Hope have we won from out despair,

And joy out of pining.

Fast anchored, safe in waters fair we've lain at rest.

Hark! From afar on wider quest, life calls us now.

Then up anchor, spread the sails and point the prow where Hope is shining.

The New Commonwealth, Ralph Vaughan Williams, words by Harold Child

Of all Canadian Pacific's post-war passenger ships, Beaverbrae was unique. Far removed from the glamour of the "White Empresses," her more prosaic purpose being the carriage of a different generation of New Canadians, specifically the human flotsam and jetsam left in the wake of the Second World War-- the tens of thousands of Displaced Persons, refugees and war brides from Germany, Poland, Ukraine and the Baltic States-- to new lives in the Dominion. As such, she was to post-war Continental immigration to Canada what the pre-war C.P. liner Metagama was to earlier English, Scottish and Irish migration. Beaverbrae, herself German-designed and built, has been aptly described as "The Mayflower of German Immigration to Canada."

As a ship, Beaverbrae was as distinctive as her purpose, then being the only deep-sea Canadian-registered passenger ship with an all-Canadian crew, the largest Canadian merchantman, Canadian Pacific's first motorliner and their only liner serving Continental ports. No luxury liner, she carried cargoes of Canadian grain, flour and beef eastbound to help feed a war-depleted Britain and westbound, accommodated her human cargo in utilitarian dormitories, offering a safe passage but little in creature comforts. Getting there was not half the fun, yet for some 38,000 their crossing in Beaverbrae opened a new chapter in their lives and enriched the Dominion with a new generation of citizens.

Unlike today's frivolous cruise ships, the humble little Beaverbrae was a vessel of purpose that figured in the fortunes and futures of her passengers like none other. As it was, she endured for a remarkable 59 years, but here our focus is her first 15 during which she went from being a triumph of German marine engineering to war service under the swastika to go on, flying Canada's Red Ensign, to restore so many lives uprooted and degraded by the war and its aftermath.

|

| D.E.V. Beaverbrae, 1948-1954, photographed in the English Channel, 1 June 1952. Credit: Skyfotos. |

|

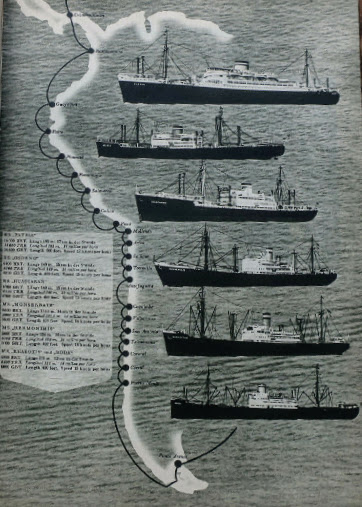

| HAPAG poster for the West Coast of South America service. |

Of all their ships, one that would prove its longest surviving, hardly figured in the history of Germany's oldest overseas shipping company. Founded in 1847, the Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG), or as known in English, Hamburg American Line, was, at their height, before the First World War, the world largest shipping company. HAPAG were, with rival Norddeutscher Lloyd, the very symbol of German supremacy on the world's ocean highways, even to the exclusion of their British rivals.

Although famous for the Blue Riband record breaker, Deutschland of 1900, the first purpose-built cruise ship Prinzessin Victoria Luise of 1901 and the giant 52,000-grt Imperator, Vaterland and Bismarck of 1912-14, HAPAG made their real profits on the carriage of immigrants to America and cargo to much of the world, especially the Americas. Much of their remarkable expansion, innovation and market dominance was owed to its Director, Albert Ballin, who before the war, practically created modern passenger shipping from the luxury market to the humblest steerage traffic not to mention inventing the modern ocean cruise.

|

| The acquisition of the Kosmos Line in 1926 saw HAPAG expand their services to the West Coast of South America. |

The First World War and the Armistice of November 1918 claimed almost the entire fleet and Albert Ballin who, seeing a life's achievement destroyed, took an overdose of sleeping pills on the 8th. The Company, however, managed a remarkable post-war rebuilding and in 1926 HAPAG acquired the Deutsch-Austral & Kosmos Linien, their 60-ship fleet and routes, including those from Hamburg to the West Coast of South America. The Depression blunted further expansion and forced co-operation between HAPAG and North German Line that pooled costs, profits and losses.

|

| Route map, 1930, for the HAPAG-Kosmos West Coast of South America service. Credit: timetableimages.com |

From a fleet of 173 vessels totalling 1,100,000 tons in 1933 to 98 aggregating 714,000 tons in 1936, reflected effects of the Depression shipping slump, the policies of the National Socialist government and, in measure, international boycotts of German lines against the regime. The existing union between HAPAG and NDL which dated from 1930 was reformed and loosened in 1935 and government intervention to reduce HAPAG's debts by spinning off many of its regional operations saw the South American East Coast, African and Mediterranean routes reassigned to other German lines. In return, HAPAG gained exclusive rights to the West Coast of South America as well as the North Pacific via Panama routes.

In return, too, for government intervention to reduce their debts, HAPAG, too, found their ships used increasingly for political purposes and, notoriously, had to consent to Nazi demands that their popular New York liner Albert Ballin, named in honour of its greatest Director, be renamed Hansa as Ballin was Jewish and the sad saga of St. Louis is well known. In the wake of it all, came an astonishing output of some of the most innovative passenger vessels of their era, all of which had commercial careers measured in months, products of The New Order that would be thrown asunder with much of the rest of the world.

|

| HAPAG brochure, printed in February 1939, for the West Coast of South America service. Credit: eBay auction. |

The smaller, leaner HAPAG set about to modernise its fleet and in particular the West Coast of South America run so that within three years, the Hamburg-Valparaiso route was one of the real showcases of the German merchant marine, reflecting increasing German economic and political influences in the Americas, and eventually served, albeit fleetingly, by three outstanding new combination or "combi" cargo-passengers-- Monserrate (b. 1938/5,578 grt), Osorno and Huascaran (b.1938-39/6,951 grt) and one express luxury liner, the 16,595 grt Patria of 1938.

|

| Credit: Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 1 June 1937. |

On the occasion of HAPAG's 90th anniversary on 28 May 1937, Chairman of the Board Dr. Walter Hoffmann announced a new shipbuilding programme to include a new ship for the Eastern Asia route, three cargo ships of 4,500-get, two cargo cargo ships of 6,300 tons each and a ship of 5,600 with limited number of passengers. Of the two 6,300-ton cargo ships, these were contracted with Blohm & Voss's Hamburg yards and laid down as nos. 517 and 518. In due course, it was announced that no. 517 would be named Osorno after the volcano in Chile and no. 518 would be christened Huascaran after the mountain in Peru.

These were the most modern and technically advanced "combi" ships in the world at the time as well as the most luxurious in terms of passenger accommodation and facilities. They were miniature Patria's in their basic design, machinery and decor, and the three representing a heyday, albeit it a very fleeting one, for German shipbuilding and design without equal in the world.

|

| The pioneering HAPAG Wuppertal of 1936, the world's first ocean going diesel-electric merchantman, arriving at Melbourne. Credit: Allan C. Green Collection, State Library of Victoria. |

Today, when diesel-electric propulsion is common for the world's largest cruise ships (having been re-introduced to passenger ships with the re-engining of Queen Elizabeth 2 in Germany in 1987), it is worth recalling that it was pioneered by Germany and HAPAG in particular.

The first newbuilding of the reformed HAPAG, the 6,736-ton Wuppertal, delivered on 26 November 1936 by Deutsche Werft, Hamburg, was the world's first large diesel-electric ocean going vessel. But the basics of diesel-electric propulsion dates back to 1902 with the development of the German Navy unterseeboots or U-Boats. In merchantmen, the propulsion system offered maximum efficiency in output and fuel consumption as well as allowing individual diesels to be put "offline" for underway maintenance. The system also was exceptionally quiet running and vibration free, two qualities especially desired in passenger vessels.

|

| The magnificent Patria of 1938, first twin-screw diesel-electric liner of which Osorno and Huascaran were vest pocket versions. Credit: cruisebe.com |

Wuppertal, despite her conventional appearance, was one of the great pacesetters in pre-war marine engineering and so successful in service, that the propulsion system was carried over in the next four newbuildings for HAPAG launched in 1938: the imposing twin-screw 16,595-ton Patria followed by Osorno and Huascaran and, for the Far East run, the 8,736-ton Steirmark which became famous as the raider Komoran in the Second World War. Literally the last word in diesel-electric liners for many years was the 27,288-ton Robert Ley, completed in March 1939 for the NC Gemeinschaft Kraft durch Freude (KdF) organisation for German workers cruises and managed by HAPAG.

