In 1920 the British India Steam Navigation Co. Ltd., took a most courageous step and decided to install in their new two 'M' class passenger vessels the first diesel engines in the company. It was surprising that this trial of the 'new' prime mover should have been made in the company's two largest ship while the diesel engine in that year was still in a fairly early stage of development.

J. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, June 1980

An important place in history will belong to the British India Steam Navigation Company's ship Domala, for she was the first oil motor-driven ship to be especially made and designed for carrying passengers. Her sister ship, the Dumana, has just been launched.

The Children's Newspaper, 30 December 1922

Once supreme among the merchant fleets of the world in number of ships and services, British India Steam Navigation Co. were so associated with The British Empire, that they have perhaps suffered in contemporary appreciation for that reason. The Imperial Progress that their ships-- liners, ocean going and coastal cargo ships-- enabled is no longer fashionable and the world's first global economy that they contributed to, dismissed if not disdained by those imagining what replaced it is even a notional improvement. Indisputable is the record of the greatest of all British shipping lines.

When added to the fleet, they were but two of no fewer than 158 ships totalling 915,857 gross tons and hitherto, individual British India vessels barely rated a mention on account of most being posted "out East," prosaicly plying their trade along the palm-fringed coasts, muddy deltas and teeming ports East of Suez, their Red Dusters hanging limp in the humidity-- a world away from a Mauretania or Majestic. Yet, Domala (1921) and Dumana (1923) were pioneering ships in the development of the diesel-driven merchant ship by British shipowners, naval architects and marine engineers and anticipated The Motor Ship Age later in the decade and into the 'thirties.

Domala was, in fact, the world's first purpose-built motor-driven passenger liner and the first powered by British-built diesel engines. She and her sister ran not on the North Atlantic Ferry but to the great port cities of the Raj-- Bombay, Karachi, Madras and Calcutta. They were manned by Indian Lascars and a legendary generation of British captains, deck and engineer officers. Their holds were filled with the give and take of Imperial trade and their passenger lists populated by the civil servants, tradesmen, engineers, mine and plantation owners, army and navy personnel and their families that enabled and defended it.

A century after they were introduced, occasion to discover and appreciate two pioneers and a vanished era of Imperial seaborne commerce they maintained:

M/v DOMALA (1921-1940) & M/v DUMANA (1923-1943)

|

| Official postcard for Domala and Dumana, by H.K. Rook. Credit: author's collection. |

The Domala is one of 20 similar vessels built or projected during the last nine years for the British India Company. Earlier vessels of her type have been fitted variously to run reciprocating engines with coal fuel, reciprocating engines with oil fuel, geared turbines with coal fuel and geared turbines with oil fuel. The adoption in the Domala of internal-combustion engines has established a basis for comparison of the relative efficiency, in sister ships, of five varying methods of propulsion, and the information obtainable should prove of considerable value in future marine engineering practice. The British India Company has five motor vessels now building, including one at Barclay, Curie & Co.'s yard, of the same tonnage and design as the Domala, and which will, like that vessel, be engined by the North British Diesel Engine Works.

Marine Engineer and Naval Architect, March 1922

Having been a part of every British war since the Indian Mutiny, transporting Tommy, Sepoy, Gurkha and Askari alike to the far corners of the Empire, it was perhaps ironic that BI, together with P&O, should lose 94 ships, totalling 543,530 tons, in The Great War, initially fought not for The British Empire but over Balkan backwaters squabbled over by two decadant and dying dynasties. Yet, the spoils of war put the literal meaning to "... wider and wider still..." and British India and P&O, united in corporation as they had been for decades in cooperation, picked up where they left off and, in many cases, never ceased. Throughout the war, the mailships continued to ply their lawful occasions and imperial trade never proved more valuable. Now it was to figure in a new dawn for British marine engineering.

The War had, as it did for so many British lines, interrupted ambitious fleet renewal and rebuilding programmes begun during the booming trade of the late Edwardian Era, whose ships reflected a high water mark for technical innovation and naval architecture. For British India, this including the "K"s (Karoa, Karapara, Karagola and Khandalla) for the Bombay-East Africa run, the "V's" (Varela, Varsova, Vita and Vasna) for the Persian Gulf service and, most importantly, the legendary "M" class (starting with Malda, Manora, Mashobra, Merkara, Mandala and Mantola), for what BI quaintly referred to as the "Home Lines" between India (one route from Bombay and Karachi and another from Madras and Calcutta) and East Africa and Britain.

|

| Malda of 1913: first of the "M" class, one of the largest and most successful groups of passenger-cargo liners ever built. Credit: clydeships.com |

The new British India steamer, Malda, which has been built at Whiteinch, has recently run successful trials on the Clyde. The Malda is intended for the London and Calcutta service of the company, and has large first and second-class passenger accommodation. She is 450 ft. in length, 58 ft. in beam, and of 8200 tons gross and 11,000 tons cargo capacity. On the measured mile she maintained easily a speed of 13 knots, the machinery running very smoothly. The Malda's passenger accommodation is exceptionally commodious and comfortable, and her passenger decks are very extensive. One of her features is the Inchcape cabins-patented about a year ago by Lord Inchcape, the chairman of the British India Line. Each of these inside cabins has a large, broad passage from the centre of the cabin to the side of the ship and leading to a large port, giving as much light and air as if the cabin itself were at the ship's side. Lord Inchcape was on board during the trials, and expressed himself as thoroughly satisfied with the vessel. The Malda is the first of a number of her class which are now under construction for the British India service from London to Calcutta, to Kurrachee and Bombay, and to East Africa and Durban.

Marine Engineer & Naval Architect, June 1913.

Measuring 450 ft. x 58 ft., and just shy of 8,000 grt, and powered by twin-screw triple-expansion engines giving at speed of 13 knots, the "M"s were handsome, workmanlike ships with good earning capacity of 10,000 tons of cargo space and two class accommdation for 75 passengers. After the initial pair, Mashobra and succeeding examples had one extra superstructure deck and accommodation for 130 passengers. They were ideal for BI's Home services which, under the amalgamation with P&O, remained as a secondary service to P&O's legendary Bombay Mail and their saloon accommodation extremely popular being priced about £10 less than for the faster, bigger mailships. Under Inchcape, "his" BI ships, too, never wanted for superb service, cuisine and standards and many preferred the homely little "M"s for their travel. In all, 19 "M"s were built, making it the largest class of passenger-cargo ships ever built.

|

| The Swan Hunter-built Mongara of 1914: she and Mashobra (Barclay Curle) introduced the extra superstructure deck and set the pace for all succeeding "M"s. Credit: tynebuiltships.co.uk |

Indicative of the rigours of the War on the BI fleet as a whole, of the initial six "M"s, two were sunk by enemy action (including the lead ship Malda) and two under constuction during the war completed as Admiralty tankers.

Rebuilding the post-war BI fleet would have as its linchpin, an improved "M" class, all except two built by Barclay Curle and eventually comprising no fewer then ten ships (and an additional two built during the war and rebuilt as cargo ships) of which six ("M3s") were 15 ft. longer and had cruiser sterns. The design proved adaptable enough to permit BI to incorporate triple-expansion steam machinery, geared turbines and most novel of all, diesels. It was a remarkable class of ships, representing the largest group of passenger ships built between the wars or indeed, after, and which would see BI through to the middle of the 1950s.

|

| Beautiful cover art for brochure for Mantola, one of the six-strong improved "M3"s with geared turbines and 465 ft. length. Credit: eBay auction photo. |

Ordered in early 1919, British India were fortunate indeed to have all of them completed, save one, by mid 1922 given the far more protracted construction of the enormous combined Cunard-Anchor-Donaldson line intermediates. Such was the output of "M"s that some had to wait their turn for trials and as a class, their sheer number mitigated their coverage by both the regular press and even shipping journals, all except two which concern us here.

British India post-war "M" class ships (all built by Barclay, Curle-- except Modasa (Swan Hunter) and Mulbera, Alex. Stephen) and listed in rough order by builder no.)

