Gallant, stout-hearted, patient, she is the uncrowned queen of the Arctic, and she has a history unparalleled in northern navigation. Some day her story will be written, and it will be worth reading.

The Beaver, March 1938

Someone should write up the Nascopie. She was a real ship.

James G. Wright, Chief of Eastern Arctic Patrol, 1947

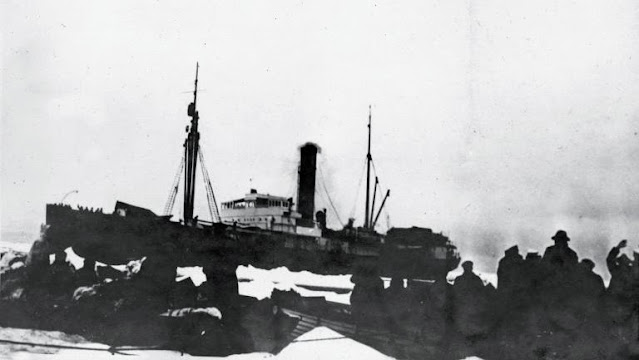

Of the Edwardian Era's remarkable generation of merchant ships, few served longer on the same route as H.B.S.S. Nascopie. Faithful flagship of the "Ancient and Honourable" Hudson's Bay Co. (chartered in 1640), she remains a legend in the True North yet sadly unappreciated elsewhere. Commissioned the same year the 46,000-grt Titanic encountered a single iceberg and managed to both hit it and founder on account of it, the 2,520-grt Nascopie went on to spend her entire 35-year career safely navigating the bergs and epic ice fields of the Arctic from the White Sea to the Labrador "front," Baffin Land, Hudson Bay and the Northwest Passage.

"As faithful as the seasons," and lifeline to the isolated trading posts and Inuit communities that formed the northernmost reach of The British Empire, Nascopie carried the post "factors," missionaries and "mounties" who came to depend on her once a year calls, irrespective of weather or war, for provisions, coal, mail and medical care. She was the linchpin of a unique barter system between the Inuit hunters, trappers and whalers who made the Hudson's Bay Co. the longest surviving of the chartered companies that formed the commercial foundation of the Empire.

The company and vessel were British yet with her mostly Newfoundlander crew, participation in the annual seal fishery and long association with St. John's (where she was initially registered), Nascopie was every bit as much Newfoundland's whilst having equal claims as Canada's Ship of State performing the annual Eastern Arctic Patrol from 1933-47 which maintained and defended the Dominion's "True North, Strong And Free," and even rating a mention in the seminal portrait of Canada at war, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The 49th Parallel (1941) starring Laurence Olivier and Leslie Howard. Nascopie even pioneered Arctic pleasure cruising in the 'thirties.

This, then, is the story of the modest yet stalwart little ship that more than earned her place in the history of the remote regions she served and in the hearts of those to whom she was indeed The Lifeline of the Arctic...

H.B.S.S. NASCOPIE 1912-1947

|

| Nascopie by John Ellison, The Beaver, Autumn 1980. |

|

| Nascopie at Port Burwell in 1934. Credit: Max Sauer, Jr. photograph, The Beaver. |

|

| Nascopie sails from Montreal in July 1939. Credit: Archives of Manitoba |

Year by year the 'Honourable Company' had pushed out its frontiers and established new posts in the far north. Year by year it was on the Company's ships that our men were entirely dependent for their year's supplies of food and equipment, and also (so important in that life of exile) for their mail.

Patrick Ashley Cooper, Governor of Hudson's Bay Co., 1931-1951

Arctic Command.

To put the Company's transport on a proper footing, and to avoid the necessity of chartering extra tonnage to carry the increasing quantities of provisions and stores year by year, your directors have entered an agreement whereby the Hudson's Bay Company will own a majority interest in a steamer which is being constructed for Arctic navigation. This will ensure sufficient suitable tonnage to the Company for some years to come.

Lord Strathcona, Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, 10 July 1911.

"For some years to come" indeed and this understated announcement would produce a vessel that not only would go on to serve the Hudson's Bay Co. for 35 years, but in doing so, create a True North legend, ranking her as not only one of truly great Canadian and Newfoundland ships, but among the most successful of all Edwardian liners yet the smallest and humblest of them all… H.B.S.S. Nascopie.

The fancy of French and English dandies of the mid 17th century for felt hats was good a reason as any to inspire the exploitation of North American wildlife especially in what is now Canada and where Inuit and Indians had long engaged in hunting and trapping of an abundance of furry animals populating the virgin wilderness. The demand for felt was especially strong in France and two French traders, rebuffed by their own government, got the backing of Prince Rupert, cousin of England's King Charles II, for their first expedition. From the onset, watercraft of all description, from sailing vessels to canoes and kayaks, were integral to the enterprise, providing not only the means to transport the pelts home but to reach into the hinterlands of the vast expanses of North America, laced by rivers, creeks and with lakes and bays as large as inland seas.

|

| Nonesuch returns to London with the first "return" of fur hides from Rupert's Land, 1668. Credit: www.hbcheritage.ca |

So it was that Nonsuch and Eaglet were dispatched from London on 5 June 1668 to the mouth of what was called Rupert's River where it enters James Bay. The entire expanse of what is now known as Hudson Bay was named Rubert's Land and in 1670 of the "Governor and Company of Adventurers of England" which formed the foundation of what came to be known as the Hudson's Bay Co. was created.

From the onset, HBC was organised as a joint-stock company with government-like central bureaucracy. "At the annual General Court (Annual General Meeting in today’s terms), shareholders elected a governor and committee to organize fur auctions, order trade goods, hire men and arrange for shipping. The London-based governor and committee set all the basic policies implemented in Rupert’s Land, basing their decisions on annual reports, post journals and account books supplied by the officials on the bay. The General Court also appointed a governor to act on their behalf in the bay area. In Rupert’s Land, each factory (trading post) was commanded by a chief factor (trader) and his council of officers." (Canadian Encyclopedia).

.png) |

| Map of the extent of the posts of Hudson's Bay Co. extending right across Canada and north to the Eastern and Western Arctic. Credit: www.hbcheritage.ca |

HBC was for most of its initial 250 years essentially a trading company built on barter between the local Indian and Inuit trappers who, in exchange for pelts, obtained manufactured goods like tools, guns, textiles (which began the company's famous range of blankets and clothing) and food. HBC even minted its own currency to facilitate the barter arrangement, the Made Beaver coin having the value of one male beaver skin. The nomadic populations would come to local trading posts, established by the HBC usually at the mouths of rivers that fed into James Bay and Hudson Bay. These isolated posts formed the network which defined the Company and which was wholly dependent on watercraft to serve. Moreover, posts were added or abandoned as demand warranted and into the 20th century HBC expanded ever northward to encompass Baffin Land. Nor was HBC confined to the eastern Arctic and its network of trading posts extended right across to the Pacific and western Arctic Ocean.

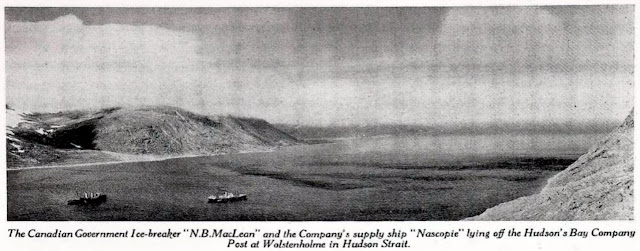

Hudson's Bay Co.'s network of trading posts in the Eastern Arctic began in 1909 with the establishment of that of Wolstenholme by Ralph Parsons, Fur Trade Commissioner, who went on to create 28 posts in a remarkable 40-year career including along the coast of Hudson Strait and Baffin Island, among them Lake Harbour (1911), Cape Dorset (1913), Stupart's Bay, Frobisher Bay (1914), Pangnirtung (1921), Pond Inlet (1921), River Clyde (1923), Arctic Bay (1926) and re-established in 1937 and Fort Ross (1937).

|

| "The Returns": bales of white fox skins being loaded aboard a barge to take out to Nascopie anchored in the bay, 1938. Credit: Lorene Squire photograph, The Beaver. |

The core of HBC yearly business was "The Outfit" which constituted the entire annual import of the necessities to keep each post supplied, fed and fueled as well as stocked with the consumer goods and provisions bartered with the native hunters and trappers in exchange for "The Returns" which were the exports of furs, seal and whale oil, ivory (mainly walrus tusks) etc. A typical c. 1910 "Outfit" might cost the company $90,000 ($2.8 mn. c. 2022) and the "Returns" worth $400,000 ($12.7 mn.) These were the profits which made trading in such remote and difficult places worth it to the Governors and shareholders.