All these elektroschiffen had essentially the same machinery layout consisting of MAN-built diesels powering Siemens-built electric AC generators and propulsion motors and truly groundbreaking for the era, anticipating what is standard in many ships today. In Osorno and Huascaran, this consisted of three MAN (Augsburg) diesel engines-- two 2-stroke 8-cylinders and one 2-stroke 6-cylinder developing a total of 6,350 hp-- each turning a Siemens 2000 kva 3750 v. alternator at 244 rpm and driving a propulsion motor rated at 7070 hp at 122 rpm operating on 3750 v. current and driving a single screw. The maximum speed was 16 knots with a service speed of 15.5 knots. Fuel consumption worked out to about 30 tons of diesel fuel a day with a 1,098-ton bunker capacity.

Huascaran measured 464.7 ft. (overall), 459 ft. (b.p.), 60 ft. beam with a tonnage of 6,951 (gross) and 4,026 (nett) with five decks: Bridge, Boat, Promenade, Shelter and Main.

With six holds, three forward and three aft with a total capacity of 555,000 cu. ft. (bale) and 15,706 cu. feet (reefer) with a 8,860 deadweight ton capacity worked by four sets of substantial kingposts and mast booms and 20 electrically driven winches. It was claimed these were the most efficient cargo vessels in world, two teams of longshoremen being able to work simultaneously in 4 of the 6 hatches and reducing cargo working time in port.

|

| Interiors of Osorno (Huascaran was identical): Dining Saloon (top left), Smoking Room (bottom left), cabin (top right) and Lounge (bottom right). Credit: eBay auction photograph. |

Although limited to 35 berths (58 using uppers), all First Class, the passenger accommodation was exceptional with 18 all outside cabins with lower beds and running hot and cold water in all cabins, some also having private bathrooms attached. The public rooms were remarkably extensive for a "combi" type ship with a single-sitting dining saloon, lounge and bar-smoking room. The ample open, covered and glass-enclosed promenade space was capped by an outdoor pool on Sun Deck aft of the funnel. Her officers and crew numbered 58.

|

| Showing her beautifully modelled bows, three forward holds and characteristic Blohm & Voss kingposts. Credit: www.arbeitskreis-historischer-schiffbau.de |

The hull design of these ships was as advanced as their machinery, building on the German innovation of incorporating the Taylor (named after the American naval architect David W. Taylor) bulbous bow, rounded cast stems and hollow shaped waterline to reduce drag and provide a clean entry in express passenger liners in 1929, NDL's Bremen and Europa. This design was later used in the rebuilding of HAPAG's Albert Ballin-quartet in 1933 which reduced the required propulsion power by 28 per cent to maintain their 19-knot service speed. Blohm & Voss then introduced the concept to the new generation of German liners of the late 'thirties, Norddeutscher Lloyd Potsdam, Deutsche Ost-Afrika Linie's Pretoria and Windhuk. The final ships so designed were Osorno and Huascaran where it did not materially lessen wave resistance at their comparatively slow service speed but improved their seakeeping behaviour.

In appearance, Osorno and Huascaran were models of late thirties design and style with their sweeping, flared and rounded bows, high freeboard forward, solid but compact superstructures and stubby motorship funnels and especially their distinctive lofty, narrowly spaced kingposts with ventilator caps, ending in a gracefully profiled cruiser stern.

|

| A reminder that Osorno, destined for the sultry West Coast of South America, made her maiden voyage in a north German winter, January 1939. |

Osorno, launched on 7 September 1938 was completed in remarkably short order, being handed over on 21 December and making her maiden voyage on 6 January 1939.

|

| A beautiful portrait of Osorno showing the pleasing combination of purposefulness and proportion of these sisters. Credit: www.maritime-photographie.de-Wolfgang K. Reich-Wedel. |

For a vessel that would endure for a remarkable 59 years, Huascaran was ordered, built, launched and delivered just as quickly as her sister. Ordered in May 1937, she was launched on 15 December 1938 and handed over on 27 April 1939, so just under two years from contract to completion.

|

| Beginning her remarkable 59-year career, Huascaran leaves the Blohm & Voss yards, Hamburg, in April 1939. |

Berlin, May 11--

Considerable interest has been aroused here by Field Marshal Herman Goering's 'private cruise' in the Mediterranean aboard the new Hamburg-America Line's new motorship Huascaran on her maiden voyage. Press reports had said that the Marshal was going to Valencia, which rise to speculation as to whether he might not be going there in an effort to persuade Spain to join the Italo-German military alliance.

An official report here today said that Marshal Goering in connection with his visit to San Remo, Italy, had accepted a long-standing invitation from the steamship line to make a trip on the Huascaran in the Mediterranean. He is aboard, the report continued, cruising along the western shores of the Mediterranean, and 'at the conclusion of his trip in a few days will return to Berlin from an Italian port."

Montreal Gazette, 12 May 1939

Huascaran's entry into service thrust her into headlines in a way that would only be repeated once for the rest of her 59-year career. She came on the scene during a time of unmitigated triumph for Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in March 1939 with German forces occupying Czechoslovakia and the victory of Franco's Nationalist forces in the long Spanish Civil War. Amid plans for a triumphant return of Germany's Condor Legion which had fought with the Nationalists from Spain by ship and rumours that Franco would join Spain to the German-Italy Axis, HAPAG dispatched Huascaran on a "trials cruise" from Hamburg to Genova, thence on a Mediterranean cruise that would accommodate one "V.I.P."

Field-Marshal Goring has accepted an invitation from the Hamburg-Amerika Line to take part in the maiden voyage of the Huascaran in the Mediterranean.

Official communique, 11 May 1939.

The new HAPAG ship was sailing right into the middle of an extraordinary power struggle between Reichmarshal Hermann Göring and Foreign Secretary Joachim von Ribbentrop. Without informing the German ambassador in Spain or the Foreign Office in Berlin, Göring made plans to meet with Franco in Spain during a many months long Mediterranean vacation he was enjoying (which had already included a visit to Libya aboard the HAPAG liner Monserrat on 7 April from Naples to Tripoli as a guest of Governor Italo Balbo). At first Franco consented to the meeting, then dithered over where it should be held, preferring Saragossa while Göring insisted on Valencia.

Sailing from Hamburg on 29 April 1939, Huascaran passed Gibraltar on the 30th, bound it was said for Alexandria. On 9 May, amid enormous international press attention, Göring embarked on the vessel at San Remo, sailing out of the harbour escorted by the German destroyers Friedrich Ihn (Z14) and Erich Steinbrinck (Z15) and the supply ship Altmark. By the time he reached the Spanish coast, Foreign Minister Ribbentrop called off the meeting and Hitler sent Göring a message at sea forbidding him to land and sail back to Italy. It was then that Göring's office concocted the ruse that he had been "invited" by HAPAG to "take part in the maiden voyage of the Huascaran in the Mediterranean," as part of his holiday. Returning to Livorno on the 12th, where the deeply humiliated Reichmarshal disembarked, and returned Berlin in a few days. Meanwhile, Huascaran returned to Hamburg, passing through the Straits of Gibraltar on the 15th and arriving at her homeport on the 18th.

|

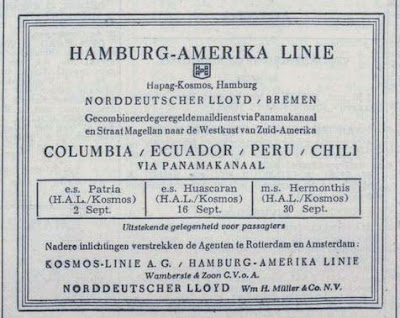

| HAPAG advertisement showing the maiden voyage of Huascaran from Hamburg as 3 June 1939, in the event, she sailed on the 1st. Note, also, the misspelling of the nation of Colombia as "Columbia"! |

As Huascaran prepared for her maiden voyage on her regular route to Valparaiso, the Pact of Steel between Germany and Italy was signed in Berlin on 22 May 1939 and the Port of Hamburg was the scene of a triumphant return on the 30th of the Condor Legion aboard Wilhelm Gustloff, Robert Ley, Der Deutsche, Stuttgart, Sierra Cordova and the Oceana escorted by Admiral Graf Spee and Admiral Scheer and passing in review of Reichmarshal Göring aboard the State Yacht Hamburg.

|

| E.S. Huascaran heads out to sea to commence a commercial career for HAPAG that lasted but four months but just the beginning of a 59-year lifespan for a remarkable vessel. Credit: shipsnostalgia.com |

Huascaran with doubtless rather less fanfare, sailed from a crowded Port of Hamburg on 1 June 1939, but her departure was no less noteworthy, being the last new German liner to enter service before the outbreak of war. As it was, she was embarking on her one and only commercial voyage.

|

| HAPAG's West Coast of South America route and fleet in 1939 at its short-lived apogee on the eve of war: Patria, Osorno, Huascaran, Monseratte, Hermonthis and Rhakotis. Credit: eBay auction photo. |

The normal route for the HAPAG West Coast of South America route was Hamburg to Cherbourg, Southampton, Kingston (Jamaica), Panama Canal, Buanaventura (Colombia), Salinas (Guayaquil), Callao (Peru), Mollendo (Peru), Arica (Chile), Antofagasta (Chile) and turning around at Valparaiso, Chile, a distance of some 9,981 sea miles, and calling at the same ports homewards.