Masula (1919-1952), no. 516, 7,261 grt, 450 ft. x 58 ft., trp-exp steam,Mashobra (1920-1940), no. 577, 7,288 grt, 450 ft. x 58 ft. trp-exp steamMundra (1920-1942), no. 578, 7,275 grt, 450 ft. x 58 ft., trp-exp steamMagvana/Domala (1921-1940), no. 579, 450 ft. x 58 ft., dieselsManela (1921-1946), no. 580, 8,303 grt, 450 ft. x 58 ft., geared turbinesMadura (1921-1953), no. 585, 8,975 grt, 465 ft. x 58 ft., geared turbinesModasa (1921-1954), no. 1101, 8,986 grt, 465 ft. x 58 ft., geared turbinesMantola (1921-1953), no. 586, 8,963 grt, 465 ft. x 58 ft., geared turbinesMatiana (1922-1952), no. 587, 8,865 grt, 456 ft. x 58 ft., geared turbinesMalda (1922-1942), no. 588, 8,965 grt, 456 ft. x 58 ft., geared turbinesMelma/Dumana (1923-1943), no. 593, 8,428 ft, 450 ft., dieselsMulbera (1922-1954), no. 486, 9,100 grt, 466 ft. x 60 ft., geared turbines

There was some method to BI's choice of machinery even if the above list indicates it was in complete disregard to builders no. or date of completion. The final two counter-sterned 450 ft.-long "M2"s would introduce new machinery with no. 579 (Magvana) fitted with with twin-screw diesels whilst no. 580 (Manela) introduced geared turbines and following no fewer than six of the "M3"s (465 ft., with geared turbines and cruiser sterns), no. 593 (Melma/Dumana) reverted to the "M2" Mashobra hull form and would be the final ship of the long series. It is likely done to await results on the diesel machinery fitted to Magvana and Melma/Dumana indeed had a different arrangement of her machinery than her sister and would be the last of the "M"s to be laid down, in March 1923. It will also be noted that plans for no. 579 (Magvana/Domala) were inked on 10 May 1919 by Barclay Curle (drawings no. 1274) showing engine spaces for diesels. A second midsection plan was inked on 2 November.

An order has been placed for a large Diesel-engined motorship with Barclay Curle & Co. of Glasgow by the British India Steam Navigation Co. The machinery will be built by the Diesel Engine Department of Harland & Wolff.

Motorship, June 1919

The North British Diesel Engine Company, for instance, who had works erected at Glasgow, intended to construct only the Krupp two-cycle motor, but have now decided to build a four-cycle machine to their own design, and hope within the next few months to be manufacturing Diesels of 3,000 hp to 4,000 hp. Already the firm are reported to have received. orders for a number of high-powered of this type for installation in British ships.

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 19 June 1919

Few if any British India vessels were introduced with as much interest and publicity as that which attended the news that two of the now ubiquitous "M"s would be built with diesel machinery. Indeed the construction of the previous eight such vessels since the end of the War was accomplished in relative obscurity and the only plans for the class published in the various shipbuilding and marine engineering journals were for the two diesel variants. The motor ship lobby was intense in Britain where the techology was given so much promise and stealing a march on foreign competition in the field, notably German, was seen as at least one tangible fruit of a hard won victory. Thus, having the largest British shipping firm decide to fit diesels in two of their largest and latest passenger ships was a major coup.

One of the reasons for the installation of Diesel - engines in this large fleet of ships is the keenness and interest which Lord Inchcape has displayed in the development of the motorship .

Motorship, May 1921

Domala and Dumana were epoch beginners rather than makers, but they were indeed first. The first motor driven passenger ships laid down as such, they were also the first powered by British designed and built motors and auxiliaries. They were remarkable, too, in their boldness and doubly so for a line not hitherto associated with technical innovation or risk taking. If nothing else, they were among the singular achievements of one of the world's most exceptional shipping men, James Lyle Mackay, 1st Earl of Inchcape (1852-1932), who by his example made British India S.N. the largest merchant fleet in the world and, on the eve of the First World, achieved the union of true giants when he engineered the merger of the P&O and BI.

Rebuilding from the war, which cost BI alone two score ships, BI numbered 161 vessels in their fleet in 1920. It could this be argued that they could afford to "experiment" with new technology on a handful of them, although the endeavour was not confined to Domala and Dumana alone:

"D" for Diesel: Pioneering BI Motor Ships 1921-23

Domala (1921/8,441 grt) passenger-cargo liner, Barclay Curle/North British DieselDumana (1923/8,428 grt) passenger-cargo liner, Barclay Curle/North British DieselDumra (1922/2,304 grt) coastal passenger-cargo liner, Charles Hill/North British DieselDwarka (1922/2,328 grt) coastal passenger-cargo liner, Charles Hill/North British DieselDurenda (1922/7,241 grt) cargo liner, R. Duncan/North British DieselDalgoma (1923/5,953 grt) cargo liner, Alex. Stephen/Sulzer

|

| Credit: Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 7 May 1925. |

British engineers and engine makers, not shipowners, created the British Motor Ship. Vickers of Barrow introduced the diesel to the Royal Navy, but it was Swan Hunter who led the way with merchantmen, building Swedish designed AB diesels under licence at the beginning of the 1920s, and more importantly, helping to establish the North British Diesel Engine Works, at Whiteinch on the Clyde adjacent to the Barclay Curle yards. That Barclay Curle were part of the Swan Hunter Group and that together they built much of the BI fleet after the war (on a cost plus 22.5% basis) made it hardly surprising that of the 11 ships powered by the first North British Diesel Engine Co. motors, only one was not for BI. Of the ships fitted with the four-stroke, twin-screw installation-- Domala, Hauraki, Durenda, Dumra, Dwarka and Dumana-- all except Hauraki (NZ Shipping Co.) were BI ships.

Thus, the decision by BI, given their size and standing in the world's merchant shipping, to install the latest North British Diesel four-stroke engines on two of its new and largest ships, was of itself a huge coup for the company and the British motor ship industry. Because of the cost-plus contract, however, BI paid an extraordinary £37.7 per brake horsepower for the main engines and auxiliaries and by comparison, a later Doxford installation with electric auxiliaries (as the BI ships had) cost £27.2 per bhp by 1928.

|

| The main engines of Domala and another set behind, being built at the North British Diesel Engine Works, Whiteinch. Credit: Marine Engineer and Naval Architect, February 1922. |

Details of the ship's machinery were published in Motorship's November 1919 issue and "now under construction at the plant of the North British Diesel Engine Company at Whiteinch, Glasgow, from their own designs. Each engine of the three ships that the British India S.N. Company will operate has eight cylinders, 26½ in. bore by 47 in. stroke, and will develop 2,330 ihp (equivalent to 2,250 steam ihp) at 96 rpm and is of the four-cycle, single-acting, direct-reversible type. So while a good piston speed is allowed, namely 752 per minute, the engine turns at low speed, giving good propeller efficiency." It was also mentioned that they would be most "completely electrically equipped than any motorships at present in service, all the deck and engine-room auxiliary being Diesel-electric driven; even the ranges in the kitchens and galleys will be electrically heated." To generate all this electricity would be two six-cylinder North British diesels of 400 hp driving air compressors, and two 300 hp engines driving electric generators.

Magvana is now near launching stage. Will carry 135 passengers and 9,250 tons of weight/cargo. Will burn 16 tons of oil per day at 13 knots. One of the two sister ships on orders has been named Melma.

Motorship, August 1920

Magvana was launched on 24 December 1920, and in keeping with the all the interest centered not on the ship but her machinery, this was largely ignored by the press with no mention of any christening ceremony or photos of the event. It was, afterall, just another "M" class ship going down the ways and in that year, one of but nine such vessels launched that year, the classic undistinguished individual of a remarkable collective.

|

| Megvana (above) and Melma curiously retained the counter stern of the earlier "M2" class. Credit: Motorship, November 1921. |

|

| One of the two main engines being shipped aboard Megvana in January 1921. Credit: Marine Engineer and Naval Architect, February 1922. |

The installation of her engines in January 1921 aroused enormous interest, also being the first ship to have machinery installed by the new 150-ton hammer-head crane (built by Sir William Arrol & Co.) and 900 ft. quay wall at North British Co.'s Whiteinch yard.

This was but one of six pioneering diesel-driven ships commissioned by BI during this period and given their distinction and the attention aroused both in the popular press and technical journals, it was decided that they be given disinctive names, all beginning with "D"... denoting Diesel of course. All of the others.... Durenda, Dumra, Dwarka, Dalgoma and Dumana (laid down as Melma)... were launched so-named and by May 1921, Megvana's name had been changed to Domala but with no formal announcement to the effect.

