific made its greatest investment in Morgan Line with the construction of a remarkable trio of new vessels, far and away the largest and finest yet built for American coastal service: Momus (1906) and Antilles (1907), both 6,878 grt, 440 ft. x 53 ft.) and built by Wm. Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia, with accommodation for 152 First, 58 Second and 250 steerage and powered by single-screw triple-expansion steam engines giving 16 knots) and Creole (1907/6,754 grt, 440 ft. x 54 ft.), built by Fore River Shipbuilding, with berths for 190 First and 500 steerage. Creole broke new ground being the first twin-screw turbine-powered American liner, but her Curtiss turbines were never satisfactory and replaced by triple-expansion machinery by Cramps in 1909. This splendid trio will be afforded their own monograph on this site in due course.

|

| Advertisement, 1907 mentioning the "100 Golden Hours at Sea" booklet which established the phrase describing the New York-New Orleans run. Credit: Periodpaper.com |

First appearing in the San Francisco Examiner on 13 October 1907 and used as the title of a new promotional booklet by the same time, "100 Golden Hours at Sea" was originally coined by a passenger writing an appreciative letter to management of his voyage. It summed up what, too, was a Golden Era for the Morgan Line New York-New Orleans, a veritable Belle Epoque which thrived up to the American entry in the First World War in April 1917 and reflected not only in thriving passenger trade but the wonderfully illustrated material to spur it.

|

| El Mundo, one of a quartet of fast, high capacity freighters built in 1910, as painted by Antonio Jacobsen. |

Freight carryings went from strength to strength and in 1909, the first modern, high deadweight capacity fast cargo steamers, capable of 15.5 knots and with a 6,400-dwt capacity were ordered and delivered the following year: El Sol, El Mundo, El Oriente and El Occidente.

In 1912, El Sud, El Mundo, El Valle, El Sol, El Alba, El Orient, El Norte and El Occidente were converted to oil fuel. The following year, a new oil tanker, Topila, was built to carry oil from the Mexican fields to tanks at Galveston and New Orleans (Algiers) for the ships and locomotives. Two slow freighters, El Almirante and El Capitan, each with a 6,500-ton capacity, entered service in 1916.

|

| Antilles as an Army transport during the First World War. Credit: Wikipedia Commons. |

Essential services continued following the United States entry into the First World War in April 1917. Antilles, however, was taken up as an Army transport in May and torpedoed and sunk on 17 October, three days into a eastbound voyage from St. Nazaire. Sinking in just four and half minutes, 67 were killed and 118 saved, the worst loss of American lives in the war to date. On 14 August 1918, Proteus was sunk after colliding with the steamer Cushing off Diamond Shoals, N.C.

After the war, no immediate attempt was made to replace the lost Antilles or Proteus owing to overtonnaging, low freight rates and tremendous inflation in shipbuilding prices. Still, three modern cargo ships, each with 4,000-ton capacity-- El Estero, El Isleo and El Largo, were ordered in December 1919 and entered service in 1920-21.

With the addition of these ships, Morgan Line reached its apex with a fleet totalling 28 steamers of which five carried passengers. There was, however, the first retrenchment as early as 1923 when the New Orleans to Havana route together with the now superannuated Excelsior and Chalmette were sold to Munson Line.

|

| Momus departs New York on her first voyage as an oil burner, 1921. Credit: Southern Pacific Bulletin, January 1922. |

The reconditioned Momus (converted to burn oil in 1921) and Creole maintained a weekly service between New York and New Orleans, and with a completely renewed Sunset Limited, the combined sea-rail combination proved as popular as ever. Now as Roaring Twenties came into full swing, it was time for new flagship to usher in a final era for "100 Golden Hours at Sea."

|

| Credit: Traffic World and Traffic Bulletin |

The Bienville was designed by Amos S. Hebble, marine architect and superintending engineer of the Southern Pacific, and was built in the Todd shipyards at Tacoma. After she was launched last July she was taken from the Pacific coast to New York for fitting of cabin interiors and cabinet work. The new queen ship is the last word in marine construction it being said that the steerage accommodations were more pleasant and comfortable than first-class passage in boats of a few decades ago.

The new vessel represents an investment of $2,000,000 and accommodates 237 first-class passengers and 100 third-class. In effect she will replace the late flagship Antilles of the Morgan fleet which was torpedoed at sea during the World war. Officials of the company said that her construction leaves nothing to be desired in the way of modern and commodious arrangement.

Birmingham Post-Herald, 14 January 1925.

There would have been no Dixie, a ship that came to be famous for defying fate and establishing her own measure of fortune under the most exacting conditions a craft can face, without another vessel, no less fine, that proved, within a career measured in but a few months, to be the exact opposite in terms of fate and fortune. Her name was Bienville, a ship that anticipated most of Dixie's fine physical qualities and marked a considerable advance over not only previous Morgan Line steamers, but all other American Atlantic coastal liners. The reader will indulge a telling of her story in some detail, one that forms its own chapter in the history of her eventual replacement.

|

| Credit: New Orleans States, 29 April 1923. |

The New Orleans States of 29 April 1923 first reported speculation that Southern Pacific was considering building "of a least a brace of fine combination passenger vessels of the latest design." It was stated that SP "have appropriated a fund of $7,500,000 for "the construction of the quartet of new bottoms." Of the possible pair of new passenger ships, "both of which will be the latest word in ship construction," and one assigned to the New York-New Orleans run in conjunction with Momus and Creole.

Instead, Southern Pacific sold the rights to the New Orleans-Havana run and the two oldest steamers in its fleet engaged upon it to Munson Line at the end of 1923, but proceeded with finally building a replacement for the wartime casualties Antilles and Proteus on the New York-New Orleans run.

Southern Pacific announced on 27 September 1923 that it would open bids on or about the 30th for the construction of a passenger-cargo vessel of 445 ft. length (overall), 427 ft. (b.p.) with a 57 ft. beam and a 7,000-ton deadweight capacity. Powered by a single-screw double-reduction drive geared turbine developing 6,000 hp and with a speed of 15.5 knots, steam would be generated by six oil-burning watertube boilers with superheaters. "No efforts will be spared in making the new ship one of the most luxurious in the coastwise service." In reporting the announcement, the Times-Picayune added: "This vessel will probably be followed by a second one, plans for which are now being considered by the company. As soon as the new vessel comes out, it is said one of the large vessels now in the New York-New Orleans service will be placed in the Cuban trade to facilitate the handling of the rapidly increasing freight and passenger traffic between New Orleans and Havana."