In this, HBC was no different than what formed the foundations of the British Empire: private companies regionally based and wholly dependent on maritime trade and transport. What was different, unique even, was the region, seas and climate in which they conducted their business. At the height of the company's northern operations, Nascopie was trading just 800 miles south of the North Pole and with the exception of Chesterfield Inlet, all of the ports visited were above the tree line. There was no wood and save for hunting and some fishing, no grown food and few domesticated animals other than husky dogs. Everything to sustain a post for an entire year had to be brought in on a single annual voyage encompassing 10,000 miles.

|

| Working cargo Hudson Bay style: Inuit women and children hauling ashore a large crate landed by boat from the anchored Nascopie, 1925. Credit: G.E. Mack photograph, McCord Stewart Museum. |

Moreover, except for Chesterfield Inlet where a ship could go alongside a rather extemporaneous wooden jetty, all the calls... 15 or so per season... involved working all manner of cargo at anchor and many of the "ports" were just a stretch of beach with a 20-40 ft. tide and with no lighterage available, the ship had to use two of her lifeboats lashed together and with timbers athtwart to form a deck and towed by the ship's own steam launch. Nor were there any stevedores... HBC deck crew, even the officers, did the unloading themselves aided by Eskimo labour, mostly women.

At the fringes of Empire, the Arctic regions of British North America were poorly charted and largely bereft of navigational aids, the already challenging route made worse by the ever expanding number of posts in Baffin Land whose coasts were beset with uncharted rocks, many the pinnacles of underwater mountains. Indeed, Nascopie would, like Bayrupert, be ultimately be claimed by rock not ice.

|

| Nascopie "in the ice" at Port Burwell, 1920. Credit: Frederick W. Bercham photograph, McCord Stewart Museum. |

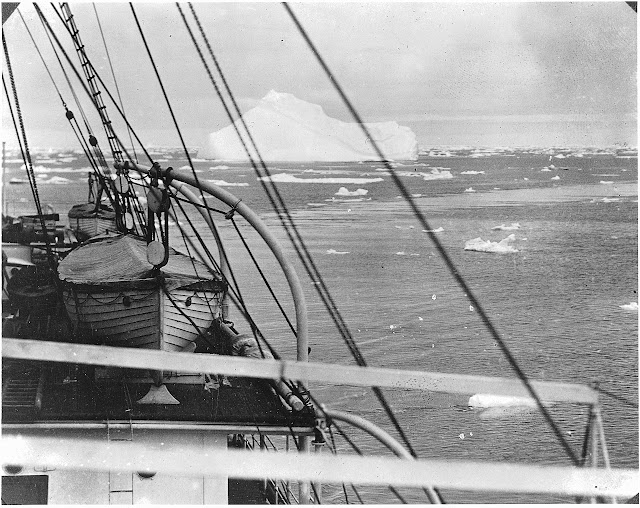

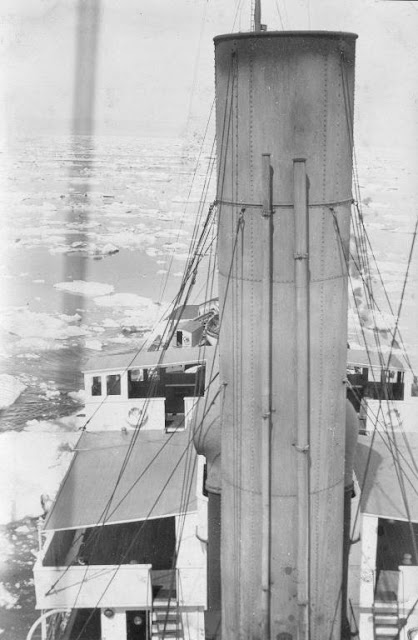

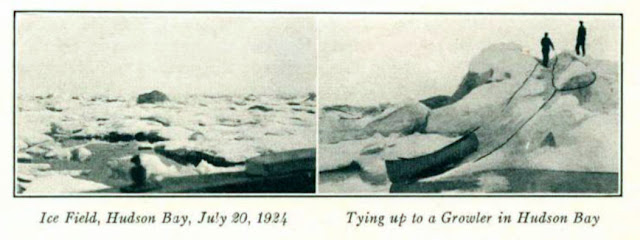

The main danger to navigation was still ice even during the summer months, the only time the Hudson Strait was passable. Even then, HBC ships might encounter dozens of bergs whilst growlers and field ice were common. The real barrier were the epic expanses of heavy pack ice, often five-foot thick. These packs moved with the swift tides and currents and could envelop a ship which once "nipped" could literally be crushed. In addition, encased in a moving icepack, the ship, too, was transported unwilling along with it, risking crashing into reefs or against shorelines. On one occasion, Nascopie travelled 40 miles off course without turning a screw when trapped in a moving ice pack off the Button Islands, north Labrador.

All this meant that the essential give and take of the Company business, the "outfit" and the "return" were concentrated in a tight July-November time frame and accomplished in one or, at most, two voyages originating in Montreal in mid July and usually ending in St. John's, Newfoundland in late September. There, the ship would usually proceed to England with its valuable fur cargo. The "outfit" of 2,000 or more tons, resulting in a "return" of 45 tons worth three or more times in value.

There were few "milk runs" in the British merchant service c. 1910 but none as challenging as taking HBC's yearly "Outfit" into the northern reaches of the Empire where, appropriately enough the HBC houseflag was a defaced Red Ensign and the Company's officers and men-- British, Newfoundlander and Canadian-- owed nothing to any other in the Merchant Navy for seamanship, steadfastness and resourcefulness.

Almost from the onset, HBC's unique specific marine requirements mandated special designs including their own designed and made canoes and famous Scottish-built "Peterhead" whalers, so named for where they were constructed. Deep sea vessels, including schooners and steam assisted barques, were usually built of ironwood and exceptionally strong forward to withstand being "nipped" in the ice. But in the steel and steam era, HBC built few deepsea vessels specifically for the purpose given their employment was but one round voyage a year, and, instead would either charter ships or purchase suitable ones from previous owners.

In 1910, the principal HBC ships delivering "the outfit" were the wood steam-assisted barquentine Discovery (1901/751 grt) and the wood steam-assisted barque Pelican (1877/638 grt), the later having been originally a Royal Navy warship and the former had been engaged in south Polar exploration before being acquired by HBC.

Here, HBC's great rival in the fur trade, Revillon Freres, stole a march on them by chartering the pioneering Adventure (1906/1,761 grt), the first of a new type of steel icebreaking merchantmen designed for Newfoundland's annual seal hunt and general trading in the northern latitudes, for their own annual supply run to Hudson's Bay in beginning in summer 1908. She proved ideal for the purpose and was chartered each succeeding year up to The Great War.

In 1910 I remember, there were rumours among the crews of the Pelican and Discovery that a new ship was being built for the Company. In 1911 it was an accepted fact. Many were the discussions as to what she would be like. Would she be as good and powerful like the Adventure? The Adventure had once or twice passed the Pelican in the ice on the Labrador Coast. She used to be chartered each summer by Revillon Freres to supply their posts in Hudson Bay. To be passed in the ice by a ship carrying the opposition posts' supplies was like searing the soul with a red hot iron. The Pelican would do her best, but low power and sails and wooden walls had no chance against modern engines and steel. All we could was to heartily curse the Adventure in one breath, and pray no ice and a good fair wind with the other.

Captain G.H. Mack, The Beaver September 1938

Amid booming business, there was clearly a need by HBC for their own specially built, steel icebreaking cargo vessel large enough to accommodate the entire annual outfit delivery and have the structural capabilities to do so in almost all conditions. She would be designed and constructed along the lines of Adventure and prosecute the annual seal hunt from Newfoundland March-April and then underake the annual supply trip north July-October. Indeed, there were other similarities with this seasonal employment and HBC's requirements as Adventure had already proved for Revillon Freres and here the complimentary operational needs would lead to corporate cooperation as well.

|

| Credit: Wikipedia |

Not only was the sealing season compatible in the calendar of the HBC's annual "outfit" delivery, but its requirements as far as vessel were the same. Finding employment for sealers out of season had always been a challenge and thus a marriage of convenience between HBC and Job Bros. was arranged, the offspring of which would be the new ship which reflected the compatible requirements of both. Job Bros. (dating to 1750) of St. John's, along with Bowring Bros., dominated the island Dominion's traditional maritime trades of fishing and sealing.

A new joint enterprise, The Nascopie Steamship Co. (NSC) was formed in August 1911 with HBC holding 117 shares and Job Bros. 103 with a working capital of $200,000. In addition, Job Bros. would act as the agents for the new ship and use their considerable expertise and contacts to find charters and odd employment outside of the July-November HBC "outfit" voyage and Job. Bros. March-April sealing. HBC, Job Bros. and others would, in effect, charter the ship from NSC on a monthly basis as per their needs.

From her inception, the ship was called Nascopie after the "people beyond the horizon" who inhabited the sub-Arctic regions of what is now northern Quebec and Labrador. The association between the Nascopie and the HBC dates from establishment of the first trading post at Fort Chimo in 1831. Ironically, given the dutiful qualities of the ship named in their honour, the Nascopie initially were resistant in adopting to the commercial hunting and trapping enterprises of the HBC.

Messrs. Job Bros. & Co., are building a big sealer, twice the size of the Beothic, and about the size of the Florizel.