It is of interest to note that several of the engineers who are to sail on the Megvana and sister ships, are at present in the shops and making themselves conversant with the engines, as they are being built and tested. This is a sound and wise policy for both owner and builder, and will have as its outcome the speedy training of a capable and confident staff of engineers.

Motorship, April 1921

Full trials of port main diesels at North British Diesel Engine Company, Whiteinch, were conducted from 4-11 April 1921 during which "every satisfaction was given. At the end of the test the engine was manoeuvred several times at full - load and finally reduced in speed to 28 revolutions per minute , at which speed the cylinders all fired regularly. " (Motorship).

Domala ran preliminary trials on Clyde over 21-24 November 1921, recording 13.5 knots on four runs of the measured mile off Arran. Lest anyone doubt this was both a heyday for British India Line and Clydebank shipbuilding, consider that the Glasgow Herald of the 25th wrote: "This vessel is now at the Tail of the Bank awaiting official trials, which have been delayed till next week because of the Madura, another British India vessel, running at the end of the week. Speed trials for a third British India vessel, the Mantola, will take place in about two weeks' time."

The Domala is the first vessel built as a passenger ship and fitted with internal combustion engines, and judging from the results of the trials it is not too much to say that this mode of propulsion will be the power of the future.

Glasgow Herald, 8 December 1921

|

| Domala on trials on the Skelmorlie measured mile, December 1921. Credit: Shipbuilding & Shipping Record, 29 December 1921. |

Two days of acceptance trials followed on 5-6 December 1921. Full speed runs recorded a maximum speed of 13.75 knots at 5,200 ihp and on her ensuing 48-hour endurance tests, Domala maintained 13.25 knots, with "highly satisfactory results, both as regards economy and reliability, the engines running throughout the test with absolute smoothness and regularity. The quietness of the engines and the coolness of the engine room are very conspicuous qualities, and the smooth running of the engines is a notable feature. The economy of the fuel is calculated to make the vessel a great commercial, the consumption of oil being very low," (Shipbuilding and Shipping Record, 15 December 1921), it being recorded she burned 16 tons per 24 hours.

Domala returned to Glasgow on 7 December 1921 and began loading and bunkering for her delivery voyage to London. Officially handed over on the 14th, she sailed that day for London and her arrival in the Capital, the largest port in world as it was then, aroused public and press interest. Domala and her sister were heralded as the harbingers of a new era in marine engineering and progress in the post-war age, not bad for just another two otherwise workaday "M"s.

The Domala, except for her machinery, is similar in design and appearance to a number of steamers built for the same owners. ‘These have always proved extremely popular vessels, both with passengers and shippers, as the voyage from London to Bombay takes only a few days longer than the mail steamer, while the price is £10 lower. Passenger accommodation is all amidships, comprising cabins for 41 second class and 85 first class passengers, although arrangements are made by which some of the two berthed first class rooms can be turned into three berthed second class, if desired, increasing the total passenger accommodation to about 140. The engine room is arranged amidships and it is a proof of the quietness and absence of vibration of modern Diesel machinery that the passenger accommodation is all above the machinery, which would not have been allowable were vibration or noise excessive.

Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, 1921

Two of the more overlooked British lines had, nonetheless, proved true pioneers in introducing two of the most consequential developments in motive power to the passenger liner: the steam turbine in 1905 (Allan Line's Victorian and Virginian) and the diesel engine in 1921-23 (British India's Domala and Dumana). Allan Line, had, of course always been at the forefront of innovation but had decided on turbines for Victorian after she had been laid down, whilst British India, hitherto conservative in its ship specification, had diesels in mind for Domala and Dumana at the onset, although they were otherwise all but identical to a much larger class of steam-driven passenger-cargo vessels. But pioneers they were and whilst they showed the promise of the diesel, neither was successful enough to herald the true Motor Ship Age that took root about a decade later.

Here, it should be noted that Domala's bona fides as the first diesel-powered passenger ship built as such, trumps another pioneer, Elder Dempster's Aba (1918/7,937 grt) which had first entered service as a cargo liner, Glenapp, of Glen Line, and rebuilt as a passenger liner by British & African SN Co. in 1920, making her maiden voyage in November 1921.

|

| With all her innovation concealed her engine room, Domala presented an utterly conventional but pleasing profile. Here, she models her P&O-esque livery c. 1925-1935. Credit:clydeships.com |

|

| And for comparison, Dumana with her shorter but larger funnel and lifeboats on the deck at radial davits. Credit: Stephen Card. |

Both were easily distinguished from the other "M"s by having their funnels much further after than on the steamers. The general design was very ordinary, but their lines were good and the fairly heavy rake to mast and funnel gave them a very pleasing and quite elegant appearance.

J.H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, June 1980.

The diesel at sea elicited among some to contrive a "motor ship look" to herald the novelty and modernity of what most could not see below decks. The first seagoing motorliners of East Asiatic Co. were honest enough in simply dispensing with anything looking like a funnel in in favour of exhaust pipes resembling masts instead, but later came all manner of stumpy, squat or even square affairs that proved fashionable enough for a while that some were rather unsuccessfully recreated in steamships. Many, however, took the view that that ships, regardless of how they are powered should look like ships not a factory roof. Funnels had long assumed an almost phalic importance in the image of The Ocean Liner and in some cultures, especially in the Orient, the number as well as size, imparted importance.

|

| Dumana (above) in classic BI livery, c. 1923-25/1935-39. Credit: clydeships.com |

Inchcape, British India and Barclay Curle came to a happy medium when it came to the asthetics of the new Diesel D's... they would look just like their handsome steam-powered fleetmates. Indeed, Domala managed to get a taller funnel than even her Mashobra and Manela predecessors while Dumana's was more like that of the M3's. The layout of the diesel plant, the engine space being but 56 ft. long, meant the single funnel was sited well aft of amidships but the graceful counter stern being less heavy looking that the cruiser design of the M3's and equally pleasing sheer of the hull and rake of the funnel and masts, mitigated the proportional imbalance. Domala and Dumana were pacesetters, but thoroughly pleasing even rakish looking ones.

As single funnel liners, Domala and Dumana also conformed to the prevailing mania for the "modernity" of oil burning ships that had only as many funnels as needed. It was a mode that arose or was rather contrived by Cunard in particular whose epic production of single-funneled "intermediates" like the Scythia-class and a seemingly endless number of similar vessels for Anchor and Donaldsons were so completely opposite of the four-funnelled greyounds before the War as to elicit a publication relations effort to now associate fewer funnels with modernism. How successful it was is illustrated by P&O's Moldavia (1922/16,436 grt), a contemporary of BI's "D"s, which was very modern with her geared turbines and single funnel, but gained a rather awkwardly sited "dummy funnel" by 1928 and BI commissioned Tairea, Takwila and Talamba in 1924... at 7,900 grt they were the smallest three funneled ocean going liners.

|

| Profile plan of nos. 579 and 593 dated 10 May 1919. LEFT CLICK for full size scan. Credit: Lloyd's Register Foundation |

|

| Midship section of nos. 579 and 593, dated 10 May 1919, and already notated "Motor Vessel," LEFT CLICK for full size scan. Credit: Lloyd's Register Foundation. |

The pacesetting Domala and Dumana were only so in their method and means of propulsion, a quality enhanced by their retaining the essential hull form and dimensions of the original Malda of 1913 and not the slightly longer, cruiser stern hull of their M3 contemporaries.

With principal dimensions of 450 ft. (b.p.) length, 464 ft. (overall) length and a beam of 58 ft. 3 ins., Domala had a gross tonnage of 8,441 and 5,125 (nett) and Dumana, 8,427 (gross) and 5,110 (nett).

They each had two overall decks with forecastle, bridge and poop above and the hulls divided by eight watertight bulkheads and a full cellular double bottom sealed for the carriage of oil fuel forward and fresh water aft.

|

| Domala main engine drawings. Credit: Marine Engineer & Naval Architect. |

|

| Domala engine room layout showing the main engines inboard and the separate auxiliary motors and generators outboard. Credit: Motorship. |

|

| Domala side elevation of engine room and funnel. Credit: Motorship. |

|

| Domala cross section of machinery spaces. Credit: Motorship. |

The most interesting feature of the Domala is naturally her machinery, which is entirely of British design and construction, the manufacturers, the North British Diesel Engine Works Limited, Glasgow, having entrusted the entire work of designing the machinery to their own technical staff. The builders are certainly to be congratulated on their achievement, as no other manufacturer of marine Diesel machinery has undertaken at the outset such a high-powered installation.

