She fulfilled the omen, 'unlucky the ship that refuses to leave the ways.'

Nancy Y. Middleton (daughter of Capt. T.F. Smellie),

Times Colonist, 18 August 1985

Superstition has been the disposition of many a mariner since ancient times and woe to the vessel that earns the reputation of being unlucky, especially at her baptism in her natural element at her launching.

When the Hudson's Bay Company had her built in Scotland, she was inspired by an ancient tradition, coming shortly after their 250th anniversary and buoyed by the booming business of The Roaring Twenties. The largest and finest ship ever commissioned for HBC, she had it all-- looks, specification, the toughest hull and most advanced navigation aids to ply some of the most dangerous waters in the world-- the True North of Labrador, Hudson Bay and Baffinland, following in the wake of her legendary fleetmate Nascopie.

But when christened in honour of Hudson's Bay Co.'s first Governor, she did not move an inch off the ways. After two more failed attempts, she finally went into the water with such force as to damage her hull. Seemingly adverse to water at birth, she was a "Hoodoo Ship" to satisfy the most superstitious seaman. Truly "damned by destiny," she would not complete her second voyage, a victim not of the ice she was designed to withstand but of rock.

This is the story of a fine yet fated flagship…

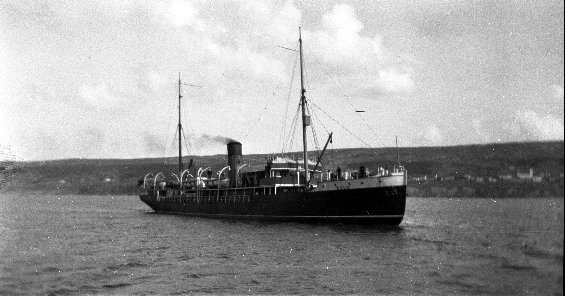

H.B.S.S. BAYRUPERT (1926-1927)

.jpg) |

| A German cigarette card seems to be the only colour depiction of the shortlived Bayrupert and the funnel should be plain buff! Credit: eBay auction photo. |

Let me remind you, in passing from this subject of transport, of the wonderful continuity of your Company. Think of it, if you please—258 years ago, on June 3, 1668, our first proprietors dispatched the little Nonesuch, with forty-two souls on board, for the discovery of the northwest passage and to 'find a trade for furs, minerals, and other commodities.' With very few exceptions, owing to wars in the earlier years, we have been sending out our annual venture ever since, and from 1726 not a year has passed without a ship of the Hudson’s Bay Company sailing for Hudson Bay. And so it was, with a justifiable pride, that on June 3, 1926, we celebrated these two centuries of continuous sailings by dispatching the steamer Bayrupert—a vessel seventy times as big as the little Nonsuch, and fitted with every modern device for safety and reliability—upon the road which we have followed so long and so persistently.

HBC Governor Mr. Charles V. Sale,

General Court of the Governor and Company of Adventurers

of England Trading into Hudson's Bay,

29 June 1926

Few ships of the same line contrasted fortune and fate and careers fulsome and fleeting as did Nascopie (1912-1947) and Bayrupert (1926-1927). Designed to compliment not replace the stalwart Nascopie, Bayrupert built on her design and was inspired by her success, indeed her gestation occurred amid a prosperous peacetime period for Hudson's Bay Co. whose unique barter system with the local Inuit and Indian communities of Canada showed new life after nearly 250 years of trading. Centered, of course, on Hudson Bay, HBC's network of trading posts extended right across Canada, but in the post-war era, it was the near Eastern Arctic that opened up new hunting grounds and the Labrador coast that promised new cooperation with other trading companies that spurred construction of new fleetmates for Nascopie to handle the increased obligation of supplying more and farther afield posts.

The Roaring Twenties of America and Canada were not nearly so prosperous for Britain with an enormous war debt to pay off, depressed world trade owing to high tariffs and intense labour strife, culminating in the General Strike of 1926. But if any British company thrived in the decade it was Hudson's Bay Co.. Their wartime contract with the French Government to act as their shipping and supply agents as well as to their allies Russia and Rumania had netted the company some $5.9 mn. over five years. But the real contribution to the coffers going into the post-war era was the positive mania among fashionable ladies for the beautiful fur of the white fox which inhabited the desolate hinterlands of Baffin Land. Such was the demand for white fox pelts that HBC reoriented their network of posts to Baffin Land during the first five years of the decade so that Nascopie's yearly voyage became longer and longer as the HBC network grew.

|

| Credit: The Beaver, May 1921. |

The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England, Trading into Hudson's Bay would begin the 1920s by celebrating their 250th anniversary (2 May 1670) of their royal charter from King Charles II with pageant, proclamations and profits. Celebrating the past was combined with expansion for the future and new posts were opened in Baffin Land including Pangnirtung (1921), Pond Inlet (1921), River Clyde (1923) and Arctic Bay (1926).

Hudson's Bay shareholders were among the most content of the era. The 1919-1920 (June to June) year recorded a net profit of £331,757 and paid a 40 per cent dividend on ordinary shares which was repeated in 1920-1921 despite a loss of £48,000. This was more than made up in 1921-1922 when a £550,448 profit paid a 45 per cent dividend. In 1922-1923, a profit of £348,441 was made, the fur trade alone earning £196,304 and in 1924-1925, HBC made £333,730.

All this fostered a renewal and expansion of HBC's ocean going fleet which carried "the outfit" (the trading goods and annual supplies) for the trading posts and "the returns," the immensely more valuable and much smaller, in tonnage, shipments of furs back to England. At the time, the HBC Steamer Department was led by Mr. James Thomson, who had managed the French fleet during the war, assisted by Capt. F. Walker, and their initial plans were based on the traditional economy of HBC management and the unique and exacting requirements of "trading North."

|

| Baychimo was the first new addition to the HBC trading fleet after the war. Credit: G.E. Mack photograph, McCord Stewart Museum. |

This began with the replacement of one of HBC most storied vessels, the 638-grt steam-assisted barque Pelican dating from 1877. In mid-1921, the Swedish-built Angermanaleven (1914/1,670 grt) which had been ceded to the British by her German owners as part of war reparations, was purchased for £15,000. Built for the Baltic, she had heavier plating and scantlings for navigation in light ice. The 230-ft. x 36-ft. ship was renamed Baychimo and made her first voyage north in July 1921.

|

| Bayeskimo of 1922 began a notable association between HBC and Ardrossan Dry Dock & Shipbuilding Co. Credit: Ardrossanherald.com |

Beginning a long association with the Scottish shipbuilders, Ardrossan Dry Dock & Shipbuilding Co., Ltd, the 1,391-grt, 212 ft. x 33.5 ft. Bayeskimo was launched there on 18 May 1922 and ran her trials on 24 June. She was reputedly bought on the stocks, but construction was apparently not so advanced to preclude substantially beefing up the framing forward, stem and shell plating as fitting of "a heavy stringer fitted through the whole length of the vessel with athwartships beams of pitch pine logs 12 x 12 inches, attached to it and spaced every six feet."

Bayeskimo had accommodation for 12 passengers and a 77,850 cu. ft. capacity (bale). Powered by a triple-expansion engine, and two boilers, she made 10.5 knots on trials. Marine Review and Marine Record, November 1922, stated "Of all the vessels owned and operated by the Hudson's Bay Co. in the 252 years of its fur trade, only one has been built directly for the company and especially constructed for its particular needs. That is the steamship Bayeskimo." This refutes or overlooks the possibility she was bought on the stocks, however. With her advent, Baychimo was transferred to HBC's Western Arctic operations based on Vancouver.

By this time Capt. F. Walker had succeeded James Thomson as head of the Steamer Department and James McLaren was engaged as HBC's Consultant Engineer and under the new leadership of HBC Governor Charles V. Sale and consultation with the Managing Director of the Ardrossan yard, Mr. E. Aitken-Quack, consideration of another newer and far larger ship began in May 1924 coinciding with the recent expansion into Baffinland.

Tenders for new ship were invited towards end of February 1925 when specifications finalised by Mr. McClaren. In the end, HBC seemed disposed to award the contract to Ardrossan Dry Dock & Shipbuilding given their satisfaction with Bayeskimo (as well as being the winter lay-up and annual overhaul yard for HBC) and only one other yard submitted a tender.

The Canadian Press, especially on the Pacific Coast, seemed to have "jumped the gun" with a flurry of reports of a newbuilding for HBC published at the end of 1924 and early into 1925, coupled with speculation that this might release Nascopie for the Vancouver-based service of the Company:

It is understood, a dispatch from London states, that a new and superb Arctic ship of great power will shortly be laid down to the order of the Hudson's Bay Company for immediate construction and she will be in commission for the 1926 season. Whether she will operate out of Western Canadian ports or replace the Baychimo on the Atlantic coast is as yet unknown. The question has been asked, but is still unaswered. It was expected, however, that she will be kept on the Atlantic, but the possibility exists she may be sent to western waters.

