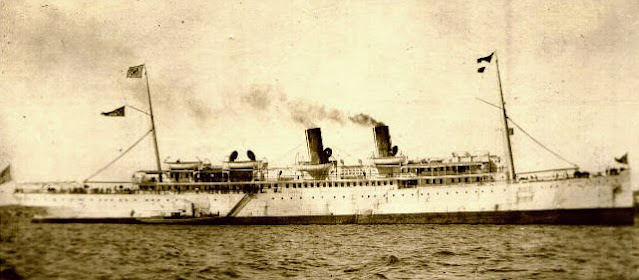

Men who for many years have been meeting the notable liners Sonoma, Ventura and Sierra, formerly in the Spreckels' Oceanic Steamship service, which two years ago passed to the Matson Line, aver that these ships each sail under a lucky star.

Old-time sailormen on these boats, with assurance born of superstition, which more or less engenders into their lives, that the grand old ships are blessed by the Southern Cross under the influence of which they pass to and from the Northern and Southern hemisphere in their journey from San Francisco to Sydney.

San Francisco Examiner, 10 March 1928

If ships have minds-- and any sailor who had wrestled to keep a cranky Hilonian on course or nursed the sick boilers of a Hawkeye State will swear they not only have minds but malevolence to spare-- then the creaking old Ventura must have gone smiling to the ironmongers. Inexpertly designed, repeatedly repaired, remodelled, and patched up, she plowed the South Pacific for thirty years with her sisters, Sierra and Sonoma, at first the best in business and at the last sad, outmoded, outspeeded, and mostly ignored by shippers and passenger alike.

Cargoes: Matson's First Century in the Pacific, William L. Worden.

Over a three-decade period they... as a trio, then a pair and a threesome again... first with two funnels, then but one, held down U.S. Ocean Mail Route No. 75 San Francisco-Antipodes. Conceived with the unbounded confidence of The Gilded Age, they arrived with the dawn of a new century which saw America emerge as a Pacific power. Late in delivery, flawed in design and fittings, they matured into stalwarts of the U.S. Merchant Marine through good times and bad, government encouragement and indifference, the vagaries of trade and travel patterns, war and peace. They figured, too, in the history of Australia and New Zealand from originating the now legendary paper streamer "farewelling" tradition to returning the triumphant All Blacks after their first overseas tour. No trio of liners served longer on the same route than U.S.M.S. Sierra, Sonoma and Ventura which between them put in a good six and a half million ocean miles beneath the Stars & Stripes and the U.S. Mail flag.

|

| Three decades later, U.S.M.S. Ventura at Sydney. Credit: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 5-2723 |

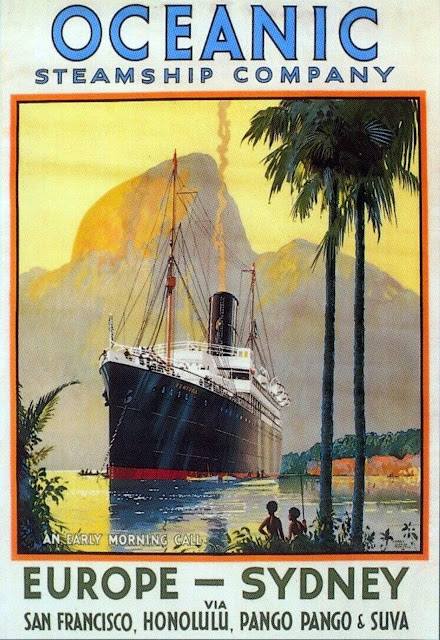

Get up and get away! The Oceanic Steamship offers you the opportunity. Go and learn what the other half of humanity is doing and how it lives. It will “pay,” as we Americans say.

The Oceanic Steamship Company is an American line, sailing under American register and the American Flag, its ships having been built in American ship-yards, namely Cramp's in Philadelphia, is engaged in building up the traffic, both freight and passenger, between the United States and various islands and countries in the Pacific, namely, Hawaii, Samoa, New Zealand, Australia, and the Island of Tahiti.

