Canadian Pacific perfects a glamorous combination of speed and luxury, names it Empress of Japan, and dedicates it to service on the Pacific Ocean, between the ports of Vancouver, Victoria, Honolulu, Yokohama, Kobe, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Manila.

This great steamship is the Canadian Pacific's latest conception of swift luxurious comfort in Ocean travel. Nothing on the Pacific matches it in speed. Nothing on the Pacific approaches it in size. Nothing on the Pacific surpasses it in sumptuous beauty. Empress of Japan in name, in fact is Empress of the Pacific, a steamship that glorifies transport on this most glorious of oceans.

Presenting Empress of Japan, Canadian Pacific brochure, 1930.

It would be hard to find any other series of ships, built for their own particular route, so splendid and outstanding in every way as the 'Empresses,' and particularly the utterly magnificent Empress of Japan, the finest of them all.

J.H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, October 1986.

A ship supreme, an Empress for the Ages, she was one of the first truly Great Liners of the 1930s. A vessel of prepossessing presence, she, unlike her contemporaries -- Empress of Britain, Normandie and Rex -- went on to a long and distinguished career of 36 years in peace and war. For the first nine, she dominated not the well trod North Atlantic sealanes, but the vast expanses of the North Pacific where she had no equal and remains to this day, the finest, fastest and largest passenger ship on that greatest of all oceans.

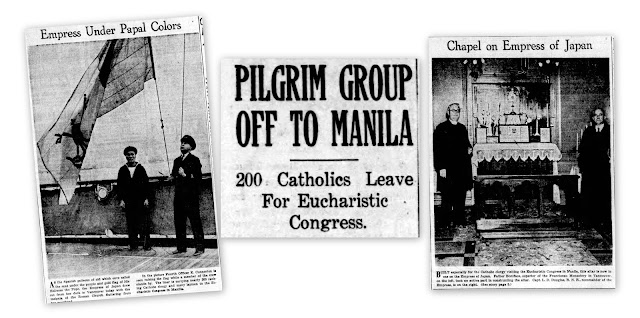

Her advent, with that of Empress of Britain, elevated an entire transportation system-- The All Red Route-- to a pinnacle of perfection, linking The British Empire and Mother Country by spanning a great Dominion twixt east and western seas, with liner and transcontinental railway, all under the Red Ensign. Yet, this was no stodgy imperial mailship, but a ship of matchless 'thirties flair, the most stylish of all British liners of her era whose glittering passenger lists including Babe Ruth, Pearl Buck, President Quezon and the King and Queen of Siam, summed up the last great Era of the Liner.

Her career on the Ocean Highways was long, but like most ships, she had her heyday, and this was doubtless and definitively her pre-war service as the undisputed Empress of the Pacific, 1930-1939, and this is the focus of this chronicle of but a phase of the life of this extraordinary passenger ship: R.M.S. Empress of Japan.

|

| R.M.S. Empress of Japan, Charles Edward Dixon (1872-1934), 1929. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| Forever Empress of the Pacific: R.M.S. Empress of Japan sails from Vancouver on her second voyage. Credit:Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

This article is dedicated to Dr. Wallace B. Chung of the University of British Columbia whose remarkable passion for the Canadian Pacific and breathtaking collection of photographs, brochures, documents and artifacts, now donated to the University, allows the story of the C.P.R. to be researched, recorded and shared with the world it uniquely spanned.

The launch of 16 ships, aggregating 213,000 tons, for one company within the space of three years provides a record unparalleled in the annals of the mercantile marine throughout world. All but three were built on the Clyde.

The Scotsman, 31 January 1930

The C.P.R. is a British institution, a link in the chain of Britain's All-Red communications around the world, but it is just as much an American enterprise as though operated under the States and Stripes. Probably as many Americans patronize the line and its steamships carry as much American cargo as do Canadian or British, and despite the intense appeal to Americans to travel on American ships, the Empress liners have held their own in the competition for American passenger and cargo trade. The clock-like schedule maintained by the C.P.R. on its trans-Pacific run has set an example of regularity in arrival and departure from the various ports of call, that other steamship lines have been compelled to follow.

By dint of hard, up-hill, persevering work, splendid performance, regularity, courtesy, safety and special attention to the wants of its passengers, the Empress liners have built up a reputation in the Pacific surpassing many of the more majestic floating palaces who cater to the luxury travel across the Atlantic. The C.P.R. is in the Pacific to stay. No matter how keen the rivalry, it can be counted on to keep at least one hop ahead of its competitors in the size, speed and appointments of its vessels.

The latest addition to the C.P.R. fleet is typical of that spirit of progress that within the next two decades, will be called upon to supplant the vessels of today with luxurious floating palaces for the Pacific as large as those now operating on the Atlantic.

The Far Eastern Review, August 1930

Epic Enterprise, two words that perhaps best sum up the origins and early history of The Canadian Pacific, from the construction of the trans-Continental Railway to the creation of the first coordinated global transportation system of railway, steamships and hotels to establishing a new trans-Imperial route. What had begun in 1881 reached a zenith half a century later with the commissioning of R.M.S. Empress of Britain for C.P.'s North Atlantic service, a year after the introduction of R.M.S. Empress of Japan for the Pacific service. Not only were they the ultimate realisation of C.P.'s President William Van Horne's "All Red Route," but they capped another era of Epic Enterprise begin in 1919 by C.P.'s current President, Sir Edward Wentworth Beatty.

|

| Sir Edward Beatty (1877-1943). Credit: City of Vancouver Archives. |

Sir Edward Wentworth Beatty GBE KC (1877-1943), the first Canadian-born President of Canadian Pacific was, without question, its most dynamic and expansionist since Van Horn, and one of the great Canadians of his age. Assuming the Presidency of C.P.R. reluctantly (his ambition was to be a judge) in 1918, Beatty transformed the Company in all its aspects, including late in his tenure, establishing Canadian Pacific Air Services. It was Beatty who built the Royal York Hotel in Toronto, the largest in the Dominion, and was forever a tireless champion of populating the great Canadian West. But it was mostly in C.P. ships did the "Beatty Touch" show, with the remarkable commissioning, between 1919-1931, of no fewer than 22 new ships at a cost of £20 mn., which gave C.P. the most up to date fleet in the British Merchant Navy and put Canada at the nexus of trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific travel.

|

| Largest of the initial C.P.R. post-war newbuildings was the Fairfield-built 21,517-grt Empress of Canada for the trans-Pacific run which entered service in May 1922.. Credit: Dalmadan.com |

The initial post-war C.P. Atlantic fleet reflected what Beatty believed was the future and role of the Company and for the Dominion as a whole: the populating of the great Canadian West, "the Empire's Breadbasket." If the United States severely restricted immigration in 1922, the British and Dominion Governments instead enacted comprehensive assisted immigration schemes which swelled the population of the country not to mention C.P.'s passenger lists. To cater to this trade, Beatty championed the so-called two-class "Cabin Boat" which the company had helped to pioneer with Missanabie and Metagama of 1915, and commissioned Montcalm, Montrose and Montclare in 1922.

For the Pacific route, the wonderful old Empress of Japan, the last of the original trio that had helped to establish C.P's first trans-ocean service in 1891, was replaced in 1922 by the 21,517 grt Empress of Canada. She and the Montcalms proved, with rampant post-war inflation, the most expensive ships per ton the Company ever contracted and Beatty turned to ex-German tonnage to further replenish the war-depleted fleet with Empress of Scotland (ex-Kaiserin Auguste Victoria) for the North Atlantic run and Empress of Australia (ex-Tirpitz), the later joining the Pacific fleet in 1922, bringing it up to the required four-ship level partnered with the 1913-built Empress of Russia and Empress of Asia.

The inspiration for the second generation of inter-war newbuildings could be summed up in two words: machinery and market. The immediate post-war ships, with their early geared Brown-Curtis turbines and conventional boilers had proven prone to breakdowns and were very heavy on fuel, whilst the adopted Empress of Australia had shown herself too slow for the trans-Pacific route. Moreover, during the prosperous 'twenties, C.P.'s North Atlantic trade shifted away from the carriage of assisted immigrants to a growing two-way tourist traffic whilst there was increasing demand for cargo space, especially wheat and lumber shipments.

To meet this new demand, it was decided to build a new fleet of fast cargo ships and a quartet of much more tourist oriented "Cabin Boats." There would also be a bold effort to tap the lucrative high-end trans-Atlantic trade from the U.S. Midwest away from New York, with a new "superliner" of a size, speed and luxury never before seen on the St. Lawrence route.

On the North Pacific, a ban on Chinese immigration had negated much of the traditional steerage trade and C.P. sought to instead cash in on the development of Hawaii as a tourist destination, begun in earnest in 1927 by Matson's new Malolo and the Royal Hawaiian Hotel. Whereas Honolulu was a regular call on the Canadian-Australian route from Vancouver to the Antipodes by Aorangi and Niagara, it was definitely "off track" for C.P's direct Vancouver-Far East run, to the tune of an extra 1,500 miles.

Such was the promise of the Hawaiian trade that the Company decided by the late 1920s to replace Empress of Australia (which would, after re-engining join the North Atlantic service) with a new, much faster 21-knot ship, intended like the new Super Empress for the North Atlantic, to be the largest and finest ship on her route and re-engine Empress of Canada to allow the pair to incorporate a call at Honolulu whilst still maintaining a 13-day passage time to Yokohama and sail from Vancouver to Honolulu in the same time (5 days) Malolo did the shorter run from San Francisco.