Since the Hudson's Bay Company lost their schooner Lady Kindersley they have been planning a change in their fleet of vessels operating in Canada's waters. The new ship will make a valuable and useful addition to this fleet, and satisfies all the wants and desires of the company for the northern operations.

Victoria Daily Times, 17 December 1924

A new ice vessel, 1,000 tons larger than the Nascopie, is to be laid down at once in British yards and will be ready for the 1926 season.

The Province, 7 January 1925

SHIPBUILDING CONTRACT FOR ARDROSSAN. The Hudson's Bay Company, London, have placed an order with the Ardrosaan Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Co. for a single-screw passenger and cargo steamer for ice navigation. The vessel will be 320 ft. in length between perpendiculars, 51 ft. in. moulded breadth, 31ft. 3in. in moulded depth, and of 3,500 tons deadweight on a mean draft of aft. The propelling machinery, which will be supplied by Messrs. John G. Kincaid Co., Greenock, will give a speed of 14 knots.

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 27 June 1925

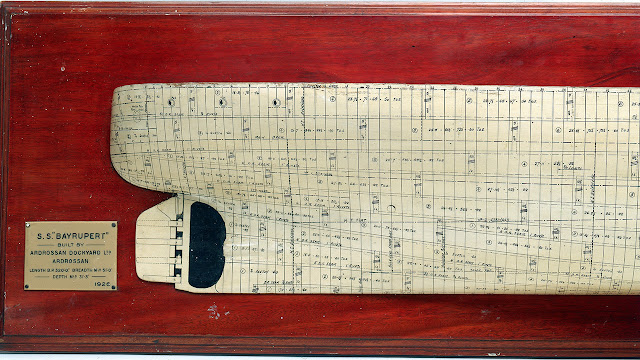

Yard no. 336 was laid down on 1 July 1925 at Ardrossan's South Yard.

If the future Bayrupert would go on to establish herself in the lamentable pantheon of ill-starred ships, her lack of fortune was shared by HBC ships during the mid 1920s. Indeed, she proved to be the infamous "third" in a trio of mishaps to Company ships on both ends of the continent. In 1924, the HBC motor assisted schooner Lady Kindersley (1904) sank off Herschel Island, Point Barrow, Alaska, after being nipped in the ice and crushed, loaded with machinery and stores and written off as a $420,000 loss. The following year the almost new Bayeskimo suffered a similar fate when she, too, was nipped in a heavy pack en route from Port Burwell to Fort Chimo and sank on 25 July 1925. All her people were put off in boats and spent a night on an ice floe before Nascopie arrived to rescue them.

Suddenly, construction of the ship seemed even more justifiable and her completion in time for the 1926 voyage North assumed even greater urgency.

On 29 September 1925 the Times Colonist reported that Hudson's Bay Co. had ordered the new ship "a single screw steamship for ice navigation,"from Adrossan Drydock & Shipbuilding Co. A complete specification was released at the same time calling for a length (b.p.) of 320 ft., beam of 41 ft. and a mean draught of 21 ft. with two complete decks, top gallant forecastle and cruiser stern. "The hull will be specially strengthened to resist ice pressure, and the equipment throughout will be a most comprehensive and up-to-date one." The propulsion machinery would consist of one triple-expansion engine driving a single screw and three forced-draught boilers. "The features of the company's s.s. Nascopie will be embodied in the new ship, with such improvements as experience has suggested. She will be named Bayrupert."

A powerful ice-breaking steamer, to be named the Bayrupert, and to carry 3500 tons deadweight, is now in the course of construction at Ardrossan, and the builders hope to complete here in time for the July voyage to the Hudson's Bay.

Statement at HBC General Court, 15 January 1926

The launch of Bayrupert is the stuff of legend, establishing at once the ship's unlucky reputation.

As she stood ready for launching on March 16, 1926, only a slide down the greased ways between here and the element for which she was built, she looked hesitant.

Perhaps that hesitancy was an omen, because it took four attempts to launch Bayrupert. On the first occasion, she refused all efforts to move her, including the best that power [sic] tugboats could provide. Two weeks later, on another high tide, she moved a mere 40 feet toward the sea before she stopped. A third attempt at launching the reluctant ship proved equally unsucessful. On the fourth try, Bayrupert pitched heavily from bow to stern and smacked her keel hard on rocks, damaging the bottom plates.

The Fur-Trade Fleet: Shipwrecks of the Hudson's Bay Company

Writing in the Times Colonist of 18 August 1985, Nancy Y. Middleton, the daughter of Capt. T.F. Smellie, provides the best account of Bayrupert's ill-fated launching (and she would later join her parents aboard the ship on her return from her maiden voyage, from Cardiff to Ardrossan):

The previous March [1926], Gov. Sale and a group of distinguished visitors came from London to Ardrossan for the launching. It was a gala day for the small town. A launching platform with red, white and blue bunting had been erected and a band played for the occasion.

The governor said, 'I name thee Bayrupert, May all who sail in thee have prosperity and good fortune.' The bottle of champagne broke and splashed against her boy. The ship did not move.

The second launching was scheduled for the next high tide, two weeks later, but without company officials, who had returned to London. The unwilling vessel slid 12 metres on the freshly greased ways and stopped.

The third attempt was even less successful; one again, she did not move.

On the fourth attempt, the Bayrupert slid off the ways into the water without ceremony. As the Captain was the most punctual of men, the launching must have run ahead of schedule. The reluctant ship crashed down on the rocks and damaged her bottom plating.

The worst of all seamen's omen had attended the launching: 'Unlucky the ship that refuses to leaves the ways.'

Yet, curiously, there was no mention of these extraordinary efforts to launch Bayrupert in the press or trade publications, nor any press accounts of christening plans for the vessel. Indeed, the one press account of the launch, in the Liverpool Journal of Commerce of 25 March 1926 merely states she was "launched on the 16th March" with no allowance for later and ultimately successful efforts to launch the vessel. Interestingly, a similar incident surrounded the launching of Deido at Adrossan in freezing weather in January 1928 and took three attempts over three days to send her down the ways.

The launch of Bayrupert would be the last of the old Ardrossan Dry Dock & Shipping Co. Ltd, for on 10 March 1926 it been announced that a new company, Ardrossan Dockyard Ltd. had been formed, with a capital of £100,000 to acquire the former company, yard and works.

Curiously, the Montreal Gazette seemed rather behind the information curve concerning the new ship and on 26 March 1926 reported that she would be named Bayrupert, according to information obtained yesterday," but "no further particulars concerning the Bayrupert are known here." It was made known however, "that she will be arrive in Montreal towards the end of June, in order to take on stores both for her own crew and the trading posts, sailing on or about the 7th of July, this being the date on which the Bayeskimo cleared from Montreal last year."

There was no doubting Bayrupert had been seriously damaged on the fourth and successful effort to launch her, bouncing at she hit the water and striking her underwater hull on the rocky bottom of the basin. On 3 April 1926 she was reported to be at Greenock and subsequently docked at Barclay, Curle's Elderslie yards, Glasgow, graving dock. There, surveyors noted: "keel plate and keel doublings, outboard strake port, and doubling, floors, intercostals, margin plate ports, and centre girder buckled or fractured between frames 153 and 165 inclusive." All of this was repaired and she was later shifted to berth 3, Victoria Harbour. On the 19th, Bayrupert was back at Ardrossan to complete her fitting out. It was back to Elderslie on 10 May for a second drydocking for cleaning and painting before trials.

|

| Bayrupert on trials. Credit: The Shipbuilder, June 1926. |

Bayrupert ran trials in the Firth of Clyde on 12 May 1926, recording a speed of 14.5 knots on her six-hour endurance run. She sailed from Ardrossan on the 27th for Tilbury where she arrived on 30th. She had survived the dramas of her launching and bested the worst the fates had for her, or so it was hoped. And Hudson's Bay Co., her builders, officers and crew could be rightly proud of a mighty fine vessel, the finest ever built for the line or purpose.

Whilst asking you to join with me in expressing our wishes for the success of the steamship Bayrupert, I desire to express the thanks of the Company to Mr. John McLaren, who has not only designed the vessel, but has given an infinite amount of time to the details of construction and equipment. I know that it has been largely a labour of love, but none the less we appreciate the devotion and skill which he has applied in such full measure.

I also wish to congratulate the Ardrossan Dockyards Limited, represented today by Mr. Fletcher, upon the excellent manner in which the contract has been carried out and upon the delivery of the vessel within contract time despite the difficulties with which they have had to contend.