On her first (and only) voyage, Huascaran seems to have skipped her calls at Cherbourg and Southampton and recorded to have passed the Azores on 12 June 1939, transited the Panama Canal 21-23, called at Salinas on the 27th and arrived at Valparaiso on 9 July. Homewards, she made two extra calls, one at Corral (Chile) 17-18th and Talcahuano (Chile) on the 22nd, in addition to the regular waystops, including Callao on 3 August, another extra call at Salaverry (Peru) on the 6th, passing through the Panama Canal 9-10th and, skipping Cherbourg and Southampton (the news of the signing of the Germany-USSR Non-Aggression Pact in the middle of the night of the 23rd-24th guaranteeing the eminent outbreak of war), Huascaran arrived at Hamburg on the 25th, ending a 20,000-mile maiden voyage and her commercial career.

|

| HAPAG advertisement showing Huascaran's planned second voyage for the West Coast of South America scheduled to depart Hamburg on 16 September 1939. |

Huascarn's next voyage, scheduled to depart Hamburg on 16 September 1939 was obviously cancelled upon the German invasion of Poland on the first of the month and Britain and France declaring war three days later. Her one voyage commercial career as a HAPAG liner was unquestionably the shortest chapter in her 59-year history and the brand new Huascaran was now, with so much of the world, to go to war.

|

| E.S. Huascaran, the world's newest and finest combination cargo-passenger liner, April-September 1939. Credit: shipsnostalgia.org |

So the new Huascaran, "enlisted" in the Kreigsmarine. In the seeming prosaic and unheroic role as a werkstattschiff which, as so happened that put the ship and her crew at the heart of German naval operations in occupied Norway. From 1940-45, Huascaran rendered vital repair and support work to some of the most famous ships of the German Navy.

1939-1945

On 11 November 1939 Huascaran was commissioned as Werkstattschiff 1 after having been converted to the purpose of a repair ship for the navy, both for surface warships and submarines. This entailed added a boxy superstructure extension aft of the funnel in place of the open deck space for extra accommodation, fitting her with extensive machine shop facilities including a forge (for which a prominent kingpost smokestack was fitted directly behind the superstructure addition), in the 'tween deck which was further provided with portholes, the work being done by HAPAG repair works in Hamburg.

|

| Huascaran, after her aft superstructure had been extended, but still in mostly peacetime livery, at Pillau, East Prussia c. 1940. |

The invasion of Norway and subsequent occupation of France in April-June 1940 finally gave the German Navy what had always eluded it: bases directly on the Atlantic and Channel coasts. With the u-boat fleet based from L'Orient and Brest on the French coast, a major base for heavy surface units was established in the Lofjord, north of Trondheim, where they could be serviced and repaired, without being "bottled up" in the North Sea bases at Kiel and Wilhelmshaven. In her role as a repair ship, Huascaran performed a critical function in the new base's operation and had a very busy war without barely going to sea.

On 1 June 1940 Huascaran left Kiel and indeed Germany "for the duration," destined for Trondheim and carrying ammunition, in company with Alstertor and Samland and escorted by four M-boats, three R-boats and Elbe, arriving on 6 June.

|

| Huascaran alongside the damaged German battleship Gneisenau in Lofjord, June 1940. Credit: Kriegsmarine Facebook group. |

Huascaran's repair crews were very soon called to their tasks when the Royal Navy, in two separate engagements, damaged the sister German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. After being hit in the stern by a torpedo attack by the British destroyer H.M.S. Acasta, Scharnhorst took refuge in the Lofjord from 9-20 June 1940 where she repaired by crews of Huascaran and Parat before sailing to Kiel. On the 20th, Gneisenau was hit on the starboard bow by a torpedo by the British submarine H.M.S. Clyde and she, too, underwent provisional repairs in Lofjord by Huascaran's technicians before retiring to Kiel on 25 July.

|

| Prinz Eugen (centre) under repair in the Lofjord; next to her, on her starboard side, is the repair ship Huascaran; Admiral Scheer is also moored behind anti-torpedo nets. Credit: Wikipedia Commons. |

The ship's most impressive repair job was on the famous heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen which, after being torpedoed off the Norwegian coast by the British submarine H.M.S. Trident on 23 February 1942 which blew off her stern, managed to make to Trondheim and then towed to Lofjord where she arrived on the 25th. There, Huascaran's repair crews, with great skill and ingenuity, cut away the remains of her entire stern, plate over the hull end and fit two jury-rigged rudders, operated by capstans and cables. On 16 May Prinz Eugen managed to sail for Kiel for complete repairs.

On 31 July 1943 Huascaran left Trondheim for Altafjord, escorted by destroyer Z-29, and arrived, via Narvik, on 3 August to join the support ships for the battleship Tirpitz moored there.

After repeated attacks, the Royal Air Force finally succeeding in destroying the battleship Tirpitz off Håkøy Island near Tromsø, Norway, on 12 November 1944 and Huascaran went alongside the capsized wreck to rescue trapped survivors in the hull. After this, she returned to Lofjord to act as a support ship for the 13th U-boat Flotilla based there.

|

| Sonderführer Kapitänleutnant (Ing.) Jacob Koepke (1900-1965), workshop manager of Huascaran, 1940-45. Credit: https://forum.axishistory.com/ |

The workshop manager aboard Huascaran since 19 April 1940, Sonderführer Kapitänleutnant (Ing.) Capt. Lt. Jacob Koepke, was awarded the Knight's Cross with Swords of the Order of War on 28 January 1945.

Just a few days before the German surrender on 7 May 1945, the U-boats of the 13th Flotilla completed their final wartime patrol and returned to Narvik to join Huascaran and the fleet tender (and Hitler's former yacht) Grille there among the other support vessels. On the 12th, the allies ordered all German naval units in the Narvik zone to sail to Skjomenfjord. Instead, three days later the depot ships Huascaran, Stella Polaris, Grille, minesweeper Kamerun and the fleet tanker Kärnten along with 15 U-boats departed for Trondheim, but were intercepted on the 15th by the Royal Navy's 9th escort group off Åsenfjord. Among those diverted from escorting convoy JW67 to Murmansk to intercept the Germans was the Canadian Navy's River-class frigate (built by Vicker Canada, Montreal) H.M.C.S. Matane (K-444) whose Captain, Lt. J.J. Coates, RCNVR, took the surrender of the German vessels from Capt. Reinhard Suhren aboard Grille on the 17th.

The 15 U-boats were escorted to Scotland by Matane and other units whilst Huascaran and the other surface vessels proceeded to Trondheim. There, Huascaran was formally seized by the British, her 13 officers, 50 Petty Officers and 280 ratings were taken prisoner and the German patrol boats V6602, V6603 and V6605 moored alongside. She was eventually laid up in the Lofjord awaiting deposition as a prize of war.

On 14 November 1945 Huascaran, then at Liverpool, was handed over to Canada by the War Reparations Commission. Although managed by the Park Steamship Co.. Montreal, which operated Canada's government owned, wartime-built standard ships, there is no evidence that Huascaran was used in their service and appears to have remained in lay-up, eventually in the Clyde off Greenock.

Just over six years old, Huascaran had lost her homeland, line and intended service and was in the hands of strangers. As such, she had much in common with millions in Europe and elsewhere in the aftermath of the war and the remaking of the Continent.

Her dull war paint, scraggy and rusted now, makes the once proud unit of the Hamburg-America line look something of a bedraggled old lady, tied up at her Sorel wharf.

But the rebuilding job will change all that. Tuesday in the Commons, Reconstruction Minister Howe made known then that the 6,900-ton liner which Canada took as part of war reparations from Germany, was being prepared for immigrant use.

Edmonton Journal, 10 July 1947

It was with a certain irony that a now "homeless" ship, torn from her normal commercial life, country, officers and crew, should find a new career, country and crew in the carriage of passengers who, too, had lost home, homeland and happiness, to a new beginning.

1947

No other steamship company of an allied country suffered proportionally as heavy losses in the Second World War than Canadian Pacific with five Empresses, two Duchesses, all the Monts, all the Beavers lost to the fleet by the end of 1945 through enemy action, maritime accident and one to a fire whilst being refitted and one to extended transport service. The road back was long and slow, and included a bit of detour when the company found itself acquiring a very different sort of vessel for a new service that reflected a post-war world that was no less fraught with problems.

|

| Initial sales announcement for Huascaran and Empire Gatehouse. Credit: 15 January 1947. |

On 19 January 1947 Park Steamships Co. Ltd, acting as agent of Canada's War Assets Corp. offered two German-built ships that been award the Dominion by the Inter-Allied Reparations Agency: the steamer Empire Gatehouse, at Halifax, and Huascaran, then anchored off Greenock. Both were offered under the proviso they would be operated under Canadian register and, additionally, it was stipulated that Huascaran be reconditioned and repaired in Canada, with tenders to be submitted by 29 January. Clarke Steamship Co. bought Empire Gatehouse but sale of Huascaran was not immediate and she was offered independently with tenders to be submitted by 17 February, this time specifying a minimum bid of $606,000 for the vessel.

|

| When offered for sale separately, a minimum bid of $606,000 for Huascaran was specified. |

Huascaran was sold to North American Transports Ltd., of Montreal, on 19 February 1947, War Assets Corp. holding a $465,000 mortgage on the vessel.