So it was that the epic newbuilding plan would itself be capped with the two most audacious passenger liners conceived for Canadian Pacific which in all respects proved to be the Ultimate Empresses on both the Atlantic and Pacific.

All of these new ships would incorporate the latest ideas and concepts formulated by C.P.'s Superintending Engineer, John Johnson, towards the adoption of very high pressure, superheated watertube boilers to materially increase their steaming efficiency and economy.

With typical Beatty drive and determination, all of this resulted in one of the most remarkable newbuilding and refit programmes of any British line. What was formulated in 1926 was entirely accomplished by mid 1931, giving Canadian Pacific the most modern fleet of any British or indeed any liner company. Further, it took advantage of lean order books in British yards in the mid to late 1920s and per ton, these ships cost far less than the initial post-war newbuildings whilst being of a far more modern quality.

Upon arrival at Southampton aboard Empress of Scotland on 3 June 1926, E.W. Beatty, when interviewed by the press, revealed his intention to place orders for seven new ships during his stay in Britain as well as the re-engining of Empress of Australia and her deployment on the North Atlantic. The total cost of the newbuilding contracts was estimated at £3 mn. or $15 mn.

Beginning the programme with orders placed on 25 June 1926 for the cargoliners Beaverburn, Beaverford, Beaverdale, Beaverhill and Beaverbrae and the first two 18,000-ton Duchesses (Duchess of Atholl and Duchess of Bedford) with Tyne and Clydebank yards, it was literally just the beginning. Two more Duchesses (Duchess of Richmond and Duchess of Cornwall which would be launched instead as Duchess of York) followed as did five Princess coastal vessels.

|

| A common sight along the Clyde in 1927-28, another new Canadian Pacific ship is launched. Here, Duchess of Richmond "takes the water" on 18 June 1928. Credit: dalmadan.com |

Epic Enterprise indeed and between 27 September and 23 November 1927 alone, more than 72,000 tons of ships for Canadian Pacific roared down the ways at Clydebank and Tyneside: the five "Beavers," Duchess of Atholl and Princess Elaine, a world's record for one private company. Added to these were three more Duchesses and Princess Norah launched in 1928, it made for 11 ships, totalling 138,898 grt, sent down the ways for Canadian Pacific in one year and two days.

In all, the Canadian Pacific newbuilding programme, 1926-1931, comprised the following

Name Tonnage Builder Completion

Beaverburn 9,874 grt Denny, Dumbarton Dec 1928

Beaverford 10,042 grt Barclay Curle, Glasgow Jan 1928

Beaverdale 9,957 grt Armstrong Whitworth, Newcastle Feb 1928

Beaverhill 10,041 grt Barclay Curle, Glasgow Feb 1928

Beaverbrae 10,041 grt Armstrong Whitworth, Newcastle Mar 1928

Princess Norah 2,731 grt Fairfield, Govan Dec 1928

Princess Elaine 2,027 grt John Brown, Clydebank Mar 1928

Duchess of Bedford 20,123 grt John Brown, Clydebank Jun 1928

Duchess of Atholl 20,119 grt Beardmore, Dalmuir Jul 1928

Duchess of Richmond 20,022 grt Beardmore, Dalmuir Jan 1929

Duchess of York 20,021 grt Beardmore, Dalmuir Mar 1929

Empress of Japan 26,032 grt Fairfield, Govan Jun 1930

Princess Elizabeth 5,251 grt Fairfield, Govan Mar 1930

Princess Joan 5,251 grt Fairfield, Govan Apr 1930

Princess Helene 4,055 grt Denny, Dumbarton Aug 1930

Empress of Britain 42,348 grt John Brown, Clydebank May 1931

In all, the 16 ships totalled 217,935 gross tonnage.

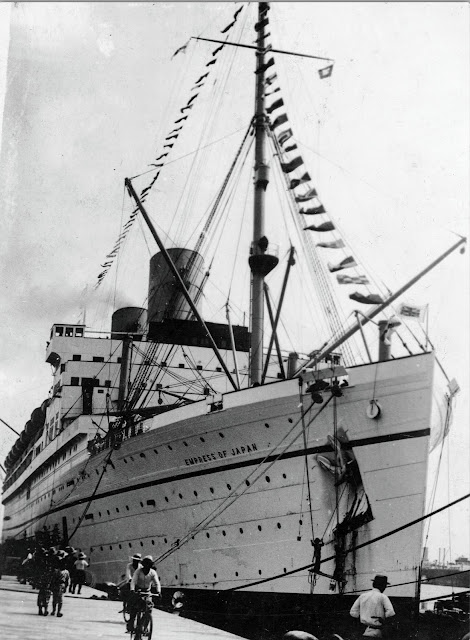

It was to be a return, too, to the era of The White Empresses of the Pacific and Canadian Pacific as announced on 20 December 1926 that starting with Empress of Asia during her forthcoming overhaul in Hong Kong, she and her fleetmates will return to the distinctive white hulls banded with blue worn before the war. Empress of Asia arrived at Vancouver so attired on 24 January 1927 following by Empress of Russia on 13 February and Empress of Canada on 6 March.

On 1 February 1928 the Glasgow Herald reported that "half a dozen British firms are understood to be interested in a proposed large passenger vessel for the Canadian Pacific Company's Transpacific service" and this was followed up on the 14th; "There are two large Canadian Pacific liners, it seems, instead of one, and are, it is understood, to be high-pressure turbine steamers. They are for the Pacific service. Five firms are interested in this service, and all of them have built vessels of this size and type."

Construction of a transpacific liner as large as R.M.S. Empress of Canada is planned by the Canadian Pacific Steamships Limited, for service out of Vancouver and Victoria, it is announced by Captain E. Beetham, general superintendent of the company.

Times Colonist, 17 February 1928

Captain Beetham, returning to Vancouver from a conference of C.P.R. executives in Montreal where plans for the new liner had been discussed, stated it was planned that the ship would be ready by 1930, to "be as large as the Empress of Canada," have a speed of 21 knots and would not replace Empress of Asia or Empress of Russia and bring the C.P. Pacific fleet to four vessels.

At the Annual Meeting of the C.P.R. at Montreal on 2 May 1928, Chairman E.W. Beatty revealed plans, "to replace one of the older first class vessels on the Atlantic service and build a new vessel of the same general type as the Empress of Canada for the Pacific service" and that the Company's directors had decided to ask the shareholders' approval for the construction of the two vessels. Beatty added that that "It is considered essential that a fortnightly service should be re-established on the Pacific, the future trade on which offers great possibilities."

In Britain to sign the contract, on 27 June 1928, E.W. Beatty announced the placing of an order with Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Co., Ltd, Govan, for the new Pacific Empress. Her preliminary dimensions were announced as 662 ft. (length), 83.5 ft. (beam), 25,000 grt,thus exceeding Empress of Australia as the largest ship in the C.P.R. fleet and 4,500 tons larger than Empress of Canada. This was followed on 30 July by the statement she would be "placed in commission on or before June, 1930" and be powered, like the Duchess-class ships, by high-pressure turbines of 25,000 shp and have a speed of 21 knots. It was further announced that to make her a suitable running mate, Empress of Canada would be re-engined in Britain, sailing from Hong Kong on 28 November via Suez and returning the following October.

|

| Early rendering of Empress of Japan showing her with the buff strake under her Promenade Deck as given to the other Pacific Empresses which she, in fact, did not receive upon completion. |

It is worth noting that the cost of the new ship, as reported in the company's Annual Report of 1928, £1.27 mn., was two-thirds of Empress of Canada whose astonishing cost of £1.7 mn. reflected the out of control inflation in shipbuilding costs immediately after the Great War.

As a fitting tribute to the storied first Empress of that name, it was announced in Vancouver on 4 September 1928 by E.W. Beatty that the new ship would be christened Empress of Japan which caused as much satisfaction in Japan as it did among nostalgic travellers and ship buffs. The old ship ranked as one of the most handsome ever built and on the 26th the Gazette (Montreal) suggested her namesake would be as good looking: "Her schooner rigging on the two pole masts and straight stem, raking slightly forward, combined with a white hull banded with blue and her smart yellow funnels, will give the effect of a beautiful yacht, through her tonnage of 26,000 gross, her eight decks and her service speed of 21 knots emphasize the difference between this white greyhound and the trim pleasure boats she will resemble."

|

| Another view on the keel for no. 634 on the slipway. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

On 18 December 1928 it was reported that the keel of the new ship (yard no. 634) "was being laid down" at Govan and that to date since the end of the war, C.P.R. had spent £12 mn. on new ships, not including the two new Empresses (the second of which, to be Empress of Britain for the North Atlantic run having been contracted in October). The exact date her keel was laid seems lost to time but photographs of the event show the almost complete hull of the light cruiser H.M.S. Norfolk still occupying the adjacent slipway and she was launched on the 12th. Yard no. 625, Taranaki for Shaw Savill, had been launched on 12 October and it is possible the keel of no. 634 was laid after the shipway was cleared. Framing of Empress of Japan was completed by March 1929 and fast progress on her construction continued apace.

|

| By late summer 1929, no. 634 had a name, Empress of Japan, and was well along in construction. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

In London on 31 October 1929, it was announced that Empress of Japan would be launched 17 December by Mrs. E.R. Peacock, wife of the Director of Canadian Pacific Railway.