Marine Engineer & Naval Architect, February 1922

But without further ado... the machinery. Mr. J.L. Leslie, Superintending Engineer of British India S.N. Co. supervised the installation of diesel machinery in Domala and Domana.

In simplest terms, Domala and Dumana were twin-screw ships, each powered by two eight-cylinder single-acting four-stroke engines with air injection with cylinders 26 ⅜ in. dia. and a 47-in. stroke. Each motor produced 2,600 ihp at 96 rpm which gave them a service speed of 13.5 knots. Domala differed in that the air compressors were not driven as customary by the main motors. The compressed air for fuel injection, starting and manoevring was furnished by furnished by two auxiliary Diesel engines driving compressors arranged on the port and starboard sides of the engine room respectively. These auxiliary Diesel engines were six-cylinder four-cycle sets of 400 b.h.p. driving three separate stage vertical air compressors and each set had sufficient capacity for serving both main engines at full power, the other acting as a standbyor for use when an unusual amount of manoeuvring has to be done.

|

| Domala's main engines in the erecting shed of North British Diesel Engine Co, Whiteinch. Credit: Marine Engineering, June 1921. |

|

| One her two 300 shp auxiluary diesels. Credit: Motorship. |

For the technically minded, the American journal Motorship (not to be confused with its British counterpart The Motor Ship) provided a good detailed description of the ship's machinery as well as demonstating the interest they attracted intenationally:

In addition to the two main engines, the Domala has two main compressor Diesel engines. These latter are directly coupled to two three-crank three-stage compressors of the Weir-Murray Workman type, one compressor supplying sufficient injection air for its own Diesel engine plus the two main engines, the other acting as standby. The Domala is 500 h.p. more powerful than the three later Diesel-engined ships of her class or size. This extra 500 h.p. was obtained without any alteration to the main Diesel engines by making the injection compressors independent on the Domala only, so that the main Diesel engines for all four vessels are similar.

The auxiliary generating plant on board the Dumana will comprise two four-cylinder two-cycle Sulzer. type Diesel engines constructed by Stephens, each of 410 horsepower, driving generators of 260’kw. at about 300 R.P.M. These are self-contained with their own air compressors and cooling pumps. There are two electrically driven two-stage air compressors, coupled to motors of 150 horsepower, and the usual electrically. operated bilge, sani- tary, and fuel transfer pumps, in addition to those previously.mentioned. A large proportion of the pumps are grouped together. at the forward end of the engine-room close to the forward bulkhead, the two generators being wee: Aa oe starboard wing. One-maneuvering air compréssor is arranged on each side.

It has been the policy of this firm to standardize their engine sizes, and for this reason it will be found that, in some boats, the injection air-compressors are driven off the main engines, and, in others, separate units are employed. Thus on the Domala, where the maximum shaft horse-power that could be developed by the engine was required, two 400 b.h.p. six-cylinder Diesel sets are employed to drive the compressors. The main engine has thus no accessory pumps of any kind, except the very small ones necessaryfor lubricating the pistons. In the Dumana, where a slightly less speed is desired, the injection air-compressors are driven off the main engines, and auxiliary manoeuvring compressors are driven, one by a 250 b.h.p. electric motor, and the other by a 300 b.h.p. six-cylinder Diesel engine. It is worthy of notice that the auxiliary Diesel engines used for driving the air-compressors are also of the North British Diesel Engine Co.'s own design and manufacture.

Motorship, May 1921

The vessel is driven by twin-screws, each shaft being driven by an eight-cylinder totally enclosed marine type Diesel engine developing normally 2,500 i.h.p. at 96 r.p.m. The cylinders are each 26 in. diam. with a piston stroke of 47 in. These engines have been designed and constructed by the North British Diesel Engine Works at Whiteinch. The fuel injection is on the blast air system and to provide air for this purpose and also for starting up, the engine is supplied by two air compressors which instead of being driven by the main engines are each driven by a separate Diesel engine having six cylinders and developing 400 b.h.p. The auxiliaries are all electrically operated, current for all power and lighting purposes being provided by two large Diesel driven generators, which supply current at a pressure of 220 volts. These engines also have six cylinders and give 300 h.p. on the brake. The engines for driving the compressors and the electric generators have also been supplied by the North British Diesel Engine Works. addition there is a small oil-fired vertical donkey boiler of the "Blake" type, supplied by Beardmore & Co. Limited, and situated on the engine room floor between the thrust blocks which supplies steam for driving a small air compressor for charging the starting bottles if the vessel has been long in port or if for any other reason the supply of air for operating the main compressors should fail. Steam from the donkey boiler is also supplied to the various galleys. In order to tell the height of the fuel and lubricating oil in the various tanks, a system of Teledep indicators have been installed, the gauges being mounted at convenient places in the engine room.

The auxiliary machinery includes two electrically driven CO2 refrigerating sets by Haslam & Co., these being driven by motors each developing 15 b.h.p. at 220 volts, which have been supplied by Newton Bros. (Derby) Limited. The various service pumps, which have been supplied by Carruthers Limited, are also electrically driven, the motors and the control gear having been supplied by Electromotors Limited. Special attention has been paid to the design and construction of the control gear in order to render it absolutely safe and as far as possible fool proof." The starting resistance is operated by a small hand wheel so that the resistance coils can only be cut out very slowly. The deck machinery, comprising cargo winches, windlasses, &c., is also driven by electricity. The cargo winches are by Clark, Chapman & Co. and are driven by electric motors of about 50 h.p. operating through Williams-Janny variable speed gear. The motors are operated on the 220 volt circuit at a maximum current of 165 amps. The lifeboats are made of steel and operated by Welin davits, which in addition to being worked by hand can be worked from a special winch of which there are two, one being mounted on each side of the boat deck.

Shipbuilding & Shipping Record, 29 December 1921.

|

| One of the many features on Domala in the American shipping press. Credit: Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, 1921. |

Mr. Angus Murray, of Messrs. G. and J. Weir, Ltd., who were responsible for the installation the air compressors, awaited the arrival the at Plymouth, the Murray-Workman patents having been taken over by Messrs. Weir, who specialize Diesel auxiliaries. Mr. Murray pointed out special feature of the ship, the main air compressors being driven by Diesel engines which are quite apart from the main engines. The result, he said, has been to give greater shaft horse-power and consequently higher speed. As much as two knots represented the ease of the Domala, which has the biggest compressors for the highest pressure ever made in Europe. The machines are capable compressing 1,000 cubic feet per minute at pressure of l,000 lbs.

Western Morning News, 21 March 1922

The reason cited for the arrangement in Domala was to extract the maximum horsepower from the main engines for propulsion. Yet, her 13.60 knots achieved on trials compared with Dumana's speed of... 13.56 knots. All of the extra machinery packed into the 56-ft. long engine compartment had, it proved, no material effect on horsepower produced or speed obtained. It did prove to be Domala's achilles heel from the onset and her machinery was notoriously unreliable, made worse by the fact that all of the steering, winches and auxilaries... even the galleys were electrically powered. Engine breakdowns could render the vessel suddenly without power steering and other essentials and she was notoriously unreliable in docking manoveuvers. It was not uncommon to have tugs bring her into harbour not merely assist in bringing her alongside.

|

| Top platform. Credit: Motorship. |

|

| Upper platform. Credit: Motorship. |

|

| Lower platform between the main engines. Credit: Motorship. |

|

| Lower platform showing engine control panel. Credit: Motorship. |

The claims of economy with diesel propulsion was realised with oil consumption working out to 18 tons a day or as it was usually calculated, 0.42 lbs. per bhp. The coal-fired "M"s burned 70 tons a day or 45 tons of oil by comparison. Both ships could carry sufficient fuel in their huge double bottom tanks sufficient for the 13,000-mile roundtrip which was just as well give the comparative scarcity of diesel fuel bunkering facilities en route although these came in time at Aden. "It is worthy of note as indicating the economy of operation of the Diesel driven ship that the entire engine room staff comprises 28 men, including an electrician and 15 greasers, as compared with about 66 men, including the engineers, greasers, and stokers required on a similar steamer with coal fired boilers. The use of oil fuel for steam raising purposes would, of course, lead to a reduction in the number of men required." Shipbuilding & Shipping Record, 29 December 1921.