HBC Governor Charles V. Sale

aboard H.B.S.S. Bayrupert, Tilbury

3 June 1926

|

| Bayrupert on trials looking so utterly marvelous that it alone was the inspiration for this monograph on her. Credit: William T. Tilley Collection. |

Bayrupert was designed by Mr. John McLaren, MINA, consulting engineer engaged by Hudson's Bay Co. If Nascopie was an exemplar of Edwardian naval architecture with her light lines, minimal superstructure and towering slender funnel, Bayrupert was the archtypical British 'twenties liner, a half-sized version of one of the British India "M" class on first glance: robust and businesslike. Compared to Nascopie, her 3,500 deadweight tons were carried in a hull of far greater freeboard and she was a dryer ship and a steadier one for it. To allow a long foredeck to accommodate the substantial deck cargoes carried north, the machinery and boiler spaces were sited quite a bit aft of amidships so Bayrupert's profile was decidely off balance but not displeasingly so.

|

| Credit: The Gazette, 9 June 1926. |

Measuring 335 ft. 6 ins. (length, overall), 320 ft. 6 ins. (length, b.p.) and 51 ft. 6 ins. (beam), 21' 9¾" (loaded draught), the 4,037-gross ton (2,414 tons nett) Bayrupert was notable for being the first (and only) passenger-cargo steamship wholly designed and built on account of the Hudson's Bay Co., recalling that Nascopie had been a joint project with Job Bros., and the largest and finest passenger ship built for the Arctic region. She was also the last British-built icebreaking merchantman, ending a unique class of ship started back in 1906 with Adventure.

'The ship was built to Lloyd's special survey, including the notation 'Strengthened for Navigation in Ice,' but, in point of fact, the shell plating, framing and side stringers are much in excess of the strength required by Lloyd's.' (Gazette, 9 June 1926).

It will be remembered that the Bayeskimo, which the Bayrupert is replacing, was crushed in the ice of Ungava Bay, on Hudson Strait, last summer. The Hudson's Bay Company have, as a result, made their new boat particularly strong to withstand the rigors of the route that has to take in making her annual round of the northern posts with stores.

The Gazette, 9 June 1926

The loss of Bayeskimo the previous year testified to the tremendous power of ice pressure on even a reinforced steel hull and Bayrupert's construction exceeded even that of Nascopie in strength, but course her specifications and design were already finalised well before Bayeskimo sank.

Whereas it had been the practice, during sealing voyages, to reinforce Nascopie's forepeak with one-foot square wooden "ice beams," in the new ship this feature was made permanent in the form of the stringers being carried solid across the forepeak, to resist ice pressure, while more traditional pitch pine beams were fitted in three tiers in no. 1 hold, and in two tiers in no. 2 and 3 holds in same vertical plane as the side stringers.

Like Nascopie, the rest of ship was literally built like battleship. From the bow to the after end of no. 1 hold the shell plating was doubled, achieving flush plating from above the load water line to the keel with the double thickness tapering from 1.76 in. at the bow to 1.4 in. at the after end of the hold. An ice belt was fitted from aft of no. 1 hold to the stern, extending about a foot above the load water line to about 4 ft. below it, the plating being single and .92 in. thick.

|

| Stern detail of builder's model showing the huge, reinforced rudder. Credit: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. |

The stem, like Nascopie, was of sold cast steel, very heavy in section and the bow featured the pronounced curve up from the keel for icebreaking,. The stern, of the modern full cruiser shape, was specially curved for ice and of cast steel, very heavy in section, and rabbeted to take in the ends of the shell plating. The rudder was specially large and suitable for working in heavy ice.

Bayrupert's hull was divided by five watertight bulkheads extending to the superstructure deck.

|

| Midships section. Credit: Lloyd's Register Foundation. |

Like Nascopie, Bayrupert had three holds, no. 1 (21 ft. 3 in. x 16 ft. hatch) and no. 2 (31 ft. 3 ins. x 16 ft. ft. hatch) forward and no. 3 ( 36 ft. 9 ins. x 16 ft. hatch) aft). Unlike her elder fleetmate, she had insulated chambers, with a 16-ton capacity and refrigerating machinery. Cargo handling gear comprised six steam winches working two 5-ton derricks at no. 1 hatch, two 5-ton and one 25-ton derrick at no. 2 hatch and two 5-ton and one 10-ton derrick at no. 3 hatch. Unique to her intended duty, on Main Deck aft was a "dust-proof" and "rat proof" compartment bounded by steel bulkheads for the stowage of her valuable bales of fur.

A steam windlass of extra heavy type was fitted on the forecastle head and provision for a heavy stream anchor through a hawse pipe in the stern.

|

| Bayrupert's machinery was constructed the well-known Greenock firm of John G. Kincaid. |

Designed for the exacting requirements of icebreaking with its constant revolution changes and alternating forward and aft propulsion, Bayrupert was, like Nascopie, powered by a single triple-expansion engine (built by Messrs. John G. Kincaid & Co. Ltd, Greenock) with cylinders 23½, 37½ and 63 in. diameter with a 39 in. stroke, and supplied by three single-ended boilers, 15 ft. 9 in. dia. and 11 ft. 6 in. long, working at 200 psi under the Howden's system of forced draught. Because of the ease of carrying it, Bayrupert was a coal burner although her deep tanks were sealed to, if needed at a future date, hold oil fuel. At an average speed of 10 knots, she burned 28 tons of Welsh coal per day. Like everything else, the specification for the screw shaft was well in excess of Lloyd standards being 13⅝" in diameter.

|

| "A Range-Finder for Sailing in Uncharted Seas.' Credit: The Sphere, 12 June 1926. |

The new ship was elaborately equipped with the "latest scientific aids to navigation," including a Sperry gyro compass outfit and helm indicator gear, a Barr and Stroud Mark F.Q. range finder, "somewhat similar to that used in the artillery," an 'Echo' type underwater sounding machine, a "Sal" type underwater log, and a Marconi wireless direction finding apparatus.

Bayrupert's lifesaving equipment comprised two 50-man lifeboats and two 27-man motorboats carried at Welin quadrant davits on the Boat Deck of the main superstructure and two 12-man cutters at radial davits atop the poop deckhouse.

|

| Deck plan and profile of Bayrupert. Credit: Lloyd's Register Foundation. |

H.B.S.S. BAYRUPERT

Profile & Deck Plan

Credit: The Shipbuilder & Marine Engine Builder, June 1926

LEFT CLICK on image for full scan.

|

| Profile and Rigging Plan. |

|

| Navigation Bridge & Compass Platform |

|

| Boat Deck |

|

| Boat Deck Aft |

|

| Forecastle Deck |

|

| Promenade Deck |

|

| Shelter Deck |

|

| Shelter Deck detail of accommodation. |

|

| Main Deck |

The Bayrupert is the first ship in the service of the Hudson's Bay Company to be fitted for carrying passengers, and there are accommodations for 72 persons. While it is not the intention of the Company to carry passengers in the usual way, Government officials, scientific expeditions and others whose business may carry them to Hudson Bay will be carried by special arrangement.

Sperryscope, 1926

Bayrupert had three superstructure decks. Boat Deck had the captain's cabin and day room forward in a separate house with the bridge and compass platform above, two pairs of boats in Welin quadrant davits, a coal hatch and trunk cargo hatch forward of the funnel and another coal hatch aft of it, open deck space and right aft in its own house, the wireless room with accommodation for the two operators.

The Promenade Deck had the principal accommodation and small smoke room aft and, in a welcome advance over Nascopie, ample covered promenade deck surrounding. The Shelter Deck amidships had engineers and officers accommodation and the dining saloon with a raised forecastle forward with crew accommodation and a poop house with petty officer accommodation and hospital.

Main Deck was the one full length hull deck with 'tween decks, accommodation for 56 Inuit passengers, special fur room and steward and petty officer accommodation aft.

Unlike Nascopie, which did not initially possess a passenger certificate, Bayrupert had a full certificate and accommodation for 72 passengers in well-fitted, outside two-bedded cabins (15 on Promenade Deck) and two on Shelter Deck with hot and cold running water, fitted wardrobes and steam-heating and two rather remarkably spacious suites forward on Promenade Deck with separate living room and bedroom and private bath and "tastefully panelled in mahogany and upholstered in tapestry." These were intended for the Governor and other VIP passengers. "Commodious lavatory accommodation is provided, the fittings being of excellent quality," for occupant of the rest of the cabins."

The dining saloon, forward on Shelter Deck, with large portholes facing forward and to the side, with seats for 36 in fixed seats upholstered in natural coloured leather and smaller tables, was panelled in oak. There was also a smoking room, albeit of very small proportions, aft on Promenade Deck, with two seating alcoves, and panelled in waxed oak, and fitted with bookcases. There was a spacious entrance foyer and main stairway for on Promenade Deck with skylight overhead and panelled in mahogany.

It was stated at her introduction that Bayrupert's accommodation was of sufficient quality to enable the vessel to be used for cruise charters, although her lack of public rooms save for the dining saloon and tiny smoke room had to be taken into consideration and, of course, in the event, she did not last long enough to prompt any off season employment.