The orphaned Huascaran now found a new home, of sorts, if not an immediate or disclosed purpose. That she would eventually find employment taking tens of thousands to their new homes, indeed country, seemed entirely fitting.

|

| Credit: columbiabasinherald.com |

Of the welter of acronyms produced by "WW2" which was the most famous of all, among the more sadly common in the wake of it was the "DP" or "Displaced Person," the bureaucratic shorthand for the human tragedy of 40 millions who had lost their homes and, in many cases, their countries after the war, both by the actual combat and forced dislocation during the period 1939-45, and by the post-war reordering of European boundries, governments and the evolving Cold War and Soviet Occupation. Of these, no fewer than 11 million were in Allied Occupied Germany, including former POWs, slave laborers, concentration camp survivors, orphans, Poles, Ukrainians and ethnic Germans forcibly removed from East Prussia, Danzig, Sudetenland, Silesia, Poland and the Baltic States as well as those fleeing Russian occupied East Germany. The ethnic cleansing that characterised the Third Reich, was no less a feature of the remaking of post-war Europe, both contributing to the DP crisis.

Even after some six million refugees had been repatriated, the remaining "DPs", many with no place to go, were housed in improvised camps. Gradually, many counties all over the world began to accept them as immigrants whose immediate needs were entrusted to more acronyms, the UNRRA, the United Nationals Relief and Rehabilitation Administration and IRO or International Relief Organisation. Notable, too, were the number of charitable and religious organisations that had enormous impact on finding new homes and lives for DP's throughout the world especially those excluded, on political grounds by the USSR, from IRO aid and relocation, as the evolving Cold War cast its shadow on those already dislocated by the real one just ended.

Canada was, with Belgium and Great Britain, among the first countries to adopt a settlement scheme for DPs. It was, of course, a nation already built on immigration, a vast but underpopulated land of but 3.4 millions at Confederation in 1867 that had by the end of the First World War grown to 8.3 millions and by end of the Second World War, 12 millions, the vast majority of immigrants originating from the British Isles and most of it under government schemes to encourage settlement of the prairies and the West. Of European immigration to Canada, Germans played an early part, burgeoning during the American War of Independence (Samuel Cunard's family were German-Americans who as Loyalists settled in Halifax) and another substantive wave were Mennonites and Hutterites from America and between the world wars, some 100,000 Germans immigrated to Canada.

The passing of an order-in-council in Ottawa on 6 June 1947 for the immediate admission to Canada of 5,000 DPs, was prompted by an outcry against "commercial immigration" after a private Canadian businessman sponsored 800 Poles to work for his company. But the government scheme, too, was built around a preferred low-skilled employment qualification to ease chronic labour shortages in mining, logging, agriculture, textile trade and domestic service. Canada also signed an agreement with the Dutch government to bring in agricultural families. Between 1947 and 1949, close to 16,000 individuals from Dutch farm families resettled in Canada and by 1954, 94,000 Dutch immigrants came to Canada between 1947 and 1954.

Excluded from IRO assistance (at the insistence of the USSR), however, were the so-called Volksdeutsche, the ethnic Germans forcibly removed from East Prussia, Danzig, Sudetenland, Silesia, Poland and the Baltic States as well as those fleeing Russian occupied East Germany, estimated at some 12 millions. Their plight, worsened by increasing tensions between the West and the Soviet Union in a divided Germany, attracted the attention of the considerable German community in Canada, centered on its churches.

|

| Dr. T.O.F. Herzer (1887-1958). Credit: Canadian Lutheran World Relief, https://www.clwr.org |

One of the greatest champions of German immigration to Canada was Dr. T.O.F. Herzer, a trained Lutheran pastor and General Manager of the Canada Colonization Association (a division of the Canadian Pacific Railway), who facilitated the emigration of thousands of Mennonites from Russia to Canada in the 1920s. After the war, he was a leader of the Canadian Lutheran World Relief (CLWR) and helped establish in Ottawa in June 1947 the Canadian Christian Council for the Resettlement of Refugees (CCCRR) in co-operation with The Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization, Canadian Lutheran World Relief, the German Baptist Union, and the Catholic Immigration Aid Society, This organisation undertook a comprehensive sponsorship of some 15,000 Volksdeutsche and 6,500 Mennonites not qualifying for IRO assistance.

Availing of Canada's prioritising non IRO sponsored immigrants to "immediate family members" of those already residing in the country, German-Canadians sent in applications to sponsor 20,000 and the Canadian Government in August, working with the British and American occupation authorities in the western zones of Germany, agreed to the CCCRR facilitating the processing, vetting and transportation of these individuals from Bremen to Canada.

|

| Credit: The Windsor Star, 16 August 1947 |

In November 1947 the CCCRR was recognised as an agent of the Canadian Government to facilitate the immigration of qualified Germans to Canada, the first country to do so after the war. Even so, Germans were still classified as enemy aliens until September 1950 and applicants who had served in the Germany Army or had been members of the NDSAP were not eligible. Even so, an estimated 1,500 Nazi war criminals and collaborators were able to enter Canada between 1947-51, including the notorious Helmut Rauca, owing to inadequate security screening. It was a tiny minority among the 157,000 DP's,15,000 Volkdeutsche, 6,500 Mennonites who came over by 1950 and then with the readmission of German nationals (Reichdeutsche), another 250,000 Germans from 1950-1960 came to Canada.

Now all that was needed were the ships. Canadian authorities quickly discovered that of the approximately 50 passenger liners being operated on account of the British Ministry of Transport as troopships none was available for the transport of immigrants. Much of this was due to the British decision to withdraw occupation forces in Europe and overseas, extending troopship charters. Filling the gap in immigrant berths, for the timebeing, were IRO-chartered American troopships, but the shortage of tonnage severely crimped Canada's desire to increase immigration.

Rather than being entirely dependent on the Americans and the British for tonnage, integral to Canada's initial post-war immigration plans was a dedicated Canadian vessel for both IRO sponsored DPs and the CCCRR sponsored immigrants. Indeed in making the first announcement of the immigration of DPs, Reconstruction Minister Rt. Hon. C.D. Howe said "the government hopes to a convert a vessel obtained from Germany as part of war reparations to carry the immigrants." That was in July 1947 following acquisition of Huascaran and her subsequent arrival in Canada.

|

| Huascaran at Liverpool on 26 April 1947 undergoing engine repairs before setting off for Canada. Credit: Liverpool Maritime Museum. |

After a general overhaul at Liverpool commencing in April 1947, Huascaran, under Capt. Geo. L. Hayes and a crew of 23, including one of her original crew, Second Engineer Rudolph Rolph, sailed in June for Canada, arriving at the Marine Industries' shipyard at Sorel, P.Q. on the 26th after a uneventful voyage, the first extended one for the vessel since her maiden trip back in June 1939. She was surveyed by the Montreal naval architect firm of German & Milne (which recently designed the "world's most modern icebeaker," the ferry Abegweit) and found to be suitable for conversion into a high capacity immigrant vessel which could be used as such westbound yet be readily converted to a full cargo vessel eastbound. Over 100 workers were tasked with the conversion.

All of this went initially unreported in the press and it was not revealed, rather casually, until the following month when Huascaran was specifically referenced in Ottawa by Reconstruction Minister Howe when announcing passage of an order-in-council to allow immediate admittance of 5,000 displaced persons to Canada. The Gazette on 5 July 1947 reported that:

...it was learned that the vessel has been sold to a Quebec firm and recently crossed the Atlantic to Sorel where she may be fitted out as an immigrant ship which could transfer 500 or more persons a voyage. Negotiations now are proceeding between Government authorities and the shipping interests which have acquired the vessel for a working arrangement to engage her for transfer of immigrants unable to cross to Canada because of the tight Atlantic shipping situation." On the 7th in the Commons, Minister Howe, in reply to a question, stated the ship had been turned over to Canada as reparations in a damaged condition in a German harbour and as Canada had no convenient means of getting her to the country, she was turned over to war assets for sale, "the ship was purchased by a Canadian firm, and repaired in Germany, then moved to Britain for further repaints, has now been delivered to Canada. The ship has been surveyed and found capable of carrying 600 immigrants. The survey was made at request of the present owners, who propose to convert the ship at their own expense.

The final part of the puzzle was put into place in August 1947 when Canadian Pacific, the company that had practically invented, refined and was made for the populating of the Dominion with immigrants, purchased Huascaran from North American Transports after the Canadian Government and Canadian Pacific came to an agreement that if the line would operate the vessel for at least three years in the movement of refugees, the government would pay half of the anticipated $600,000 needed to refit Huascaran for passenger service.