The construction of the Bienville has been watched with more than ordinary interest by Todd officials in the East, as well as competing shipyards on the Atlantic Coast, for the record time made in its construction, it is believed, will lead to other contracts coming to the coast and the recognition that the Pacific Coast steel shipyard are as capable of building fine passenger vessels as are those on the Atlantic side of the country.

Pacific Marine Review, August 1924.

It was with some surprise that it was announced on 24 October 1923, that Southern Pacific had awarded the contract to Todd Drydock and Construction Co. of Tacoma, Washington, "the award was made on competitive bids on which the Tacoma firm bid against several Atlantic coast firms." (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 25 October 1923. It was very unusual for Pacific Coast yards to win such contracts and indeed Bienville would be the largest passenger vessel built on the coast since the war. It was announced construction would begin in 30 days. The actual contract was inked on 7 November and the delivery date was set for 7 December 1924, an astonishingly short construction window.

The pride of Puget Sound, Bienville's construction was a marvel of speed and efficiency. The keel of yard no. 43 was laid on 26 February 1924 and thanks to excellent weather, only four hours total (!) was lost to poor conditions while she was on the ways.

|

| Bienville on the ways. Credit: Marvin D. Bolland Collection, Tacoma Public Library On Line Digital Collections |

|

| Bienville on the ways the day before her launching, bow first. Credit: Marvin D. Bolland Collection, Tacoma Public Library On Line Digital Collections. |

To be named Bienville, after one of the first families of Jean de Bienville, the French general who founded New Orleans when Louisiana was under French rule, "the vessel which will bear their name is regard as an aristocrat among the many vessels in service on the Atlantic coast," (Pacific Marine Review, August 1924), the new ship was sent down the ways, uniquely, bow first, at 6:00 p.m. on 16 July 1924, just four and a half months after the keel was laid during which time a total of 3,900 tons of steel held together by 802,000 rivets had been expanded in building her hull and superstructure. Literally smelling of fresh paint, her hull was given a finish coat of black and red lead the night before.

|

| Credit: Port of New York, September 1924. |

|

| Credit: Marine Review, August 1924. |

Bienville was christened by Miss Dorothy Maxson, daughter of Morgan Line Commodore Capt. Maxson who travelled to Tacoma on Southern Pacific's splendid business car Rio Grande over Southern Pacific's lines. Among those on the launching platform were J.A. Eves, President and General Manager of Todd Drydock and Construction Corp.,; D.C. Taylor general agent, Southern Pacific Lines; Edward Nugent, Secretary, Todd Drydock; A.S. Hibble, chief engineer, Southern Pacific; and H.C. Rittenson, supervising constructor, Southern Pacific Lines.

|

| Credit: The Port of New York, September 1924. |

|

| Credit: Southern Pacific Bulletin, August 1924. |

Before a cheering crowd of thousands of spectators including dozens of notables from all over the United States, the Atlantic Coastal Liner Bienville slipped into the waters of Puget Sound sharply at 6 o’clock Wednesday evening.

Pretty Dorothy Maxson daughter of the craft’s first skipper Captain C. P. Maxson, veteran- seaman and commodore of the Southern Pacific New York to New Orleans fleet, aflutter with the excitement of her first christening, sent the ship on its first voyage down the creaking ways with the crash of a bottle of champagne.

Slowly down the slippery skids the majestic liner sank and with a splash of water and crash of timbers that held her upright in the ways, she took the water as gracefully as a hydroplane landing in a sheltered bay.

A thunder of cheers went up from thousands of people lined along the docks and whistles from scores of small craft assembled for tho spectacle saluted the ocean greyhound.

From the humblest workman who took part in the assembly of the stately liner to the men whose finance and brains caused its construction all were there with their wives and families taking equal pride in seeing the ship take the water without mishap.

Tacoma Daily Ledger, 17 July 1924.

.jpg) |

| Credit: The Tacoma Daily Ledger, 20 November 1924. |

With an official party aboard including H.R. Ritterson, construction superintendent for Southern Pacific; A.S. Hebble, superintending engineer for Southern Pacific; E.J. Worrel, Chief Engineer; and Frederick Mackle, superintendent of hull construction, Todd Drydock & Construction, Bienville ran trials in Puget Sound on 17 November 1924, achieving in excess of 16 knots; "An exceptionally fine performance and a vessel acceptable to the owners in every respect." Bienville was drydocked that evening at the Todd Harbor Island plant. She then sailed on the 19th to the Port of Tacoma's Portacoma piers to load cargo for her delivery voyage to the East Coast. Among her 2,500-ton cargo was 5 million shingles (loaded at Bellingham, Washington), machinery, 2,000 tons of hay and canned goods. Thanks to the byzantine maze of anti-competitive laws governing American coastal shipping, she was not permitted to carry passengers to New York where much of her final interior outfitting would be accomplished.

|

| Credit: The Tacoma Daily Ledger, 16 November 1924. |

Bienville sailed from Bellingham on 24 November 1924 for the Panama Canal and New York and called en route at Los Angles on the 30th, sailing on 2 December. Completing her transit of the Panama Canal, Bienville arrived at Cristobal on the 10th. She made the voyage, according to a company engineer, "without a single readjustment, even to the extent of repacking a piston or valve stem, and arrived in spick and span condition." John Gardner, vice president of the Todd Drydock, made the voyage and pronounced the trip "entirely successful." He would also be aboard for her first round voyage to New Orleans. Bienville arrived at New York on the 16th.

On 30 December 1924, Bienville, at Pier 48 North River, was host to 2,000 invited guests for lunch and inspection, "the arrangement of the vessel came in for general commendation."

|

| Credit: The Brooklyn Citizen, 31 December 1924. |

Introducing a new era in American coastal shipping, Bienville sailed from New York at noon on 3 January 1925 from Pier 50 North River with 144 passengers.

Captain C.P. Maxson's principal officers and staff were Herman A. Mathis, Chief Officer; A.E. Rowe, Second Officer; J.C. Boch, Second Junior Officer; W. Blum, Third Officer; J.J. Brennan, Purser; E.J. Harrell, Chief Engineer; J.H. Landry, First Asst. Engineer; J.C. Adams, Second Asst. Engineer; R. Goodwin, Third Asst. Engineer; J. Emper, Jr. Engineer; D. Gimnie, Jr. Engineer; H. Bartholomew, Chief Steward; and L. Seibert, Second Steward.

As she entered port all other craft in the harbor signalled by means of whistles and fog horns. The water front industries also blew their whistles in its welcome. Commodore Charles Maxson, senior master of the Morgan Lines, was at the bow of the Bienville as she plied her way into the harbor amidst the din and roar of the occasion.