Harbour Grace Standard 2 June 1911

St. John's, Nfld., papers announced that orders have been given by local firms for the construction of two new sealing steamers. Hon. W.C. Job, of Job Brothers, placed an order with Swan & Hunter for a steamer to be finished by December 31, and reach St. John's during January next. She will be called the Nascopie, after the tribe of Indians of that name. The Nascopie will be fitted with electric searchlight, and her hatches will be specially constructed for the loading and discharging of cargo. Capt. George Barbour, who has been so successful in the Beothic, will have the new steamer, which will be about the same size as the Florizel.

Gazette, 6 June 1911

Job Bros. have placed an order for a whaling steamer to be called Nascopie. "She will be equipped with electric searchlight, and be fitted with special hatches for the quick loading and discharging of cargo. The contract calls for completion Dec. 31, so that she may reach Newfoundland in January 1912."

The Railway and Marine World, July 1911

If officially announced during HBC's July 1911 annual meeting, the news of Nascopie's order and most of the details of the vessel that were released prior to her completion, were widely circulated in the Newfoundland and Canadian press, although almost all in the context of her sealing role for Job's.

The order went to Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson, Newcastle upon Tyne, which like most British yards, was enjoying a halcyon era and although most famous for Mauretania (1907), was then building Franconia and Laconia. The little steamer they would build for HBC/Jobs would outlive all three in commercial service, but today is one of the most overlooked of all Tyne-built ships.

Job's new sealing steamer, Nascopie, which was launched at Newcastle-on-Tyne yesterday will be one of the finest ships of the sealing fleet leaving this port. She will have a speed of 14 knots, is over 2,000 tone register, and was built by Messrs. Swann, Hunter & Co. She will be one of the finest ice boats of the fleet having been specially built to resist the Arctic floes, and in the summer season will ply in Hudson Bay. Capt. George Barbour, of the Beothic, will command her at the seal fishery, and Captain W. Wineor will take the Beothic. The ship will leave for this port early in January to get ready for her spring's work.

Evening Telegram, 8 December 1911

Her final plans inked on 28 April 1911, the date of the laying down of no. 870 at the Neptune Yard, Low Walker, of Swan Hunter & Wigham Richardson is obscure, but she was most likely under construction before the month was out. Little time and even less publicity was invested in her building and subsequent launch on 7 December with nary a mention in the press. If no. 870 was afforded a christening or if even anyone other than the shipyard manager and workers was in attendance, is not known. It was all rather a desultory beginning and HBC seems to have treated construction of the ship as they would another Peterhead whaler.

As an example of the shipbuilding activity prevailing on both banks of the Tyne at the present moment the output for Messrs. Swan, Hunter, and Wigham Richardson from their Wallsend Shipyard and Neptune Shipyard, Walker, last week may be cited. From their Wallsend Shipyard they despatched two large twin-screw steamers for Liverpool owners:, viz., the Indrapura liner and the Cunard liner Laconia, together representing nearly 29,000 tons, as well as H.M. torpedo-boat destroyer Sandfly, taken over by the Admiralty after a successful acceptance trial on Wednesday. The week was also marked by the launch of the first of three floating docks building for the British Government. At the company's Neptune Yard the sealing steamer Nascopie, a vessel 285 ft. long and with a speed of 14 knots, was launched to the order of Messrs. Job Brothers, Liverpool, in conjunction with the Hudson Bay Company; and the mail and passenger steamer Jaquislsco, bult at the same yard for the Salvador Railway Company, ran a successful trial trip burning oil fuel. Six vessels, of so varied a character, in a single week must be surely a record.

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 14 December 1911

Messrs. Job Bros. & Co. yesterday had a wire to the effect that the s.s. Nascopie had made her trials trips on the Tyne and that they were eminently satisfactory. The ship developed fine speed, averaging nearly 14¼ knots, which is a good deal more than the contract called for… The ship having such fine speed should make a good run out here.

Evening Telegram, 26 January 1912

On the trial trip, although the sea was rough and the weather decidedly unfavourable, she attained a speed of over 14 knots, considerably in excess of the contract requirements.

Page's Weekly, 2 February 1912

Little time was wasted in completing Nascopie even by Edwardian shipbuilding standards and on 24 January 1912 she ran her trials in the North Sea. The official party aboard included Mr. A. Hamilton and Mr. Adamson of Messrs. G. S. Goodwin and Co, Messrs. R. and T.B. Job, of Liverpool and Newfoundland, and Mr. Ingram, of the Hudson Bay Co., and the builders by their directors, Mr. Christie and Mr. G. F. Tweedy. Nascopie cranked out an impressive 14.10 knots, a good two knots over her service speed and one over her contract speed.

|

| Built for strength not speed, Nascopie still managed a respectable 14.10 knots on her trials. Credit: Page's Engineering Weekly, 2 February 1912. |

Capt Waite is delighted with her and believes her to be a superior ship to the Beothic. The apartment of the Marconi operator and the wheel house are on the upper bridge, and the chart room and captain's room are immediately below this and are comfortable and fitted with every modern convenience. The rooms of the other officers are on the main deck, on the starboard side in the amidships section of the vessel, and the engineers' rooms are on the opposite side, while those of the firemen and sailors are forward and are also very commodious and comfortable: her cabin is fine, large and excellently equipped. She is lit with electricity; her engines are of a very powerful type, and all who have seen her believe the ship will give a good account of herself. She is a fine vessel in appearance, and we congratulate the owners. Messrs. Job Bros. & Co. on possessing such a splendid boat.

Evening Telegraph, 19 February 1912.

Work there was aplenty for Nascopie and all who manned her for all her 35 years for what was indeed a pack mule of a vessel that owed nothing to any other for strength and steadfastness, an exemplar of Edwardian naval architecture and English shipbuilding craft no less than a Mauretania. These were the ships that maintained the commerce of the greatest world economy-- The British Empire-- at its zenith and Nascopie's Red Ensign flew in its northernmost reaches.

One of the most overlooked innovation of Edwardian marine engineering and naval architecture was the icebreaking cargo-passenger vessel and the only one specifically originated in British North America. Hulls strengthened for navigation in loose ice, be they built of wood or steel, were not uncommon but one specifically for icebreaking, by designing the bows so as to rise over the floes and crush heavy ice packs with the sheer weight of the hull and power of the engines yet still function as a practical and economical cargo and passenger carrier, was something entirely new. The design was evolved in the oldest of all England's overseas colonies, Newfoundland, where the annual seal fishery put ships and men where others might avoid... right into the heaviest ice packs and floes and tested the stoutest ships and seamen to accomplish. The "hunt" lasted but six-seven weeks a year so the ship would have to find more conventional employment the rest of the year.

If Russia became the birthplace of the icebreaker and still has priority in the matter, Canada (or rather, England, because the ships operating in Canadian waters were built at its shipyards by overseas order) became the “mother” of icebreaking ships. It cannot be said that there were no such ships before at the end of the 19th century in the ports of the Baltic, America, and Russia there were many ships capable of operating in ice. However, there were very few specially built for permanent cargo and passenger operations, taking into account the ice factor.

The Canadians needed a fleet of medium-capacity steamers capable of almost year-round independent operation between Newfoundland and the mainland, in areas where encountering ice was common. Moreover, these ships should have been able not only to cross light ice (the hulls were reinforced), but also to carry a large amount of cargo and work freely at other times of the year in the Caribbean Sea or even across the Atlantic. The most powerful English shipyards solved the problems of their Canadian partners without any problems, and by the beginning of the First World War, such a fleet exceeded a couple of dozen ships operating in the waters of northern Canada.

Northern icebreaking ships of Tsarist Russia, R.V. Lapshin, https://naukatehnika.com/

In 1906, however, an enterprising ship owner of St. John's determined upon the construction of a steel ship of about 2,000 tons, of novel design and unusual strength, which he was convinced would prove even more effective amid the icefloes than the wooden crafts, the bow of this new boat being so contrived that she would slide gradually on to an icemass and break it down by her weight, instead of attempting to split it by attacking it with her stem, as was the usual practice previously. This ship, appropriately enough named the Adventure, proved a complete success and every year since her first season (1906) has prosecuted this industry with highly gratifying results. So complete, indeed, was the triumph of the experiment that the next year the same concern built two other steamers of similar class the Bonaventure and the Bellaventure, while another concern built the Beothic of the same type. Coincident with these accessions of the new ships, unfavorable seasons caused the loss of several of the wooden fleet, and whenever one of the latter vanished she was replaced by a steel fabric, for it now came to be realized that these new-type 'sealers' are destined to dominate the industry in the future.

A still more radical departure was made in 1909, when a ship of more than 3,000 tons--the Florizel--was constructed on the same lines, for the purpose of plying in the passenger trade between St. John's and New York all the rest of the year and engaging in the seal fishery during March and April. She cost $320,000 and in her second season broke all records with her catch, which was nearly 50,000 seals, or a third larger than the best previous total. Her owners, inspired by this, constructed a consort of the same size last year and for the same service--the Stephano--which is making her maiden trip to the ice fields now.