Slipping down the greased ways enshrouded by fog that lifted as if by a miracle just as a mighty splash heralded the birth of a new sea giant the Canadian Pacific liner Empress of Japan was launched at half-past twelve today by Mrs. E.R. Peacock, wife of the Canadian financier. In charge of a veteran launching pilot and speeded on her way by hoarse cheers of thousands of the workers of the Fairfield Shipbuilding Company, the great liner destined to be the queen of the Pacific, slid rapidly and easily into her natural element.

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 19 December 1929

|

Dense fog overhung the city of Glasgow, the shipbuilding yards at Govan and the River Clyde on the morning of the launching date. Long before noon, the hour set for the launch, crowds of spectators from the surrounding districts were assembling at the Fairfield Company's yards. The tremendous bulk of the great white liner on the launching ways was, however, quite invisible from anywhere but the very nearest vantage points.

Even the invited guests of the Fairfield Company and the Canadian Pacific could not see her until they came with a few yards of the launching platform erected for the occasion under the ship's bows. Then, as they approached through the silvery fog, they became suddenly aware of the great and almost ghostly appearance of the white liner's towering prow looming majestically above them. Gradually a glowing red globe of sun to the eastwards gained slight power over the fog, revealing ever so little in places the graceful outlines of the ship, about which, like great skeletons in the gloom, stood the tall derricks and gantries.

But, although the launch was delayed moment by moment in expectation of a lift in the fog which shrouded the river, the word to launch was actually given with dramatic effect, while the grey mantle still hung thick upon the scene. Then the great ship, released by the touch of a lady's hand, paused for one last shuddering instant on the ways, murmured her good-bye to the thrilled group of guests on the launching platform, and in one second was gone into the veil of the mist.

Perhaps there has never been so swift and dramatic a departure of ship from launching place. Spectators gasped, then broke into a great cheer. After what seem almost an age of breathless doubt, the tremendous thunder of the checking chains, announcing their power to restrain the mighty bulk of the liner in her plunge into the Clyde, fell with reassuring clamor upon the ears of the waiting guests, again there broke forth a loud outburst of cheering. The good ship Empress of Japan was launched successfully, and the hoots of syrens from tugboats on the Clyde announced, through the gloom, that her little sisters of the river had welcomed her and were taking her safely in charge.

The Province, 19 January 1930.

|

| Ready for christening, Empress of Japan showing off her magnificent bows on the slipway. Credit: The Engineer. |

The launching of Canadian Pacific's largest to date liner, the largest ship to be launched that far up the Clyde River and the largest British-built liner since the Great War, was successfully accomplished albeit in dismal weather conditions, indeed so thick was the fog the morning of 17 December 1929 along the banks of the Clyde that the event was almost called off. On launching platform were Sir Alexander Kennedy, managing director of Fairfield; Sir George McLaren Brown, European general manager, C.P.R., Rear-Admiral Sir Douglas Brownrigg, Capt. J. Gillies, general manager of C.P.S. As it was when, at 12:30 p.m., Mrs. E.R. Peacock struck the hammer to release the bottle of champagne and activate the launching mechanism, the bottle merely bounced off the stem and a quick acting Sir Alexander Kennedy, took matters literally in hand and smashed the bottle against the hull just before it began moving down the ways. Such was the fog that the white painted mass disappeared in the gloom and only the dull roar and splash indicated to the onlookers that Empress of Japan was indeed afloat.

|

| In such thick fog as to obscure even the immediate onlookers, Mrs. E.B. Peacock about to launch Empress of Japan at Govan on 17 December 1929. Credit: Dundee Courier, 18 December 1929. |

|

| The Launching of Empress of Japan by Charles Pears. Commissioned by CPR, it was prominently displayed in the ship's main staircase and auctioned by Bonhams in April 2023. |

Uniquely, there were no published photographs of the launch indicating just how dire the conditions had been. However, the event was captured by famed British maritime painter Charles Pears (1873-1955) for a painting which had pride of place in the ship's main stairway.

At the post launch luncheon, Sir Alexander Kennedy, Chairman of the yard, "congratulated the Canadian Pacific upon the splendid share it has taken in the development of Canada and the Empire, and expressed his pride that his company, in building four Empresses of which the magnificent Empress launched today is the greatest."

It was made known on 13 January 1930 that Capt. Samuel Robinson, C.B.E., R.D., R.N.R., of Empress of Canada would be promoted to command the new ship. Capt. Robinson, who first joined the Company in 1895 at the onset of their trans-Pacific operations, was one of the most famous captains on the Pacific or indeed the Merchant Navy after his heroic actions during the Tokyo Earthquake in 1923 when commanding Empress of Australia which was in Yokohama at the time. Back when liners were real celebrities, his appointment only added to the building glamour and anticipation of the new ship.

|

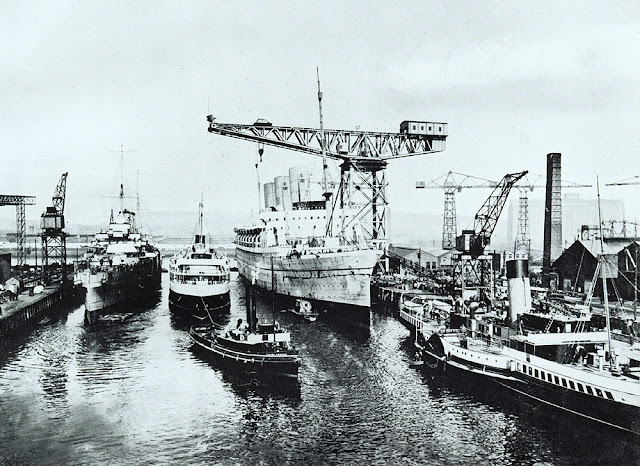

| Empress of Japan fitting out at Govan, February-March 1930. Credit: Dalmadan.com |

Early into the New Year and the new decade, British shipbuilding was enjoying prosperous and busy times, completing a flush of orders from the now past "Roaring 'Twenties" and before the slump in America spread worldwide. Fairfield's fitting-out basin in Govan was busy with Empress of Japan joined by the cruiser Norfolk with the C.P.R. coastal steamers Princess Joan and Princess Elizabeth on the stocks along with the new Bibby liner Worcestershire and two paddle steamers for Southern Railway, Southsea and Whippingham. Such activity extended down the whole of Clyde with Empress of Britain well underway at John Browns, two motorliners for New Zealand Shipping Co. and two turbine steamers (Karanja and Kenya) for B.I. at the Linthouse yards of Alex. Stephen.

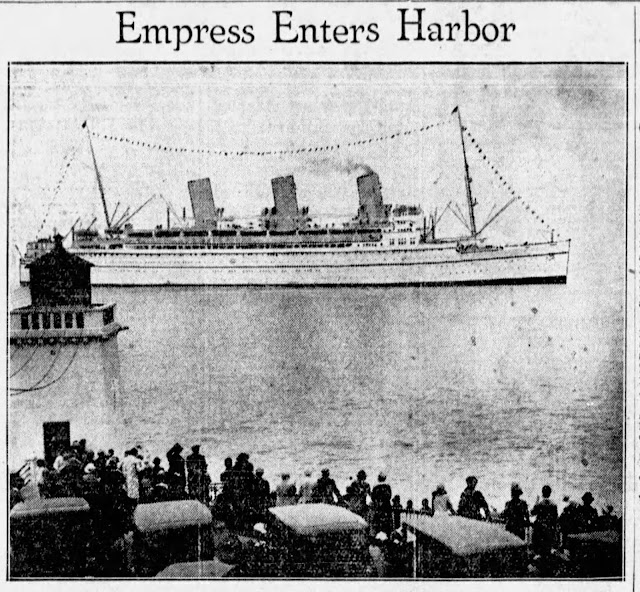

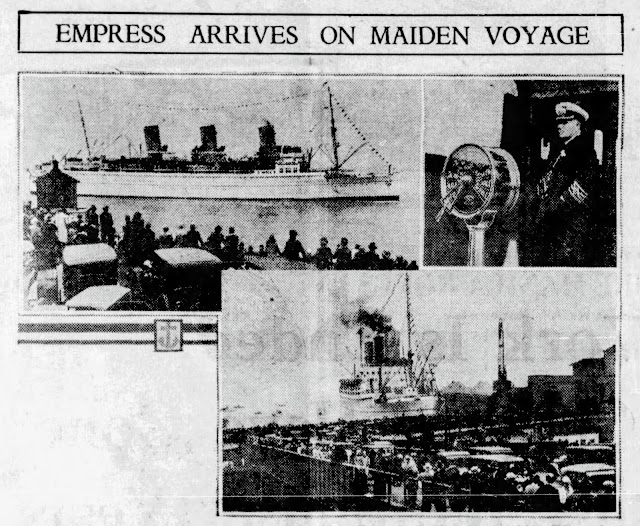

On 27 February 1930 details of the ship's first voyages were revealed. To provide a suitable long distance trials of her machinery (as had been done with Empress of Canada), it was arranged for her to make one roundtrip on the company's North Atlantic Express Service, departing Southampton on 14 June and arriving Quebec on the 20th. Sailing for Southampton on the 24th, she would leave there on 12 July for Hong Kong, in ballast, via Suez to take up her trans-Pacific duties on 7 August. Her maiden arrival at Vancouver was to be 24 August and her maiden westbound voyage on 4 September. In the event, she instead sailed from C.P.R.'s long established British terminus of Liverpool but would return to Southampton.

|

| Credit: The Victoria Daily Times, 6 June 1930. |

|

| Empress of Japan in the Clyde during trials. Credit: The Late Allan Green Collection Victoria Library Australia. |

Preparatory for her trials, Empress of Japan left Fairfields on 5 May 1930 for drydocking at Messrs. Workman, Clark's Thomson Dock, Belfast, and was undocked on the 8th. She was joined alongside by the new White Star liner Britannic at the deep-water wharf and scheduled, like the C.P.R. ship, to enter service in June, both representing the latest developments in large diesel and high-pressure steam turbine liners respectively.