The company, as a major step, has purchased the former German liner, Huascaran. The conversion of this ship, to enable her to carry eight hundred immigrants to this country each trip, will be of material assistance in easing the immigration bottleneck. The Huascaran, renamed the Beaverbrae, will be in service early in the new year.

Canadian Pacific Annual Report, 1947

The need for a sound immigration flow to Canada was never more apparent. This county, from one to the other, on the new frontier of the northwest, is in desperate need of the same kind of manpower which pressed its development in the early years of this century.

Western Canada in particular has entered a new stage of postwar expansion which will unquestionably be reflected to a major degree throughout the while economic structure of the Dominion."

W.M. Neal, CBE, Canadian Pacific Chairman and President

4 September 1947 in Montreal

In Montreal on 2 September 1947, Canadian Pacific Railway Co. purchased Huascaran from North American Transports Co.. After returning from a month's inspection tour of Western Canada and the North West Territories, Canadian Pacific Chairman and President W.M. Neal announced in Montreal two days later the acquisition of Huascaran which was "to enter immigrant passenger service on the Atlantic service during the coming winter. The ship will provide space for approximately 700 persons, each voyage, plus a considerable cargo capacity." (Ottawa Citizen, 5 September 1947). Mr. Neal, in his announcement, added: "Operation of the Huascaran, as the other ships which the Canadian Pacific now owns or may acquire, will be proceeded with in closest co-operation with the Dominion Government as the nation's immigration policies develop...We must open the doors wider, to let in more new Canadians, for it is only by sharing the opportunity that we ourselves may reap the fullest benefit."

Huascaran was renamed Beaverbrae (II) on 25 September 1947, the name honouring one of the five-strong Beaver-class cargo ships, all lost during the war, and this was announced five days later by W.M. Neal, sailing from Montreal in Empress of Canada. The name also reflected the ship's dual purpose role, joining the post-war Beaver-class ships on the cargo run to Britain eastbound, a function no less essential than her westbound immigrant-carrying crossings.

The Canadian Pacific cargoliner Beaverdell, en route to Montreal from London, stopped in the St. Lawrence off Sorel on 30 October 1947 to unload a consignment of 16 British-built lifeboats for the refitting of Beaverbrae.

|

| A smart looking Beaverbrae poses at Sorel, P.Q. for her official Canadian Pacific photo even if none of her additional davits and lifeboats have yet to be installed. |

|

| Registered in Montreal, Beaverbrae proudly flew Canada's "Red Duster" and was the largest deep-sea Canadian registered merchantman. |

Beaverbrae was entered in the Canadian Register on 27 November 1947, registered in Montreal and, at 9,033 gross tons, the largest Canadian-flagged deep sea vessel and the first Canadian registered trans-Atlantic liner since CNR's Royal George and Royal Edward of 1910.

|

| Capt. G.O. Baugh, OBE, RD, RCNR (Ret'd). |

At the same time, her master was appointed, Capt. Gerald Ormsby Baugh, OBE, RD, RCNR (Ret'd), laterly Staff Captain of Empress of Scotland. Born in Birmingham, Capt. Baugh joined Canadian Pacific in 1931 as a junior officer in the same ship, then named Empress of Japan. Moving to Vancouver, he served in the Royal Canadian Navy during the war, commanding H.M.C.S. Alberni, the first corvette built at Victoria, B.C. and then commanding the destroyer H.M.C.S. St. Clair for two years in the Battle of the Atlantic. When he settled aboard Beaverbrae at Sorel, he discovered the flag of German Rear-Admiral Felix von Huntzmann in a locker aboard and kept it as a ironic souvenir for a veteran of the Battle of the Atlantic now commanding a former unit of the German Navy.

In place of the faded colors of Rear-Admiral Felix von Huntzmann, which she was flying when she was captured, her new colors will be Canada's 'Red Duster' and the checkered houseflag of Canadian Pacific Steamships.

The Vancouver Sun, 11 December 1947

Before the St. Lawrence was closed to navigation for the winter, Beaverbrae left Sorel on 6 December 1947 for Saint John, N.B. for completion of her refitting work there.

|

| Beaverbrae alongside the Marine Industries shipyard at Sorel. Credit: National Post, 14 February 1948. |

Second only to the conversion of the Donaldson liner Letitia into a hospital ship by Vickers Canada, Montreal, during the war, the transformation of Huascaran into the emigrant liner Beaverbrae at Marine Industries' Sorel, P.Q., yards was the biggest project of its kind undertaken in a Quebec shipyard.

It was, however, hardly uncommon just a few years after the end of the war, to convert ships to new roles, even unlikely ones nor to adopt a ship that once had 38 berths to have some 750 and to do so in short order. The result was a vessel unlike any another in Canadian Pacific history and an unusual if somehow also fitting ship to be the largest in the Canadian Merchant Navy at the time. Neither Empress nor Duchess, not even a Mont, she was a Beaver, essentially a freighter whose westbound cargo was 780 men, women and children for which there were no brochures, deck plans or alluring posters.

In many essentials, Huascaran remained unchanged: her cargo spaces and handling gear, her machinery, dimensions and even her basic appearance. She was, after all, not even ten years old when she embarked on the latest chapter of a long, long career that would see her undergo far more drastic makeovers. Externally, the biggest change, other than the unattractive two-storey "box" added to her after superstructure dating from her conversion as a naval workshop ship, was a considerable augmentation of her lifesaving equipment, reflecting her vastly increased compliment. From two lifeboats to 18 required two extra pairs of davits on each side her Boat Deck carrying eight lifeboats and another two pair on each side atop a new deck over her poop deckhouse carrying another eight.

Beaverbrae remained prodigious cargo carrier, her six holds had a 555,000 cu. ft. (bale) and 15,706 cu. ft. (reefer) and she retained Huascaran's efficient cargo handling gear.

In appearance, Beaverbrae was no graceful White Empress, and quite distinctive from other CP ships with her squat motorship funnel and boxy midships superstructure block and heavy narrow spaced kingposts that all contributed to businesslike profile that reflected her role. She did retain her beautifully long and flared bows so that that view from ahead, Beaverbrae looked quite pleasing.

|

| E.S. Huascaran as built, 1939. Credit: shipsnostalgia.com |

|

| A postcard view of Beaverbrae in placid seas that her passengers would but envy on their often rough passages, especially in winter, from Germany to Canada. |

The 9,034 grt Beaverbrae had 773 passenger berths making her Canadian Pacific's largest capacity passenger liner at the time (compared to Empress of Canada/Empress of France which carried 700), a distinction perhaps less appreciated by those sailing in her. She had five decks: Bridge, Boat, Promenade, Shelter and Main. The private cabin accommodation, for 74, was on Promenade Deck and reserved for women travelling with babies and children. The balance of 699 passengers were berthed in dormitories in the 'tween decks on Shelter Deck with men quartered forward and women aft in two tier bunks and married couples were separated. During the conversion, additional portholes were fitted along the length of this deck but fore and aft passageways, cut through the bulkheads were narrow and naval in character. Washrooms were adjacent and companionways led to the open decks through openings in the hatchcovers. Passengers were expected to make their own bunks and keep their quarters clean as well.

The public facilities were limited to a large dining/common room amidships on Shelter Deck with a piano and provision to show movies. That, and recorded music "concerts" constituted the extent of the entertainment. The enclosed promenade had deck chairs and open deck space on the fore and aft cargo decks. For a ship whose passenger list was usually one-fifth children, one of the major deficiencies was a complete lack of any playrooms or facilities for them. There was a small canteen for the purchase of toiletries and cigarettes.

"Hot and a lot of it," best described the food although the three meals a day was a luxury not experienced for many since 1939 with meat offered for breakfast, lunch and dinner although the novelty of American bacon was perhaps not relished by her often seasick passengers. Every voyage, the ship was provisioned with 10 tons of potatoes, 9 tons of fresh meat, 3 tons of smoked meat, 7 tons of pasta, 4 tons of vegetables, 2 tons of butter and cheese, 300 jars of baby food, 10 tons of sugar, 1 ton of jams, 16,000 chocolate bars and 36,000 bags of candy. It was not uncommon for passengers to enlist to work in the galley or serve as the ship's "police" in exchange for cigarettes or other luxuries.

Alas, for many, food was the last things on their minds for Beaverbrae was many things but a good seaboat was not among them. Light in displacement on the westbound crossings with no or little cargo, and with the extra tophamper of her added lifeboats, she could pitch and roll horribly and sailing year-round, the winter crossings could be miserable. Of all of the published accounts of voyages in her, seasickness is a common element, some of her unfortunate passengers were literally sick for the entire 10 or more days across.

In addition to her 116 officers and crew, Beaverbrae was staffed with an an IRO Escort Officer, Asst. Escort Officer, two stewardesses, a doctor, nurse, dispenser and hospital attendant.