The owners of the Beothic, in conjunction with the Hudson Bay Company, developed yet another novelty--the Nascopie of 3,500 tons, intended for the present to operate in the seal fishery annually and to convey stores to the fur posts in Hudson Bay every summer and bring out the stock of peltries accumulating there, engaging in general transport work at other times with the idea, however, that when the Canadian Government builds a railroad to Hudson Bay she will be put into the work of freighting grain from Churchill to Europe and general merchandise back through Hudson Strait during the period of open navigation. She has been specially provided with sufficient bunker accommodation to enable her to make the transatlantic voyage, and will probably serve as the type for other ships of the same class in future years.

Journal of the Canadian Bankers Association, Vol. 12, Issues 3-4

In all, nine of these "steel sealers" were built-- Adventure (1905/4,000 grt), Belladventure (1909)/3,217 grt, Bonaventure (1909/2,800 grt) for A. Harvey, Beothic (1909/2,800 grt) for Jobs Bros.; Bruce (1912/3,000 grt) and Lintroz (1913) for Reid & Co. and Florizel (1909/3,081 grt) and Stephano (1911/3,449 grt) for Bowring Bros.-- the first commercial steamships built with icebreaking capability with the cutaway bows and extra heavy scantling and plating forward that characterised the type. And... Nascopie of 1912.

|

| Bowring Bros. Florizel (1909) was the first ship designed for passenger service and the seasonal seal hunt and had a full icebreaking hull and construction. |

Most of these had been designed by Messrs. A. Goodwin-Hamilton & Adamson, Ltd., Liverpool, who can be rightly be credited with the concept and the successful dynasty of such vessels that carried on through to the Red Cross liner Nerissa of 1926.

So it was that a Newfoundland inspired design formed the basis for something hitherto unique in the Hudson's Bay Co.'s 235-year history: a vessel purpose-built for their yearly "outfit" to regions and waters even more challenging than those at "the Front" of the Newfoundland seal fishery. They entrusted the design of the new ship to Messrs. A. Goodwin-Hamilton for all the right reasons and what was produced would prove among the most enduring and successful of them all.

|

| Nascopie on trials showing her light, graceful lines that gave no hint of what a tough little ship she was. Credit: Gijsha, shipinghistory.com. |

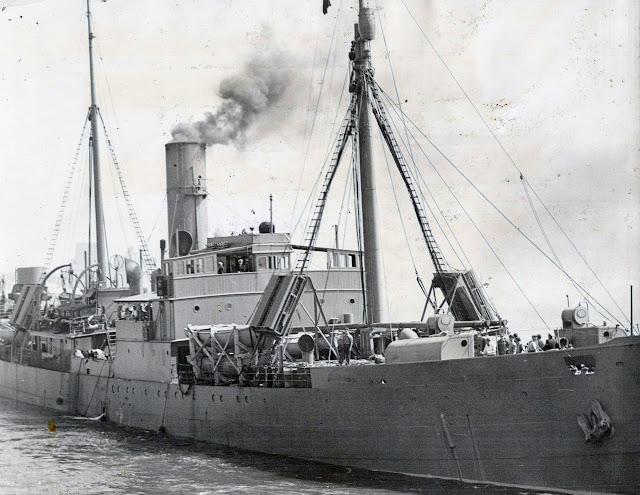

Goodwin-Hamilton & Adamson gave Nascopie light and lovely lines and minimal superstructure and in her handsome Job Bros. livery of light grey hull, white upperworks and black-topped buff funnel bearing their twin houseflags, she might be mistaken for being a tropical banana boat more than a seal hunter and Arctic supply ship. No one could mistake her quite extraordinarily tall funnel which was the first thing spotted miles distant on "Ship Day" at the HBC posts. "My first impression was what a long funnel she had. After looking around, I saw she was a very fine ship indeed…" Capt. Mack, The Beaver, September 1938. She had a very long fore deck which would prove much used for accommodating the often quite remarkable flotilla of boats, barges, cutters, whaleboats etc., some of considerable size, for transport to some of the posts.

Measuring 285 ft. 5 in. in length and 43 ft. 6 in. beam with tonnage measurements of 1,870 (gross) (as built, rising to 2,521 by 1928) and 1,520 (nett), Nascopie drew 17 ft. 6 in. forward and 21 ft. 10 in. aft when loaded, but was later listed as 21 ft. 7 in. forward and 24 ft. aft. That was about the draught limit for safe navigation off the coast of Baffin Land. Nascopie was only 20 ft. shorter than Florizel but had six inches more beam giving her a length to beam ratio of 6.8:1 reflecting the compromise between a true icebreaker and cargo-passenger with a fair turn of speed. Her displacement was an impressive 2,800 tons and Nascopie was a big strapping steamer for her dimensions and ideal for punching her way through whatever the Hudson Straits and Labrador front had for her.

|

| Nascopie's forward superstructure as she gets underway from Montreal for The North, July 1927. Credit: John M. Kinnaird photograph, McCord Stewart Museum. |

In her construction special attention was given to strength to fit her for forcing through the Northern ice floes, and she is the equal of any of the modern ships prosecuting the voyage. Her beams, knees, girders and staunchions are of unusual strength and thickness, her plates are of the best kind and are particularly heavy at the bows.

Evening Telegraph 19 February 1912

The toughness of Nascopie was legendary but it was accomplished by specification, engineering, plates, riveting and castings rather than hyperbole. By any standard, she was one of the heaviest-built merchantmen of her era and Newfoundland newspapers said she was "as tough as a Dreadnought."

The specifications tell the story: her scantlings or frames were spaced 12 inches apart from the stem to 100 ft. and then 16 inches aft, her plating was ⅝ inch thick but doubled from the stem to the engine room and she had an "ice belt" of one-inch plate right around the hull at the load line. One of the consequences of the icebreaking bow was often broken masses of ice flowing aft and damaging the screw and or rudder. Consequently, Nascopie's rudder post casting, 6½-ton four-bladed screw and shaft were 50% thicker and stronger than Lloyd's requirements. She broke screw blades just once... on her first sealing voyage... and not again in the ensuing 35 years.

She is excessively strongly built of steel, and her form, strength, and details of construction embody the latest practice for vessels intended to work amongst thick ice. Her stem is so formed that when she charges the ice she will glide upon it and crush it under her weight. The machinery, shafting, and propellers have all been made specialty heavy in order to cope with the shocks that she must receive amongst the ice.

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 27 January 1912.

|

| Builder's model of Nascopie. Credit: HBC photograph. |

More than materials, Nascopie had the same type of icebreaker bow profile that had been introduced with Adventure in 1905 and a lot of her lines were similar to Florizel of 1909 which she approached in size although being about 50 ft. shorter. This angled the underwater profile of the bows sharply back from the stem at the waterline to let the bow ride up over and on top of an icepack and crush it with the weight of the vessel as well as the forward thrust of the engines. This put enormous strain on the stem which was fitted with a very tough solid cast "shoe" riveted to the stem, as sort of ice battering ram. How any of her crew, berthed traditionally in the forecastle, got any sleep with the relentless pounding and shuddering of Nascopie punching her way through ice, is difficult to ponder.

|

| Nascopie rolling in the Atlantic off Newfoundland, 1930. Credit: John M. Kinnaird photograph, McCord Stewart Museum. |

She was built like a yacht. She couldn't keep on an even keel because she had no bilge-keels. She was design to slide over and past the nice and a bottom like a racing shell... She had to be a wallower, but she rode like a yacht in a gale, even though she often threw everyone out of their bunks. I slept on the floor more often than I can remember.

Captain Thomas Smellie

quoted in Arctic Command.

Nascopie was a real sailors' "seaboat" which could cleave high seas or thick ice and yes, roll. It was said she could roll even at dock or at anchor and a consequence of her flat slab sides quickly transitioning to a flat bottom which had to kept smooth to let her cleave ice floes and precluding the provision of roll dampening bilge keels. This also accounted for her occasional surprising showings of speed without the drag of bilge keels. Southbound when she was lightly loaded and low on bunkers, Nascopie could roll with the best of them especially on the final leg from Fort Chimo and down the Newfoundland coast to St. John's.

|

| Midships Section Plan of Nascopie, dated 8 May 1911. LEFT CLICK for full size scan. Credit: lrfoundation.org.uk/ |

|

| Deck Plan and Profile of Nascopie, dated 8 May 1911. LEFT CLICK for full size scan. Credit: lrfoundation.org.uk/ |

Nascopie had three holds (no. 1 15' x 12') and (no. 2 26.8' x 16' forward) and no. 3 (26.8' x 16' aft) with a total capacity of 129,779 cu. ft. or 2,500 tons. In the Second World War she carried in excess of 3,000 tons of cryolite from Greenland to Canada on a single voyage when no one was worried about load line certificates. Even on her regular voyages north, her load line markings would be often be submerged on departure from Montreal and later Capt. Smellie admitted he would tell concerned inspectors that Nascopie was just "listing"-- the only ship in the world that could assume an alternating list from one side or the other for the benefit of surveyors.

The Nascopie, in the ordinary course of her annual journeys, was subjected to treatment that would foundered any ordinary ship. New engineers, in fact, wondered at the wicked punishment suffered by the engines until they became familiar with the refinements of her construction and the sturdiness of her engines and rudder post. At first, however, they were resigned to the loss of the propellers and the fracturing of her shaft as the man on the bridge sent her shuddering into a solid wall of ice. 'She was frequently brought to a complete standstill from ten knots and over,' the Captain says. 'That meant a hundred revolutions to nothing in one second. The engineers were scared, but she never suffered. Every piece of crockery on board might be smashed, but her engines and shaft were sound.'