Returning to the Clyde, Empress of Japan, commanded by Capt. Notley of Fairfield, began her trials on the measured mile at Skelmorlie on 11 May 1930. Exceeding the expectations of her builders, she achieved 22.38 knots on her full speed trials on the 12th before returning to Govan for final fitting out.

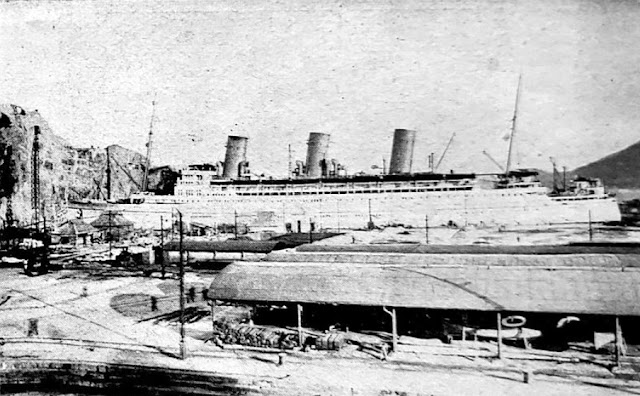

No effort was spared to ensure the new ship had a suitable and symbolic first arrival at her twin British Columbia homeports of Victoria and Vancouver. On 7 June 1930 plans were announced to celebrate her passing the mounted figurehead of the original Empress of Japan at Stanley Park, Vancouver, overlooking Burrard inlet, with a dipping of her ensign: "The prow of the former Empress, scarred by the sprays of 2,235,368 miles of travel between Vancouver and Manila Bay, silently will receive the homage of the new giantess who bears her proud name and witness the coming of the largest, swiftest and most luxuriously appointed liner on the Pacific." (The Victoria Daily Times, 7 June 1930). It was also mentioned that the new ship's Capt. Robinson, Staff Captain A.J. Holland, Chief Purser Ernst Syder and Chief Engineer James Lamb had all served in similar roles aboard the old Empress of Japan.

|

| Perfection accomplished, R.M.S. Empress of Japan leaves Fairfield's Govan yard as some of the men who built her watch her departure. Credit: Larry Sandu Collection via Flickr. |

Leaving the river of her birth, Empress of Japan departed Govan on 8 June 1930. As she sailed slowly down the Clyde, she passed the imposing hull of Empress of Britain on the stocks at John Brown's, Clydebank, three days before she would be launched by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales. It was a memorable first encounter indeed, representing not only the cap of one of the most significant newbuilding programmes ever undertaken by a single company in so short a span, but proving to be the apex of the Canadian Pacific shipping saga, the first meeting of what would be the largest, finest and fastest ships ever built for their respective routes.

On Whitsun Monday, 8 June 1930, Empress of Japan arrived at Liverpool and entered the Gladstone Dock.

|

| Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

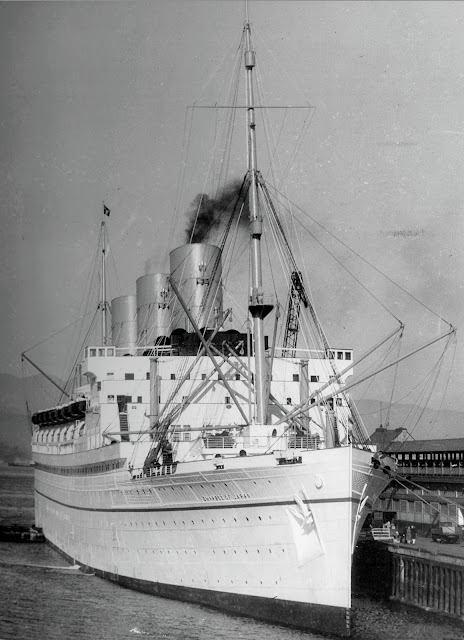

The Empress of Japan represents the last word, a new glorification to travel between Occident and Orient. Exteriorly the liner is a creation of flashing beauty. Hull and towering superstructure are gleaming white. A ribbon of blue beads the main deck and above all towers a trio of giant funnels painted the characteristic buff of the Canadian Pacific.

Cool, restful beauty, cool restful appointments characterize the interiors of the Empress of Japan, all designed to afford superlative comfort to passengers during warm Pacific days and nights.

The Honolulu Advertiser, 9 September 1930

... a truly magnificent ship, beautifully proportioned, graceful and yet with the look of tremendous power.

J.H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, October 1986

... She has the rake and sheer lines of 'thoroughbred racer.'

Pacific Marine Review, August 1930

Was there a finer passenger liner ever built? Speed, size, splendour, stylish interiors and sigh-inducing lines, Empress of Japan "had it all," a ship supreme in a decade that produced so many great liners. Literally the last word in trans-Pacific express liners, she, too, was the culmination of Canadian Pacific's ambitions to weld Canada into a vital link in the Imperial chain of communication. Paired with the magnificent Empress of Britain on the North Atlantic, these two Ultimate Empresses were without equal, ushering in a heyday that, like all good ones, was all too short. Those lucky enough to have been aboard Empress of Japan on any one of her but 58 round voyages, experienced the acme of ocean travel and the apogee of an era that was destined not to outlive her on the vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean.

|

| R.M.S. Empress of Japan, inbound from the Orient, approaching Vancouver. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

Like Empress of Britain, Empress of Japan was the epitome of the "one-off" ship, yet neither was created in vacuum or descended from the Ocean Liner Gods, but rather the combined culmination of that remarkable fleet of Canadian Pacific newbuildings of the mid 1920s. They owed much to the Duchesses of 1928 in their advanced naval architecture and marine engineering and to that magnificent if flawed German hand me down, Empress of Australia, for their lavish passenger facilities and accommodation. Empress of Japan, too, by her name and her duty, assumed the mantle of the matchless record of the first Empress of Japan and was a special ship all the more because of it. Fifty-eight times, her successor passed the figurehead of the old clipper-stemmed greyhound mounted in Stanley Park, as she cleared Vancouver, Cathay-bound, carrying on the tradition that forever put "Pacific" in Canadian Pacific and adding its greatest and enduring laurels.

The overall design of Empress of Japan was contracted to Messrs. C.S. Douglas & Co., Glasgow, headed by naval architect Dr. Charles S. Douglas (1874-1942) who had been involved in the design of nine previous newbuildings for Canadian Pacific. Earning his B.Sc. Degree at Glasgow University in 1899 and Doctor of Science in 1914, Dr. Douglas was for some years a member of the designing staff at John Brown & Co., Clydebank and later assistant to Sir John H. Biles, Professor of Naval Architecture at Glasgow University as well as being a business partner of Sir John for 14 years. He then started his own firm of consulting naval architects and engineers in Glasgow. Canadian Pacific's own Hugh R. McDonald planned many of the ship's passenger service areas and John Johnson, Chief Superintendent of C.P., was responsible for the design and specification of her machinery. Her interiors were designed by Messrs. P.A. Staynes and A.H. Jones. The same essential team would also be responsible for Empress of Britain. What a remarkable and wonderful pair of ships they created!

|

| R.M.S. Empress of Japan, outward bound from Vancouver. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

With principal dimensions of 660 ft. (length o.a.), 640 ft. (length b.p.) and 83.5 ft. (beam) tonnage measurements of 26,033 gross, 15,725 nett and 10,200 dwt, Empress of Japan was and remains the largest liner ever built especially for the trans-Pacific run. In size, she was exceeded only by her immediate (literally completed at the same time) contemporary Britannic (26,943 grt, 712 ft. by 82 ft.) as the largest British-built ship since the war at time of completion.

|

| R.M.S. Empress of Japan at Piers B-C, Vancouver. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| Empress of Japan alongside the Rithet piers, Victoria. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

There were nine decks in all: Sun, Boat, Promenade, "A" (Bridge), "B" (Shelter), "C" (Upper), "D" (Main), "E" (Lower) and "F" (Orlop). The hull was built on a two-compartment standard, divided by 10 watertight bulkheads with 21 sliding watertight doors, operating on the Brunton hydraulic system. There was a full double bottom carried out to the ship's side some 7-ft. and used for fresh water or ballast. For extra spaciousness, the Promenade Deck was extended 2 ft. over the sides and the deckheads heightened here as well as overhead domes or spaces which extended through to Boat Deck in way of the principal public rooms. Firedoors were fitted above "C" Deck at key locations.

|

| R.M.S. Empress of Japan: powerful, purposeful presence. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

Her extra deck, sweeping promenades, and huge funnels seemed somehow to increase her bulk disproportionately, and to both the passerby and the visitor on board the Empress of Japan seemed to be very much larger, in comparison to the Empress of Canada, than she actually was.