Formal welcome had been accorded the Bienville by the board of port commissioner who sent a delegation aboard the motor launch Alexandria to greet Commodore Maxson. Captains of other craft in the harbor went aboard the Bienville after her landing in order to inspect what some say is 'the finest vessel that ever touched New Orleans.'

New Orleans States, 9 January 1925.

Flying the Commodore's pennant at her bow, and the Morgan Line houseflag and "Bienville" pennant at the foretruck, the new flagship arrived at New Orleans on 9 January 1925, the 110th anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812. The local press dubbed her "Queen of the Coastal Fleet." Bienville tied up at 11:20 a.m., a few hours late owing to fog, but all her passengers transferring to the "Sunset Limited" for the west, departing at noon, still made their connection. Capt. Maxson told reporters "she is a bird" and said he was more than pleased with the success of the first trip and A.S. Hebble, who was along on her maiden voyage, also expressed his satisfaction.

Captain Maxson and his officers were the guests at a luncheon at noon on 10 January 1925 at the Bienville Hotel given by officials of the Southern Pacific Steamship Lines.

Tuesday, January 13, was set as the day to inspect the Bienville, on which day approximately 5000 persons, invited guests and others, visited the palatial liner, which was beautifully decorated with flowers, ferns and palms. An elaborate buffet luncheon was served to about 1600 visitors, and this, together with music and dancing, helped to make the visit enjoyable. The affair eclipsed anything of the kind ever attempted at New Orleans. The Bienville attracted a great deal of attention and admiration while in New Orleans and was thronged daily with men, women and children.

World Ports

Bienville left New Orleans on 14 January 1925 on her maiden northbound voyage and arrived at New York on the 19th. She left on her second voyage at noon on 23rd from Pier 49.

Upon arrival at New Orleans on 6 March 1925, Bienville's return sailing on the 11th was cancelled owing to trouble experienced with one of her turbine rotors. She was towed to Jahncke Dry Dock and Ship Repair Company's wharf, next to the New Orleans Navy Yard for repairs which necessitated replacing the rotor which had to be dispatched from the East and was to be installed on the 21st in time for the ship to take her next previously scheduled 1 April sailing to New York.

|

| Credit: New Orleans States, 19 March 1925. |

The fire was one of the most spectacular ever seen in New Orleans, and both sides of the Mississippi river bank were thronged with crowds that watched the vessel as it burned and the deperate efforts of fireboats and tugs to stop the ravages of the flames over the beautiful vessel.

New Orleans States, 19 March 1925.

On 19 March 1925 a fire was discovered around 10:40 a.m. in cabin no. 18 in the forward superstructure, under the officers' quarters, by First Officer Herman Mathis and Second Steward Louis Seibert. This had evidently been smouldering for some time. Capt. C.P. Maxson was immediately altered and the ship's crew attempted to tackle the blaze. Bienville's own whistles adding to the alarm, shoreside fire stations-- the Algiers Fire Dept., the Naval Station Fire Dept. and the Shipping Board Fire Dept.-- responded immediately and the Dock Board's fire boats Deluge and Samson rushed to the scene along with the tugs Sipsey, W.T. Wilmot and Adler of the Coyle Coal Co. and several Bisso Co. tugs also made for the burning vessel.

|

| Credit: New Orleans States, 20 March 1925. |

|

| The big New Orleans Dock Board's fireboat Deluge playing her hoses in a losing fight to put out the raging fire aboard Bienville. Credit: Times-Picayune, 20 March 1925. |

Then began a fight to save the big boat. From the river side water and steam were thrown upon the boat, which was pouring forth smoke from every porthole. The entire craft seemed afire. Captain Maxson kept his men on deck as long as possible but they had to retreat and several were bruised, but not painfully, in leaving the ship.

New Orleans States, 19 March 1925.

The speed and ferocity of the fire was tremendous, the ship issuing vast quantities of smoke although no fire was seen from outside. Several companies of Algiers and New Orleans firefighters attempted to fight their way from her stern forward and quantities of water played upon the superstructure. Officers and men of the Navy Yard and U.S. Marines also pitched in to fight the fire When the vessel suddenly lurched away from her pier, Fire Chief John M. Evans ordered his men to evacuate the ship. A half dozen or more stuck with the vessel and tried to get a hose into her interior.

|

| Credit: New Orleans States, 19 March 1925. |

When the listing ship appeared to be ready to pull the wharf with her seeming about to capsize on her starboardside, Capt. Maxson had his crew cut her mooring lines with axes. At 12:35 p.m. the burning Bienville swung out by half a dozen tugs and as she was facing up river, had to be turned around completely. In doing so, she was exposed to the prevailing wind which swept over her, fanning the fire and eliciting flames and "in short time the vessel was one blaze from bow to stern and presented an awe-inspiring sight as the tug swung it around on steel hawsers. The flames mounted high in the air, even going above the masts and the smokestacks of the boat. The tugs started to swing the craft around, and started downstream. The flames continued to lick greedily at the mahogany and other fancy furnishing in the boat, and as the tugs dragged the craft down-stream the boat was listed at angle of 45 degrees. This made the tugs pull slowly but the gradually worked the Bienville down the river while flames played up and around the smokestacks and masts. Every now and then there were minor explosions heard. The boat was slowly taken down stream and run into shallow water and beached, while the fire tugs continued to fight the flames." (New Orleans States, 19 March 1925.)

|

| Credit: eBay auction photo. |

Bienville was towed five miles down river, just below Chalmette and beached in shallow water around 1:30 p.m.. Surrounded by a dozen tugs pouring water on her, the fire was finally largely out by 5:00 p.m.

Captain Charles P. Maxson, commodore of the Southern Pacific fleet, worked himself into exhaustion in combating the flames and it was not until the vessel had been beached and the fire extinguished that he gave way to an unconquerable dejection.

New Orleans States, 20 March 1925.

Voicing the praise of marine and sailors together with employees of the various towboats and the crew of the Deluge and Davey, specatators paid tribute to the courage of Captain Maxson and members of his crew.

"The veteran ship master, whose designation as commodore came some time ago after he had been designated to command the Bienville, then under construction at Tacoma, Washington, wore an air of sadness that was not hidden in the fervor of his action to combat the destroying force which had robbed him of his new ship, realization of many years dreaming on the bridge. Into smoke filled companionways he went ahead of his men taking a hand at hoselines and going from one point of vantage to another. Amid the slush and through the ankle deep much that accumulated on the starboard side of the cabin deck from the charred remains of the superstructure the veteran captain braved the fire and smoke."

The Times-Picayune, 20 March 1925.