Arctic Command.

Complimenting her Dreadnaught tough hull was supremely reliable and capable machinery-- few ships had better nor put more strains on it. The nature of working in heavy ice, often in effect battering through it, required constant stops and starts and the kind of maneuvering that only a proper set of reciprocating engines can give. Nascopie was powered by a single triple-expansion engine with cylinders of 25½", 35½" and 58" with a stroke of 42" turning a single steel shaft (which was like everything else in the ship, impossibly overbuilt with a 14½" dia. instead of the usual 11⅞") and 6½-ton four-bladed screw turning at 110 rpms. Steam was generated by two single-ended boilers, each measuring 16½ feet in diameter and 12 ft. long, each with three fire boxes, working under Howden's forced draught at 180 psi. Her rated output was 2,500 bhp but she could turn out 2,700 bhp if needed.

|

| Nascopie's engine room detail. Credit: Archives of Manitoba |

Nascopie was, of course, a coal burner and would remain so throughout her long career. There were no bunkering port en route (until the opening of the railway to Churchill in 1930), indeed she carried coal to each of her posts, and had to have 2,500 tons of it for her own needs, burning 20 tons or more a day. Coal had the advantage over oil in in that it could be carried anywhere there was room for it in the ship beyond her nominal bunker capacity and had to be. Nascopie developed a reputation for being rather picky about her coal, preferring Welsh steaming coal and Cape Breton coal was a hit or miss under her boilers. Several times she had to have her entire bunkers changed out when inferior coal burnt out her grates. Many of her ensuing adventures revolved around the burning and the getting of coal on her extended voyages were rebunkering was impossible or uncertain.

Not only did Nascopie have to carry all of her fuel for the round voyage, but with no repair facilities en route, she carried a complete kit of engine spares: "2 top end, 2 bottom end, 2 main bearing, set of coupling bolts, one set feed and bilge valves, bolts and nuts, four propeller blades and mounting, 6 air pump valves, 1 air pump, 4 main feed check valves, 3 piston rings for HP and MP pistons,1 propeller shaft, 1 slide valve and one HP piston valve complete," according to her Lloyd's inspection report.

H.B.S.S. NASCOPIE

Profile & Deck Plan as built

Credit: https://www.gov.mb.ca/chc/archives/_images/ww1blog/2015/2015-06-15_full.jpg

LEFT CLICK on image for full scan.

|

| Nascopie profile and rigging plan (note the schooner rig and sails). |

|

| Nascopie flying bridge & wheelhouse |

|

| Nascopie Saloon Deck (Captain's cabin and Chart Room) |

|

| Nascopie Shelter Deck (officers accommodation aft and passenger accommodation forward) |

|

| Detail of passenger accommodation forward on Shelter Deck. |

As built and for most of her life, Nascopie was not a commercial passenger ship. Indeed, she did not possess a passenger certificate until 1933. As a sealer, 1912-1916 and 1927-1930, she accommodated 250 seal hunters in addition to her normal crew, but they were signed on as crew and on her annual "Outfit" voyages for HBC, she carried company staff and wives, RCMP men and missionaries who were "signed on" as supernumeraries for the voyage.

|

| Nascopie's dining saloon as built. Credit: Archives of Manitoba. |

|

| Nascopie's dining saloon. Credit: Archives of Manitoba. |

|

| The Captain's table in Nascopie's dining saloon, 1938. Credit: Loren Squire photograph, Archives of Manitoba. |

The accommodation for sealers was:"portable beds for them after the style carried in the steerage by all first class passenger boats" and 'tween decks were fitted with steam heating. For her HBC passengers, Nascopie originally had four staterooms forward on Shelter Deck, all outside, and two-berth with an additional settee berth. The dining saloon was adjoining, nicely panelled and used by the officers and passengers. The accommodation was inadequate by 1921 when the house on Saloon Deck was expanded forward and to the sides of the captain's cabin and chartroom to accommodate additional cabins. In 1933 the accommodation was further expanded with cabins built forward on Shelter Deck and she could carry 36 passengers in eight four-berth and four single berth cabins. Her saloon was expanded as well to sit 26 diners per sitting and the old fashioned swivel chairs replaced by free standing ones.

After the majestic liner which had carried us so smoothly across the Atlantic, the Nascopie seemed very small and insignificant. Her decks only just rose above the level of the wharf, whereas the liner had towered up above the dockside. Her paintwork was dark and workmanlike whereas the Duchess had gleamed and dazzled in white. None the less, many of us were, in the years to come, come to form an affection for the little ship which no ocean liner could ever have inspired. Sometimes she was naughty. In rough weather there were few tricks that were beyond her, particularly when coming down the Labrador coast with only a few light bales of furs in her holds. She would then creak and groan in the most alarming manner, but survived the worst hammerings the North Atlantic and the Arctic seas could serve up, to return each year, like a faithful friend, to keep us company for a few hours or a day or so in our northern solitude.

The Last Gentleman Adventurer

The officers and crew, for such a ship, had to be men of iron with an affection for the ship and the North. They were Newfoundlanders, accustomed to hard living, hard tack and diet of fish and potatoes if they could grow them. They liked the good food of the Nascopie, and could afford to rest and fish all winter after their six months back-breaking tour of duty. They slept in ten bunks in the forecastle, with the worst noise in the world a few inches from their heads. In rough weather even the Captain and passengers wedged themselves in blankets on the floor. In good weather, when the ship was driving into the ice and shuddering to a stop, it was a miracle that any man could sleep with his ear against the steel plating which continually cracked into unrelenting ice.

Arctic Command.

Nascopie's compliment consisted of the following (as built):

Deck Dept: Captain, First, Second,Third and Fourth Officers, Bosun, Carpenter, Donkeyman, Greasers (2), Able Bodied Seamen (8)Engine Dept: Chief Engineer, Second and Third Engineers, Firemen and Trimmers (9).Steward Dept: Purser, Chief Steward, Chief Cook, Second Cook, Cook Apprentices (2), Steward, Steward Apprentices (2)Wireless operator

|

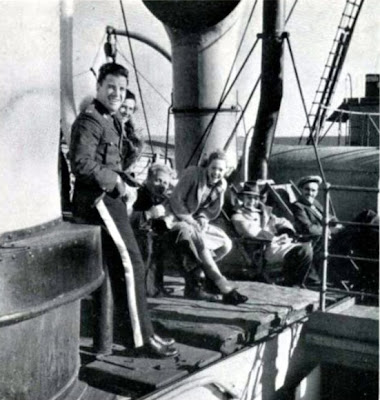

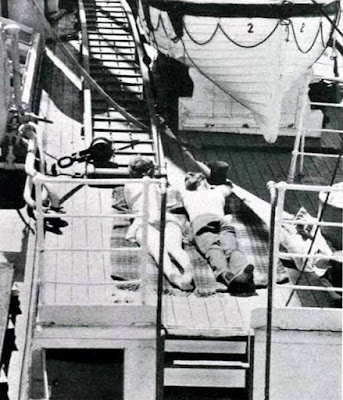

| Some of Nascopie's crew on the 1925 voyage. Credit: G.E. Mack photograph, McCord Stewart Museum. |

A tough ship with a crew to match, no other vessel was better built or manned to take on the toughest climate and conditions any merchantmen would encounter on her regular duties and beyond. H.B.S.S. Nascopie was ready to go to work and embark on a 35-year career like none other.

An interesting expedition will start from the Tyne shortly, when sealing steamer Nascopie will sail for the Labrador coast to engage in the seal hunt. The crew number about 250 men who are specially trained in the work trekking many miles over ice to capture seals. Nascopie is constructed as a powerful icebreaker in the event of becoming icebound.

Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 26 January 1912

Best known for "that" other maiden voyage, the year 1912 would see Nascopie's safely and efficiently accomplished with nary a press mention. Yet it would be the beginning of one of the greatest records of any British merchantman, carrying the Red Ensign to the furthest northern reaches of the Empire and, as Hudson's Bay Co. had done since 1668, forge the Eastern Arctic into the chain of British world commerce and trade. But before True North, Nascopie went seal hunting at "The Front"...

1912

One of Nascopie's best known commanders, Capt. G.H. Mack, was also both a keen photographer and an excellent writer, pursuits which uniquely documented much of Nascopie's career, starting from her earliest days with Mack, then Second Officer, aboard for her delivery voyage which he recounted in the September 1938 issue of The Beaver:

Next January, I joined the Nascopie at Swan Hunter's Yard. Capt. Smith was already there, also the full crew from Newfoundland who were to take her to the seal fishery. My first impression was what a long funnel she had. After looking around, I saw she was a very fine ship indeed; and, thank goodness, she had wooden laid above her iron decks-- a blessing among the ice and snow when the iron decks get too slippery for safety.

We left the Tyne one afternoon, and started down the North Sea. Captain Smith was ill with a bad cold. We were bound for Penarth in the Bristol Channel to bunker with Welsh coal for the seal fishery.