Empress to the Orient, W. Kaye Lamb.

Empress of Japan indeed dominated her running mate, Empress of Canada (21,517 grt, 627 ft. by 77 ft) but was as graceful as she was imposing. Few passenger liners before or since managed to combine a sense of power and proportion better than this latest and last Pacific Empress. Whilst Empress of Canada, like her contemporaries on the North Atlantic, the Montcalm-trio, continued the C.P. pattern begun with Misssanbie and Metagama of a hull centric appearance with low superstructure and thin funnels, Empress of Japan improved on the visual breakthrough achieved by the pacesetting Duchesses, melding perfectly a high freeboard hull with a solid, substantial superstructure that was quite built-up and dominate forward and transitioned to perfectly proportioned but quite massive and impressive funnels and what became a trademark, a cluster of very nautical cowled ventilators arrayed around each. Adding to the overall effect was the adoption of gravity davits which not only provided far more deck space but raised the lifeboats sufficiently to balance the high superstructure house behind them. The well flared bows with their massive and imposing anchor boxes, straight but raked stem and the traditional "sloped" cruiser stern transitioned well to a quite beamy hull and the whole packed topped off by lofty and well raked masts and, of course, that matchless White Empress livery. Overall, Empress of Japan simply looked... bloody marvelous.

|

| The Bows. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| The Bridge & Forward Superstructure. Credit: City of Vancouver Archives. |

|

| The superstructure and boats. Credit: City of Vancouver Archives. |

|

| The stern. Credit: City of Vancouver Archives. |

It is no exaggeration to say that the machinery of the Empress of Japan is one of the most efficient marine installations yet produced, says the August issue of The Shipbuilder. The design is the logical outcome of the ideas initiated by Mr. John Johnson, the owners' chief superintendent engineer, and which were embodied first in the Empress of Australia when that vessel was fitted with new machinery' at the Fairfield establishment a few years ago.

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 7 August 1930

If one man could be credited with revitalising Canadian Pacific's fleet, both cargo and passenger, trans-Atlantic, trans-Pacific and coastal, from the mid 1920s to the early 1930s, it was John Johnson, Chief Superintendent Engineer from 1924 up to the war. Whilst the company had invested heavily in a flurry of new ships immediately after the First World War, notably the three North Atlantic intermediates Montcalm, Montrose and Montclare and Empress of Canada for the North Pacific, their early Brown-Curtis geared turbines proved cantankerous and heavy on fuel. Adding to the mechanical woes was the otherwise splendid Empress of Australia, the former Tirpitz, which was ceded to C.P. as war reparations whose machinery was as unreliable as it was slow.

Enter John Johnson whose passion for high-pressure, superheated, high-efficiency steam turbine plants promising great economy and high speed formed the essential design credo of C.P.'s "second generation" of newbuildings in the mid 1920s, ships new and novel in every respect and among the most impressive on an engineering perspective of any British liners of the era.

|

| R.M.S. Duchess of Bedford, the first passenger vessel with high pressure superheated watertube boilers and one of the great groundbreaking liners of the inter-war period. Credit: shippinghistory.com |

Johnson first applied his theories with the re-engining and re-boilering of Empress of Australia in 1926 and even with conventional boilers working under moderate pressure but superheated, achieved a fuel consmption of 0.71 lb. of oil fuel per s.h.p. per hour whilst increasing her speed from 16.5 knots to 19 knots and a maximum of 20.34 knots on trials. The first use of Yarrow water tube boilers working at 252 psi combined with three-stage Parsons turbines was in the five-strong Beaverburn class of cargoliners of 1927-28. The real groundbreakers were Duchess of Bedford, Duchess of Atholl, Duchess of Richmond and Duchess of York of 1928, the first merchant ships with true high pressure (370 psi), a fuel economy of .625 lb., the first British Atlantic liners with gravity davits and the first British liners with contemporary interiors. They were the finest intermediate class liners in the world at their introduction and in every respect set the pace for the ultimate Empresses, Japan and Britain.

If Empress of Australia was the exemplar to exceed in accommodation, Empress of Canada was the ship to best in terms of speed and the new Duchesses' machinery the means to accomplish it. Designed with a service of 21 knots (comparable to the re-engined Empress of Canada), Empress of Japan could make 22 knots in favourable conditions and could, in effect, cut a day off the passage, doing the classic Vancouver-Yokohama North Pacific Express run, some 4,200 miles, in about eight days.

In fact, the greater speed of Empress of Japan and the decision to re-engine Empress of Canada to give her comparable service speed had less to do with record breaking and more to the decision in late 1928 to add Honolulu to the trans-Pacific run. The 1,500 extra miles for the diversion was only possible with far faster ships assigned to it. As it was, it was only originally effected westbound but in 1931 when both Empress of Japan and the re-engined Empress of Canada had settled down, it was made permanent in both directions for both ships whilst Empress of Asia and Empress of Russia maintained the direct North Pacific route. As it was, Japan and Canada were that much faster than their American and Japanese rivals, that they did Yokohama to Honolulu in just seven days, a day faster and could steam from Vancouver to Honolulu in the same time as Malolo, a much longer route.

Even so, Empress of Japan managed to break and hold practically every speed record along her route and segments thereof, some of which remained unchallenged until the 1960s. She remains the fastest liner ever built for the North Pacific service. Only when P&O-Orient began to operate Canberra and Oriana on trans-Pacific segments as part of round-the-world itineraries in the mid 1960s did these speeds be matched.

R.M.S. EMPRESS OF JAPAN

Principal Speed Records 1930-1939

Yokohama - Race Rocks (Victoria, B.C.) (direct)

22 August 1930 8 days 6 hours 27 mins. 21.04 knots

20 February 1931 8 days 3 hours 18 mins. 21.47 knots

17 April 1931 7 days 20 hours 16 mins. 22.27 knots*

*this was not beaten until 1962 by the American-flag cargoliner Washington Mail.

Yokohama - Honolulu (direct)

30 May 1935 6 days 8 hours 39 mins. 22.16 knots

April 1938 6 days 8 hours 33 mins. 22.17 knots

Honolulu - Yokohama (direct)

1 November 1934 6 days 16 hours 53 mins

Honolulu - Race Rocks (Victoria, B.C.)

20 March 1933 4 days 8 hours 3 mins 22.28 knots

Kobe - Yokohama

11 February 1931 15 hours 54 mins

Fastest Average Speed Obtained

May 1935 Honolulu to Race Rocks 22.37 knots

|

| One of Empress of Japan's main turbines (left) and one of the enormous Yarrow high pressure superheated boilers (right). Credit: The Far Eastern Review. |

Empress of Japan was the first (and, of course, only) Pacific Empress whose complete machinery installation was designed by John Johnson and represented, as did Empress of Britain, all of his innovations and achieved to maximum effect the economies, efficiencies and performance derived from them.

|

| One of Empress of Japan's massive screws, then the largest single cast propellers in the world. |

The machinery installation followed that so successfully introduced in the Duchesses although far more powerful. The engines were two sets of triple-expansion single-reduction geared Parsons turbines, each driving twin screws. At the time, Empress of Japan was the largest twin-screw liner in the world and her screws the largest single cast screws in the world at 20 ft. in. diameter and weighing 20.5 tons each.

The steam plant consisted of six Yarrow-type boilers, fitted with superheaters (725 deg. F), working pressure of 425 psi and operated under forced and induced draught. These were supplemented by two Scotch-type boilers, 17 ft. 8 in. in diameter, working at 200 psi, for auxiliaries. The boilers, all oil-fired, were arranged in two stokeholds, two Yarrow and the two Scotch boilers in the forward compartment and four Yarrows in the aft one, each venting into their respective working funnels. The third funnel, considered a necessity for the Chinese market, served to vent the engine hatch. Two 600 K/w turbo generators in the aft engine room and four diesel 308 K/w generators in the forward engine room provided the electrical supply. By using diesel generators, it was possible to completely shut down the steam plant in port.

|

| Arrangement of forward engine room showing the four diesel generators. Credit: The Far Eastern Review. |

The total weight of the machinery installation was 3,200 tons, a reduction of 200 tons over that in Empress of Canada, but generating one-third more horsepower. By reducing the number of boilers from 12 to six in the new ship, three tons of connecting piping alone was eliminated. Like Empress of Canada, the new ship carried 6,100 tons of oil bunkers and had a steaming radius of 13,000 miles.

The main engines developed 30,000 shp with five boilers on line (one usually being rotated on reserve for underway maintenance) giving the 21-knot service speed at 120 rpm whilst the maximum normal horsepower of 33,000 produced 23 knots. On her trans-Atlantic trials/working up voyage, she averaged 21 knots on 26,100 shp and her fuel consumption was but 168.8 tons a day for all purposes and only 154 tons for her main machinery. On her final record run, from Yokohama to Honolulu in May 1938, her 22.17-knot average speed was obtained at 28,908 s.h.p. 121 r.p.m. and she burned 195.32 tons day.