Cited in reference to Dumana specifically was provision to mitigate mud and debris being induced into the sea water system that cooled the engines, a real factor in Indian ports and especially Calcutta which was at the mouth of the muddy Hooghly River.

As the Dumana is liable to enter rivers which are extremely muddy and there is a possibility of a considerable amount of deposit being drawn through the circulating system, ar- rangements are made whereby the piston cooling pumps draw the sea water through a special tank provided with filters. The main reason why some Diesel engine manufacturers (as, for instance, Harland & Wolff) employ fresh water cooling for the pistons is because of this danger of muddy water and not on account of the possibility of salt being deposited in the cooling spaces in the pistons as is sometimes imagined.

Marine Engineering/Log, May 1923

The British India Steam Navigation Co., after some early and rather unfortunate experiences with oil engines, has not repeated them in later programmes of construction, although new War Office transport construction, it is whispered, has for some time been considered with diesel propulsion.

A.C. Hardy, Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 25 October 1934

Domala had rather a dismal record mechanically it will be admitted and only after a comprehensive overhaul and reworking of her engines and auxiliaries at North British Diesel Engine Works, did she settle down to a reasonably reliable subsequent career. Dumana, with her more conventional machinery arrangement, was spared her sister's mechanical mishaps. Durenda, essentially a cargo only version of the two, which was completed in September 1922 and with the same machinery as Dumana, lasted in wide ranging BI service until May 1956 and sold for further trading, not scrapped until 1960. But BI's first foray into diesels was not a success in that it was not repeated until Dilwara (1936) and Dunera (1937) which were troopships and powered by the Doxford opposed piston design diesel that really established The British Motor Ship and would go on to power BI's famous "C" class of cargo-passenger ships and latest class of BI since the "M"s. Still, the company went back to steam turbines for all of its final large liners: Karanja, Kampala, Kenya, Uganda and its final troopship, Nevasa.

It should be noted, too, that BI's experience with the early marine diesel was by no means unusual and when the Depression set in, a good proportion of those ships laid up were indeed so-powered, including Domala and Dumana.

Like her "M" class sisters, the "D"s had enormous cargo capacity for their size with some 11,125 tons deadweight capacity (516,000 cu. ft. including 1,000 cu. ft. refrigerated) which was carried in six holds:

No 1. 60.6 ft. long 22.6 x 18 ft. hatchNo 2. 54 ft. long 27 ft x 18 ft. hatchNo 3. 74.6 ft. long 29.3 ft. x 18 ft. hatchNo. 4 61 ft. long 22.6 ft. x 18 ft. hatchNo. 5 49.6 ft. 22.6 ft. x 18 ft. hatchNo. 6 54 ft. 22.6 ft. x 18 ft. hatch

True enough, the much smaller "footprint" of their machinery spaces made no. 3 hold's tween decks that much larger than their steam compatriots. All the holds had heavy under-deck girders and widely spaced pillars to maximise capacity. In terms of cargo handling, the "D"s duplicated Mashobra and Manela with two 4-ton derricks for each hatchway, those for no. 1 swinging from a short single port with a wide crosstree, distinguishing them from the other "M"s. A 30-ton derrick was fitted to the foremast and a 14-ton one on the mainmast. Thirteen electrohydaulic winches were fitted.

The boatage, all made of steel, comprised two 60-person 30-ft. and two 50-person 28-ft. lifeboats and one 20 ft. dinghy, at Welin davits raised off the deck in Domala but for some most curious reason, Dumana was fitted with old-fashioned radial davits with her boats flat on the deck, robbing her of that much more deck space and not enhancing her appearance, either.

M/v DOMALA

Profile & Deck Plan

Credit: Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, February 1922.

LEFT CLICK on image for full scan.

|

| Profile & Rigging Plan. |

|

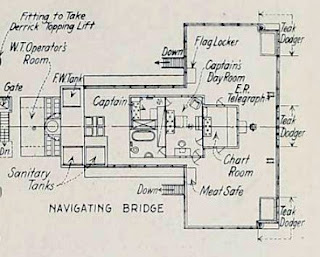

| Navigating Bridge. |

|

| Boat Deck. |

|

| Promenade Deck. |

|

| Poop and Forecastle Decks. |

|

| Bridge Deck. |

|

| Upper Deck (detail showing passenger accommodation). |

|

| Upper Deck. |

|

| Main Deck. |

The Domala has accommodation for about 140 passengers, comprising 100 first-class and 40 second-class. The accommodation comprises single and two-berth cabins for the first-class passengers, with double and four-berth cabins for the second-class. In addition to the saloons, which have been tastefully decorated, there are a smoking room, music room, lounge, & etc., all of which have been furnished in a style which suggests great comfort without over elaboration. The passenger accommodation is well ventilated by means of electric fans, and electric radiators are provided in each cabin for use in cold weather.

Shipbuilding & Shipping Record, 29 December 1921

Despite their small size and large cargo capacity, Domala and Dumana, like their sisters "M"s, were proper passenger liners with quality appointments, quietly comfortable surroundings and pleasant decor and furnishings. The accommodation, too, was on par with other colonial mailboats and the all outside cabins a much appreciated selling feature. Although initially two classes, their First Class was without pretension and on the Indian run, especially, their lack of the rigid social hierarchy and burra sahibs of the big Bombay Mail steamers made them extremely popular, not to menton their lower fares to compensate for their leisurely pace.

The layout of these ships was as straightforward as any built. The Boat Deck was devoted entirely to officers' accommodation (save the captain's stateroom which one deck above adjoining the bridge) with deck officers, cadets and wireless officers quartered in the fore house and engineers aft together with their own mess. All of these cabins had jalousie doors opening directly onto the outside deck and large windows. Combined with the extensive outside deck space (although Dumana's was more restricted with her lifeboats on the deck rather than carried over it as on Domala), this was really exceptional accommodation for the era.

Lord Inchcape who is chairman of the British India Steam Navigation Company, holds strongly to the view that engineers and deck officers should have the best possible accommodation and moreover that they should be located on the same deck. In the Domala, therefore, both the engineers and the navigating offiers are berthed on the boats deck, the former at the after end and the later forward, a separate room being provided for each deck officer. It is to be noted that by this system, the engineers and the deck officers have a large space for recreation purposed, exclusive of the passenger deck.

Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, 1921

Promenade Deck was entirely given to public rooms and covered promenade space with the forward two-thirds First Class and the aft third, Second. The First Class music room was forward, then the entrance and main staircase and smoking room. These rooms both featured large bays with brass framed 24" x 18" windows which formed seating alcoves. Amidships the covered promenade was deep enough to permit outdoor dancing in fair weather. Aft was the Second Class smoking room and music room sharing the same deck house and entrance and stairway and its share of promenade deck.

Bridge Deck was all accommodation for First Class (forward) and Second Class (aft) which had a block of cabins interchangeable between the two, being let as four-berth as Second Class or three-berth as First. All had large windows and shaded from the sun by the covered promenade deck encircling the deck, were the most desirable cabins. "The windows of all these cabins open on to the sheltered promenade space of the bridge deck, a feature which practised voyage will appreciate." (Blue Peter).

Upper Deck had the First Class dining saloon forward and that for Second Class aft with First Class accommodation forward and Second aft on the starboard side. These were all outside cabins and designed on the "Inchcape" patterns introduced by the first of the "M"s, Malda, in 1913 whereby otherwise inside cabins had a porthole accessed via a narrow passage to the side of the ship, the idea being to induce daylight and, most importantly, ventilation.

All of the cabins are provided with a port-hole. An examination of the plans show in the case of the interior cabin this has been carried out in a very ingenious manner by leaving a passageway between the two outer cabins. In this way, a certain amount of space is lost but there is undoubtably an overwhelming advantage in its favor. The system was introduced by Lord Inchcape and a somewhat similar method is adopted on certain other British passenger liners.