International Railway Journal, May 1904

It was one of the oldest and the most enduring American-flag trans-ocean route as well as the longest. From 1885-1977 with a few lapses and gaps, the Oceanic Steamship Co. and successors maintained a passenger, mail and cargo service from Golden Gate to Sydney Heads. Known variously as The Oceanic, The Spreckels Line, the A. & A. (American & Australian), The Sydney Short Line, Matson-Oceanic and Pacific Far East Line, from the first voyage of Alameda in November 1885 to the last San Francisco homecoming by Mariposa (III) in April 1978, it is the story of success and struggle and of American ships and seafaring along 7,500-miles of ocean highway in the South Seas as rich and varied as any in the annals of the U.S. merchant service. They came to be known as "The Yankee Mailboats" Down Under and no moniker was as proud or more deserved.

In an uniquely American beginning to the oldest of all U.S.-flag shipping companies-- a confluence of one of the most famous and successful magnates and empire builders, a German immigrant named Claus Spreckels, and an obscure Swedish immigrant seafarer, Capt.William Matson-- two shipping enterprises both began services in 1882 linking Hawaii and later the islands of the South Pacific and the Antipodes with the boundless and buoyant America of the Gilded Age.

One of America's great merchant adventurers, empire builders and developers… of communities, industry and commerce... Claus Spreckels (1828-1908) was the quintessential American success story. In 1846, he emigrated from Germany to America, first New York City and then San Francisco and from running a grocery store to a brewery to resorts and sugar beet refineries. By 1876 he set his entrepreneur vigor upon the Kingdom of Hawaii which had signed a Reciprocity Treaty with the United States the previous year, removing duty on sugar imports and opening up commerce between the two. In 1878 Spreckels founded Spreckelsville, a company town on Maui which became the largest sugarcane producer in the world.

|

| A Dynasty of Destiny: Claus Spreckels (1828-1908) (left) and his son John D. Spreckels (1853-1926). |

Matching his father in business acumen, the eldest of Claus Spreckels' five children, John D. Spreckels (1853-1926), started J.D. Spreckels & Bros. in 1880 which concerned itself with the refining, transport and distribution of Hawaiian sugar. With shipping services from Hawaii to California wholly inadequate, the Spreckels set their sights on starting their own line. On 23 December 1881 the Oceanic Steamship Co. was incorporated in San Francisco with a capital stock of $2.5 mn. and began regular San Francisco sailings with the chartered British steamer Suez in June 1882.

There was business enough to share with a Capt. William Matson (1849-1917) who was a Swedish emigrant seafarer and captain of Spreckel's yacht Lurline. The two established a friendship and Spreckels bought shares to finance Matson's first vessel in 1882, the 195-ton schooner Emma Claudina, named after Spreckel's daughter, which made her first voyage under the Oceanic houseflag in April. Thereafter, Oceanic and Matson cooperated fully and came to dominate the island trade.

|

| Mariposa and Alameda, Oceanic's first new ships of 1883, established a tradition of longevity for the line's ships unmatched in the U.S. Merchant Marine. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

Spreckels lost little time in ordering its own tonnage and in 1883 two new steamers, the 3,158-grt, 14-knot Mariposa and Alameda were delivered by Wm. Cramp of Philadelphia. After making their epic delivery voyages from Philadelphia to San Francisco, around Cape Horn, in record times (46 days), they made their maiden voyages to Honolulu on 25 July and 22 September respectively. They went on to be among the most enduring and successful of all American passenger vessels, indeed setting a tradition of longevity that would characterize no fewer than four generations of Oceanic liners. Reliable, fast and more comfortable than anything yet seen on the South Pacific, Alameda and Mariposa were instantly popular and opened up a new era in travel to and from Hawaii, long before Matson operated passenger steamers and indeed in advance of Hawaii as a popular tourist destination.

Far wider horizons beckoned when, in 1885 Pacific Mail Steamship Co. relinquished its Australian mail contract which Oceanic together with the Union Steamship Co. of New Zealand now shared, securing a three-year contract with both Australia and New Zealand for a four-weekly service from San Francisco, Honolulu, Pago Pago, Auckland and Sydney, effective in November. Towards, this New Zealand paid $100,000, New South Wales $50,000 and the United Stated, $20,000 per annum. Alameda and Mariposa were assigned to this with Union contributing Mararoa (1885/2,598 grt). Alameda undertook the first sailing of the new service from San Francisco on 23 November 1885 to the Antipodes.