Bienville, now presenting a dismal sight and her interiors completely consumed by the fire and her upper superstructure twisted and distorted by heat, was even by the late afternoon of the blaze, considered a write-off as a passenger ship whose prospects were either complete rebuilding as such, scrapping or conversion into a cargo ship. Early on 20 March 1925, she was towed back to her original wharf where it was quickly determined her hull and machinery were all but undamaged.

Meanwhile, inspectors from the American Bureau of Shipping, the Underwriter's Bureau and Southern Pacific commenced inquiries into the cause of the fire, ascertaining the extent of the damage and feasibilty of rebuilding her for some purpose. On 23 March 1925, a conference between Southern Pacific's manager S.I. Cooper and insurance representatives was held aboard Bienville and it was agreed to conduct a formal survey of the ship as soon as practical.

Over 100 of Bienville's crew sailed in Momus on 25 March 1925 for New York, but Capt. Maxson, Chief Engineer Worrell and his assistants remained by the ship until she was ready to sail for "a North Atlantic port to be repaired. Bids have been invited from several ship building companies for the reconstruction of the vessel, but it will be some little time before the contract is awarded." (Times-Picayune, 26 March 1925).

Construction of a new passenger steamer to replace the Bienville in this branch of service will be given early consideration, according to official announcements by Lewis J. Spence, executive officer of the Southern Pacific Steamship Lines. This statement was made simultaneously with the award of the contract for converting the Bienville to a freighter.

Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, May 1925.

Dixie's origins were literally Phoenix-like and the decision to build her was made simultaneously with the rebuilding of Bienville into a cargo vessel. Bids to convert Bienville were opened 9 April 1925 and on 7 May, Robins Dry Dock & Repair Co., New York, won the contract worth $819,000 and to take 225 days.

Decision to convert to an exclusively freight vessel the new passenger and freight steamer Bienville, which, soon after her maiden voyage between New York and New Orleans, was partially destroyed by fire, has been announced by Lewis J. Spence, executive officer of Southern Pacific Steamship Lines, and the contract for conversion has been awarded to Robins Dry Dock & Repair Company, of New York. The adoption of this plan will provide a substantial addition to the cargo capacity of these lines within less than half the time that would be required to restore the vessel as a passenger steamer and the cost of conversion to a freight vessel will be substantially less.

The construction of a new passenger steamer for the New York-New Orleans service will not require very much more time than the reconstruction of the Bienville as a passenger vessel would have required, and the question of building a new passenger steamer will therefore be given early consideration.

Southern Pacific Steamship Line's press release, May 1925.

Charles S. Fay, southern freight agent of Morgan Line, announced in New Orleans on 7 May 1925 the decision to rebuild Bienville into a cargo ship and that "early consideration will be given to the question of constructing a new passenger steamer for the New Orleans-New York service. Part of the contract with Robins specified that she would sail to New York under her own steam. To accomplish this, repairs were effected to windows and ports, a new steering control installed and pilot and chart house installed. With Capt. Maxson on a makeshift bridge, Bienville departed the morning of the 13th for New York.

The Todd Shipyards Corporation was the successful bidder for this work. Temporary repairs were made to the vessel's hull and to such of the machinery affected by the fire, new steering control system and communicating system between bridge and the engine room installed, and the vessel was moved to the Robins plant at Brooklyn.

Her lower-most passenger deck was removed and completely rebuilt, both smoke stacks, fiddley, engine and boiler casings were entirely removed and rebuilt. The mainmast was also removed and rebuilt, as the heat had buckled it considerably. The steerage and crew's quarters below weather deck were completely removed, together with the steel bulkheads which enclosed them. New cargo ports were fitted and some of the existing ones were relocated to suit new conditions.

The forward end of the bridge deck enclosure was fitted up to carry cargo. In the after end of this space the engineers, firemen, oilers, water tenders, and cook's quarters were constructed, as well as a mess room for the captain, officers, and firemen. The galley and ship's provision chambers adjoin these quarters, the entire layout affording spacious and convenient quarters. The captain's and officers' quarters, pilot house, chart room, navigating bridge, hospital, and radio room are constructed above the bridge deck space.

Pacific Marine Review, October 1925.

|

| The Bienville as rebuilt into the cargo ship El Coston. Credit: Mariner's Museum |

The reconditioning and conversion to a freight vessel of the steamship El Coston owned by the Southern Pacific Company, New York, has recently been completed by the plant at the Robins Dry Dock & Repair Company, Brooklyn, N. Y., in the record time of 105 days which was 20 days ahead of the time specified in the contract. This vessel, which is 445 feet overall by 57 feet beam and 37 feet 6 inches depth, was formerly the steamship Bienville and was built at the Todd Dry Docks & Construction Corporation's plant, Tacoma, Wash., last year.

Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, October 1925.

El Coston (Capt. W. Patten) sailed from New York at the end of August 1925 and made her first arrival at Galveston on 2 September. With a cargo capacity of 7,500 tons, she remained on the New York-Galveston run and with her advent, Morgan Line maintain a tri-weekly frequency on the route.

Even if denuded of its shortlived flagship, Morgan Line's 50th anniversary in 1926 was suitably celebrated by the contracting of her replacement. The $2.4 mn. order for a "coastwise passenger and freight oil-burning steamer with a displacement of 12,000 tons and a speed of 16 knots an hour" was reported placed with Federal Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co. on 19 April 1926. All the new ship's specifications were released at the same time, calling for a vessel of 445 ft. with a beam of 60 ft, and powered by single-screw steam turbine. Accommodation would be for 279 First and 100 Third Class. It was anticipated the new vessel would be "completed during the summer of 1927."

Contrasted with the small steamers of the original fleet is the 12,000-ton oil-burning passenger and freight steamship, not yet named, to be used in whatever service the company may find it most advantageous and profitable to have it engage, that is being built for the Morgan Line by the Federal Shipbuiding and Dry Dock Company at Kearny, New Jersey, at a cost of over $2,400,000, to signalize the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of this service. When this steamer, which will embody the latest developments in marine architecture for comfort and luxury, economy and efficiency and for the prevention and control of fire, goes into service, the steamships of the Morgan Line will have 139,754 gross tons register.

New Orleans States, 5 September 1926.

|

| Credit: Pacific Marine Review, July 1927. |

Few ships were as neatly accomplished in such short order as Dixie was by Federal Shipbuilding. Her keel was laid on 31 January 1927 (yard no. 89), she was launched on 29 July, made her trials on 10 December and was off on her maiden voyage on 28 January 1928, all just shy of a year. So quick and efficiently was Dixie built that there were no even the customary "progress reports" accompanying her building nor the usual tweaks in her design or appearance. So in less than seven months, she was not only ready for launching but her superstructure erected and masts fitted.