The Nascopie steamed well, and we went down the North Sea in great shape. The crew had considerable trouble with steering with the steam steering gear. They had been used to steering schooners and the hand gear of the old wooden sealers. Their style was 'hard up and hard down and steady.' When we arrived off the Newarp and Cross and Light ships, the traffic was very heavy. We just met the colliers bound north from the Thames and we swung and yawed like a drunken man. We passed the Newarp amidst a blowing of whistles from indignant collier skippers who were quite sure on which side we meant to pass. It looked at one time as if we were going to ram here. I tried my hardest to explain we were not in the ice pack, and to give her as little helm as possible. A mere second mate had to use diplomacy with that crew, who were all skippers and captains among themselves.

Passing Dover we nearly rammed one of the Cross Channel boats which had just left the harbour. Captain Smith's cold was worse, and he kept to his bunk.

We picked up the pilot off the Nash lighthouse, and duly docked at Penarth Dock. The doctor I got said Captain Smith had pleurisy. Captain Wayte took charge of the ship, and I took Captain Smith across England to Lincolnshire to his home at Eagle Vicararge.

The Beaver October 1938

Nascopie left the Tyne on 25 January 1912, immediately after trials, bound for Penarth, Wales, where she took aboard 1,500 tons of coal for St. John's and also the shipwrecked crew of the Newfoundland brig Bella Rosa which was lost in mid ocean the previous year.

Departing Penarth the morning of 7 February 1912, Nascopie was expected at St. John's on the 13th but on the 17th had still not arrived, the Evening Telegram that day reporting that "the offing is full of the heaviest kind of slob ice and no steamer of the ordinary kind can penetrate it, as it land locked, inside the Cape is rafting on the shore and offers an insurpassable barrier to shipping either coming or going from port. The Nascopie will likely negotiate it, but it will take her some time to do so."

|

| Credit: Evening Telegraph, 19 February 1912. |

Nascopie finally came into St. John's the evening of 18 February 1912, and the next day's Evening Telegraph wrote that "To-day crowds flocked to Job. Bros. premises and inspected the new Dreadnought, Nascopie. Her tonnage is 1870 gross, 1004 nett and she carries 2600 tons deadweight. She has triple expansion engines and her builders turned out the mammoth ships Mauretania and Lusitania [sic]."

|

| Credit: Evening Telegraph, 19 February 1912. |

The delivery trip was as arduous and testing enough as could be desired of a vessel that was designed and built tough and was proven on her very first voyage. The Evening Telegraph described the voyage in admiring detail:

Messrs. Job Bros. & Co.'s new sealer Nascopie, Capt. Waite, steamed into port shortly after 7 p.m. yesterday, after a voyage of 11 days from Penarth, Wales. She left there on Wednesday week, the 7th inst., and on the run out had very stormy weather all through and this tested the ship's qualities as a sea boat. She was more than up to expectations in this respect. Gales raged continuously from S.S.W. veering to N.W.. with a heavy sea but no special incident occurred. About 300 miles due east of St. John's, before the vessel came to the edge of the Banks, and the ship's qualities as an ice breaker were tested in butting and forcing her way through the heavy floes which covered the ocean. The floe consisted of the heaviest kind of slob which was rafted in some cases, the ship, however, with her superior speed and ice breaking qualifications bored her way through it, and Wednesday last at noon, as reported by a Marconigram transmitted by the Cunarder Carmania. Was 526 miles east of St. John's, and 200 miles off at 10 a.m. Friday, so that she progressed at the rate of 7 knots an hour in coming along and covering the distance of 326 miles. She would have made a fine run to port but for meeting so much ice. Saturday at 5 p.m. Motion Head, Petty Harbor, was sighted and shortly after as a thick snow storm raged the ship bore away to the E. by S. to avoid the coast which now could not be discerned owing to the storm. Yesterday morning at 8 o'clock the ship was again headed for the shore and by 11 a.m. she was off Red Head, near Torbay. At 5 p.m. after forcing her way up through the slob she was headed for the Narrows. Here the slob was rafted on the shore and several feet thick, and the ship had her work cut out for her. After an hour's hard butting she got a lead off the North Head and came full speed through the Narrows. The weather having momentarily cleared and she later berthed at the owner's piers. Capt. Waite was on the bridge from 4 a.m. yesterday until port was reached and was pretty well used up.

It was added that "The ship is speedy boat and several days rolled off 240 miles, her lowest run being 128 knots." One of Nascopie's passengers was Capt. Jas. Joy who was returning from Tyne after supervising the construction of the ship.

Nascopie was moved on 20 February 1912 to A. J. Harvey & Co. south premises to discharge her 1,500 tons of coal. On the 24th Nascopie made her first visit to Canada when she left St. John's for Louisbourg, Sydney, NS, to load coal for Job's sealing fleet and also had three passengers for the voyage. When she sailed from Louisbourg on the 28th, she had 15 passengers and 200 bags of mail, "she should arrive here to-morrow evening as she is a very powerful boat and will get through the ice which is now on the coast." (Evening Telegraph, 1 March 1912). Nascopie arrived at St. John's at 10:00 a.m. on the 3rd, "and made a fine run down to Cape Race. When in that vicinity heavy slob ice was met, but did not retard the progress of the ship." She brought 2,500 tons of coal, 200 bags of mail and eight passengers.

|

| Credit: Evening Telegraph, 6 March 1912. |

Nascopie was now made ready for the seal trade. Sealing was a brutal, bloody business, not for the faint of heart ashore or afloat, hazardous in its pursuit and subject to the vageries of weather, ice and luck in the amount of success and profit it gave to the tough men who pursued it. Sealing ships, their paintwork worn off by the ice, streaked with frozen salt spray and coal ash strewn on their icy, bloody decks covered with planks to give some footing to the spiked boots of their crews, looked as bad as they smelled and it was grim first employment for a brand new vessel.

Indicative of the rigours of sealing "at the front," even the staunchly-constructed Nascopie had 2 ft. square "ice beams" fitted athwart her open holds as further strengthening. Instead of a crew of 46, she went sealing with 275, almost all seal hunters, who were accommodated in portable steerage like open berths in her 'tween decks. She had galley facilities built in her forward 'tween deck for the purpose. Planks were fitted over her teak decks to protect them from the spiked ice boots and bloody seals. She also took aboard extra lifeboats and cutters.

New, too, to the ship were her captain and crew. So specialised was the sealing trade that Nascopie, except for her engine room officers and firemen, changed her entire crew to one signed on locally by Job Bros. including the captain. Seal captains were a breed apart from high sea commanders, driving their ships hard into the ice packs of the Labrador Front, often "in the barrel" (as the crow's nest was called) spotting seal packs on the ice flows, and the finesse of navigation and ship handling played a secondary role. Indeed, on her sealing voyage, Nascopie only carried one deck officer in addition to the captain. During her pre-war sealing years (1912-15), she was commanded by one of the legendary skippers in the trade, Capt. Geo. Barbour.

|

| Capt. Geo. Barbour. Credit: Newfoundland Quarterly, July 1914. |

The late winter/early spring of 1912 produced an exceptional amount of ice and St. John's, quite exceptionally, was ice-bound by early March and Nascopie and Bruce were the last enter to leave the harbour on 2 March and later inbound steamers had to put into Bay Bullis and been icebound for days.

Conditions improved to permit the sailing of that season's sealing fleet from St. John's on 14 March 1912 with Bellaventure, Bonaventure, Florizel, Adventure, Nascopie and Beothic sighted in order passing Cap Bonaventure.

It proved to be a difficult first sealing season for Nascopie and on 15 March 1912 she wirelessed that she had lost three of the four blades of her propeller and the remaining one had lost two feet, after hitting submerged ice. "All crew shifting cargo to bring boss out of water if possible. Good sign of seals, judging about 15 or 20 miles off. Very sorry, anxious time, nobody to blame. Ship carefully handled, Boethic and company gone on for the patch."

Nascopie carried a spare propeller blades for such eventualities By flooding the forward hold, her stern was raised up and the screw boss exposed and using the ice floes which surrounded her as floating platforms on which to work, the replacement blades were bolted to the boss. On 18 March 1912, she wired that three blades had been replaced and reshifting cargo and would be underway by noon. It was a remarkable example of resourceful and skillfull work on the part of her Chief Engineer James Ledingham and his small crew.

Mr. Ledingham proved as adept as recounteur as he did an engineer and like Capt. Mack, contributed extensively to The Beaver with accounts of the early days of the vessel including this account of her days sealing accompanied by his own photographs in the March 1925 issue:

The annual seal hunt from St. Johns takes place each year during the months of March and April. Early in March the ship is being made ready.

The decks are covered over with one-inch boards first. As the sealers wear boots the soles of which are studded with spikes to prevent slipping whilst on the ice, these boards are to prevent the permanent wood decks being cut up by the spikes. Bunks to hold some 250 men are built in the ‘tween-decks, the full complement of men on board being 270. Extra store-rooms are also built. For the use of the men solely a large cooking galley was built into the ship during her construction.