An increasing aspect of HBC's passenger trade was the carriage of small groups of Inuit families (and their dogs) from one post to another as the Company opened new settlements and closed others as trade and hunting patterns dictated. For this, the new ship had 'tween deck accommodation for 56 Eskimos in the no. 1 'tween deck forward on Main deck with open deck space above and toilets and washing facilities in the forecastle.

Accommodation for both officers and crew (62 in all) was a considerable advance on Nascopie's, reflective of the long, arduous route. The ship featured a spacious office for the purser and HBC clerical staff and petty officers had two-berth cabins while seamen and firemen had separate quarters and messrooms forward. Stewards and petty officers were housed aft.

Irrespective of her ultimate fortune and fate, Bayrupert was an outstanding vessel both in the history of Hudson's Bay Co. and of the classic interwar era of the British merchantman. That so handsome and well-found vessel, designed and built to withstand the perils of ice would be claimed, instead, by rock, proves the Fate came be as cruel as she is capricious. But first, a brief heyday for ship, service and the Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay.

.jpg) |

| Credit: Edmonton Journal, 3 July 1926. |

On the 3rd of June, 1926, the 258th anniversary of the first sailing of the ketch Nonsuch from Gravesend in the fur trade service of the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay, the S.S. Bayrupert left Tilbury Docks, London, England, on the Thames immediately opposite Gravesend, and the event was the occasion of the repetition of an interesting old-time ceremony, when Governor C. V. Sale, Mr. F. H. Richmond, Deputy Governor, and Messrs. V. H: Smith, L. D. Cunliffe and Sir Hewitt Skinner, members of the Committee went aboard to wish the captain and his crew a safe and prosperous voyage and to hand over to Captain T.F. Smellie the papers and dispatches for the Company's posts. These documents were contained in the Companv’s oak dispatch box known as the "Gravesend Box," which had done service in this capacity for many generations.

The Beaver, September 1926

1926

|

| Credit: Daily Colonist, 1 May 1927 |

Having wisely overlooked her frustrated launchings, HBC's publicity department did themselves proud with Bayrupert's triumphant and historically symbolic departure from London (Tilbury) on 3 June 1926 which happened to be the 258th anniversary of the sailing of the ketch Nonsuch from Gravesend for Hudson Bay in 1668. The new ship was also the setting for the annual meeting of the Governor, Charles V. Sale, and Committee prior to her departure.

|

| Governor Sale consigns HBC's ancient "Gravesend Box" containing official correspondence for the northern post over to Capt. Smellie. Credit: The Beaver. |

It was the perfect melding of past, present and future and there were few companies, even English ones, which could boast of 258 years of enterprise let alone conducting the same voyage for every one of them. If the 50-ton Nonsuch and the 4,000-ton Bayrupert represented an astonishing contrast in maritime architecture and engineering, their trade was just as remarkably unchanged. The Company of Adventurers Trading into Hudson's Bay never made a "thing" about their vessels, be it a canoe or Peterhead whaler or the world's finest icebreaking combination cargo-passenger liner... it was the outfit and the return that they carried under the HBC houseflag to and from the farthest northern reaches of The British Empire that mattered to shareholders or to the Inuit trapper watching for first glimpse of funnel smoke on Ship Day.

The staff of HBC's London office were treated to a half day holiday and on Derby Day, voyaged down the Thames in a launch chartered for the occasion to see the new ship, "a very interesting and pleasant trip was spoilt only by the rain, which persisted from start to finish."

|

| Photos taken aboard Bayrupert before her sailing from Tilbury showing the Boat Deck, radio direction finder antenna and some of her crew members. Credit: The Beaver. |

|

| Capt. T.F. Smellie (left) and Chief Engineer J. Ledingham aboard Bayrupert. Credit: McCord Stewart Museum. |

Like any new flagship, Bayrupert got the pick of Nascopie's senior officers and staff, including Captain T.F. Smellie, Chief Engineer Ledingham and Chief Steward Reid as Governor Sales noted in the conclusion of his speech aboard that day:

I am very pleased that the placing of this vessel in commission has enabled us to appoint Captain Smellie in command and Mr. Ledingham as chief engineer. They have already made many voyages to the Bay in the Company's servive and in honouring the toast 'Success to the Bayrupert,' I ask you to join with me in wishing them a pleasant and prosperous voyage.'

|

| Bayrupert departs Tilbury on her delivery voyage, 3 June 1926. Credit: Syren & Shipping, 9 June 1926. |

|

| With P&O's Rajputana and Comorin in the background, Bayrupert sails from Tilbury. Credit: The Beaver. |

Departing Tilbury on 3 June 1926, Bayrupert occupied 16 days on her delivery/maiden voyage, pausing at Quebec on the 18th and arriving at Montreal on the afternoon of the 19th after a two-day call (15-16) at Sydney, NS, to take on coal. When she docked at Shed 47, Tarte Pier, foot of Nicolet Street, the shed was packed to the rafters that season's "oufit" (no. 255) for the North which she and Nascopie would be carrying including 19 boats of every description and 12 canoes. Among her varied cargo, Bayrupert would also "carry ten large charges of thermite prepared by Professor Howard T. Barnes, of McGill University, for use in the event of the ice pressure at any time becoming too great, and requiring to be relieved."

|

| Bayrupert alongside Montreal's Shed 47 prior to sailing on her maiden voyage. Credit: Sydney R. Montague photograph, www.isuma.tv/ |

Leaving the Baffin Land and far north ports to Nascopie, Bayrupert's maiden voyage would take her to northern Quebec, the Labrador Coast, Hudson and James Bays, call at Cartwright, Port Burwell, Wolstenholme, Chesterfield, Churchill, Charlton, Southampton Island, Port Harrison, Wolstenholme, Lake Harbour, Port Burwell and finally St. John's where, after bunkering, she would cross the Atlantic to Ardrossan.

Bayrupert had 29 passengers aboard for her first trip, all HBC personnel except for three clergymen and three RCMP men. She also sailed with 30 pigs, nine being for the ship's galley and, 21 for the northern posts. The latter came from a different farm and sadly died from swine flu early into the voyage.

Canada added a new page to her history when the S.S. Bayrupert, of the Hudson's Bay Company, cast off from Tarte pier in the shimmering heat of yesterday afternoon.

The departure was more than just another ship putting to sea. It was the maiden voyage of a vessel flying the houseflag of a company whose record is part of the story of the development of the Canadian northland. The Bayrupert carries men and materials to help the new nation Canada is making in the Arctic. From ports in Hudson's Bay she will bring back furs to be exchanged for more negotiable wealth in the great markets of London.

Scarlet tunic and black soutanc were in vivid contrast on the promenade deck. They were worn by young men upholding the tradition of the other young men of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and Oblate Fathers, who for many years have kept the peacce and spread enlightenment in the Dominion's outposts.

The 'Mounties' include Staff-Sergeant Joyce, an old hand in the ways of the north, and Constables S.R. Montage and H. McMahon, men barely out of their teens. Staff Sergeant Joyce, who is accompanied by his wife and two children, will go to Chesterfield Inlet with Constable McMahon.

Constable Montague, a thin-lipped, blond youth from Edmonton, is detailed to the post at Port Burwell in Hudson's Straits. He will replace another 'Mountie" as the sole representative of the law at that point.

Before the ship sailed a friend said to Montague: 'Pretty hard lines, old man, being shoved into that frigid country instead of enjoying the balmy breezes of the Pacific Coast.' Montague replied simply; 'I'd rather go north than feel those balmy breezes. It makes me feel like a real member of the RCMP.'

Father Marcel Rio and Father Thibert, youthful members of the Oblate Order, come from sun-strewn France to bring the spiritual meaning of life a little nearer to a few Eskimos.

'How long will you be there?' Father Rio was asked.

'About as long as the Bon Dieu lets us,' he smiled. 'It will be very interesting. I have first to master the English language. Then, as the mission has been opened only recently, there is a tremendous amount of work to be done.'

The remainder of the twenty-nine passengers include Hudson's Bay Company employees and churchmen. The ship is commanded by Captain T. Smellie, who has been with the company for more than a decade. His last command was the Nascopie.

The Gazette, 16 July 1926

|

| Taken on deck as Bayrupert sails from Montreal on her maiden voyage. Credit: Sydney R. Montague photograph, www.isuma.tv |

One of the RCMP aboard was Constable Sydney R. Montague, who would, with Cpl. Henry George Nichols, establish the new police station at Port Burwell, Hudson Strait, and later write a popular account of his experiences North to Adventure in 1939. Sgt. Montague also extensively photographed the sailing and they provide a unique a record of Bayrupert's maiden voyage.