The Southern Pacific Company's new coastwise passenger steam-ship Dixie was launched July 29th at the Kearny yard of the Federal Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company. Mrs. Lewis J. Spence, wife of the Executive Officer of the Southern Pacific Company, acted as sponsor before a large gathering of officials and friends.

Nautical Gazette.

Sent down the ways around noon on 29 July 1927 by Mrs. Lewis J. Spence, wife of Southern Pacific Executive Office, the new ship was christened Dixie, the name having, it seems, not being preannounced, and ideally suited for what would be Morgan Line's final passenger steamer. Present at the launching ceremony were Capt. C.A. McAllister, President of the American Bureau of Shipping; S.I. Cooper, William Simmons and Lewis J. Spence of Southern Pacific; and S.H. Korndorff, vice president of the Federal Shipping & Dry Dock Co. "Nearly a thousand persons witness the launching ceremony yesterday and about a third of theses as guests of the building company were served luncheon in the offices of the company." (The Jersey Journal, 30 July 1927).

|

| Credit: The Nautical Gazette. |

Mr. Lewis J.M. Spence, executive officer of the Southern Pacific Steamship Lines, when interviewed by the Nautical Gazette was justly proud of the new turbine steamship Dixie just built for his company by the Federal Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company at Kearny, N. J.. The Dixie was officially launched at the yards on Friday, July 30, and as Mr. Spence says, 'it was a beautiful launching.' Mrs. Lewis J. Spence was sponsor and broke the bottle of champagne exactly over the figure '13' on the draft markings, thus efficiently dispelling any hoodoo that might otherwise rest on the ship. After the christening ceremony the party was entertained to a recherché lunch and thus another good ship was well and truly launched with time-honored observances.

Nautical Gazette, 6 August 1927.

|

| Credit: Southern Pacific Bulletin, September 1927. |

Mrs. Lewis J. Spence sponsor For New Steamship Dixie. Mrs. Lewis J. Spence, wife of the executive officer of the Southern Pacific Company, of Argyle Rd., Flatbush, and Brightwaters, L.I., was sponsor for the Southern Pacific Steamship Line's new 12,000-ton passenger and freight steamship Dixie, which was launched last Friday at the yards of the Federal Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, Kearney, N. J. In addition to L. H. Korndorff, vice president of the shipbuilding company, and Mrs. Korndorff, Mr. and Mrs. Spence and their son, Lewis A., and daughter, Cecil A. Spence, there were present from Brooklyn Harris M. Crist, Mr.and Mrs. George W. Spence, George L. Spence, Dr. and Mrs. George H. Iler, Prof. William Cadman Hardy, Mr. and Mrs William Bishop, Miss Madeline Bishop, Miss Elberta Baldwin, Mr. and Mrs.J. Franklin Tausch, Miss Doris Tausch, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas F. Diack and Mrs.Dolly King.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 2 August 1927.

Last Saturday the Southern Pacific S.S. Company launched the 12,000-ton passenger steamer Dixie from a New Jersey shipyard to join the Creole and Momus in the New York-New Orleans service demands upon which have been such that reservations must be made weeks ahead. The new steamer is 445 feet long, 60 abeam and 37 feet deep. Among the modern features will be hot and cold fresh and salt water baths and a swimming pool. She will run 16 knots and carry 379 passengers and freight. It may have been appropriate to break a bottle of champagne over the bow of the Dixie in the state of Senator Edwards, but what about drenching with an unlawful beverage the dry name of Dixie, where we naught to drink but artesian gun and salt-water vermifuge. It leaves us in doubt.

We are thankful duly that this handsome boat, which will connect the greatest port of East with the greatest and fastest-growing of the South, is to be named Dixie, which all of us love. Now, if the Morgan Line will run run from the Mississippi port, named The Gulfport, or The Biloxi, our cup will be full, and not a tear in it.

Sun Herald (Biloxi), 5 August 1927

At the time of Dixie's launching, her commander, Charles P. Maxson, (1862-1941) formerly captain of Momus and Bienville was appointed and "was in charge on the bridge when the ship slipped down the ways and glided into the water." (New Orleans Item, 29 July 1927). Capt. Maxson was one of the most legendary of American sea captains, who on his retirement in 1930, chalked up 46 years at sea and was the last to have sailed under the legendary Charles Morgan. The soon to be skipper of Dixie was a died in the wool Yankee, a descendent of Richard E. Maxson, first white child born in Rhode island and his father built the first Union ironclads, Galena and Vicksburg, in the Civil War. Maxson often said, "In the cities you may sometimes lose sight of God, but I always find him the minute I get out of sight of land."

On 14 October 1927 the New Orleans States reported that upon Momus' arrival at the port that her Chief Steward H. Bartholemew and Purser John J. Brennan would be joining Capt. C.P. Maxson aboard the new Dixie.

Accomplished in complete press disinterest, Dixie successfully ran her trials on 10 December 1927 and there seems no record of her performance or maximum speed. Evidently successful enough, it was announced six days later that she would sail from New York on 28 January 1928, arriving at New Orleans on 3 February with her first northbound voyage beginning on the 8th and returning to New York on the 13th.

|

| Credit: Nautical Gazette, 31 December 1927. |

|

| Dixie (artist: Meredith A. Scott) in a stormy setting, possibly inspired by her remarkable experience in the great 1935 hurricane. Credit: eBay auction photo. |

In construction and equipment, a standard well above the average of operating efficiency and economy has been achieved. The safeguards of passengers and crew, such as wireless, life-boats, prevention, detection and control of fire by steel decks, steel fire screen bulkheads, and steel doors in passageways, fire-proof partitions, ceilings and panelings, automatic fire detector system, Lux fire extinguishing system and manual alarm system, are unsurpassed.

World Ports, June 1928.

'Better than ever,' was Captain Sundstrom's verdict. 'But she was mighty good ship before. With all the pounding she took on that reef there was never a hole driven through her-- only dents and stove-in plates.'

New Orleans States, 17 December 1935.

Earning the sobriquet of "The Staunchest Ship," Dixie's remarkable survival, together with everyone aboard, during what remains the worst hurricane to hit the U.S. Eastern Seaboard, the infamous 1935 Labor Day Hurricane, was as much testiment to her officers, crew and passengers as her stout qualities as a ship. But coming on the heels of the unfortunate Bienville, her qualities were even more admired and she remains an exemplar of naval architecture, construction and, at the time, was a true pioneer in the American merchant marine, being the first ship fitted with high pressure boilers.