In February 1886, Oceanic bought Australia and Zealandia from Pacific Mail and put them on the direct Honolulu run and they were uniquely registered in Hawaii, retaining their names.

The first meaningful American encouragement of its overseas shipping, the Ocean Mail Act of 3 March 1891 came in the nick of time after John D. Spreckels threatened to end the Oceanic service unless there was a substantial increase in subvention by the U.S. Government to support the route, already a sore point with the governments of Australia and New Zealand whose contribution towards it were far higher. Under the Act, Oceanic was paid $2 per ocean mile for outbound sailings. For the rest of the company's existence, however, Oceanic's fate and relative fortunes were dependent on mail contracts on what had already proved to be a marginally profitable enterprise. For its part, Union S.S. Co. placed the new 3,915-grt Moana, its largest steamer, on the route in 1897 and the combined service reached a pinnacle of popularity and efficiency.

What had, hitherto, been the efforts of private business modestly encouraged by government, to further American interests in the Pacific would now give way to national purpose and power at the dawn of a New Century.

Mr. J.D. Spreckels has given a substantial guarantee for the future in the steamships he has placed on the route, and by substituting the existing three-weekly for the former monthly service. These high-class liners are over 6,000 tons each, nearly double the tonnage of the ships which did their work up to the end of 1900. They have a guaranteed speed of 17 knots. They perform their portion of the journey from Sydney to London, by way of America, in such time that travellers may find themselves in London in about 31 days after leaving Circular Quay. These are entirely new ships, having been built expressly for the A. and A. Line at a coast of over half a million sterling… As Mr. Spreckels puts it, the Company is determine to make the fit for its opportunities and 'we have got the desired steamers.' They have necessitated a large expenditure, but the directors do not begrudge it.

Oceanic A. & A. Line brochure, c. 1904

1899

In the wake of the Spanish-American War, America suddenly embraced her navy and merchant marine, the later having entered a long decline that predated the Civil War. The Age of Steam not only relegated the storied American tea clippers to oblivion but was harnessed by locomotive not steamships to open up the expanses not of oceans, but of the great American West. The trans-continental railroad and the Panama Canal were bookends to America's remarkable Gilded Age, both accomplished by the national government and traditional Whig Republican policies. Yet the connecting shipping lanes to compliment them lagged with no meaningful government encouragement of the U.S. merchant marine since the 1891 Ocean Mail Act. Such was the decline, that Oceanic Steamship Co. was one of but a handful of American overseas lines still in business along with American Line, Pacific Mail and Red D Line. The United States was suddenly an ocean empire with neither the sufficient navy or merchant marine to maintain it.

In the space of three months in 1898 the United States of America became a Pacific power and cobbled together, by war with Spain, treaty with Germany in Samoa and a bit of guile and chicanery with the Kingdom of Hawaii. The Battle of Manila Bay took but the morning of 1 May but the ensuing annexation of what Oceanic still referred to in some of its brochures as the Sandwich Islands was both more peaceful and gradual. President McKinley announced the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands on 7 July which would see Hawaii became a fully fledged Territory of the United States on 14 June 1900. What Spreckels and other American businessmen had wedded to the United States commercially was now joined to it politically.

|

| From an Oceanic brochure c. 1890s: "The Sandwich Islands" were no longer just the heart of Spreckels' Sugar Empire but now America's first Pacific Territory. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

For the United States and for Oceanic, it was a New Century that saw the power, prestige and commerce of the country reoriented to the expanses of the Pacific, both North and South, and extend to the British Dominions of the Antipodes which were closer to U.S. West Coast than they were to the Mother Country. That and the growing popularity of the "American & Australian" route via America to Australia and New Zealand promised expanded cargo, mail and passenger trade.