Photographs taken of Bayrupert on her maiden voyage

|

| Anchored in Erik Cove, Wolstenholme. Credit: Frederick W. Bercham photograph, McCord Stewart Museum. |

.jpg) |

| Another unidentified location, possibly Hebron on the Labrador coast. Credit: Joseph Dewey Soper photograph, Canadian Museum of History |

|

| Capt. Smellie and RCMP Constable Sydney R. Montague and others aboard Bayrupert. Credit: Sydney R. Montague, www.isuma.tv |

|

| Lifeboat drill. Credit: Sydney R. Montague, www.isuma.tv |

|

| A very lightly loaded Bayrupert at Mukkovik, Labrador in September 1926. Credit: Libraries and Archives Canada. |

|

| At Chesterfield. Credit: The Beaver. |

ARCTIC TALKS. The first recorded transmission of the human voice from one merchant ship to another over the Arctic Circle is reported the Hudson Brie Co. as having taken place during the last voyage of the s.s. Bayrupert. This ship was fitted with a 100-watt Marconi wireless 'phone, set at Montreal before starting on her voyage to the trading posts in the Hudson Bay at the beginning of the summer. Very much greater ranges than had been anticipated were achieved, and on 30 August speech from the Bayrupert was clearly received on the Daymaud and the Baychimo, which were 600 miles and 1,100 miles distant, respectively, over the Arctic Circle.

Birmingham Daily Gazette, 14 January 1927

Bayrupert's maiden voyage was remarkable for its almost complete lack of incident, excitement or even bad weather. Indeed, very little ice was even enountered (except near Port Nelson on the way back) to test the ship's capabilities and construction. The annual "outfit" voyage was seldom a "milk run," but this certainly was.

The main newsworthy element of the voyage, in a radio and wireless mad world, was the miracle of long distance communication to the far reaches of the Arctic. Prior to sailing from Montreal, Bayrupert's already state of the art radio shack was equipped with the latest 100-watt Marconi radio telephone set. This would enable, for the first time, direct communication with posts 24 hours prior to arrival. And far more distant communication was demonstated on the voyage. Wireless operator D. Mitchell of Baychimo, in the Western Arctic, reported he was in radio telephone communication for two nights with Bayrupert, 1,200 miles distant, in the northern reaches of Hudson Bay. Baychimo's Purser Patmore said he had "a sustained conversation with one of the Hudson's Bay Company's district managers, who was on board SS Bayrupert." On 30 August Bayrupert was again in radio telephone communication with Daymaud and Baychimo, 1,100 miles away.

Bayrupert called at Cartright on 23 July 1926, Charleton Island on 19 August and homeward, Port Burwell on 14 September, sailing from there on the 16th. Making a fast three-day run from Cartwright, she arrived at St. John's on 30 September "with a cargo of salmon and furs," and departed there on 4 October for Montreal.

On the morning of 9 October 1926, Bayrupert arrived at Montreal.

Captain T. Smellie, who is commanding the Bayrupert on this her maiden voyage, declared that his ship had surpassed expectations and that she proved herself thoroughly satisfactory in the trade for which she was constructed. Similar opinions were expressed by others making the trip through Hudson Strait into the bay of the same name. The trip was described as being the least momentous of any that Captain Smellie has made to the northern latitudes since he took the Nascopie up in 1917. This he attributed to the fine sailing qualifications of his ship, for she responded to his every wish.

Ice conditions in the Bay were said to be more favorable this year for the passage of steamers through Hudson Strait, though a large quantity of ice was seen in the vicinity of Port Nelson. Captain Smellie was of opinion that the Bayrupert could have forced her way through this barrier to the port, but was doubtless if any ship not constructed for navigation through ice would have been able to accomplish the task. It was in August that the field ice surrounding Port Nelson was observed by the skipper and his crew.

During the sojourn of the Bayrupert in Hudson Bay, she met the S.S. Nascopie, which left Montreal on July 10, five days previous to the Bayrupert's departure. This vessel proceeded further north to Pond's Inlet and is now bound for St. John's, Nfld., and Sydney, N.S., where she will coal for the return trip and Scotland.

There is a possibility of the Bayrupert being placed in a passenger service during the period when is not employed in making trips to the North or in refitting, as she has accommodation for 72 passenger in well-appointment staterooms, and for which fine public rooms have been installed. Nothing definite has yet been arranged, as there may be better opportunities for the carriage of cargo across the Atlantic during the winter months, if the British coal strike is still in progress when her overhaul has been effected.

The Gazette, 11 October 1926

With 108,000 bushels of wheat, her valuable cargo of furs, "packages of feathers, guns for repair, books, ivory, 10 cases of castorium, mineral samples and curios," Bayrupert sailed from Montreal on 14 October 1926 for Sydney, NS, to "take on bunkers for the trip across the Atlantic, and possibly sufficient for her return trip to this continent." The morning of her departure, she was inspected by HBC Governor Charles V. Sale, who was on an inspection trip to Canada. It had been reported in the British press that he and Mrs. Sale might return to England aboard Bayrupert, but they remained in Canada for some time later in the year.

After coaling at Sydney on 19 October 1926, Bayrupert arrived at Bute East Dock, Cardiff, on the 30th. She landed a consignment of furs worth £200,000 and that year's fur collection was 10 per cent greater but "the realised prices were, however, lower than at any time during the last six years and averaged about 60 per cent. Less than obtained in 1920." (HBC annual report, June 1926). Bayrupert arrived at Ardrossan on 10 November and laid up there for the winter.

1927

|

| Bayrupert at Hebron in 1926, one of the Moravian Mission stations that HBC would now serve. Credit: The Beaver, June 1927. |

Hudson's Bay Co.'s main rivals in trading in the bay and Labrador were the Moravian Mission and the French firm Revillon Freres, at one time the largest fur company in the world. But with the advent of Bayrupert and teamed with Nascopie, the two could more efficiently serve their posts in addition to HBC's and this would come into effect with the 1927 season with HBC obtaining a 21-year lease on five Moravian Mission settlements on the Labrador coast: Nain, Okak, Hopedale, Hebron and Makkovik. The venerable Harmony which for the last 26 years had supplied these posts from London, was retired and they were added to the HBC network and to the duties of Bayrupert and Nascopie. Most of these were called at prior to arrival at Port Burwell. After a wonderful and varied 51-year-career that began as one of the famous "Tea Clippers," Lorna Doon, Harmony sailed from Dartmouth on 5 August 1926 on her last voyage and broken up the following year.

With the HBC steamers now supplying the Revillon Freres posts as well, that company's motor schooners Albert Revillon and Jean Revillon were sold to HBC and, fitted with cold storage, put on the salmon trade along the Newfoundland-Labrador coasts.

Although Bayrupert had successfully test called at Hebron (by far the best natural harbour in Labrador) and Mikkevic, Labrador, on her maiden voyage in 1926, "her captain reported to the officials in London that he did not consider it advisable for her to call at the posts along the rocky Labrador coast, which could be visited by smaller vessels. His warning was unheeded." (Nancy Y. Middleton, Times Colonist, 18 August 1985.) Of special concern to Capt. Smellie was Bayrupert's fully loaded draught (as she would be as Labrador calls would be made early in the voyage) of 24 ft. which was about two feet greater than Nascopie's and far greater than the 463-grt Harmony which had so long served them.

Despite Smellie's concerns, it was precisely these Moravian Mission posts which would figure in the first half of Bayrupert's 1927 voyage, but possibly owing to his caution, among her passengers coming over from Scotland was Harmony's former master, Capt. J.C. Jackson, who would stay aboard for the voyage north in an advisory capacity during the initial calls at the Moravian posts. Another experienced hand from Harmony, was her former First Officer for 20 years, A.W. Bush, who assumed the same position aboard Bayrupert. The ships' officers included Mr. Ritchie as Purser and again J. Ledingham as the Chief Engineer.

Ending her seven-month-long hibernation, Bayrupert was drydocked at Barclay, Curle & Co.'s Elderslie yard on 20 May 1927 for "cleaning, painting and some slight repairs," and was undocked on the 23rd, sailing back to Ardrossan on the 27th. Bayrupert sailed for Montreal on 16 June.

We left Ardrossan on June 16th, 1927-- 29 of us all told-- on the Hudson's Bay Company's new icebreaker, S.S. Bayrupert, of some 4,000 tons, and, after a fairly stormy voyage across the 'Western,' we nosed our way through fog and icebergs into the glorious heat and sunshine of the St. Lawrence.

Life in the Hudson's Bay Company

Strathallan School Magazine, 1933

Bayrupert arrived at Montreal at 4:30 p.m. on 28 June 1927, docking at HBC's Shed 47. She came down via the Belle Isle Strait and did the passage from Ardrossan in 12 days.

In addition to her crew, the Bayrupert brought out 29 boys between the ages of 18 and 21 who will be engaged as apprentice clerks in the company's northern posts or in the West. Nine of these young men are going north with Bayrupert, while the balance will proceed to Winnipeg, where they will be placed in one of the Hudson's Bay Company stores. Most of the young men came from Scotland, all parts being represented, and others are from England. All are fine looking young chaps and should make fine additions to Canada's populaton.