If the 1920s witnessed a significant revival of the American Passenger Liner in number, quality, design and innovation, it also saw a final contribution to one of its most characteristic and unique type: the ocean coastwise vessel. With many of its largest cities, both in population and industrial and commercial capacity, also being major ports and with distances between them greater than most other countries, made sea travel between them attractive for American coastal passengers and renumerative for cargo, especially package freight, household effects and upon their introduction and astonishing expansion after the First World War, automobiles. Yet, by the end of the war, many of the leading coastal operators were cautious in renewing their fleet amid high construction costs, faster and more efficient railroad links and even the first domestic air services.

Mallory Line, long the great rival of Morgan Line, had pretty much given up on their traditional New York-Texas passenger service by the mid 1920s and had not commissioned a new vessel since Henry R. Mallory in 1916. In 1928, it merged with Clyde Line to form Clyde-Mallory Lines. And it was Clyde Line, operating mainly from New York to Florida, that had been the most ambitious in its inter-war newbuilding program with its "Chiefs Class"-- Cherokee (1925), Seminole (1925), Mohawk (1926) and Algonquin (1926)-- capable if conventional "shelter deckers" of 5,896-grt, 387 ft. x 55 ft., single-screw and turbine-powered that were omnipresent on the many routes operated by the company especially after it became part of the sprawling AGWI combine in 1928 when Mallory was absorbed into it as well. It was Clyde-Mallory/AGWI that produced the impressive 6,209-grt, 395 ft. x 62 ft. twin-screw and twin-funnelled Iroquois and Shawnee of 1927 for the New York-East Coast of Canada route.

Yet, none of these, nor Eastern Steamship's 6,182-grt, 387 ft. x 51 ft. Saint John and Acadia of 1932 (which were the last of their kind to be built), held a candle to Morgan Line's recent fleet in size or capabilities as true trans-ocean steamers. With Momus at 6,878 grt, and Bienville at 7,916 grt, these scales of comparison were further tipped by the new flagship which, while not the last American Atlantic coastal liner to enter service, was, by a considerable margin, the largest at 8,188 grt and 426 ft. x 60 ft. In reality, Dixie was actually only nominally larger than Bienville and same in overall length but three feet greater in beam which accounts for her greater tonnage.

|

| Bienville's distinctive profile. Credit: Mariners' Museum. |

The latest Morgan ship, the Bienville, has but just entered service. While, in some minor respects, a certain similarity to the older vessels may be traced in the new ship, she is essentially a complete departure from anything that has gone before and in every respect embodies the latest developments in hull construction, machinery and passenger accommodation.

Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, February 1925.

|

| Bienville profile. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

|

| The impressive but star-crossed Bienville in Puget Sound following her trials. Credit: Steamship Historical Society of America. |

In every respect, the progenitor of Dixie in design, build and décor, and her fated fortunes occasioning her construction in the first place, Southern Pacific's ill-fated Bienville is deserving of more than passing mention in anticipation of her replacement.

|

| A.S. Hebble, Superintending Engineer, Southern Pacific Steamship Lines. Credit: Pacific Marine Review, March 1925. |

Designed by Southern Pacific's A.S. Hebble under the direction of C.W. Jungen, manager of Southern Pacific's Atlantic Steamship Lines, Bienville was built on the Isherwood system of longitudinal framing with three complete steel decks and seven watertight compartments. She had a cargo capacity of 405,000 cu. ft. and 1,200 tons of fuel. She was, compared to the Momus-trio, more of a conventional coastal liner with her hurricane type arrangement and low superstructure extending to the stern and had larger First Class capacity.

The Bienville is a single screw ship of the hurricane deck type, having 4 complete steel decks and an orlop deck in the forward hold. A bridge superstructure, of steel, about 160 feet in length, is erected on the hurricane deck with a steel house at its after end. Above these is the promenade deck, extending from the forward end of the bridge to the stern and on this deck is a long house, also of steel. Above the promenade deck, and of equal length, is the boat deck upon which are detached steel houses for the officers' quarters, navigating spaces, smoking room and lounge.

The hull is framed on the Isherwood system and has a complete double bottom and 7 transverse water- or oil-tight bulkheads. Fuel oil is carried in 2 deep tanks, one forward and one aft of the boiler room, both divided into 3 separate compartments by longitudinal bulkheads. Twenty hinged side ports are fitted for handling cargo.

There are 2 masts, the forward one equipped with 4 and the after with 2 cargo booms, and 2 funnels. Cargo from No. 2 and No. 4 holds is handled by "blind" hatches under the quarters and in way of the side ports.

237 First Class and 111 Third Class. 24 in deck dept and 66 in steward dept.

The passenger accommodations are unusually commodious, the provision of ample space and "elbow room" is in evidence throughout the passenger quarters and the public rooms.

The first class passengers are berthed in the bridge and deck house on the hurricane deck and on the promenade deck. Each stateroom is paneled in white and is fitted with an extra wide bed and mahogany Pullman berth over, both with coiled bed springs. A pull-out spring upholstered davenport, which can be converted into a full width berth is also provided. All staterooms are supplied with running water. In addition to the ordinary rooms, 6 suites with connecting bath are fitted up in the promenade deck house.

The third class passengers are berthed in rooms on the main deck forward, and the deck crew in the winch house on the hurricane deck.

The dining saloon is located in the forward end of the bridge house and has a seating capacity of 200 at small tables, accommodating 4, 6, or 8 persons each. The finish is of colonial design with mahogany wainscoting and white panel above and between the beams overhead. Steward air ports, 20 inches in diameter, are fitted across the forward bulkhead and at the sides. The pantry is abaft the dining saloon and extends the full width of the ship. The galley and ship's refrigerating rooms are on the main deck, forward of the boiler casing.

Special attention was paid to the passenger foyers, passageways and stairways which were finished in white enamel with mahogany wainscoting, ceiling beams capped and with sunken panels between them and decks of marbled rubber tile with an abundance of small tables, tapestry upholstered armchairs and davenports in the foyers and social halls off the cabins.

Cabins were finished in white enamel and each had an extra wide metal lower lower berth, folding mahogany upper berth and a pull-out spring tapestry upholstered davenport which would be converted to another bed. Each had a large mahogany wardrobe, dressing table, washbasin with hot and cold running water, thermos bottle and ample coat hooks. The portholes had tapestry curtains and the deck laid in rubber tile with Lowell-Wilton carpet. Each berth had a 25-watt reading lamp and there was an electric fan and electric-vapor radiator.

The music room is in the forward end of the promenade deck house, paneled in white, in colonial design and fitted with mahogany furniture. The passage ways, social halls and lobbies are finished with mahogany wainscoting and white panel work.