Overall, Empress of Japan's economy represented a 12 per cent improvement over the Duchesses, a remarkable achievement that well earned her a reputation for being one of the most efficient and economical express liners in the world.

|

| Sideview cutaway of the two boiler rooms (venting into the first two working funnels) with the swimming pool in between. Credit: The Far Eastern Review. |

In service, Empress of Japan proved both reliable and accomplished all that was expected of her as the doubtless Greyhound of the Pacific. With her high freeboard and long bows, she proved a fine, dry seaboat and only her massive superstructure and funnels caused some anxious moments coming into Victoria during windy conditions with Capt. Robinson declining to bring her alongside there if the winds there were too strong.

The second Pacific liner (following Aorangi) to have all gravity davits, which greatly increased deck space, Empress of Japan's boatage comprised ten 89-person capacity lifeboats, six nested 46-person boats, two 30-ft. motorboats with wireless and direction finding equipment and two 25-ft. emergency cutters with 46-person capacity, all at Welin-Maclachlan Patent Gravity Davits. Following C.P. custom, all of the boats were smartly painted mahogany colour.

Although primarily a passenger vessel, Empress of Japan had considerable cargo capacity, consisting of 304,000 cu. ft. including 59,000 cu. ft. on the Main and Lower Decks especially set aside for the silk trade and 33,000 cu. ft. of insulated space. If needed, the portable Asiatic Steerage space could be removed to bring the total cargo space to 380,000 cu. ft. whilst reducing Steerage berths to 480. The six holds were worked by a total of 23 derricks at the masts and three pairs of kingposts, the derrick at the foremast having a 20-ton load capacity, and all operated by electric winches.

R.M.S. EMPRESS OF JAPAN

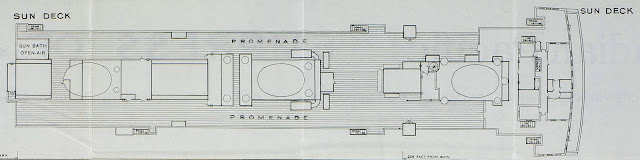

General Arrangement & Rigging Plans

(from Shipbuilding & Shipping Record, July 1930)

credit: William T. Tilley

(LEFT CLICK on image to view full size scan)

|

| Rigging Plan. |

|

| Sun Deck. |

|

| Boat Deck. |

|

| Promenade Deck. |

|

| Bridge (A) Deck. |

|

| Shelter (B) Deck. |

|

| Upper (C) Deck. |

|

| Main (D) Deck. |

|

| Lower (E) Deck. |

|

| Orlop (F) Deck. |

|

| Hold. |

Deck Plans (c. 1937)

credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia.

(LEFT CLICK on image to view full size scan)

|

| Sun Deck. |

|

| Boat Deck. |

|

| Promenade Deck. |

|

| "A" (Bridge) Deck. |

|

| "B" (Shelter) Deck. |

|

| "C" (Upper) Deck. |

|

| "D" (Main) Deck. |

|

| "E" (Lower) Deck. |

|

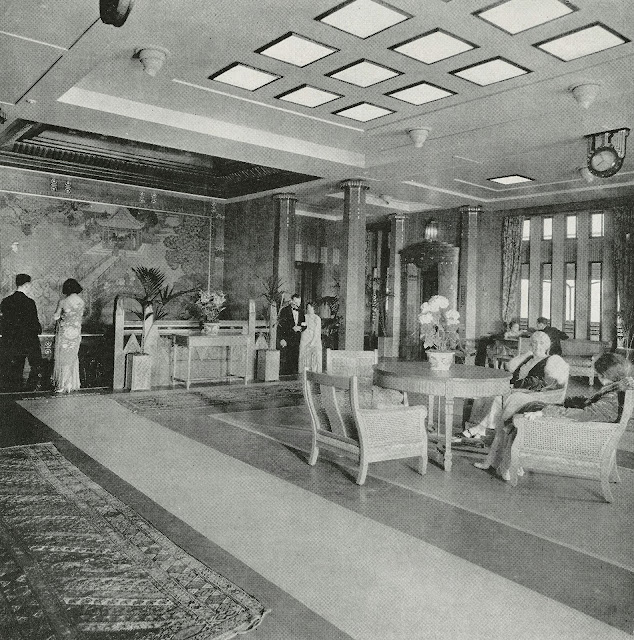

| Fit for an Empress: The Palm Court aboard Empress of Japan. |

The ornamental designs and costly furnishings of the public rooms, the majority of which are located on the promenade deck, immediately place the Empress of Japan in the front rank of luxury liner. The decorators, realising that a great number of her days will be spent in warm climates, have avoided the use of too warm furniture coverings.

The lofty walls of the public rooms are mostly of untouched or merely waxed wood, which enables the natural beauty of the grain to act as a main decorative feature. A fine example of this 'nature' treatment, which has been also carried out in the de luxe suites and special staterooms, is the lofty, glass-dome lounge in pale mountain ash and walnut. Characteristic here, as in all the public rooms on the Empress of Japan, is the wealth of light obtained by day from large windows and domes, and by night from a maze of electric light effects.

The Province, 19 January 1930

If the Duchesses formed the efficient basis for the new Empress' speed, their decor set the pace for her style. Indeed, like the Duchesses were on the North Atlantic, Empress of Japan was the first British non Atlantic liner with contemporary interiors. Together they created a unique C.P. look that managed to combine the metropolitan sophistication of London's Dochester Hotel with a hearty hint of Canadiana by virtue of their wealth of warm naturally finished woods (many of North American variety), strong almost rustic carvings and striking native American influenced striped and patterned soft furnishings. As such, they reminded one of Canadian Pacific famous chateau-like hotels in the Canadian Rockies and the West.

All of this came at the inspiration, as did everything connected with the Golden Age of C.P., of Sir E.W. Beatty who in addition to all he accomplished as the chief executive of the greatest transportation system in the world, was also a tireless supporter of education and the arts in Canada. He was determined that the second generation of inter-war C.P. ships assume a unique Canadian character that complimented that achieved with its hotels, including the Royal York in Toronto, the greatest hotel in the Dominion (and for a year, its tallest building), and one of Beatty's flagship projects which opened in 1929.

If the Royal York was designed by a Canadian firm, Beatty entrusted the interior design and decoration of the Duchesses and Empress of Japan (as well coordinating the interiors of Empress of Britain) to C.P's British corporate architects: Messrs. P.A. Staynes, R.O.I, and A.H. Jones, F.R.I.B.A, who typically as being "foreigners" managed to created something uniquely 1930s Canadian, a "Dominion Deco" if one might say, with their interiors that was delightfully distinctive yet establishing a "corporate image" that was one of the forerunners of the genre yet managed to do so with nary a beaver or maple leaf in any of it.

|

| A selection some of the poster art for Canadian Pacific by P.A. Staynes, that in the centre being for the new "Duchesses" he and A.H. Jones created the pacesetting interiors for. |

Percy Angelo Staynes (1875-1953) was a unique ship interior decorator being, first and foremost, an artist of considerable merit. Indeed, he was the only liner designer who, at the same time, created the visuals to promote those very same ships in the form of posters and brochure graphics. He worked as a painter in both oils and watercolours and illustrated several books including Roundabout Ways by Ffreda Wolfe (1912) and Gulliver’s Voyages the same year. Born in Nottingham, he studied at Manchester School of Art, the Royal College of Art and Julian’s in Paris. Staynes was elected a member of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters in 1916 and a member the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolour in 1935. During the First World War he served in the East Yorkshire Regiment and after the war, formed a partnership with architect A.H. Jones whose first major commission for C.P.R. was the design of their pavilion at the Wembley Empire Exposition of 1924.

With their first maritime commission, Staynes and Jones broke new ground with the Duchesses, not just in their decor but in their uniquely modern circulation areas that reminded of metropolitan hotels like the Royal York right down to the introduction of "revolving doors" from the promenade deck to the "lobby" with its arcaded shops, lifts and phone booths.