Beaverbrae was indeed like no other Canadian Pacific ship, certainly utilitarian, a bit cobbled together but worth considering that she was only the third CP passenger ship in service when she made in her first voyage (following Empress of Canada and Empress of France) and was, in fact, the newest (by quite a margin) in the fleet, being 11 years newer than the two 1928-built Empresses being less than ten years old when recommissioned.

On 24 January 1948 details as to the settlement scheme were released. Of the 770 immigrants to be accommodated each westbound voyage, more than half were travelling under the auspices of the CCCRR and the remainder by the International Refugee Organization or IRO In a conference on 23 January 1948 of the Canadian Citizenship Council, R.L. Christopherson, Asst. Commissioner of the CPR's Department of Immigration and Colonization, said that only about about half of displaced persons in occupied countries were eligible under the IRO and it was these people, many anti-Communists or ethic Germans who had to flee their homes in Eastern Europe in advance of Soviet forces. A working team had been sent to Germany to assist in assembling prospective immigrants. Immigrants brought forward by the council had relatives in Canada to act as sponsors.

Altogether fitting for "The World's Greatest Transportation System," Canadian Pacific's Beaverbrae was not an individual ship, but rather one component in an intricate, carefully planned and integrated means of relocating peoples from one country to another via ship and trans-continental railway on one single through ticket and, in many cases, with their new home or farm or job pre-arranged as well. No one did it better or for longer, and no single company better suited to operate Canada's only dedicated immigrant ship. In addition. both CP and CNR had recent and extensive experience operating troop transport trains throughout the Dominion from the Eastern embarkation ports. If it was sometimes akin to "people processing" in character as well as quality, it was remarkably efficient so that once cleared for embarkation, a Beaverbrae passenger could be in his or her new Canadian home within three weeks of sailing, often a journey of some 5,000 or more miles for those destined for the west.

On the German side, however, the cue was taken from HAPAG and Albert Ballin's innovative Immigrant Village in Hamburg prior to World War One where immigrants were housed, fed, bathed and medically inspected prior to boarding HAPAG liners for New York, the motive not being so much charity but to ensure that all were accepted upon arrival in Ellis Island lest be they be deported at a loss to the company.

So it was that the CCCRR established a smaller version, in Bremen, the Bremer Uberseeheim, Auswanderung Nach Canada or the Bremen Overseas House for Emigration to Canada. Housed in two fine buildings, containing simple rooms for families and small dormitories for single men and women, cafeteria, dispensary, barbers, kindergarten and classrooms, laundry as well as the offices of the CCCRR, it was entirely organised to process 770 immigrants for Canada for each of the 8-10 one-crossings from Bremerhaven (later Bremen) to Canada. Many of the arrivals had barely enough clothing and this was augmented by a store of donated garments, shoes and luggage from Canadians all over the Dominion. Timed with the arrival of Beaverbrae, that voyage's allotment of immigrants received a final medical clearance and exchanged their old identity documents for Canadian documents and packed and ready to embark the following day. All this ensured a quick turnaround for the vessel outbound and pre clearance on arrival at Halifax, Saint John or Quebec.

.jpg) |

| Entrance to the Bremer Uberseeheim, the CCCRR refugee camp. Credit: Canadian Lutheran World Relief, https://www.clwr.org. |

|

| Left: family accommodation, Right: Canteen. Credit: Canadian Lutheran World Relief, https://www.clwr.org. |

|

| Left: camp doctor, Right: kindergarten. Credit: Canadian Lutheran World Relief, https://www.clwr.org. |

|

| Left: mess hall, Right: church. Credit: Canadian Lutheran World Relief, https://www.clwr.org. |

|

| Left: Exchanging old identity papers for Canadian passports, Right: Even the youngest immigrant had his or her papers. Credit: Canadian Lutheran World Relief, https://www.clwr.org. |

|

| Right: Saying farewell to the camp on embarkation day, Left: Going aboard Beaverbrae. Credit: Canadian Lutheran World Relief, https://www.clwr.org. |

|

| A final souvenir photo. Credit: Canadian Lutheran World Relief, https://www.clwr.org. |

On the "other side," Beaverbrae, arriving at Halifax or Saint John in winter or Quebec in summer, was met by two special Canadian Pacific or Canadian National trains. Every immigrant was "tagged" with the tag indicating his or her final destination in Canada. These trains, often 12-16 cars long, composed of the famous "colonist" austerity sleeping cars (day coaches with folding upper berths) which had been the "covered wagons" of Canadian emigration and settlement of the prairie provinces. Two passenger trains with baggage cars usually took the arrivals to Montreal and Toronto, or to Winnipeg and further western destinations, with virtually every car targeting a different area. Each train was provided with three special cars, a kitchen car and two dining cars, one of which served the train crew as a sleeping car at night. A Canadian Pacific press release detailed that one these Western trains was stocked with a ton of meat, a ton of vegetables, 300 pounds of fish, 250 dozen eggs, 125 pounds of butter, 75 gallons of milk and half a ton of bread.

|

| Dutch family boarding Canadian National special settler train upon arrival at Halifax. Credit: Canadian National Railway X32173 via Canadian Museum of Immigration. |

So after a 10-12 day sea voyage, it might be another four days before the somewhat bewildered settler, having seen much of the breadth of the Dominion en route, arrived at his new home. The trains often met by dozens of relatives, seeing family members for the first time or after a dozen or more years absence. The last link in the chain was complete and another 770 New Canadians were finally in their new home.

|

| Cover of brochure detailing CP's vital Beaver cargo ship service from Canada to Britain of which Beaverbrae was an integral part. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

Although Beaverbrae is best remembered for her refugee transport role, she was very much a "dual purpose" vessel from the onset and an integral member of Canadian Pacific's famous "Beaver" cargo service. Indeed, re-establishing this (the entire five-strong pre-war Beaver-class of cargoliners being lost in the war) took precedence over reviving the passenger service owing to the rather desperate state of Britain c. 1945-52 after "Lend Lease" shipments suddenly ended with peace, the country faced serious and sustained food and raw material shortages.

So it was that the very first post-war CP newbuilding was Beaverdell, launched at Lithgows, Port Glasgow on 27 August 1945 and followed by Beaverglen, Beaverlake and Beavercove plus three more former Empire-class wartime standard freighters: Beaverburn, Beaverford and Beaverlodge. "These ships, because of their heavy carrying of food, are known in the hard-pressed Mother Country as the 'B.U.' (bread unit) fleet." (Canadian Pacific 1947 Annual Report). Shipments of wheat, flour, beef, lumber and other commodities from Canada assumed vital importance while "dollar earning" British exports to Canada in the form of motorcars, motorcycles, bicycles, woolens, shoes and other manufactured high quality goods helped restore Britain's balance of payments. In 1948 CP ships carried over 500,000 tons of cargo in and out of Montreal.

Beaverbrae's voyage pattern reflected her dual purpose quality:

Eastbound (cargo service running with the other C.P. Beaver-class ships)

- Saint John, N.B. (winter) or Montreal (summer) to London Docks

- deadhead to Bremerhaven for passenger embarkation

Westbound (passenger service for sponsored immigrants and D.P.s)

- Bremerhaven to Halifax (winter) or Quebec (summer)

- deadhead to Montreal (summer) or Saint John (winter) for cargo loading

|

| The Route of the Beavers: Montreal (summer) or Saint John (winter) to the Port of London. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

With a 14.5-15-knot service speed, Beaverbrae took the best part of ten days to cross from Bremerhaven to Canada (but sometimes far longer in bad weather) and ran on a 28-day schedule with a five-day turnaround in Montreal/Saint John and a similar spell in London Docks for working cargo whereas her stay in Bremerhaven was only long enough to embark her passengers. Her outbound cargo, averaging 5,000 tons, was as important to post-war recovery as the settlement of displaced persons, consisting almost entirely of foodstuffs for a Britain desperately short of basic commodities and, if anything, its people enduring more restrictive rationing than during the war with the sudden end of Lend Lease supplies from the U.S. and Canada.

Her tentative schedule called for a five-week roundtrip with sailings from Saint John on 14 March and 20 April and her first arrival at Montreal on 20 May via Quebec.

The B.C. press also reported that her Chief Officer T. MacDuff was from Victoria, Purser R.G. Forrester from Vancouver and Chief Steward C.A. Sterling was also from Vancouver.

The trip was long, the quarters were spare and many of the passengers got seasick.

But the Beaverbrae will still be the focus, the common denominator in lives that changed course so dramatically decades ago.

'We shared all this hardship and then everybody was looking for a future for themselves and their children," Kilianski said.

"The ship was the tool.'

The Record, 30 September 2020

interview with Nelly Kilianski, who sailed in Beaverbrae in 1951.