The smoking room and lounge are in a separate house on the boat deck, the former finished in quartered oak and the latter in white and mahogany. Three large French doors are fitted at the after end of the lounge, opening on deck.

Throughout the joiner work, plywood has been extensively used and the ceiling and passageway panels are of agasote. The flooring is of rubber fiber tile. The showers, baths and toilets are fitted up in the most modern manner and have tiled floors.

The deck equipment and outfit are most complete, in every respect. Twelve lifeboats are carried, under Welin mechanical davits.

The propelling machinery consists of De Laval turbines driving the single screw shaft through double reduction gears.

Seventy-one hundred shaft horsepower is developed with the propeller making 85 revolutions per minute, giving the ship a sustained sea speed of 16 knots.

Steam is supplied by 6 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, burning oil and having a total heating surface of 21,576 square feet. The boilers are fitted with superheaters having a surface of 3,668 square feet. The working pressure is 250 pounds per square inch and superheat 100 degrees. The Babcock and Wilcox system of fuel burners is installed.

Special attention has been given to the lighting of the quarters throughout the ship and in the various public rooms and spaces, fittings of special design and finish, to harmonize with the surrounding decorations, are installed. The electric generating plant consists of two 50-kilowatt and one 25kilowatt engine-driven sets of Sturtevant make.

The following features were among those sought when preparing the design and specifications were in course of preparation. A visit to the vessel demonstrates how very successfully the intentions of the designer have been materialized:

- All furniture is of special design and made to resemble hotel, club or home furniture, being heavily upholstered and comfortable.

- High ceilings throughout the passenger spaces give air and comfort.

- A light mahogany finish throughout brightens up the inside, inasmuch as the light inside the compartments of a ship is always more or less subdued.

- Long narrow panels give height to the joiner work. The joiner work is all plain and rich without carving or trimmings.

- The floor covering is of special color and all laid plain. with broken grain.

- The observation lounge is specially arranged with high windows to give maximum light and air. A large dance floor, 20 by 26 feet, is equipped with an electrically operated phonograph.Tables in the smoking room and lounge are covered with marbleized rubber.Art glass domes of special design give warmth of coloring and light.

- All berths are 34 inches wide, which is unusual on shipboard.

- The promenade space on the promenade deck is 700 feet long. There is also a large amount of deck space on boat deck and hurricane deck aft.

- The forward end of the promenade deck is enclosed with portable glass windows to add comfort in cold or rainy weather.

- Hinged decks in way of the after hatches facilitate working out the after end of the ship, and give an unobstructed promenade when the hinged portion of the deck is in place.

- A large number of skylights are provided throughout for ventilation.

- All outside staterooms are fitted with large sliding windows operated from the inside. Thermos bottles and running water are available in all staterooms.

- The ship is well protected against fire. Every room is fitted with an electric thermostat. The holds and cargo spaces throughout are fitted with the Rich fire detecting system. The ship has 34 hose outlets and 1,600 feet of fire hose; also there is a large Firefoam installation in the boiler room for handling oil fires.

- No passengers are carried below the hurricane deck; the entire vessel below this deck is devoted to cargo space. The machinery equipment is undoubtedly one of the most economical steam propelling units ever placed on shipboard. The auxiliaries and condensing plant are of large proportions and designed especially for tropical waters.

Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, February 1925.

|

| Credit: Southern Pacific Bulletin |

|

| Dixie departs Kearny, New Jersey, on her trials. Credit: U.S. National Archives. |

For Dixie, A.S. Hebble revised and improved upon Bienville in certain essential aspects, including her dimensions (three-feet greater beam to give better stability) and a more modern steam plant which would, in fact, be pioneering for American merchantmen. She would also present a more modern appearance with one funnel rather than two slender "pipes" of her elder near sister. There were also significant changes in her interior joinery and fittings, using the new Vehisote lightweight fireproof sheeting which reduced her topside weight.

Dixie was designed under the direction of Lewis J. Spence, executive officer of Southern Pacific who "with the advice of a distinguised naval architect and a professional interior decorator personally supervised the arrangement, decoration and furnishing of the vessel."

The Dixie was designed by A. S. Hebble, Superintending Engineer of the Southern Pacific Steamship Lines, who had immediate charge of construction under the direction of Executive Officer Lewis J. Spence, who personally supervised the arrangement, decoration and furnishing of the vessel. So much thought and personal attention did Mr. Spence devote to the details of the Dixie, from the laying of the keel until the completion of its initial voyage, that it is regarded by the staff as 'Spence's ship.'

World Ports, June 1928.

|

| Credit: Marine Review, October 1926. |

Amos Sherman Hebble for many years has been recognized as one of the outstanding figures in the field of marine engineering and ship design. As superintending engineer of the Southern Pacific Steamships Line, he is responsible for the design, construction and physical condition of the entire fleet. Inasmuch as this fleet comprises 25 ships and some 75 harbor craft, it at once becomes apparent that this is no ordinary task. naval architect he has won renown for his fearlessness in making departures from standard practice. His latest exploit is the design of a Southern Pacific express liner, now under construction by the Federal Shipbuilding Co. at Kearny, N. J. This ship will have a steam boiler pressure of 350 pounds per square inch and 200 degrees of superheat, which is 100 pounds in excess of any pressure previously employed in marine power plants.

From Mr. Hebble's start in life it would never have been suspected that he would develop into one of the country's foremost marine engineers. He was born in Gloucester county, Virginia. His father was a native of Lancaster, Pa., who had moved to Virginia, married there and set up a 2,700-acre stock farm. While Amos was still an infant, his folks moved to Lancaster. When he was seven, the family moved back to Virginia. It was at that time that the boy first developed an interest in steam engines. Among his father's interests was a saw-mill and young Amos used to like to watch the machinery at work. The power unit was a 10 x 12-inch, horizontal, center-crank engine, mounted directly on the boiler, the whole unit placed on wheels so as to be portable. Under the tutelage of his father, who was a man of considerable mechanical ability, the boy was able to get pretty well grounded in the workings of this engine.

The family moved to Baltimore when Amos was 12, and it was in that city that he received his schooling. After finishing his education, he went to work in a machine shop in Baltimore. But he felt the lure of the sea and at the age of 20 went with the Baltimore & Washington Steamboat Co. which operated the Norfolk and the Washington, since rechristened the Lexington and the Concord. The following year he went with the Bay Line, plying between Norfolk and Baltimore. With this preliminary experience he was ambitious to move up a peg. At the age of 22, he came to New York and shipped as an oiler on the steamer El Paso of the Southern Pacific Co.-Atlantic Steamship lines, now known as the Southern Pacific Steamship lines. Mr. Hebble served as an oiler for only a few months. He served in various capacities as assistant engineer and then was made a chief engineer and served in that capacity on several Southern Pacific ships. In 1905 he was appointed assistant superintending engineer, with headquarters in New York. In 1907 he was appointed superintending engineer, the post which he continues to occupy. In July, 1926, therefore, Mr. Hebble rounded out his thirty-first year in the marine business, a continuous service of 29 years with the Southern Pacific, and his nineteenth year as superintending engineer.