For the new Pacific Empress, something rather grander and more impressive was sought and here the inspiration for space and scale was Empress of Australia whose German-originated luxe and expansive character of her public rooms and accommodation had yet to be matched in the C.P. fleet, even by another ex-German liner, Empress of Scotland. For example, the deckheads of the Promenade Deck public rooms of the newest Empress were 14 ft. high, the same as Empress of Australia, and two feet higher than on Empress of Canada, whilst the dining room was anticipated by an expansive reception room/foyer and the dimensions of the First Class staterooms met or exceeded those of the Australia. In all respects, Beatty intended Empress of Japan to be the finest ship not only on the Pacific but of her size in the world.

|

| First Class sports deck (Sun Deck). Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class open promenade (Boat Deck). Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The total area of promenade space on Empress of Japan was 31,800 sq. ft., compared to 20,700 ft. on Empress of Canada and 16,500 sq. ft. on Empress of Australia. The sports deck, on the housetop of the Boat Deck, measured 240 ft. fore and aft and 17 ft. wide with the centre portion measuring 52 ft. by 32 ft. The open promenade on the Boat Deck extended some 310 ft. fore to aft and averaged 15 ft. wide whilst the open space aft, on a raised island, measured 50 ft. by 20 ft. The covered promenade on either side of the Promenade Deck was 310 ft. long, and 14-feet wide, four feet wider than the comparable space on Empress of Canada.

|

| First Class Gymnasium (Boat Deck). Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The Boat Deck, otherwise devoted to officers accommodation forward and 28 First Class staterooms (most with shared or private facilities) and all with windows, also had the First Class Gymnasium forward, an exceptionally large and well equipped facility with large windows and with a lift which accessed the indoor pool five decks below on "D" Deck. Some 300 ft. of open promenade flanked the deckhouse, three-quarters of which was reserved for First Class and the aft section for Second (Tourist) Class.

|

| First Class covered promenade looking forward (Promenade Deck). Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class covered promenade looking aft (Promenade Deck). Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The ship's showpiece was her Promenade Deck, one of the most impressive of any liner before or since. Taking full measure of the very long superstructure and her great beam, it was flanked by 300 ft. of expansive covered promenade, 14-ft. wide, and the interior featured 14 ft. high deckheads throughout with two-deck high domes and wells in the principal public rooms and circulating areas. Even without divided funnel uptakes, the use of glass doors and interconnecting foyers and long galleries permitted a clear 300-ft. portside vista aft from the Palm Court/Ball Room to the Smoking Room. The centerpiece and linking it all was vast Entrance Hall amidships, of large metropolitan hotel size and scale. Here, Canadian Pacific's aim of exceeding the spaciousness and grandeur of Empress of Australia was fully realised.

|

| First Class Palm Court (Ball Room). Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Palm Court (Ball Room). Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Palm Court (Ball Room). Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

Farthest forward, the Palm Court/Ball Room, was one of the ship's showpieces both for its spaciousness and successful dual purpose qualities. During the day, with its expansive sea vistas through large windows forward and on the sides, framed by palms and flowers in its Palm Court role and, during the evening, as a glittering Ball Room enhanced by its richly decorated ceiling which could be illuminated by color changing lighting effects. Ornamental fountains, flower boxes and lightly hued furnishings imparted the Palm Court flavour whilst the superb inlaid parquet floor and dramatically rendered orchestra platform gave the requisite Ball Room character and features. The panelling here was natural oak with gilded decoration.

|

| First Class Childrens Playroom. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The children's room on the starboardside of the Promenade Deck, directly aft of the Palm Court/Ball Room, was decorated to appear "as a red-tiled cottage standing in a painted flower garden. The illusion of a doll's house is complete, even to the wonderful toys and sleeping cots hidden in a bower at one end."

|

| First Class Card Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

Situated on the starboardside of Promenade Deck, aft of the Children's Room, the Card Room and the Writing Room were panelled in the early Georgian manner with a light coral hue in the Card Room whilst the Writing Room was painted in cream. Both featured soft, subdued lighting from a coved ceiling with mahogany furniture and a marble fireplace mantel as a centerpiece.

|

| First Class Long Gallery. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Long Gallery. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

That characteristic feature of British liners of the era… the Long Gallery… was partially introduced by Empress of Japan, linking the Palm Court/Ball Room forward with the Smoking Room along the port side and opening up along the starboard side to the immense Main Entrance to form a uniquely spacious open plan "T" shaped area. The Long Galley was furnished as sitting areas along the sides, with an expanse of windows facing out onto the covered promenade, and was simply panelled in ash and walnut.

|

| First Class Entrance Hall. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Entrance Hall. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Entrance Hall Shop. Credit: British Columbia Archives. |

|

| First Class Main Stairway. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

A centerpiece in every sense of the word was the Main Entrance Hall, one of the most impressive shipboard spaces of any liner of the era. The vast floor area was magnified by the two-deck high ceiling with its strikingly modern rectangular lights. An unusually large shop, with colonnades, was on the forward end, and aft was the superbly crafted Main Staircase, panelled in natural ash and walnut and featuring massive carved balustrades. Adding a metropolitan hotel flavour were the telephone boxes and the revolving doors (a feature introduced in the Duchesses) accessing the covered promenade whilst a pair of lifts were situated on the sides.

|

| First Class Lounge. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Lounge. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Lounge. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The Lounge was the most traditionally decorated of the First Class public rooms, rendered in "Empire Style." Sedate and elegant and flooded with natural light from a large oval domed ceiling and double height windows and luxuriously carpeted with rugs over a hardwood floor and with blue brocade-covered furnishings, it featured a large stage and orchestra platform and grand piano and on the other side, a marble fireplace. It was fitted with a cinema projector room at the fore end of the dome overhead so that films could be projected from these on to a screen at the back of the orchestra platform. Here, the panelling was pale mountain ash and walnut.

|

| First Class Smoking Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Smoking Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Smoking Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Smoking Room Bar. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The Smoking Room, striking the right balance between moderne and traditional, was suitably "woodsy" with a beautiful inlaid teak floor with walnut skirting and main panelling of light grained mahogany, studded with bronze nails to give a trellis effect. The focal point was a monumental fireplace in carved Roman stone with a cut-glass overmantel whilst the centre of the room featured an impressive hexagonal frosted glass skylight. There was a wonderful open American Bar on one side, set in a dramatic circular alcove.

|

| First Class Verandah Cafe. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Verandah Cafe. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Verandah Cafe. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The last of a remarkable succession of public rooms was the Verandah Cafe, open up aft of the Smoking Room and lined with stone effect panelling, jardinaires crowning the large windows and, of course, wicker furnishings.

|

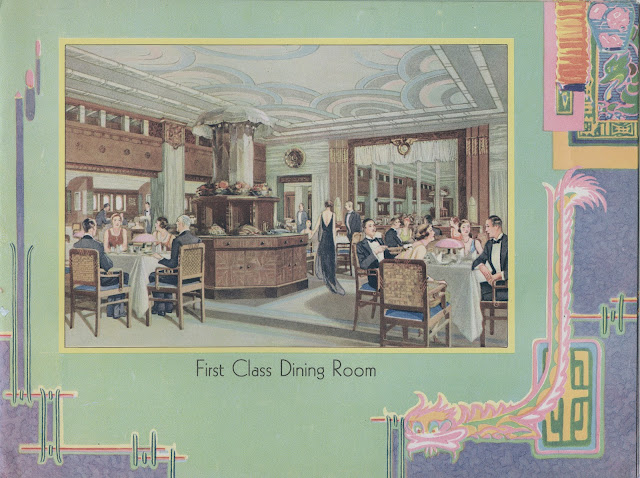

| First Class Dining Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Dining Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Private Dining Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class Private Dining Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

One of the showpieces of the ship was the First Class Dining Room on "C" Deck, seating 274 or, with the two adjoining private dining rooms, added, a total of 294 diners. Typical of the period, it was preceded by the spacious Foyer, decorated along the lines of Louis XIV with marble columns and bronze decorations, and leading off from the main staircase with its carved balustrades and illuminated alabaster ornamentation. Teak framed glass doors opened into the Dining Room which was impressively lined in a striking grey-green-blue veined Cipollino marble relieved by gilded bronze enrichments. The entire centre section was two decks high with a gallery along the port and starboard sides and a musicians balcony with an elaborate gilded bronze railing and decorations whilst on the opposite side was an large engraved mirror panel. The oversized portholes had sliding window screens and carved teak shutters. The chairs were impressively made of carved mahogany. Adding a moderne touch was the embellished ceiling set off by three parallel rows of strip lighting along each side.

|

| First Class swimming pool. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class swimming pool. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The swimming pool (30 ft. by 20 ft. and with a depth of 7½ ft.) on "D" Deck was directly linked to the gymnasium on Boat Deck, five decks above, and was rendered in green and black marble and "fitted out on generous line with a refreshment pavilion, a spectators' balcony, dressing boxes, an electric bath-- even with such luxuries as under-water light effects."

|

| Sitting Room of De Luxe Suites. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

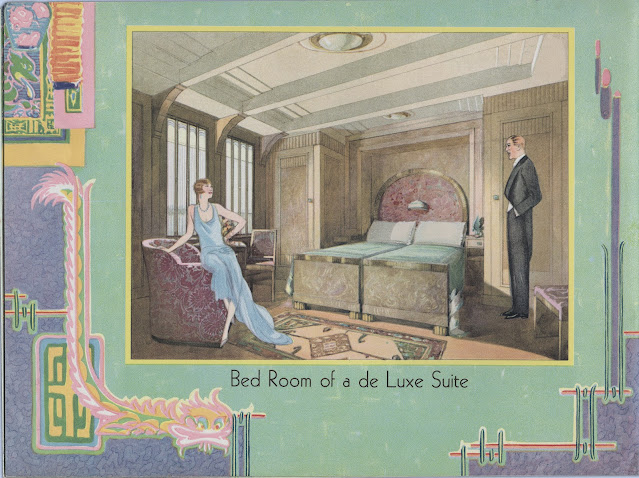

| Bed Room of De Luxe Suite. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| Bed Room of Peacock Suite. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| Verandah of de luxe suite. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| Sitting Room of Peacock Suite. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| Verandah of De Luxe Suite. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| Bedroom of Special Suite. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class stateroom. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class cabin bathroom. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| First Class two-bed cabin. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The passenger accommodation has been planned on the most modern lines, the first-class stateroom accommodation being based on that of the Empress of Australia a minimum, and the second and third-class based on the cabin and third-class stateroom accommodation of the new Duchess steamers.

Canadian Pacific brochure.