Moreover, Hawaii as an American territory meant that as an American line, Oceanic like Matson, would enjoy a monopoly on a domestic route excluding foreign ships from carrying passengers or cargo. At a stroke this rendered the successful joint Oceanic-Union S.S. Co. Antipodes service unworkable as Moana could no longer participate in the lucrative Hawaii-Mainland sector of the route. Ironically, American expansion in the Pacific which owed much to Oceanic, put the company and its New Zealand partners in a difficult position and engendered competition instead of profitable and efficient cooperation. As events proved, it also facilitated the rapid rise of Matson on the Mainland-Hawaii trade at expense of Oceanic as it concentrated solely on that route.

Union S.S. Co. began negotiations with the New Zealand Government towards a subsidy for a parallel route of its own from San Francisco, but calling instead at Tahiti and Raratonga rather than Hawaii. For its part, Oceanic began its own lobbying with the U.S. Government for an expanded mail contract and subsidy to replace Alameda, Mariposa and Union's Moana with three new ships maintaining a three-weekly service to Honolulu, Pago Pago (American Samoa since 1899 when the island was partitioned by treaty between Germany and the United States), Auckland and Sydney. It was the beginning of a remarkable period, indeed a Golden Age, of trans-Pacific services to the Antipodes that would flourish up to the Second World War and represent the only real American competition to British lines on the imperial sealanes.

In addition to renegotiating its U.S. Mail contract, Oceanic lobbied for passage of the Hanna-Payne Shipping Bill (introduced by Sen. Mark Hanna (R-Ohio) on 19 December 1899, the first of several unsuccessful Whig Republican efforts to spur development of the American Merchant Marine through direct government subsidies to private shipowners. These were all variation of "differential" payments to offset the greater operational and labor costs incurred by American flag operations vs. foreign flag lines. These were opposed by Democrats who objected to public monies subsidizing private firms.

That the U.S. Merchant Marine was at its nadir was shown by dismal example. In 1897, British and German tonnage carried 85% of U.S. grain exports. Not a single U.S. flag merchant ship passed through the Straits of Gibraltar or the Suez Canal in 1898. Hamburg, then the third largest port in the world, had not seen an American flag ship in 30 years. And not a single U.S. flag ship entered the port of Buenos Aires in 1897.

But there were stirrings of a modest revival, not surprisingly centered on the East Coast to Cuba route with Cramp delivering Havana to Ward Line in January 1899 and on 7 February Plant Line placed an order with Cramp for a new steamship; "to have more extensive passenger accommodation than any vessel ever built in the United States excepting the two big American Line liners, the St. Paul and St. Louis." The ship would be 400 ft. by 50 ft. and have an 18-knot maximum speed. Next, the Pacific, long the only somewhat level playing field against foreign passenger and mail lines for American companies, would see an awakening.

Two and possibly three magnificent steamships are to be built by the Oceanic Steamship Company this year to ply between this port and Sydney, Australia. They will be of 6000 tons burden and will have a speed of seventeen knots an hour. The indications are they will be construction at the Union Iron Works, although that has not yet been decided.

San Francisco Chronicle, 22 January 1899

On the occasion of the Annual Shareholders Meeting of the Oceanic Steamship Co. at San Francisco on 21 January 1899, John D. Spreckels announced an ambitious newbuilding program entailing two or three new 6,000-grt, 17-knot steamers for the Antipodes service as well the re-engining and reboilering of Alameda and Mariposa for other duties.

Paramount in these plans was speed, with two objects in mind. One was to reduce the transmission time of the English mails to Sydney via San Francisco from 37 days (compared to 34 via Suez and 40 via Vancouver) to 30 days. And the other was to qualify for the augmented operational subsidies being proposed by the pending Hanna-Payne Shipping Bill. This would increase the existing mail subsidy of $10,478 per voyage to the Antipodes to $21,136 for 6000-ton, 17-knot ships. Such plans were also encouraged by the company's high stock prices and windfall profits arising from transport work during the Spanish-American War. Oceanic's reported 1898 net income of $177,776 for its regular trade but considerably augmented by $54,608 for the chartering of Australia for Alaska service and by $93,173 for transport charter to the U.S Government during the war.