About forty extra boats are taken on board, and many rope ladders to assist the men climbing up and down the ship’s sides, also coils of small ropes to be cut up into suitable lengths and used by the men as hauling lines when hauling a tow of 'fat' to the ship. Each man is provided with a gaff to help him over the ice.

All the sealers are shipped on a share basis. If the trip is successful, a man’s share may be $100, and—no seals, no money. The owners advance each man an equipment, which is deducted from wages when paying off.

By March 12th all is in readiness, and on sailing day, which is March 13th, some twenty ships are moving out of the harbour amidst much excitement and blowing of whistles, each ship trying to make more noise than her neighbour. After getting outside the narrows we steam along in open water with a full head of steam, racing madly down the shore, jockeying with each other to get the lead.

Ice is next encountered, when the big ships have the advantage of being able to force their way through the pack. ‘The smaller ships try to keep in the 'wake'’ or else follow the “‘leads’’ or cracks in the ice.

Perhaps, after a day’s steaming, the first 'whitecoat,' as the young seal is called, is sighted. A sealer scrambles over the side, clubs the young seal and hauls it on board. It is taken to the captain (an experienced seal killer) and his officers. Discussion takes place as to whether this particular seal is one of the northern or southern patch of seals. After judgment is given, the tail is cut off and hung up in the saloon and success to the voyage is drunk in the usual time-honoured way. Then the ship is headed where it is thought the seals are likely to be. A good look-out is kept from the masthead and perhaps soon the cry of 'seals ahead!' is heard. Every man gets his line, knife and gaff ready and is just waiting for the order 'all hands overboard' Killing commences as once. Men drag their seals to a pan of ice, and when there are a hundred or more on it a flag is put up showing the ship’s recognized number or initial. Then another pan is made up and flagged, until for miles the ice-field may be dotted with flags.

The ship follows the men and picks up the seals on each pan in rotation. When night begins to come on, the pans have lights put on them to facilitate picking up after dark. It is often necessary to use the searchlight at night-time picking up.

About midnight the ship is stopped; the men try to snatch what sleep they can and also stow the seals on deck during the night watches. Up before day-break next morning, the same procedure is gone through until that particular patch of seals is cleaned up. Then away to hunt for another patch! If the seals are plentiful and not scattered too much, the ship may pick up a good catch in a few weeks or less.

If the young seals are not struck within a few weeks of their birth, they take to the water, when it is almost hopeless to get a load, as they have then to be shot. A young seal in a few weeks averages about fifty pounds in weight.

When a good patch of seals is struck, only enough men remain on board to work the ship along. Often I have seen the captain in the look-out at the masthead, the doctor at the wheel and chief engineer on the bridge. The cooks are generally on board and, in the midst of getting meals ready, they have to jump on the ice, ‘strap on' and drive winches. The doctor is sometimes kept very busy bandaging wounds, as most men happen to cut their hands when skinning seals, and the cuts, if not attended to, develop into nasty sores.

The fat of the young whitecoat makes the purest oil, so that it is the ambition of every ship’s crew to get as many young as possible. If a family of seals happens to be together when a sealer approaches, the 'old man' will slide into the water immediately, but the mother will stay and defend her young, often attacking and tearing a man’s clothes.

Arriving back at St. Johns, discharging takes place immediately. The skins are laid out in the sheds, the fat cut off and sent away to the culling machinery, then passed on to the vats to be rendered down. There are steam vats and sun vats. The sun vats make the purest oil, almost as clear as a glass of water.

They are generally a happy crowd, the Newfoundland sealers, playing all kinds of pranks on one another. They are very strict in their observance of Sundays at sea; I have seen the ship stopped at midnight Saturday and not started again till midnight Sunday.

Very often serious accidents occur, when ships and men pay the penalty—the wooden ships getting crushed in the ice; men getting astray the ice in snowstorms. Only a few years ago some forty men lost their lives in this way. Another ship, homeward bound, with a full load, disappeared without leaving any trace. The Nascopie herself did not come scot-free. One day, amidst the ice, the four blades were stripped from her propeller. After three days’ strenuous work, new ones were put on by the engineers and the ship managed to get a paying load.

Stowaways are always at the seal fishing, sometimes boys just beginning their teens, and when put to work take themselves very seriously. One lad, while the ship was homeward bound, happened to be down in the stokehold when the mate sent for him to come and polish brass-work. Quick as lightning came his answer: ‘You go and tell the mate polishing brass-work won’t get the ship along. I’m firing.'

It’s not always possible for even the powerful ships to force a passage through the ice, especially if fishing within sight of land with a strong in- shore wind and the ice jammed and rafted up. In company with three other steel ships, the Nascopie was held fast for sixteen days. The weather vas generally fine and the men played all kinds of games, even to pitching buttons. Mock trials are held and suitable punishment given to the unlucky offenders.

All the ships are fitted with wireless and keep tm touch with the coast stations. Lately an aeroplane has been added, and it takes a flight out over the ice to try to locate the seals, when it transmits the news to the ships.

By the end of April the last sealer is generally in and the seal fishing is over for another year.

Back on the hunt, Nascopie reported she had 6,000 seals to her credit by 22 March 1912, but on 2 April in the Belle Isle Straits, she lost another propeller blade and with the ice breaking up and stormy weather, Capt. Barbour decided to bring her home and she arrived at St. John's early on the 5th. When she finished discharging, her catch totalled 17,057 seals, the gross value being $36,000 and on the 9th her sealing screw of 270 was paid off, each receiving $43.71; "it was indeed gratifying, as the owners remarked, to see the men make such a bill considering that the ship was crippled at the early stage of the voyage" (Evening Telegram, 10 April 1912). Capt. Barbour's share of the voyage amounted to $1,421.60.

During the hunt, instead of the nice clean cargo of supplies for the Company posts, she became full of seal, hides, meat and guts. The ship became a smelly mess, and it took a thorough cleaning job with caustic soda to make her fit again for her northern voyage.

R.M.S. Nascopie, Ship of the North

Nascopie was not to remain spruce for too long and Jobs then put her to work carrying coal from Sydney, Nova Scotia, leaving there on 24 April 1912 for Botwood (north Newfoundland) where she arrived on the 29th. On 16 May she was reported at Placentia Bay discharging another cargo of coal from Sydney and on the 23rd at St. John (NB) also with coal.

|

| Capt. A.C. Smith who commanded Nascopie on her first trip north for HBC and again in 1914. Credit: Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia |

Her collier duties completed, Nascopie arrived at St. John's on 13 June 1912. During her discharging, she got a new captain for her first Hudson Bay season, Capt. A.C. Smith, formerly in command of Pelican, who arrived from England to succeed Capt. Waite who went on the Beothic. On the 19th, Nascopie underwent her first drydocking and overhaul in preparation for sailing for Montreal whence she would undertake her voyage north on account of Hudson Bay Co. through September. This included a complete repainting and her Job. Bros. houseflags on her funnel were overpainted in buff when sailing for HBC.

Meanwhile, Second Officer G.H. Mack and some of the regular crew of Pelican including the boatswain and cook, left Liverpool in Allan Line's Pomeranian in May 1912 for St. John's to join Nascopie on her upcoming HBC voyage north, as he recounted years later in The Beaver, September 1938:

Arrived at St. John's, we found the Nascopie off to North Sydney for a cargo of coal. On her return, there was plenty of cleaning to do. The ice beams were put in again: these were twelve by twelve-inch pitch pine logs squared off right across the ship, in case of heavy ice dam. The ship still smelled of blubber from the seal fishing, and we had many arguments as to whether this would affect the food. However, the ship was scrubbed out with strong caustic soda by Job Brothers' shore gang.

The crew were signed on; the engine room and stewarding staff came from Newfoundland, except the cook, who had come over with use from the Pelican.

We left St. John's with many people to see us off. A voyage north in those days was still an event, and this was the Nascopie's first trip.

The trip to Montreal was uneventful; fog as usual rounding Cape Race, but it cleared up at Cape Ray. It was evening when we reached there, and the Nascopie finally let go and we had a splendid passage up to Fame Point and on to Montreal.

|

| Nascopie at Montreal. Credit: Flickr, Donald Gorham. |

Nascopie arrived at Montreal on 3 July 1912 and began loading for her maiden voyage "Up North" and sailed on 2 August. Second Officer G.H. Mask recorded in detail this important first trip, one of the 33 Nascopie would undertake, for The Beaver, September 1938:

The passengers started to arrive. Among them were the Fur Trade Commissioner, Mr. Hall, his daughter and sister, and with them, Captain Freakley. Ralph Parsons was returning to the Hudson Strait district, just being opened up. Mr. & Mrs. C.T. Sheppard were going to Wolstenholme. Two apprentice clerks, Chalmers and Mitchell, were destined for the Strait and York Factory. Two priests were off for Chesterfield Inlet to build a mission there. Fathers Turquetil and LeBlanc and Rev. J. Bilby were bound for Lake Harbour, Baffin Land.

|

| Some of Nascopie's passengers on her first voyage North. Credit: Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia |

This was the first time all the goods for the Bay had gone up in one ship. Large as the Nascopie was, we had a very full load and a tremendous deck cargo.