So Beaverbrae began her career, a ship and service unique for Canadian Pacific and one that prospered for six years, or double the mandated span. Totally lacking in the pre-war glamour of the White Empresses nor in the anticipation of their post-war revival, Beaverbrae was afforded neither the lavish posters, brochure and publicity and went about her duties in relative obscurity. Her story was written mostly in the experiences of her passengers to whom their voyage was the last step in a long, often tormented and tedious wait to resume normal lives. There were storms, minor breakdowns, one headline grabbing extended strike, but hers was mainly the workaday routine of a passenger-cargo liner that still assumed a life changing role for some 38,000 people.

1948

On 29 January 1948 the Senate immigration inquiry in Ottawa was told that Beaverbrae would sail from Saint John, N.B. on 6 February and go into service. Instead she left on the 7th, in heavy snow, with a full cargo for London. arriving, at Gravesend on the 19th to unload her outbound cargo in London docks and then proceeded to Bremerhaven where she embarked 773 passengers.

Departing Gravesend on 27 February 1948 and proceeding to Bremerhaven, Beaverbrae sailed from there on the 29th for Halifax on her first passenger carrying voyage. Of her 779 passengers, 450 were predominently Polish displaced persons under I.R.O. sponsorship and the remaining 300 CCCRR sponsored ethnic German refugees. In all, her passenger list comprised Poles, Ukrainians, Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Czechs, Yugoslavians, Hungarians, Romanians and Germans, 261 men, 389 women and 129 children.

On 4 March Resources Minister Glen left Ottawa for Halifax to witness the first arrival of Beaverbrae. Another 860 "D.P.s" would arrived in Canada on the 7th aboard the I.R.O.'s chartered General Sturgis. Accompanied by A.L. Jolliffe, Minister of Immigration, and Capt. E.S. Brand, co-ordinator of shipping for immigration, Glen was also scheduled to inspect Aquitania which had begun a new immigrant service to the port from Southampton. In all, Canada planned to take in 100,000 immigrants in 1948, half from Britain and the Commonwealth, 10,000 Dutch farmers coming over in ships chartered by the Netherlands Government and displaced persons in Beaverbrae, General Sturgis, General Stewart or General Heitzelman.

|

| Credit: Montreal Gazette, 12 March 1948. |

Beaverbrae came into Halifax the evening of 9 March 1948; the first new Canadian Pacific liner since Empress of Britain in 1931. Her polyglot passengers were met and addressed by Minister Glen as the passed through the immigration procedures on arrival, saying "their opportunities of succeeding in this country would as great as ever and that diligence and thrift are the things that create homes in this free country in which you have just arrived." Glen and other officials inspected Beaverbrae from stem to stern and commented that "the arrangements of the company and the conditions of the ship are most satisfactory." Also meeting the ship were C.P.R. Immigration head A.L. Jolliffe, Capt. R.W. McMurray, Managing Director of C.P. Steamships and Capt. E.S. Brand.

|

| Among Beaverbrae's passengers on her maiden voyage were these three Polish orphans joining relatives in Winnipeg. Credit: Surrey Leader, 8 April 1948. |

One of the new arrivals, Mrs. Augusta Tews from Poland, told her daughter, Mrs. Arthur Braun of Kitchener, Ont., that "every day seemed like Christmas" aboard the ship and spoke of the "good food aboard, the free distribution of cigarettes and chocolate bars to passengers every day and the display of movies on board which depicted the new life the settlers might expect in various parts of Canada." (Montreal Star, 10 March 1948). Less sanguinely, some of the Poles expressed surprise at having "to share quarters with Germans whom they considered wartime collaborators of the nazis." (Calgary Herald, 10 March 1948).

The special train for Montreal left the quayside at 3:00 a.m. and that for the West at 4:30 a.m. In all, 49 of the arrivals would settle in Montreal, 19 in Ottawa, 250 in Toronto and elsewhere in Ontario and 429 in Western Canada.

Beaverbrae sailed from Halifax for Saint John where she arrived the evening of 10 March 1948 for loading cargo for her return to the U.K. and then onto London (9-10 April) and Bremerhaven to embark her next allotment of immigrants. In fact, Saint John would have four of C.P.'s "Busy Beavers" in port at week's end: Beaverdell, Beaverlake, Beaverburn and Beaverbrae which would carry a combined 20,000 tons of flour and 6,000 tons of meat in their holds for Britain out of a total of 41,000 tons of cargo.

|

| Credit: Montreal Gazette, 30 April 1948. |

With flags flying, 'The Maple Leaf Forever' blaring over a loudspeaker, and more than 770 new Canadians lining the rails for a glimpse of their new country, the Canadian Pacific’s 9,000-ton Diesel-electric liner Beaverbrae docked in Quebec yesterday.

The Daily Colonist, 30 April 1948

Marking her first arrival at Quebec as the St. Lawrence Season got underway, Beaverbrae which left Bremerhaven on 19 April 1948, docked there on the 29th. On the quayside to meet her were 33 former Canadian servicemen greeting their German fiancees aboard, among the 752 passengers (Polish, Ukrainian and German including 192 Mennonites) with 29 babies and 143 children among the total. "During the trip, the immigrants were shown movies of their new homeland. 'The movies come second in popularity to the meals though,' said Captain G.O. Baugh, master of the ship. 'Mostly displaced persons, the passengers hadn't eaten like that since before the war.'" (Daily Colonist, 30 April 1948). The same day 642 refugees landed at Halifax from Nea Hellas and another 398 due there on 2 May aboard Sobieski.

In all, 18,000 displaced persons had arrived in the Dominion since the beginning of the year. Typical of the dispersal of these new arrivals and the time it took them to travel across three-quarters of the country, 150 from Beaverbrae arrived in Edmonton the first week of May, comprising 40 families and some single persons with seven staying with relatives in the city, 12 heading for Barrihead and the remainder to various parts of northern Alberta.

Beaverbrae then continued upriver to Montreal where she made her maiden arrival on 30 April 1948 to load cargo for Britain at Pier 10. She sailed on 6 May and arrived in London on the 16th.

|

| Waiting to disembark at Quebec, 4 June 1948. Credit: The Gazette, 5 June 1948. |

On her third voyage, Beaverbrae left Bremerhaven on 26 May 1948 for Quebec with 773 passengers, including 114 Mennonites, establishing the remarkable "every berth filled" carrying of this ship, and she came into Quebec on 4 June. There, 516 boarded a 16-car train for Western Canada and another 250 one for the Eastern provinces. Of the passengers for the West, 450 were destined for Winnipeg and the far west. Beaverbrae docked at Montreal on the 5th and departed by the 11th for London (arriving 19th) and Bremerhaven. Rather a V.I.P. but now a "civilian" aboard was Capt. J.W. Thomas, CBE, of Vancouver, the retiring captain of Empress of Scotland through her war career and who left the ship in Liverpool. The commanding officer of Beaverbrae, Capt. R.A. Liecester, was also from Vancouver.

.jpg) |

| Credit: Vancouver Sun, 23 July 1948. |

Twenty more German fiancees of Canadian war veterans were among the 770 immigrants landing at Quebec from Beaverbrae at midnight of 17 July 1948. Too late for disembarkation, her passengers were on their way the following morning via two special trains. Normally cargo was not carried westbound but on this occasion, Beaverbrae brought in a special "souvenir" of the war, a full mock-up model of the famous prefabricated "Mulberry" harbour used in the D-Day landings and bound for the Royal Canadian Engineering School at Chilliwack, B.C. She even numbered among her passengers formal nobility of now occupied countries including Baron and Baroness Herbert Anrep. of Estonia and their two children, bound for Almonte, Ont. to join their cousin.

|

| Baron and Baroness Herbert of Estonia and their two children upon arrival at Quebec. Credit: Ottawa Citizen, 19 July 1948. |

Beaverbrae remained just as integral to Canadian Pacific's busy Beaver cargo operations. When she arrived at Montreal on 19 July 1948, she came in with Beaverdell and Beaverburn, making for 26 deep water ships in port that day. By the 24th, there were no fewer than six passenger liners (including the flagship Empress of Canada) and cargo ships of the line, totalling 68,000 tons, in the Port of Montreal, the busiest in over 20 years. At noon that day, the Empress sailed and Beaverbrae, loaded to the marks with over 5,100 tons of foodstuffs and general cargo, left for London (arriving on 2 August) and thence for Bremerhaven.

On her next voyage commencing on 9 August 1948, Beaverbrae broke her own passenger record with 784 landing at Quebec on the 18th. Of these, only 225 boarded the 10-car train for Montreal and connecting points as far as Toronto and the remainder fully taxed the capacity of the 16-car special for the West.

|

| A Lithuanian family is welcomed ashore from Beaverbrae by Canadian friends. Credit: Montreal Gazette, 19 August 1948. |

A sure sign of early autumn was the traditional mid September announcement of Canadian Pacific's winter sailing schedule which would begin after Empress of Canada was the last to clear Montreal on 27 November 1948. Beaverbrae would be first to inaugurate the winter programme from Saint John, N.B. upon her arrival there on 30 November from Bremerhaven and with her "Beaver" fleetmates would make the New Brunswick port her Canadian terminus but as the previous season, land her passengers at Halifax westbound.