Mr. Hebble has designed and superintended the construction of the following boats for the Southern Pacific Steamship lines: El Sol, El Mundo, El Orientete, El Occidente, Topila, Torres, El Capitan, El Almirante, El Isleo, El Lago, El Eestero and the Tamiahua, El Coston, El Oceano, as well as the new vessel now under construction at Kearny.

E.C. Kreutzberg, Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, October 1926,

|

| From astern, Dixie had a classic American coast liner appearance. Credit: Mariner's Museum. |

Measuring 445 ft. (overall), 426 ft. 6 inches (b.p.) and with a beam of 60 ft. 2 inches, the 8,188-ton (gross), 6,900-ton (deadweight) and 12,160-ton (displacement) Dixie drew 25 ft. 6 inches and was in all respects a substantial and very strongly constructed vessel both in her specifications, scantlings and style and rather more impressive in these qualities than the traditional American "shelter deckers." Her staunch qualities would earn her a legendary reputation during her ultimate test in mid career.

Dixie was, in fact, the largest vessel ever commissioned specially for the U.S. Atlantic coast service and exceeded in size only by the bi-coastal trans-Panama Canal liners California, Virginia and Pennsylvania for domestic U.S. routes and, on the Pacific Coast, by H.F. Alexander (ex-Great Northern) (8,255 grt, 509 ft. x 63 ft.). Dixie was indeed larger than some Atlantic liners, compared, for example, to Furness' Nova Scotia and Newfoundland of 1925 at 6,791 grt, 406 ft. x 55.4 ft. and faster, too: 15.75 vs. 15 knots and approximated the initial pre-war "M" class ships of British India Line (Malda, etc. of 7,884 grt, 450 ft. x 58 ft.) dimensionally.

|

| Dixie midship section. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

The vessel is of the hurricane deck type with steel superstructure with straight stem and semi-elliptical stern. She will be rigged with two pole masts and fitted with one smoke stack. Three complete decks will extend fore and aft with an orlop deck in the forward hold to insure ample strength and stiffness. The promenade deck, approximately 8 feet wide, extends all around the superstructure. The passenger quart ers will be located on the saloon, promenade, and boat decks. The division bulkheads around these accommodations will be of steel, and the deck over and deck below of steel, making them absolutely fireproof. The deck and engine officers' quarters, together with the messroom and wireless rooms , will be located on the boat deckaround boiler casing on the forward end. The waiters and cooks will be located on the main deck aft and the firemen and oilers on the main deck amidships. The seamen are berthed in a deckhouse forward on the saloon deck.

The vessel is fitted with a double bottom throughout. Double bottom tanks under the deep fuel oil tanks are used for fuel and for fresh water, ballast, and boiler feed water. Deep fuel tanks ranged forward and alongside of the fireroom and extend from the shell to the under side of the lower deck.

Pacific Marine Review, July 1927.

Built, like Bienville, on the Isherwood system of longitudinal construction with scantlings equal to the requirements of the American Bureau of Shipping, Dixie's hull was subdivided by seven watertight bulkheads, extending as high as the saloon deck, and two oil tight bulkheads extending to the lower deck.

Dixie had two full length superstructure decks: "A" (Boat) and "B" (Promenade) and two full hull decks: "C" and "D" (tween deck cargo with Third Class right forward.

"A" Deck had the pilot house and deck officers' accommodation forward and engineers' accommodation amidships around the funnel with a block of 18 First Class cabins. These were arranged with cabins for gentlemen on the portside and for ladies on the starboard with adjoining public baths and toilets and a lobby lounge aft. A separate aft deck house had six passenger cabins, the barber shop, smoking room and observation sun parlor. Nine lifeboats and one motorboat were located on this deck as well as open promenade and sports deck space.

"B" Deck had a walkaround promenade deck which was glass-enclosed for 70 ft. of its length forward. The First Class lounge and music room was right forward with two large suites just aft and leading to the large forward lobby with its impressive curved staircase leading down to the dining room. Towards amidships athwart the funnel casing were the four remaining suites, two on each side. Amidships was the main lobby and stairway with 16 First Class cabins aft. From amidships to right aft were 20 cabins and two smaller suites in a separate deckhouse. This had, in typical American coastal liner fashion, a large inside "social hall" the outside cabins opened out onto. One distinctive southern feature was the provision of a "sewing room" on the starboardside aft.

"C" Deck, in the hull and corresponding to a Main Deck, was enclosed for two-thirds its length forward to aft of amidships. Forward with large ports on three sides was the First Class dining saloon seating 210, accessed from "B" Deck via a curved staircase and from the starboardside of "C" with large shared bath cabins on that side and the galley on the other. The main entrance lobby and staircase was amidships with purser's office. Large shared bath cabins were slightly aft and another block of cabins, with private toilet, further aft, which opened out onto a another "cabin saloon" or lounge inboard. A final bock of standard cabins was situated right aft.

"D" Deck was devoted to 'tween deck cargo with the exception of the entire Third Class accommodation block right forward, consisting of 11 cabins, four or two-berth, all outside with the two-berth ones being inboard on the Bibby system. These open onto the dining space inboard with toiled and showers forward.

|

| General arrangement plan of engine and boiler rooms of the steamship Dixie. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

|

| Credit: Pacific Marine News. |

The Dixie, which is the latest addition to the Morgan Line fleet running between New York and Gulf ports will be a fast passenger and freight steamer equipped with the most modern accommodations for passengers, while the application of high steam pressures and temperatures to her machinery are a progressive departure from the usual marine practice.

The machinery installation on this vessel sets a standard for high operating efficiency that is well above the average. Not only has a highly economical main unit been installed, but careful attention has been given to auxiliaries so that a high over-all efficiency may be obtained with a thoroughly rugged and reliable installation.

American Shipping, 1927.

Of special interest was Dixie's very-up-to-minute machinery and she was one of the very first American merchantman and passenger liner to have the newest high pressure superheated boiler installations as pioneered by Canadian Pacific Duchesses. Interestingly, this was fitted to her while her exact contemporary California for Panama Pacific Line, while pioneering turbo-electric propulsion in liners, had conventional boilers while her sisters, Virginia and Pennsylvania followed Dixie's example with high pressure boilers.