After we left Father Point and dropped the pilot, we ran into fog which continued right through the Straits of Belle Isle and last up to the South Wolf Islands. There were plenty of bergs about-- not nice travelling.

We call at Cartwright and Rigolet. We had fine clear weather on the coast, and the Nascopie made good time. Leaving Cartwright for Rigolet, we went round by the Dog Rocks and inside the Puppy Reef through Packs Harbour and the Horsechaps, Tub Harbour, then into Hamilton Inlet and thence to Rigolet. From there, along the northern shore of Hamilton Inlet, through Cut Throat Tickle and north to Davis Inlet, we had fog and many bergs.

We had plenty of fog after leaving Davis Inlet, and had to go slow because of bergs. The Fur Trade Commission got impatient about this, and reminded us the ship did 14.2 on her trials. I explained that dodging bergs at full speed was unwise, as witness the Titanic affair which had happened earlier that spring. Luckily in the midst of one of these conversations, we just missed ramming a berg.

|

| Map showing the route and itinerary of Nascopie on her first HBC voyage, August-October 1912. Credit: The Beaver, September 1938. |

The passengers had much amusement except reading and playing cards. The food was pretty good, and the big ice box supplied plenty of fresh meat.

There was not much ice at the entrance to Hudson Straits. What little there was, the Nascopie walked through.

Crossing to Lake Harbour, the pilot Navolia was picked up off Beacon Isle, and we went up the run through the Narrows to the post. Here S. Sainsbury, who had been wintering with the Church of England missionary, Mr. Broughton, came off. He told us Broughton had been frozen [frostbite] during the winter, and was in bad shape. In those days we had doctor aboard. I went ashore to the Mission with Captain Freakley and Rev. Mr. Bilby. Broughton had been badly frozen indeed. Captain Freakley did what he could do to make comfortable, we could do little without a doctor. Medicines and books there were in plenty, but no surgical skill. After the cargo had been landed, we took Broughton aboard with Sainsbury to help look after him. Rev. Mr Bilby remained to attend to the Lake Harbour Mission. It was decided to take Broughton to the C.G.S. Minto, surveying in Nelson Roads for the terminals of the Hudson Bay Railway then planned for Nelson. At Wolstenholme, Mr. and Mrs. Sheppard were landed, and we picked up Robert Flaherty, who was prospecting for Mackenzie and Mann. He had gone from Great Whale River across country to Fort Chimo in the winter. Leaving Chimo after the break-up, with four Eskimos, he went up the western shore of Ungava Bay as far as Leaf River, up Leaf and across the Ungave Pensinsula out into Hudson Bay, up the Bay coast to Cape Wolstenholme, around it, and then into the post in Erik Cove-- quite a trip when you come to think of it. The four Eskimos and Flaherty's canoe were also taken on board.

Churchill and Chesterfield Inlet were the next ports of all. Chesterfield had been established the year before by the Pelican, and we were anxious to learn how they got on during the winter. It had been the same at Lake Harbour. We had speculated too as to whether Navolio would take the Nascopie, a much bigger ship than the Pelican. Navolio never turned a hair not batted an eyelash, but was calm and cool. When it comes to pilots, Navolio is in the same class as old Partridge was for the Koksoak River going up to Chimo-- a pretty high class. To appreciate this, one see these places low, especially the Koksoak River.

We towed a coast boat from Churchill to Chesterfield, one that had come down from Chesterfield earlier in the summer. When we reached Chesterfield, we saw with pride the two buildings the Pelican had erected the previous year. Everything was well, and it had been a good year for fur. It was hard work landing supplies, and those for the new mission had been land in a different place from the post supplies. The post had a particularly bad beach. Humping cargo on your back, in water up to the waist, was cold work till you got used to it. The Nascopie searchlight made a vast improvement on the Pelican.

The new mission was to be one building, church and house combined. Plenty of natives had congregated, so there was lots of assistance. Most of them had been some time with Scottish and American whalers. Some had a smattering of English and well know names like Billy Bedamned, John S. Sullivan, and others not so respectable. They wanted to hold a dance but we didn't have time.

Leaving Chesterfield Inlet, we ran into a very heavy north-easterly gale with a nasty sea about on our port beam. The sea was made worse by strong tides running. The Nascopie, having no bilge keels in those days and being a bit light, showed us exactly what she could do in the way of rolling. Furniture shot out and spread clothes on the deck. Pantry and galley were a continual clash of crockery, mingled with curses and tragic appeals to heaven from the cooks and stewards. Hearing a great uproar in the saloon about two one morning, I went down. The large upright medicine chest had been torn from its moorings and crashed over. Medicines, pills and what-nots were all over the floor in one gorgeous mixture, enough to cure and poison a regiment.

We arrived in York Roads, and got in touch by wireless with the Minto, which was surveying off the Nelson Shoal. We hove up again and went poking about that hell-hole looking for her. That afternoon, Broughton was put aboard under the Minto doctor's care, also our fourth engineer, who was very ill. That night just before dark we steamed back to York Roads and anchored.

The Fur Trade Commissioner and his party, with Captain Freakley, left us at York to up the Hayes River by canoe and out to Winnipeg. Eventually, we finished unloading in York Roads, and then loaded the returns. Couch and Shanks came out with us, their two years being finished. We left for Charlton Island. We went into Charlton Sound by going round the Lisbon Rock, and anchored outside the Bar. Miller, the pilot, came out to take us in.

This was Miller's field day. He lived on Charlton Island all winter looking after the depot, and had his wife and family with him. When be came out as pilot for a few hours Miller was boss. He was a marvel, and could handle a ship well under either steam or square-rigged sail.

We went over the Bar with two leadsmen working, and Miller exceedingly businesslike. He could dame the man at the wheel as well as any London river pilot. We went gingerly alongside the wharf, a very rickety affair which fitted at No. 2 hatch and had a home-made railway running along it.

The Nascopie was the longest ship that had ever been there, and we had a job mooring her astern. Wires to the wreck of the Sorine helped. (It was a treat to be alongside again. After work we could walk, and we trout-fishing one Sunday. We used a whiskey-jack for bait until we got trouts' eyes.) One day when I was helping sling cargo down No. 2 hold, I heard a tremendous cracking and general uproar on deck. We climbed out of the hold in time to see the last stern wire parting, a couple of deadmen being torn out by the roots. The strong spring tide had caught the Nascopie's stern and the moorings could not stand the strain. The wharf gave a tremendous heave and collapsed, and the Nascopie swung to her anchor in midstream.

|

| This is what Nascopie did to the wharf at Charlton Island on her first call. Credit: G.E. Mack photograph, McCord Stewart Museum. |

This meant a lot of extra work. The shore gang under Miller re-erected the wharf-- a highly technical operation, but somehow they accomplished it. I had a gang putting down extra deadmen and anchors for the stern moorings for a couple of days. Then we got back to the wharf again.

When we left Charlton, we took on board Mr. Hooker and his wife and family, bound for Fort Chimo. Robert Flaherty left to out by canoe to Cochrane from Moose Factory. We would miss his entertainment in the evenings.

Any fears about the Foxe Channel ice being down were groundless. There was none in sight. Snow was on the hills at Wolstenholme, and the weather was getting colder. George Ford came aboard at Wolstenholme, and we said goodbye to the Sheppards, who were to remain for the winter. A quick trip to the mouth of the Koksoak Rivver. The four natives who had gone to Wolstenholme with Flahery belonged to Chimo: Nikki and Ambrose and Jimmy Partridge, son of old Partridge, the pilot.

When we arrived off the river the tide was exactly right. We had the other natives aboard, so Captain Smith decided not to wait for Partridge but to go on up to Chimo. Crossing the outer bar, we saw poor old Partridge making great efforts to get to the ship. The tide was then running, and we were steaming for all we were worth.

To appreciate going up the twenty-five miles from the mouth of the river to the post, one must do it. The rise and fall of the tide is over forty feet, and there are three bars to get over. The sides of the Narrows are steep. The ship is literally hurled through with the incoming tide, besides going as hard as it can steam, for a time seems to charging downhill.

We reached the post safely, and anchored. The post manager came out, and said we were anchored in the wrong place by the inside buoy. No other buoys were visible. He explained this was because the moorings of the other buoys were too short; they would be visible when the tide went down. Captain Smith's language was a joy. We sounded round, and remoored the ship in the right place.

On the last of the flood, Partridge arrived, a hurt and crestfallen man. After years of piloting the Erik and the Pelican, and perhaps the Labrador, he had been done out of the first piloting of the big new ship.

We did not go to the George River after leaving Fort Chimo, as their returns were brought around in the local schooner Fox. A dance was held ashore, attended by both Hudson's Bay Company and Revillon Freres men. Working your way through one of those evenings without missing a dance was hard work. In closely packed room were many wore native dress and seal skin boots, the air was thick.

From Chimo we left for the Labrador posts. We called at Rigolet and Cartwright. At Rigolet we had the usual goose feed in the clerk's quarters. This was the house where Lord Strathcona had lived.

We arrived in St. John's, and the first voyage of the Nascopie was over.