First Class had 268 berths in all lower bedstead cabins which could be increased by 30 portable upper berths in some cabins, there being no permanent upper berths. An additional 44 berths in Second (Tourist) Class on "B" Deck were interchangeable with First to bring the total up to 342 and with 38 other interchangeble cabins on "C", a maximum of 380. Of the 268 permanent First Class berths, they comprised two de luxe suites, 12 special twin-bedded cabins with private bath, 28 single-bedded cabins and 106 twin-bedded cabins of which two had private bath, 18 which shared a bathroom between two cabins, two with private shower and toilet and 24 sharing a toilet and shower between two cabins. The average area per passenger was 80 sq. ft. compared to 68 sq. ft. in Empress of Australia and 40 sq ft. in Empress of Canada or twice as much on the new Pacific flagship as her immediate predecessor.

In addition to the 26 cabins on Boat Deck, there were the two de luxe suites, 12 special staterooms and 61 cabins on "A" (Bridge) Deck and a further 43 cabins (and 22 interchangeable Second Class ones) on "B" (Shelter) Deck.

All First Class staterooms had a dressing table, triple folding mirrors, pedestal wash basin with hot and cold running water with one basin per one bedded cabin and two for twin bedded ones. All Bibby two-bedstead had five-foot passage to the ship's side with a settee and table at outboard end. All cabins were outside with porthole on the ship's side or Bibby except eight inside but had side from the deckhouse coming above. Almost all cabins had interconnecting doors. The de luxe suites were comparable with best verandah suites on Empress of Australia, each having a bedroom, sitting room, verandah, bathroom with bath, washbasin and bidet, and separate toilet, with a hall and a box room. There was single room adjoining each for use as a maid's room. The sitting room and bedroom could each be let as separate rooms with the verandah and bath and toilet, only with the bath and toilet. The special staterooms each had two large beds and a bathroom fitted with bath, toilet, washbasin and bidet. All cabins had steam heating and forced-draught ball louvre ventilation.

Six of the special staterooms were panelled in walnut with satinwood enrichments and six in Quebec birch and bean. In the suites, the bedrooms were finished in olive wood with furnishings in creamy purple damask whilst the sitting rooms were done in pearl grey and the verandas, with their large seaview windows, featured tiled flower boxes.

The Second Class (which was redesignated Tourist Class by 1931), with berths for 164, reflected the rather small market for this accommodation on the Pacific route, although it was more in demand on the Honolulu segment. Even so, it was of very high quality, comparable in many respects to cabin class on the Duchesses although the public spaces much smaller.

|

| Second (Tourist) Class Smoking Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The Smoking Room and adjoining bar, covered promenade and entrance/main staircase was right aft on Promenade Deck. The room was exceptionally well decorated and fitted out in classic "club" tradition with Austrian oak panelling, a fine fireplace and a Tudor style skylight over the centre. Substantial armchairs in a vertical brocaded fabric complete a most attractive room.

|

| Second (Tourist) Class Lounge. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

|

| Second (Tourist) Class Lounge. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The Lounge, directly below the Smoking Room, was aft on "A" (Bridge) Deck with the shop and covered promenade adjoining. This was panelled in cedar with gold inlays and featured a fireplace.

|

| Second (Tourist) Class Dining Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

Separated by the galley from that for First Class, the Second Class Dining Room, seating 128, was aft on "D" (Upper) Deck and panelled in Sycamore and oak with a very moderne flavour and tables for two, four and six.

|

| Second (Tourist) Class two-berth cabin. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

Second (Tourist) Class cabins (164 berths) were aft on "B" (Shelter) Deck (22 cabins) and "C" (Upper) Deck (24 cabins) mostly on the Bibby pattern with two and four-berths, the uppers being portable, and similar to those fitted in the Duchess class ships. By adding interchangeable Third Class cabins (86 berths) the total capacity could be raised to 250. Conversely, all Second Class cabins could be interchanged with First Class on a half capacity basis so that a two-berth would be let as a First Class single without the upper. All two-berth cabins had one large wardrobe between them and four-berth had two, full length mirror and washbasins with hot and cold running water, two being provided in four-berth rooms. Chest of drawers were also fitted. The ventilation and heating was the same as for First Class rooms. The average area per passenger worked out to 30.5 sq. ft. vs. 24 sq. ft. in Empress of Canada and 22.5 ft. in Empress of Australia.

Third Class, with 100 berths, was originally a separate class but later merged with Steerage as Third Class (enclosed) and Third Class (dormitory). It was situated right aft on "B" (Shelter) Deck with a lounge and smoking room on either side of the entrance with 2-, 4- and 6-berth cabins right aft on "D" (Main Deck).

|

| Third Class Lounge. |

|

| Third Class Smoking Room. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia (via Carol F. Lee) |

The Third Class Lounge was attractively decorated and furnished to a high standard with side banquet seating, card tables and armchairs and a piano was provided. The panelling was figured oak with screens to the sidelights. The Smoking Room, similar in size and on the other side of the entrance and staircase, was lined in sycamore and the entrance in light oak.

|

| Third Class Dining Room. |

Separated from that of Second Class by a block of Second Class cabins, the Third Class Dining Room was right aft on "C" (Upper) Deck and sat 52 at tables for two, four and six. Like the other public rooms, this very well fitted out with armchairs, decorative mirrors, large sidelights and panelled in sycamore and oak.

Third Class covered promenade space was aft on "B" (Shelter) Deck extending to the stern.

|

| Third Class four-berth cabin. |

The Third Class for 100 had 11 two-berth, 8 four-berth and eight six-berth cabins with one washbasin and wardrobe in the two-berths, two wardrobes and one basis in the four berth ones. The six-berth cabins had three wardrobes and two washbasins. The fittings etc. were along the lines of similar accommodation in the Duchesses. The average area per passenger was 19.5 sq. ft. vs. 16 sq. ft. on Empress of Australia.

|

| Asiatic Steerage dining space. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia (via Carol F. Lee) |

The Asiatic Steerage, for 548, was in open berth dormitories forward, partially in permanent accommodation and in partially in portable space with smaller individual compartments than previous ships. Right forward on "D" (Main) Deck were four dormitories with 52, 48, 28 and 50 berths respectively and again right forward on "E" (Lower) Deck were two 68- and 46-berth compartments.

|

| Asiatic Steerage open dormitory. Credit: Australian War Memorial. |

|

| Asiatic Steerage open dormintory. Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia (via Carol F. Lee) |

The dining space was on after end of "D" Deck, with separate galley and accessed through the working alleyway. Third Class "airing space" was situated forward on "B" (Shelter) Deck.

The officers and crew of Empress of Japan numbered 586 with 103 (deck), 7 (pursers), 123 (engineers) and 353 (catering). Most of the crew was Chinese with some 56 seamen and in the terminology of the era, 2 deck boys, 22 bell boys, 16 bathroom boys, 28 bedroom boys, 58 saloon boys, 32 steerage boys etc. The 10-strong orchestra was Filipino.

So it was with this splendid ship, that Canadian Pacific would write what would prove the last chapter of The Pacific Empresses and dispatch R.M.S. Empress of Japan on the first of 58 voyages, beginning her nine-year reign as the greatest of all passenger liners on Pacific.

|

| Credit: Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection, University of British Columbia. |

The Empress of Japan opens a new era in Pacific shipping, she brings Japan within 19 days of London, close to the time of the Trans-Siberian route, and very different in every respect concerning passenger comfort. With the three other ships on the service. The Empress of Canada, The Empress of Asia and The Empress of Russia, a fortnightly service in first-class liners will open from August 7th over the North Pacific in place of the three weekly service of the past.

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 4 July 1930.

Spanning two summers, it was truly a halcyon era for The Canadian Pacific. What had begun a half century earlier by binding together the Dominion from coast to coast by ribands of steel, then expanding its bounds to create a new ocean highway, an "All Red Route" of imperial commerce and with it, the greatest transportation system in the world, had now reached its pinnacle. With their introduction of R.M.S. Empress of Japan in July 1930 and R.M.S. Empress of Britain in May 1931, the Canadian Pacific nailed the red and white chequerboard houseflag to the proudest mastheads on the two great oceans, at once the largest, the finest and the fastest passenger ships ever to serve on their respective routes.

Of Empress of Japan's 36 years, she had but nine on the route for which she was designed and built, but what a time it was-- a heyday for a ship, a line and for ocean travel. Fifty-eight times, Empress of Japan steamed passed Brockton point and through Lion's Gate, pointing her bows south towards Hawaii and then westwards to the Orient. In summer 1930, a new White Empress, and the last of her dynasty, was about to start her reign as Queen of the Pacific.

|

| R.M.S. Empress of Japan sails from Liverpool on her maiden voyage to Quebec, 14 June 1930. Credit: Trove. |

1930

With President E.W. Beatty among those aboard, Empress of Japan sailed from Liverpool on 14 June 1930 for Canada, becoming the largest liner yet to depart the Mersey for Quebec. Prior to departure, he told the press that C.P.R. had no immediate plans for additional tonnage with Empress of Japan and Empress of Britain capping a truly remarkable newbuilding programme. As events proved, it be another quarter of century before C.P.R. commissioned another major liner, Empress of Britain (III). No finer passenger liners would ever serve the Dominion and no two ships better fulfilled the aspirations of the executive and the empire builder to make the Canadian Pacific truly the greatest transportation system in the world.