Marine Engineering & Shipping Age February 1922.

|

| Domala First Class Music Room. Credit: Historic England. |

|

| Dumana First Class Music Room. Credit: Historic England. |

|

| Domala First Class Smoking Room. Credit: Historic England. |

|

| Dumana First Class Smoking Room. Credit: Historic England. |

The Music Room was, according to The Blue Peter, "curtained, carpeted and furnished in a style which combines daintiness with a high degree of comfort and convenience, whilst of the Smoking Room, it was described as "more sober in its appointments and perhaps more solid in its comfort,' and of "a character likely to be viewed by old travellers with an appreciation born of experience." Each ship had its own distinctive decor for the First Class rooms, Domana having perhaps the more pleasing of the two.

|

| Domala First Class Promenade Deck looking forward. Credit: Historic England. |

|

| Domala First Class Promenade Deck showing the characteristic bay windows of the music room and smoking rooms. Credit: Historic England. |

|

| Dumana First Class Promenade Deck, photographed in July 1927 after BI ships adopted the P&O livery of brown superstructure. Credit: Historic England. |

|

| Dumana First Class Promenade Deck looking forward, July 1927. In a few years, the class barrier would be removed when the ships became one-class. Credit: Historic England. |

Both Promenade and Bridge Decks had wide covered promenade decks and that on Promenade Deck was wide enough for dancing. Here, it should be noted that dancing, indoors, on British colonial mailships was "not the done thing" up to the Second World War and none of the indoor rooms had dance floors. Outdoor deck space was minimal with that on Boat Deck reserved for officers whose accommodation was situated and there, but given the ships' route, few sought out the sun in any event.

|

| Domala First Class Dining Saloon. Credit: Historic England. |

|

| Dumana First Class Dining Saloon. Credit: Historic England. |

|

| Dumana First Class Dining Saloon, looking forward. Credit: Historic England. |

"At the forward extremity of the upper deck is the first-class dining saloon, seating, at restaurant tables, 84 passengers, and lighted on three sides by fifteen large windows. This saloon is decorated in white enamel and furnished with anchored Hepplewhite chairs in pale oak the whole effect being cool and pleasing." (The Blue Peter).

|

| Summary of Accommodation for Domala. Credit: Motorship. |

|

| Domala First Class single cabin. Credit: Historic England. |

|

| Dumana First Class single cabin. Credit: Historic England. |

|

| Dumana First Class two-berth cabin. Credit: Historic England. |

The passengers accommodation of the Domala is all situated in the midships portion of the vessel's length on the three decks, above the main deck; she has no inside rooms, the cabins being all of the kind known as the Inchcape tandem type, each provided with access to the outer air and receiving natural light by means of its porthole. Each cabin of either class is provided with continuous water supply, electric fans, electric light, wardrobes or drawers, toilet mirror and other usual fittings, and there is for each berth or bed an electric reading light.

The Blue Peter.

First Class accommodation on Bridge Deck (amidships to forward) comprised eight single-berth cabins, 12 two-berth and two three-berth cabins and on Upper Deck, five three-berth cabins portside forward and three three-berth cabins starboard. In addition, there were an additional 23 berths that were interchangeable with Second Class, aft on Bridge Deck. All cabins have running water and electric fan and electric heat. "All of the cabins are provided with a port-hole. An examination of the plans show in the case of the interior cabin this has been carried out in a very ingenious manner by leaving a passageway between the two outer cabins. In this way, a certain amount of space is lost but there is undoubtably an overwhelming advantage in its favor. The system was introduced by Lord Inchcape and a somewhat similar method is adopted on certain other British passenger liners." (Marine Engineering & Shipping Age, February 1922). Sometimes referred to as "The Bibby Cabin," the Inchcape design was introduced with Malda in 1913.

Of Dumana's accommodation, Marine Engineering of May 1923 wrote:

The passengers are berthed in cabins on the upper and bridge decks. Normally there 1st accommodation for 88 first and 41 second class passengers, but as is usual with the British India Steam Navigation Company’s vessels of this class, some of the cabins can be altered so that the number of first class passengers carried may be increased or diminished as required. They are mainly two and three berth cabins, all arranged with direct access to the side of the hull, so as afford natural lighting in each room, At the forward end of the upper deck is the dining saloon with a large number of small tables, and at the after end is the second class dining saloon. Forward of the promenade deck is a first class music room and a separate smoking room, while aft is the second class smoking room. Officers and engineers are both berthed on the boat deck, the latter being at the after end. This system of having the engineers and officers on the same deck was one of the innovations of the British India Steam Navigation Company, some years ago, and is now very popular.

"At the end of this deck is the dining saloon of the second-class, naturally lighted on three sides, seating 74 passengers, handsomely furnished in mahogany."

"On this deck also are the music and smoking rooms of the second-class, not so spacious nor so elaborately appointed as those of the first-class, but of size and appointments which will amply meet the needs of the smaller number to whose use they assigned." (Blue Peter)

Second Class accommodation comprised 24 berths aft on Bridge Deck and 17 berths on the starboard side of Upper Deck aft, all in outside cabins with running water.

The similar appointments and all-outside feature of Second Class accommodation facilitated an easy and beneficial conversion of Domala and Dumana and, later, their fellow "M" class fleetmates, into one-class ships in 1929, accommodating 111 Cabin Class passengers respectively and increased to 138 (Domala) and 140 (Dumana) in 1934. The First Class dining saloon was re-arranged to seat 70 diners per sitting and the former Second Class saloon converted into a card room and children's nursery and dining room while the Second Class music room and smoking room was combined in a large and attractive veranda lounge with light panelling, wicker furnishings etc.

Domala and Dumana were thoroughly well-found, comfortable and handsome liners, and with the other "M" class vessels hold down all of the Home Line services to India and East Africa throughout the inter-war era. Yet, all eyes were on "The Diesel Ds" upon their entry into service as harbingers of a new and promising Motor Ship Age.

|

| Imperial Partners: Dumana and Moldavia. Credit: The Blue Peter, November-December 1922. |

Although we have had to wait a long time for the first motor passenger liner to make its appearance, it will now probably not be long before it is completed. The twin screw machinery is being installed in the motor passenger liner Domala, for the British India Steam Navigation Company, and shipowners and shipbuilders are watching this ship with the very greatest interest, as it is realized that a great deal depends upon its satisfactory operation.

Marine Engineering, June 1921

A British India liner loading in the Royal Albert Docks, something so much a part of the London docks scene as to be an everyday occurance, had never quite so aroused as much interest and public and press attention, as that attending the brand new Domala in June 1921. More than a capacity passenger list and cargo manifest was literally riding on her as she began her career with her maiden voyage to Bombay that summer.

Great interest centres round the British India liner Domala, which has just arrived in the Royal Albert Dock to load for her maiden voyage, as the first motor passenger liner to be intended as such from the first.

She appears to be an ordinary comfortable 8,000-ton passenger steamer, for the exhausts from her engines are led up through a big funnel.

It is only the unusual absence of smoke which distinguishes her from her steam sisters.

Two of these, the Modasa and the Mantola, are lying near her preparing for a very thorough series of sea tests to prove the relative merits of turbines and motors for passenger work.

Nottingham Journal, 23 December 1921

Domala was opened to inspection by invitation on 22 December 1921 whilst lying in Royal Albert Dock, London.

MOTOR PASSENGER LINER. To-morrow motor ship Domala sails from London her maiden voyage, an event of considerable importance to the shipping community. She is the first, motor passenger liner to sail from London, is the second vessel of her class completed, and the first oil engined craft which was specially designed for passenger carrying, the previous vessel, the Aba, having been converted from a cargo boat. She is, moreover, first motor ship to built for the British India Steam Navigation Company, and what is perhaps more important, she is similar in all respects except machinery to numerous other vessels now in service for the same owner. Some of these are provided with reciprocating engines, others with geared turbines, and while some the steamers have oil-fired boilers, others are designed to bum coal. The vessels will be operated on similar routes, so that the conditions will be almost identical in every respect. Although there is little difference the weight of the machinery the motor ship and the steamer, the oil engined vessel starts with the initial advantage of a larger deadweight capacity. The comparative results will he the mora valuable as some of the steamers have only recently been completed and are fitted with the most modern and efficient machinery, having low a fuel consumption any vessels of their size now in service. The results achieved by the Domala may possibly have important bearing on motor ships of the future, and her performances will therefore be watched with interest.