The Gazette, 29 June 1927

It promised to be a busy summer indeed for Bayrupert, sailing on 11 July, and Nascopie the following day, each on different routes. Bayrupert would serve the new Moravian posts, starting with Rigolet on the Hamilton River, then north along the Labrador coast to Hopedale, Nain, Okkak and Hebron before calling at Port Burwell and then the HBC posts at Stupart's Bay, Churchill and Charlton Island, and after a second call at Port Burwell, sailing direct for Ardossan. Nascopie would, after Port Burwell, serve Lake Harbour, Dorset, Chesterfield, Wolstenholme and then via the Davis Strait to Baffin Island.

Among Bayrupert's passengers were Rev. Father O'Brien, for Rigolet, and Dr. R.P. Stewart of Toronto, in addition to 25 HBC employees including S.H. Parsons, Labrador sub-district manager and Dr. R.B. Steward and Dr. R.B. Stewart.

We then set sail for Labrador, and were given a rousing send-off by the gaily dressed crowd who lined dock wall-- our Montreal staff, with relatives and friends of those embarking (some for the first time) to follow in the footsteps of the great company of adventurers who, for 258 years, have kept the Hudson's Bay Company flag flying, from Montreal northward, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and emulating the lead and deeds of men whose names will ever live in the history of Canada, men such as Strathcona, Simpson, Dr. Rae and others.

Life in the Hudson's Bay Company

Strathallan School Magazine, 1933

Her decks piled high with whaling boats and canoes, sacks of coal and live stock, the Hudson's Bay Company S.S. Bayrupert cast off her moorings at 5.30 o'clock yesterday afternoon and commenced her long voyage to Labrador, Hudson Strait and Hudson Bay. She left her berth at Shed 46 and sailed upstream to the calmer waters of the harbor before turning round with her valuable cargo and making for the opens sea.

The live stock created some little interest, four sheep in a pen on the poop being joined at the moment by three others taken aboard each in a different fashion. One walked onto the Bayrupert, one was carried right side up and the third was taken aboard wrong side up but without offering any protest.

There were eight pigs in a pen on the forward deck and a number of fowl in a hutch on the poop.

It was a joyful party that sailed away on the Bayrupert, many of the passengers being apprentice clerks between the ages of 18 and 21 who are going up to the Hudson's Bay posts in the north. They made many friends during their brief stay in Montreal and there were many people down to see them off.

The Gazette, 12 July 1927

|

| Dated 1927 and taken by her Second Officer, this may be the last photograph of Bayrupert before her grounding. Credit: John M. Kinnaird photograph, McCord Stewart Museum. |

In what seemed a repeat of the favourable conditions encountered the previous year, Bayrupert's voyage was enjoyed in fine weather and she called without incident and on schedule at Cartwright on 16 July 1927, Rigolet on the 18th, Makkovit (19) and Hopedale on the 21st.

Ten days later we arrived at Cartwright, the largest and most southerly post in Labrador. All hands set to discharging the varied cargo of provisions, rifles, ammunition, engines, in fact, 'everything from a needle to an anchor.'

This was our first taste of Hudson Bay Co.'s methods and work at a trading post, and I might add that the enthusiasm of some of the newcomers was slightly dampened by this rude awakening from the leisure of a month's voyage to a hard day's work discharging cargo, hampered by the presence of mosquitoes and black flies.

After working day and night, we steamed to Rigolet Post where the same work was gone through, and thence to Makkovik, the first Eskimo post. Here we first saw full blooded Eskimos, and a tough lot they looked. We left here early in the morning and proceeded to Davis Inlet…

Life in the Hudson's Bay Company

Strathallan School Magazine, 1933

Indicative of just how challenging and exacting navigation was along the Labrador coast are the following detailed notes Capt. Smellie had of the courses he used just from Makkovik to Hopedale on this voyage:

Makkovik to Hopedale. A route taken by Captain Smellie of the Bayrupert in 1927 is described as follows: After passing the narrows, make good a course of 26° for about 2½ miles and you will pass ½ mile off Anderson Point. Alter course to 11° and you will pass a rock awash ½ mile off on the starboard side 134 miles from Anderson Point. This course takes you clear of the North Sister, 34 miles from the rock awash, and passes ½ mile off the North Sister. This rock is not named on the chart, but both rocks lie northeastward of Cape Mokkovik.

Having rounded the North Sister make good a course of 272° for the southern end of West Turnavik, passing about 1,400 yards off Cape Aillik. Having steered 34 miles from Cape Aillik you pass and round to the southward of the first large island at a distance of about 520 yards. Several reefs and rocks lie northward and southward of the route. Make good a course of 307° to pass about 470 yards off the northeastern end of West Turnavik. The house in the center of West Turnavik and Cape Mokkovik in line, bearing 276°, leads clear of all dangers.

Having rounded West Turnavik at about 470 yards make good a course of 281° for Striped Island. The northern end of West Turnavik in line with the southern end of Striped Island, bearing 285°, leads clear of all dangers. The Lily. Islands group are passed to the northward at a distance of about 1,300 yards; several rocks, awash, are passed on the northern side of the route. When Striped Island is abeam, distant about 480 yards, make good a course of 285°; the beacon on White Island, consisting of a staff and ball, bears 298° distant about 1910 miles.

"The houses on Tikkerasuk Island bearing 285° lead clear of White Island with the beacon on it, which is passed ½ mile off. Alter course when this beacon is abeam to 355°, passing about 850 yards off the light-tower on the northern point of Tikkerasuk (55°20′ N., 59°43′ W.. B. A. Chart 375).

"When the light-tower is abeam, about 850 yards, make good a course of 285°, and a black conical hill will appear ahead. A beacon, with oblong topmark to the right of the hill, in line with the point. on which the light-tower stands, bearing 290°, leads clear of all dangers. When approaching this beacon, or the narrows, making good a course of 285°, you pass a rock, 15 feet high, 960 yards off on the starboard hand. At the same time you pass on the port hand a larger islet. Bring the point with oblong beacon bearing 2 degrees on the starboard bow, and a small rock 2 degrees on the port bow,passing midway between them. A small rock, which dries about 3 feet, bears 298° distant 110 miles from flagstaff at Narrows Point. The same rock also bears 298° in line with a point with a stone beacon on it, named Iron Island Point. Having passed this rock 400 yards off, bring the stone beacon on Iron Island Point ahead and the beacon on Flagstaff Island astern, which clears a shoal on the starboard side of the run. Pass close to Iron Island Point with the stone beacon on it, and a course of 283° will pass 650 yards off Anniowaktook; Hopedale will now be seen, and after passing Dogs Island, anchor with the small rock bearing 26° in 13 fathoms.

Sailing Directions for Northern Canada Including the Coast of Labrador North

By a peculiar coincidence the Hudson's Bay Company have been unfortunate in losing three of their steamers on approximately the same date in three different years.

As early as 1888 their S.S. Beaver, the pioneer steamship of the Pacific Ocean, which was built at Blackwall, England, in 1835 for the company, was wrecked on Prospect Point, Burrard Inlet, Vancouver, on July 23.

The S.S. Bayeskimo, predecessor to the Bayrupert, sank in Ungava Bay, off Hudson Strait on July 23, 1925, having been crushed in the ice; and now the Bayrupert appears to have ended her career on July 22 this year.

The Gazette, 29 July 1927

In the early hours of 22 July 1927, making course from Hopedale for Nain, Capt. Smellie took Bayrupert away from the shore and steamed her eastward for 15 miles to deeper water before changing course northward to Nain.

After departing Hopedale, the next stop was Nain and instead of navigating between various unnamed islands, the Captain decided to proceed eastward and then north until the Bayrupert would be in the latitude of Nain. The Captain was on the bridge when the last islands, named the Farmyard Islands, were passed. After steaming 15 miles to the east the ship's course was altered to the north. No land was in sight except astern. At seven a.m., after hours on the bridge, the Captain passed the ship over to the Chief Officer and retired below, confident that all danger was passed.

Arctic Command.

At 7:15 a.m. on 22 July 1927 Bayrupert struck a submerged rock, ten miles off the mainland, 14 miles north of Cape Harrigan, which everyone aboard first thought was an iceberg. This is sometimes referred to as Clinker Rock, which was first charted by Harmony, as lying at a depth of less than one fathom and 10 miles northeastward of Cape Harrigan light tower. So clearly not the same as previously charted. Sailing Directions for Northern Canada including The Coast of Labrador, 1947, cautions: "The following route from Hopedale to Windy Tickle, taken by Capt. T.F. Smellie of the Bayrupert, in 1927, should be used with caution, as several of the islets and dangers mentioned are not shown on the chart, and some of the name given have not been inserted thereon."

Ten minutes later, in a moderate swell, the ship cracked down on something submerged. As soon as the Captain was back on the bridge, he knew she was fast. The swell lifted her up slowly and dropped her down again with a sickening regularity. Deck fittings began to shake with the pounding, and every piece of crockery on board was smashed in the first few moments. No rocks were visible from the bridge. The depth of water was taken all round the ship, and under the bows were 120 feet of water, under the stern 150 feet. But directly in the centre of the ship, the soundings showed twenty-two feet. She was pierced by the top two feet of a pinnacle.