Among those landing at Montreal on 22 September 1948 aboard Empress of Canada was the Rev. N.J. Warnke of Winnipeg who had been in Hanover, Germany for over a year directing immigration for the CCCRR, who told reporters that Beaverbrae "will henceforth be used entirely for the displaced persons movement" and that an estimated 3,000 new Canadians had been handled by the organisation in the past year.

The following day, Beaverbrae landed 770 new arrivals at Quebec on 23 September 1948, 570 entraining for the West on an 18-car train and 204 for Montreal and Toronto. She actually landed 772 including two stowaways, William Cruchley, 20, of Wellend, Ont, and Frank Fowler, 27, of Toronto, who managed to get aboard whilst the ship was in London. They were sentenced to 30 days in jail. Beaverbrae arrived at Montreal on the 27th and sailed on 2 October for London (11th) and Bremerhaven.

A total of 784 passengers disembarked at Quebec on 28 October 1948 (175 coming to Edmonton) and Beaverbrae carried on to Montreal where she docked the following day.

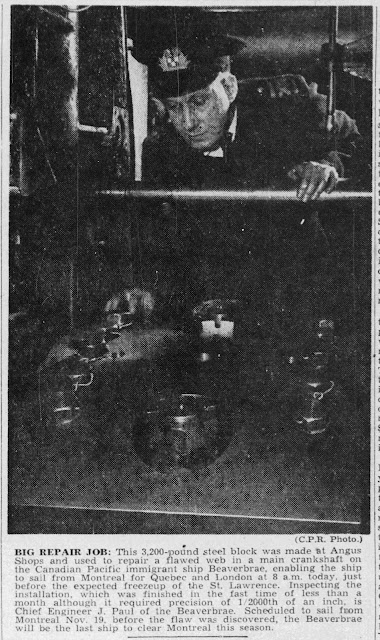

A six-day strike by the Canadian Seaman's Union (CSU) (to which Beaverbrae's crew belonged) threatened her sailing for London and Bremerhaven on 19 November 1948 but it was settled in time. Instead, a flawed web was discovered one of her diesel crankshafts, attributed by some to possible sabotage attempts before the Germans surrendered the vessel. With the manufacture of the part estimated to take nine months, thus marooning the vessel in port for the winter, it was instead decided to forge the 3,200 pound block in Canadian Pacific's own Angus Shops in Montreal.

Angus Shops workers were equal to the task. By working night and day, the shops forged a 5,200 pound of steel and machined it to strengthen the flawed shaft and shut off one piston of the diesel engine. Fourteen days later the block was delivered from Angus and the Beaverbrae sailed, the last ship to leave harbor that winter.

The Gazette, 7 July 1951

|

| Chief Engineer J. Paul checks out the repair to a main crankshaft crafted by CPR's famous Angus Shops, Montreal. Credit: Montreal Gazette, 10 December 1948. |

On 9 December 1948 repairs were completed and the motor successfully tested by which time she was the last ship in Montreal harbour. She was off at 8:00 a.m. the following morning for Quebec and London where she docked on 18th and welcomed for her full cargo of foodstuffs. Less welcome was John Anthony Calgie, aged 26, who was fined 20 for attempting to evade customs duty on 1,320 cigarettes, and 25 pairs of silk stockings and a quarter of a pound of tobacco after the goods were discovered in a cavity under a drawer in his cabin whilst the ship was lying at Royal Victoria Dock. He told the court that the goods were for his family in Glasgow whom he said he had not seen in five years and being Christmas, and thought the customs would not be so diligent in searching.

In 1948, Beaverbrae seven westbound crossings carrying 5,481 passengers and seven eastbound ones carrying 31 passengers.

|

| Beaverbrae leaves Royal Albert Docks in July 1949. |

1949

The winter season did not see any reduction in the arrival of immigrants and displaced persons in Canada. The first three weeks of the New Year saw seven liners arrive, landing thousands of new Canadians with Gripsholm (on her first arrival since the war) and Beaverbrae docking at Halifax, the later landing 783 DP's, on 15 January 1949.

|

| Scene at Windsor, Ont,, station on 17 January 1949 as over 300 relatives greet 58 displaced persons on arrival from Beaverbrae at Halifax on her first crossing of the year. Most would settle in Windsor and be reunited with family members they had not seen in 25 years. Credit; Windsor Star, 17 January 1949. |

In Ottawa on 4 February 1949 the Rt. Hon. J.A. MacKinnon, Resources Minister, told the Commons that 125,414 immigrants arrived in Canada in 1948, almost double the number in 1947. Of these, 46,057 came from the U.K and 16,957 from Europe including 10,169 Dutch and from Eastern Europe, 13,799 Poles and 10,011 Ukrainians.

On her next arrival at Halifax that season, Beaverbrae landed 782 passengers at Halifax after a miserably rough crossing of 11 days on 10 March 1949, no fewer than 180 bound for Alberta, 125 settling in the northern districts of the province.

|

| Beaverbrae strikebound in the Royal Albert Docks. Credit: Illustrated London News, 23 July 1949. |

That proved to be Beaverbrae's last arrival in Canada until...August during which time the vessel, officers and crew were involved, willing or not, in one of the great dramas of the year involving rival unions, communist machinations, the ports of Great Britain, longshoremen and eventually the Prime Minister and the King of England. In the end, it was a perfect (and needless) storm that summed up all the tensions of the Cold War then at its height. Lost in all was the ship's essential mission and the almost half year disruption in her sailings and the ability of her would be passengers to begin their new lives in Canada.

The full saga of the Canadian Seamen's Union (CSU) and The London Dock Strike of 1949 deserves its own chapter if not book and will not be attempted here, save the specific (and considerable) role Beaverbrae wound up playing in it.

It was to be an infamous year of labour unrest among Canadian seafarers amid an ongoing rivalry between the CSU and the Seafarers International Union, a division of the American AFL, to represent Canadian seamen. At the time, the CSU numbered some 34,000 members but was increasingly and widely known to be heavily communist influenced and in particular its leadership. Shipowners and the government preferred the AFL and when they began to sign contracts with it and not the CSU in early spring 1949, in late March 1949 CSU called a strike the Canadian National's Lady Rodney and Canadian Challenger and eventually spread to Canadian-flagged ships all over the world.

|

| Some of the principals among the CSU who brought about the strike both among its members in Canadian ships and in British ports. Credit: The Sphere, 21 July 1949. |

From the onset, the communist leadership of the CSU conspired to use Beaverbrae and her crew, then still the largest deep-sea Canadian vessel and on then vital "food run" from Canada to Britain, as an incitement to a wider and international strike involving equally radical elements of British dock workers in then largest port in the world, London. When it is today perhaps fashionable to sneer at the notion of the "communist conspiracy," the 1949 London Dock strike was nothing less. In November 1948, the CSU Secretary, Jack Pope, went to London and opened an office of the union in North Woolwich to begin organising and enlisting the support of the local dockers.

As for Beaverbrae, when she sailed on 26 March 1949 from Saint John, loaded with Canadian grain, flour and timber, she numbered among her crew 13 "handpicked Communist seamen," including Quartermaster "Bud" Doucett and Joe McNeill (who had never been at sea previously) who was described in the press and by an British M.P. as "a paid Communist agitator. They convinced the 85-strong crew to join the CSU strike upon arrival in the Royal Albert Dock on 3 April and four other Canadian ships in British ports also went on strike. Almost immediately radical elements of the dockers began picketing the "black" ships and refused to unload them.

By May, dock workers in Bristol and Avonmouth went out in support of the Canadian strikers and the disruption spread to Liverpool until 10,000 workers and 80 vessels were idled. The Transport and General Workers Union denounced the strikes which were not authorised by the union leadership.

|

| Some of the striking Canadians picketing in London. Credit: The Sphere, 21 July 1949. |

On 3 May another effort to get Beaverbrae unloaded failed when London dockers again refused to go aboard a "blacklisted" ship and a union official stated that it an effort were made to force stevedores to unload the ship, "it will mean another dock strike." The day Canadian Pacific signed a contract with the rival union, Seafarers International Union (AFL) and agreed to repatriate the striking crew to Canada with no victimization or prosecution upon return.

On the 11th the Court of Appeals in London ordered the 79 striking crew to leave the ship by noon the following day which they did, the 34 officers remaining aboard. The crew were put up by some of the sympathetic longshoremen. Beaverbrae had now been idle for 40 days and was joined in London Docks by Argomont and Ivor Rita, Seaboard Ranger and Roystone Range at Liverpool, Gulfside and Montreal City at Avonmouth and Seaboard Trader at Southampton. Harry Davis, head of the CSU addressed seamen and dockers in London on the 15th and on the 18th huge chalk written signs reading "Strike" appeared on Beaverbrae's pierside hull.

|

| Man in the Middle: Beaverbrae's Capt. Alexander Kennedy on the bridge of his ship during the strike wearing "civvies." Credit: The Sphere. |