Western Daily Press, 29 December 1921

Racing East

The British India motorship Domala and her turbine-driven sister Modasa each left the Thames by yesterday's tide, the former bound for Bombay and Karachi, and the latter for East Africa. Not only is there the factor of sister hulls being given different types of machinery, but there is the even more important point that the motorship was built by Barclay Curle on the Clyde, while the steamer hails from Swan Hunter's Tyneside yard. It may be that instructions will be given for the careful nursing of the Domala's diesels, but she did so well on trial and the motors proved themselves so reliable on fairly stiff tests through which she passed, that this is not by any means certain. For against the advantages of nursing new engines is the very great advantage of pride of ship, a feeling which the P. and O. and associated companies know how to encourage as well as anybody.

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 31 December 1921

Marking a milestone in the development of the diesel-powered liner and beginning what would truly be the Motorship Era of the 'twenties, M.v. Domala (Capt. W.E. Whittingham, Chief Engineer P. Robertson) sailed from London's Royal Albert Docks on 30 December 1921.

|

| Commander W.E. Whittingham and his officers for Domala's maiden voyage and the first for a new diesel-powered liner. Credit: eBay auction photo. |

If British India's variously powered "M" class might provide the engineer minded a fair comparison as to their respective merits, having the diesel-driven Domala and the turbine-propelled and coal burning Modasa leave London on the same tide on 30 December 1921 gave some in the press the more exciting prospect of a veritable "race" between the two and which would reach Aden first before they diverged on their respect courses to India and East Africa respectfully. The Hampshire Advertiser (as good as any paper in the land when it came to ocean liners) of 7 January 1922 reminded its readers that "at Port Said the Modasa will be held up for one day while her coal bunkers are being replenished, which will allow the Domala a useful start. On the other hand, the motor-ship cannot exert her engines too much owning to their newness." 'We are watching the progress of the two ships with the utmost interest,” said official of the company. are quite satisfied, as result of the trials, that the Diesel engines ran very well, and give every promise being as reliable as turbine engines.At the end of the present, voyage we shall, however, better able judge how far our experiment has been justified.'

"The vessel left the Thames on December 30, and before they reached Gibraltar the Domala had already gained a day's time, which she did not lose for the rest of the run." (Glasgow Herald, 19 January 1922). Disappointing those wanting a close-run race but proponents of the motor ship, Domala arrived at Port Said on the 11th and passed out of Suez on the 13th and Modasa reached Port Said on the 12th and Port Sudan on the 16th. Domala arrived at Bombay on the 27th "practically at the scheduled hour," in 22 days. Moreover, her fuel consumption at 13.5 knots worked out to under 17 tons a day "or one-fourth only in weight of the coal equivalent."

The twin-screw motor passenger vessel Domala, owned by the British India Steam Navigation Company, has made a most successful voyage to Bombay, and is now on her way homeward. Her passengers speak in most enthusiastic terms of the vessel, and her performance, both as regards speed and economy of fue, has been extremely gratifying to both owners and builders.

Glasgow Herald, 17 February 1922

Homebound, Domala arrived at Karachi on 16 February 1922. Departed on the 17th and Bombay on the 19th. Leaving Bombay on the 23rd, transiting the Suez Canal on 6 March and on the 20th she came into Plymouth at 7:30 a.m. to land 96 passengers, before proceeding on her usual cargo working ports of Antwerp (5,749 tons landed there), Hamburg (3,444 tons) and Middlesbrough (1,600 tons). She reported fine weather throughout the voyage save for fog in the Channel. The excellent shipping page of the Western Morning News provided an extensive write-up of the voyage:

The Domala, the British India liner, which came into Plymouth Sound yesterday for the first time, is on her maiden voyage. This in itself is matter of interest, but the Domala, although she not one of the great show ships of the world, has great deal demand the attention of the public, she is the first vessel designed as a motor passenger liner.

Driven by oil, the ship has many advantages of which the passengers who disembarked at Plymouth yesterday talked freely. There are no vexatious delays at ports coaling ship and, of course there a conspicuous absence the dirt and confusion always attendant on coaling operations. At a speed of 13½ knots, the Domala's daily consumption oil is under 19 tons —one fourth only in weight of the coal equivalent—and consequently in her cellular double-bottom the Domala can carry enough fuel oil for a round trip from London India and back.

The passengers at Plymouth were enthusiastic their praise of the Domala, and they insisted that the officers had made every effort to make her 'a popular ship.' The spontaneous tributes entered in a passenger book by those who travelled out or home in the Domala constitute lasting testimony the comfort and happiness which prevailed in the vessel, which promises to become great favourite in the Eastern trade. Already a good part of the Domala's passenger accommodation for her second trip Bombay May has been booked.

There is, of course, addition to the special character of the ship, an added attraction of the lower scale of saloon passenger money ruling steamers of the British India Company's Bombay line.

UTILITY OF THE ENGINES. Captain W. E. Whittingham, who has command of the Domala, told our representative that the trip out and home had been most successful. The internal combustion engines," said, ran smoothly as if they had been sewing machine." Captain Whittingham is convinced of the utility and efficiency of the type engines. mentioned as an instance of their adaptability that the space of seven seconds is sufficient to stop them working full speed astern from full speed ahead. At 13½ knots she will stop dead in four minutes, so responsive is tbe ship to her motors. The chief engineer, Mr. P. Robertson, who has had charge the wonderful twin engines of the Domala, stated that the machinery, which was constructed at the North British Diesel Engine Works, has proved highly economical. are bound," he remarked, ' save a couple thousand pounds more on tho fuel consumption each trip.'

SHIP'S SPECIAL FEATURE. Mr. Angus Murray, of Messrs. G. and J. Weir, Ltd., who were responsible for the installation the air compressors, awaited the arrival the at Plymouth, the Murray-Workman patents having been taken over by Messrs. Weir, who specialize in Diesel auxiliaries. Mr. Murray pointed out special feature of the ship, the main air compressors being driven by Diesel engines which are quite apart from the main engines. The result," said, 'has been to give greater shaft horse-power and consequently higher speed, as much as two knots represented the case of the Domala, which has the biggest compressors for the highest pressure ever made in Europe. The machines are capable compressing 1,000 cubic feet per minute at pressure of l,000 lbs.

COMFORTABLE ACCOMMODATION. The Domala on her present trip has 10,813 tons cargo, but actually she has accommodation for 11,125 tons, in addition to 158 passengers, who are provided for the midship portion of the vessel on the three decks above the main deck. Cabins are so arranged that there are no inside rooms, each cabin having access to the outer air and receiving natural light means its own porthole. Each room either class has continuous water supply. public rooms are cosy and comfortable. There single-berth cabins and two-berth cabins, as well as " family " cabins, the Domala caters for first and second class passengers

Western Morning News, 21 March 1922

Upon her return home, newspapers reported that a cost savings of £2,000 had been realised on fuel during the round voyage over a comparable trip burning coal. It had been, by all accounts, a successful maiden voyage and a well-publicised one, certainly for a British India liner.

In March 1922 the keel of Domala's sister was laid at Barclay Curle as no. 593. Originally to have been named Melma, she would soon, instead, be known and launched as Dumana.

All this renaming of ships, which had been far more unusual prior to the War, had once been both uncommon and considered unlucky by notoriously superstitious sailors. Whereas Dumana had been renamed prior to launching, which exempted her to the "jinx" as her subsequent career proved but Domala, alas, had indeed tempted fates, and proved rather a "hoodoo ship" in the BI fleet and at the onset of her career, indeed before her first voyage was over.

Coming into Antwerp docks from Plymouth on 23 March 1922, Domala had a serious collision with the outbound Finnish steamer Pallas (1921/1,466 grt). Domala, reported to be "badly damaged aft," Pallas' icebreaker bow penetrating as far as her keel aft, made it into port as did Pallas.

|

| Domala at Antwerp, 23 March 1922 following her collision showing the damaged to her stern. Credit: Louis Claes photograph, Nationaal Scheepvaart Museum |

Scheduled to sail from Middlesbrough on 21 April 1922 and from London on 5 May on her second voyage, Domala was not going anywhere and, instead, underwent extensive and prolonged repairs in Antwerp which fortunately had excellent drydock facilities and, indeed, was used for overhauls by British India already.