The Captain ordered the ships engines ahead and astern, and an inspection showed that the pinnacle was actually showing directly under the boilers. The swell only served to pinion her on the strange underseas mountain. The Captain knew she was probably doomed. She couldn't get the pinnacle.

Arctic Command

Bayrupert was essentially impaled amidships and the swell plus the tide only made her ground her keel and deep tanks deep into the piercing rock. Capt. Smellie ordered all the deck cargo, including her many boats and canoes, put over the side to lighten her but no amount of effort would rise her amidships the two or three feet to clear her off the rock.

I just got back in my bunk and was going to sleep a little longer till the gong went for breakfast, and all of a sudden there was a scraping bump that just about threw me out of bed. I was kind of jolted up and hit my head against the bunk above me.

I looked out of the porthole, and I could see heads sticking out all along the side where the cabins were. They were all looking to see what was going on. Some people were still in their nightclothes, and some men had one side of their face shaved, and one side with the soap still on it. But as it turned out, no one was hurt.

Captain Smellie tried to reverse the ship and get off by going astern. Then he tried going ahead, and when that didn't work he sent all us men down into the hold. We had a lot of coal in 100-pound bags taking it up north, and he had all down, clerks and everybody, dumping that coal overboard to try and lighten the ship, but it didn't help. Then about four or five hours later a storm started to come up. The captain saw he couldn't get the ship off the reef where it was grounded, it was pounding on the rocks, so he got all the lifeboats lowered from the davits, and he ordered us all up on the top deck.

We were all given new instructions about which boats we should be get into, either the lifeboats or the whale boats we were carrying. There were lots of boats. I think the ship carried six lifeboats and all of them had Kelvin engines, which were really good engines. And then besides them we had a lot of whale boats that were being taken north to sell.

We had enough time to get most of the stuff what was in our cabins. We took everything we could, like grub and tarps and everything like that, because we knew we would be a while on this island we were going to make for; it would be some days before any help would get to us. We did the usual thing-- it was women and children in the first lifeboats put in the water and one or two of the boats were filled up right away with provisions to carry ashore.

The captain was quite excited, actually, yelling and giving orders. For instance, when they were getting into the lifeboats, his steward came out of his cabin with a typewriter, and the captain took the typewriter and just threw it overboard!

An Arctic Man: The Classic Account of Sixty-five Years in Canada's North

On his return to Ardrossan the ship's cook gave the following eyewitness account of the disaster to the local paper:

The captain was on the bridge at the time and gave the signal for all hands to man the boats. There was no excitement. The captain kept on smoking his pipe and coolly issued his orders, which were promptly executed. The provisioned boats were ready for us to abandon ship and the women and children were first put into the boats.

Nancy Y. Middleton,

Time Colonist, 18 August 1985

On 22 July 1927 the Marconi wireless station at Smoky, Labrador received an SOS from Bayrupert stating she "was fast on the rocks in latitude 55.9 north, longitude 59.59 west" or halfway up the Labrador coast."

The Wireless Operator, J.W. Bygroves, who would prove a true hero of the whole affair over the coming days, sent out an SOS and wired HBC in London, and reported that the nearest ship, Moveria, was 450 miles or two days distant. Capt. Smellie ordered stores and blankets put into the boats and six lifeboats were lowered and the three women and six children aboard were first to embark them and the little convoy made for the Farmyard Islands, some nine miles distant. Capt. Smellie, Bygroves and nine crew remained aboard but later that evening with the fear the ship might break up if the weather changed, made for the Island in the one remaining lifeboat. Upon arrival at the Island, he found "the passengers and crew had been made comfortable in tents beside a huge fire on the island. All supplies has been landed in a smooth cove, and sailors and stokers had rigged up tents against the wall of a cliff." (Arctic Command).

The motor lifeboats towed the whale boats and the Farmyard Islands were reached in about three hours. One of the Newfoundland mates aboard who had fished in these waters picked the beach to land on the four by six mile island. Tents were rigged up or others, including her HBC clerks, were stuck sheltering under a tarp in the foggy and rainy weather.

On 23 July 1927, it was reported that except for Capt. Smellie and nine men, the passengers and the crew had been evacuated by ship's boats to Farmyard Island and that the ship "was pounding heavily and making much water fore and aft. She had jettisoned her cargo which was floating around. The position of the ship was 14 miles north of Cape Harrigan and the steamer Moveria, 360 miles to the west, was proceeding towards Bayrupert at a speed of 12 knots and additionally, the Newfoundland Government has ordered the passenger steamer Kyle (1913/1,055 grt), Robert Reid Co., already on the Labrador coast, to proceed to the scene." As she was closer, Moveria was advised to continue on her voyage.

Captain Smellie wired on 23 July 1927:

Bayrupert struck uncharted rock in lat. 55 59 No., long. 59 59 W. Held fast and bumping heavily. Will do all possible save ship. Now jettisoning cargo.

Bayrupert total loss. Crew and passengers landed Farmyard Island, self standing by with ten men. Weather fine. Engine-room and No. 3 hold full water. Can you arrange salvage cargo. If weather gets bad will land Farmyard Harbour. All crew and passengers safe.

At dawn on the 23rd, Smellie and a crew of volunteers returned to Bayrupert to raid her for provisions, wood and coal for the survivors as well as the six pigs, six sheep and a couple of cows even who were taken to the island.

What really did get in trouble was that the captain was coming down along the beach, probably to give us hell about something, and slipped in some cow dung and went ass over kettle. Myself and one of the second mates, we started to laugh like hell, so he made us stand there for half an hour without moving because we'd laughed. That Captain Smellie was very irritable, he was really nervous and excited and giving out orders. It seemed to us young fellow that anything that he could see we were doing wrong or he thought we were doing wrong, he'd be down out throats.

An Arctic Man: The Classic Account of Sixty-five Years in Canada's Arctic.

Wireless Operator Bygroves got the wireless set back in service using the emergency generator and with that, regular updates were sent out directly from the ship which Capt. Smellie visited every day with his officers.

|

| The Robert Reid steamer Kyle which rescued Bayrupert's survivors and later returned to salvage much of her cargo. Credit: Memorial University collection. |

Kyle reached the scene at 3:50 p.m. on 24 July 1927 and wired "Now proceeding to take crew off Farmyard Islands before night." Everyone was evacuated from the island except for the Captain, Chief Engineer, Radio Operator, Second Officer and Chief Steward who would spent most days aboard Bayrupert assessing her condition and continuing to scrounge provisions and food from her for their temporary island home which fortunately had a lake nearby with ample fresh water. Local Inuits arrived in whaleboats and engaged to help in the salvage and even most of the ship's furnishings and crockery was brought ashore.

.jpg) |

| The shelter made of canvas lifeboat covers and lumber from the ship that survivors erected on Farmyard Island. Credit: Mocassin Telegraph. |

But for Bayrupert the ensuing days reports told of a ship, impaled on a rock, rising and falling in the tide and swell and slowly dying.

On 24 July 1927, Lloyds relayed the following message from St. John's :

Nos. 1 and 2 holds dry, engine room stokehold deep tank and no. 3 hold tidal. Pumps compressor air plant and diver required. Suggest discharge cargo. No steam available. Hull above water perfect, ship held by rock under engine room. Twenty fathoms under stern, five under bow. If weather holds good splendid prospects salving ship and cargo. Removing deck cargo to Kyle now standing by. Halifax Shipyards offer us Reindeer I. Lord Strathcona, Ocean Eagle not available we suggest engage Reindeer I promptly. Our surveyor left on Susu due scene probably Wednesday (July 27).

Capt. Smellie wired HBC on 25 July:

Bayrupert: position unchanged. Nos. 1 and 2 holds dry. Stokehold and engine room full and tidal, no. 3 hold and deep tank full and tidal. Ship held on rock amidships, 15 fathoms water under bow, 20 fathoms under stern. Weather fine. Have commenced to salve cargo and land Farmyard Island. Should weather get bad ship expect will break. Hope very poor of refloating. Am trying to get fishing schooners assist in salvage work and land at Farmyards or Hopedale.

Since accident to vessel good weather, position of vessel unchanged, hull perfect above water level. With prompt salvage vessel may be saved. Cargo in Nos. 1 and 2 holds perfect, No. 3 hold full of water level. Local fishing vessels each 110 tons require guarantee 7000 dols. Salvage cargo or attempt. If ship saved damage will be considerable.

|

| On Farmyard Island: left to right: (undentified but possibly Capt Stuart of the underwriters,), Chief Engineer Ledingham, Second Officer and Capt. Smellie |

On the 26th, Lloyds relayed the following updates from Capt. Smellie:

Labrador cargo in no. 2 hold now full of water. Only no. 1 remains dry. Bowrings advise making preparations for salving, hull above waterline perfect and weather fine.

Kyle has no appliances for salvage work, can proceed on voyage. Understand owners recalling her and she sailed on the 26th via Farmyard Island, for St. John's, where she arrived on the 30th.

On the 27th, Smellie provided an initial accounting of the ship's cargo:

All cargos for Cartwright, Rigolet, North West River, Makkovik, Hopedale, Davis Inlet, Nain, including Mission, landed at Cartwright. Cargo salved by us and place on board Kyle: 1 dorry, 4 jollyboats, 2 icepunts, 1 whaleboat, 50 canoes, 5 cases of furs from Hopedale and Makkovik. Kyle still standing by, good weather, situation same as Telegram 5 (26 July).

It was further reported that salvage vessel Reindeer I would proceed from Halifax "as soon as steamer carry coal secured, have difficulty obtaining steam, no motor schooner available." and it was not until the evening of 27 July that Reindeer I and the chartered Dominion Shipping left Halifax.

.jpg) |

| The wreck of the Bayrupert. Credit: Mocassin Telegraph. |

The ship's condition began to deteriorate as reported by Capt. Smellie on 28 July 1927: "No. 1 hold now shows 7 ft. water. All other holds full water. Hull above waterline perfect. Water perfect. Weather fine. Steamer Kyle should not take our lifeboats, these remain Farmyard Island. Emergency dynamo used for wireless transmission." The following day, Capt Smellie wired "This may be last wireless transmission. Emergency dynamo being ruined owing to list of ship. Position unchanged, weather fine."

The salvage steamer Reindeer I arrived at St. John's from Halifax on 31 July but had to recoal there before proceeding north. On the 31st it was reported that upon the arrival of Kyle at St. John's that day with Bayrupert's crew and passengers (excepting the Captain, Chief Engineer, Second Officer, Wireless Officer and two others) that her 'deckhouses were showing sign of strain.'

|

| The Bayrupert lay far out to sea and at high tide, the waves broke right over her. Credit: The Beaver. |

Meanwhile, the fine weather that had prevailed since the grounding began to deteriorate with strong northeast winds on 31 July 1927. On 1 August Bayrupert was reported as "rising slightly high water, holds and engine-room filling to shelter deck. Prospects of salvage depend on weather owing exposed position." The next day Capt. Smellie advised: No. 1 hold nine feet of water, other holds tidal. Weather fine. Now salving foodstuff, landing Farmyard Island. Ten Hopedale motor boats and natives assisting.

Reindeer I arrived at the scene on 3 August 1927 and put a diver over the following day. This resulted in a rather grim assessment indeed: "All compartments now full, starboard side crushed up to bilge keel, engines boiler practically detached blocked from ship and resting on rocks. Ship now showing signs of breaking in two. Bad weather causes continual working and straining, engine-room bulkheads badly buckled. Upper deck set up and bodily to starboard. Salvage officer agrees salvage impossible. Will endeavour salve all possible cargo equipment with Susu when she arrives. Bayrupert's wireless may cease momentarily."

With no salvage possible, Reindeer I departed the evening of 5 August 1927 for St. John's, "services no longer required," and the arrival of Susu to salvage any remaining cargo and fittings was expected the following day.

On 8 August 1927 Capt. Smellie wired: Twelve Friday [5th]." Ship total loss. Now salving instruments. Coastal steamer expected here to-day salve all cargo possible." That day, Reindeer I returned to St. John's and her captain, Capt. Featherstone, reported that when the diver went under the wreck, "he found that the Bayrupert had practically broken in two, with her boiler and engine on the rock, her stern and bow being afloat. According to Capt. Featherstone it would have been possible to get the ship off but for a storm the night previous to his arrival ripping her bottom open. He believes that that with the next storm the aft portion of the ship will slide off the rock and sink." (The Evening Telegram, 9 August 1927).

|

| Credit: Evening Express, 8 August 1927. |

Some 50 members of Bayrupert's crew arrived at Liverpool from St. John's aboard the Furness liner Nova Scotia on 8 August 1927.

Kyle and the veteran Meigle (1881/836 grt), continued to salvage cargo and the former landed 71 canoes and boats at St. John's by 11 August 1927 and this and some other recovered Bayrupert cargo was held for loading onto Nascopie which was due at the port from the north on the 20th. When Kyle arrived that day, her salvaged cargo including 103 casks of tinned lard, 98 cwt sacks of flour, 90 cases of tinned milk, 18 cases of matches (some wet), 12 cases of butter, 38 cases of ammunition, 10 rolls of roofing and five cases of tea.

|

| Together with Kyle, the Robert Reid Co. steamer Meigle (above) did most of the salvage of Bayrupert's cargo and fittings. Credit: Memorial University collection. |

On 19 August 1927, Meigle reported she was salvaging Bayrupert's cargo but this was cut short with the onset of strong east winds. On the 24th she wired that 300 packages of stores had been salved and that almost all the cargo and coal left was underwater.

Even a Labrador legend, Dr. Wilfred Grenfell, the "Medical Missionary," and famous for his little hospital ship Strathcona II, was in on the scavanging of Bayrupert:

As we were steaming north three weeks later, we suddenly sight a strange steamer on the horizon, apparently broken down. It proves to be same s.s. Bay Rupert, still transfixed like St. Simon Stylites on his pole. We paid many visits to the abandoned ship, and my crew of 'wops' thoroughly enjoyed the dangerous adventures of those days. We salved a great many supplies of much value to the Coast. Every variety of goods, from hardwood sledges to barrels of gunpowder, and from new guns and rifles to cases of chewing gum, was included. Above all, we got the most wonderful series of moving pictures from every point of vantage, including her own masthead. Varick Frissell climbing up the mast and balancing on the truck while he took them. To help some of the Eskimos on that northern section of the Coast, we mothered a number of their small boats out to the wreck, and I was rewarded the first day by catching a warrior incontinently beating open a box of T.N.T. with the back of his axe, 'to look what was in it.'

None of us will ever forget the high living of those days when Strathcona lunches included Kraft's cheese, mango chutney, nuts, oranges and unlimited hams and tongues.

As it was my task from the bridge to keen an eye on the weather and on the deserted Strathcona anchored on the shoulder of the same shoal, I had been able to collect my valuable hardwood, plate-glass windows, and also a good of mahogany from the main staircase and lounge, through later some of this had to be thrown overboard and towed to the Strathcona when our rowboat was already carrying a full load.

On the bridge I discovered a beautiful bath in the captain’s bedroom, and yielding to temptation decided to try and salve it. After getting it loose with great difficulty, I found that it would not pass through either of the two doors leading out on the deck. However, by taking off its legs and chopping a large hole through the sitting-room wall, then removing the door and its hardwood lintel and uprights, we dragged the prize out at last. The ship was at a considerable angle, and we and the tub literally glissaded together down to the lee rails. Forty feet below us lay the little boat. By that time it was too late to risk trying to lower our latest booty into her, so I lashed it to the rail and left it, hoping to reclaim it the next time we came aboard the wreck. However, when we returned to look for it, it was gone — to the bottom of the deep blue sea as we surmised.

A month later, long after the wreck had sunk, we happened to spy that bath high up on a beach, near the spot where we had anchored. A Labrador settler friend told us he had found it lashed to the rails and had thought it was abandoned.

‘But it was mine,’ I argued. ‘I can prove it. Here are the four legs I unscrewed from it. Anyhow, what good can it pos- sibly be to you?’

‘Oh!’ said he, ‘I thought perhaps my wife might like to have a bath some day.’

Forty Years for Labrador

Nascopie arrived at St. John's from the North on 24 August and loaded the cargo landed by Karmony which was a duplicate outfit as to that lost on Bayrupert and she would sail as far north as Churchill.

Meigle docked at St. John's on 31 August 1927 "bringing practically a full load of salvaged goods. Capt. Burgess reported that the Bayrupert had not broken up when he left but all the holds were full of water. The Meigle was alongside three days and had to shift from hatch to hatch according to tides. Gasoline and other goods had to be left as they could not be hooked up out of the water. In any kind of rough weather the sea comes in over her starboard side and breaks over the port side." (Evening Telegram). Among those aboard were Capt. Smellie, Chief Engineer Ledingham, the 2nd Mate and Marconi Operators J.W. Bygroves as well as Capt. Stuart of the underwriters.

Of their survivors' "desert island," Capt. Smellie later observed: "Among the salvage were sixty cases of good whiskey which we brought to the island from the Bayrupert. And we didn't touch a drop." (Arctic Command).

The first auctions of salvaged stores from Bayrupert, were held at St. John's on 19-20 September. On 2 November was an offering of cargo and fittings including 30 life belts, four skylight covers. Tenders were invited on 23 December for the ship's salvaged wireless equipment, two ship's clocks, 1 ship's barometer, steel and manila hawsers and one jolly boat.