It was not until 16 September 1922 that Domala resumed service upon arrival at Middlesbrough to load for the outward voyage. Coming into London on the 23rd, she sailed from London on the 29nd, on BI's other Home Line to India, that to Calcutta, via Colombo and Madras. Transiting the Suez Canal 9-10 October and calling at Aden (16) and Colombo (24), Domala called at Madras 26-29th, sailing on the 29th for Calcutta where arrived on the 31st. Of all BI's regular ports, Calcutta, its port situated at the mouth of the muddy Hooghly River, was the greatest test of Domala's diesel machinery, specifically her injection system for her water-cooled diesels which had been specially modified for such conditions. As it was, she was there until 23 November when, fully laden, she sailed for home, calling at Madras (26-27), Aden 6 December, Suez (11), Marseilles (18-19) and arrived London on the 27th. From there, she sailded for Antwerp and Hamburg to complete her cargo unloading.

|

| Credit: The Scotsman, 22 November 1922. |

Being "the second sister," Dumana's launch at Barclay Curle's Clydeholm yards, Whiteinch, was attended with the scant publicity afforded most British India ships. She was sent down the ways on 21 November 1922 and if afforded a christening, by whom was not recorded. It was still a milestone in BI history being the last of the "M" class ships to be launched, and the last new Indian Home Line passenger vessel to be completed.

1923

After her one voyage to Calcutta, Domala would be back on the Bombay/Karachi run, sailing from London 2 February 1923 and arriving at Karachi on 4 March and Bombay on the 13th.

Dumana ran trials 16 March 1923 on the Skelmorlie measured mile and had aboard for the occasion, Mr. Islay Kerr, Capt. Hodgkinson, Mr. Leslie, and Mr. Brown and representing the builders, Mr. Noel E Peck, Mr. Archibald Gilchrist and engineers, Mr. C. Randolph Smith. "Probably the most notable vessel completed on the Clyde this year... The ship is designed for a sea speed of 13 knots, but on trials this speed was exceeded by about one knot." (Shipbuilding and Shipping Record, 22 March 1923).Actually, her speed on her extended trials was 13.56 knots. She arrived at London on the 31st.

Dumana was the 20th passenger vessel commissioned for BI in ten years, rising the combined fleet to 156 vessels totalling 867,927 gross tons.

NEW MOTOR LINER. The British India Company's new motor passenger vessel Dumana left London to-day on her maiden voyage to Bombay. Of 8,600 tons gross, she is a sister of the same company's motor ship Domala. The Dumana has accommodation for 158 saloon passengers, and has been especially equipped and furnished for the Indian passenger services. in which she will chiefly be employed. Her public rooms are large, pleasingly and comfortably furnished.

Pall Mall Gazette, 11 April 1923

The new motor-driven liner Dumana which has just left the Thames on her maiden voyage to India, attracted a good deal of attention.

Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 12 April 1923

Commanded by Capt. H. Stockwell, Dumana sailed from London on 11 April 1923 for Malta, Port Said, Suez, Bombay and Karachi. Malta was reached on the 20th, Port Said on the 24th and transiting the canal, left Suez on the 25th, touched at Aden on the 30th and arrived at Bombay on 6 May and finally Karachi on the 17th. Homewards, Dumana sailed from Karachi on the 23rd, Bombay on the 25th, called at Aden on 1 June, transited the Suez Canal 6-7th and after pausing at Malta on the 11th, coursed towards Plymouth where she was expected on the 19th but did not arrived until the following morning owing to stormy weather in the Western Mediterranean and again off the coast of Portugal. She landed 129 passengers and 126 bags of mail. Dumana was off by 9:00 a.m. for Hamburg and Middlesborough with her 8,112 tons of cottonseed and 2,500 tons of ore.

Meanwhile, all was apparently (if never publically reported) not at all well with Domala. She arrived at London from Bombay and the usual ports on 9 April 1922 and left for Hull on the 11th to commence her round of cargo unloading ports but never made her scheduled sailing from Middlesbrough on 21 April 1922 and from London on 5 May on what would have been her third voyage. Instead, on 8 May she was reported to have arrived at Falmouth. There, the dry dock and shipyard of Silley, Cox & Co., had long been used by P&O/BI for overhauls and periodic lay-ups and it is presumed that Domala was there for repairs, it not being likely an almost brand new vessel with but three voyages to her credit would be otherwise idled. Regardless, she disappeared from the sailing lists for much of the remainder of the year.

Dumana's second voyage would trial her on the Madras and Calcutta run. Departing London on 15 September 1923, she cleared Suez on the 28th, Aden on 4 October and Colombo (12), making her maiden calls at Madras on the 16-18th and Calcutta on the 20th. She sailed for home on 5 November via Madras (7), Colombo (12), Aden (20), Suez (25), Port Said (26) and Marseilles (2 December. After "a strong head gale was experienced as Ushant was approached," (Western Morning News), Dumana arrived at Plymouth at noon on the 9th, landing 42 passengers. A heavy cargo was discharged at London on the 10th (2,953 tons), Hamburg (1,499 tons), Antwerp (1,848 tons) and 2,250 at Middlesbrough.

Finally back in service (on the Bombay/Karachi run), Domala arrived at Middlesbrough on 21 October 1923, Antwerp on 5 November and London (Royal Albert Dock) on the 13th. Ten days later, she departed for Bombay (17 December) and Karachi where she arrived on the 28th. Homewards, Domala returned to Bombay on 5 January 1924 for loading and sailed on the 11th and after calling at Aden on the 17th, arrived at Suez on the 22nd. There, "delayed by damage to dynamo," she did not begin her transit of the Canal until the 23rd, and reached Port Said on the 24th, not departing there until the 26th. Calling at Malta on the 31st, she finally arrived at Plymouth on 9 February (being expected on the 8th) in company with Madura, in from Calcutta. There, Domala experienced "engine trouble" and detained there for repairs before proceeding to Antwerp.

By then, Domala had already acquired a "reputation" in the fleet, even among the most junior of officers as later recounted by then 4th Officer A.E. Baber:

I, did, however pass [Board of Trade Examination for cadet to become an officer in 1923] and was assigned to a ship, the M.V. Domala, as fourth officer.

I have made previous mention of the infancy of the diesel engine and that my company, the British India Company, were pioneers in converting their ships to this form of propulsion. The Domala was one of these 'modernised' vessels and there were many occasions when wondered if we would ever reach our destination before our engines gave up. In fact, one or other of the main engines had to be stopped nearly every day in order that repairs could be carried out.

Not only were the engines diesel but we also had diesel generators that powered our auxiliary machinery. On the occasions when these failed we had to change over, very quickly, to hand steering.

We became very practised at dining by candlelight due to the electricity failures but other duties became onerous when we were suddenly left with no controls over the ship's movement.

On particular Sunday when the captain was holding church service I was left on watch on the bridge. Before I had experienced any great pleasure in the realization that I was in command the steering gear broke down and we executed a complete circle around another ship. We finally connected the emergency steering but it was a shame-faced fourth officer that had to bear the captain's wrath and no amount of explaining would pacify him.

Our ship was so unreliable that on approaching some port we were not allowed to use our main engines for manoevering but had to employ additional tugs to tow us into dock.

These frequent mishaps did have their lighter side for once, when we had passed through the Suez Canal, our engines again left us down and we were nearly a week repairing them. The passengers amused themselves by bathing and playing hockey on the sands at Port Said. They were also able to go ashore for sightseeing excursions and small motor-boats could be hired for this purpose from the gangway.

One of the passengers, a rather formidable lady, decided she would take advantage of this unscheduled stop and hired one of the motor-boats to go ashore. The lady, accompanied by her daughter, was gallantly helped into the launch and both settled back to enjoy the view.

The configuration of our ship was such that it had an overhanging counter stern and the coxswain of the launch, believing it the shortest route, decided to pass closely under this. All should have been well but at this very moment that the crews latrine, which was house in the over-hanging stern, was discharged, covering the two abject ladies from head to toe.

The launch immediately turned around and made back for the gangway with its now odoriferous occupants. As the two dedraggled figures slowly climbed the gangway they were met by the officer of the watch whose training, while being extremely comprehensive, did not cover all eventualities. As the ladies approached him he suddenly became aware of their plight and of the smell that accommpanied them so much that he blenched and took a step backwards. The stench was indescribable and the language even worse and most unbecoming for persons of their background. Fortunately they were wearing wide brim sun hats and so were spared a certain amount but as they slowly walked along the deck to their cabin a passage-way was quickly made by crew and passengers alike.

Voyages and Fragments, A.E. Baber, 1985

|

| Domala when new. Credit: Stephen Card. |

1924