With the new ships, Spreckels aimed to offer a 5½-day passage to Honolulu at 16 knots and then average 15 knots to the Antipodes to fulfill Oceanic's role in achieving the 30-day transit time from London to Sydney. The Chronicle added that the proposal "will undoubtedly be promptly acted upon. The reason is that much traffic, both freight and passenger, is being diverted from San Francisco to other ports, especially to Vancouver, B.C., by the inability of the present vessels of the line to accept all of the business offered… the prospects are that when the two or three large steamers are finished a fortnightly service will be established between San Francisco and Sydney with stops at Honolulu and Auckland."

On his first visit to Washington, D.C. in two years, John D. Spreckels arrived there on 1 March 1899 from Philadelphia (to visit a certain well-respected shipyard there) and also had a meeting with President McKinley the following day. "Mr. Spreckels says here to inquire about the chances of the Hanna-Payne shipping bill, and has ascertained that it is almost certain to pass at the next session, as it seems to be a very popular measure with the Senators and Representatives. In the event of its passage Mr. Spreckels' company (the Oceanic) will build three more fine vessels to ply between San Francisco, Honolulu and Australian ports." (The Call, 2 March 1899).

The projected construction of three large modern steamers for the Oceanic Steamship Co. of San Francisco would seem to be contingent upon the passage of the Hanna-Payne bill, according to Mr. John D. Spreckels of San Francisco who is now in the east on matters relative to the award of the contract. In an interview, published a few days since, he is quoted as saying:

'Contracts for the vessels have not yet been awarded, and will not be till I learn the exact status and prospects of the Hanna-Payne shipping bill, which is now before the House. I consider that this is an excellent measure, well calculated in every respect to encourage the growth of such a merchant marine as we should have. The Hanna-Payne bill will, of course, benefit the ship owners for the first few years, but it will eventually be of benefit to the farmers and growers. It will give an immediate stimulus to ship building. The result of that will be that, in a few years, we will have enough ships to start a lively competition among the owners, in which case the owners will be able to do without the subsidy and give the farmers the benefit of it. Some one wanted an amendment attached to the bill giving the farmers a bounty, but thai is wholly unnecessary, and it would, in my opinion, have a decided tendency to defeat the bill. The farmers will get the benefit of it eventually. The growth of the shipping, as fostered by the measure, will resemble the growth of the steel rail industry.

"The three ships which we propose to have built will be of 6,000 tons burden each, and of 8,000 horse power. They are calculated to have a speed of 17 knots, and a bunker capacity of 2,000 tons, with a freight capacity of 2,500 tons. They will have accommodations for 175 first class passengers, 100 second class and 100 steerage. They will be twin-screw steamers, 400 feet long by 50 feet beam. These are the dimensions and capacities of the ships as proposed, but they are liable to be changed. In fact, whether these dimensions will be adhered to depends very much on whether the Hanna-Payne bill goes through as it stands. We have three ships now running between San Francisco and Australia, which have the required speed, under the law of 1892, but they have not the required tonnage."

Marine Review, 9 March 1899

If the Hanna-Payne Bill eventually went nowhere, negotiations with the U.S. Post Office were sufficiently promising to spur Oceanic to proceed with its plans for three new 6,000-ton, 17-knot steamers in March 1899. Even without the spur of additional government subsidy, the boom in American overseas trade and commerce, especially to Cuba, suddenly flooded shipyards with new orders. Yards that had long suffered from idle slipways were now hard pressed to meet the demand and Oceanic's timing could not have been worse especially given the requirements of new and faster ships any new mail contract would demand within a tight deadline.

Oceanic had intended to place the order for three new ships with Union Iron Works of San Francisco and there ensued a series of meetings and negotiations between John D. Spreckels and Union's Irving M. Scott but "owing to the number of contracts in hand it was found impossible to build the vessels in the specified time. Mr. Spreckels wants to see the vessels in commission in March or April 1900 at the latest" asserted the San Francisco Call on 5 March 1899.

|

| Announcement of the order for the three new ships was predictably lavished reported in the Spreckels' owned San Francisco Call newspaper. Credit: San Francisco Call, 5 March 1899. |

San Francisco's fleet of ocean-going merchant steamers will have three of the largest and best appointed vessels of their class ever seen in the Pacific added to its number before 1900 is very old.

San Francisco Call, 5 March 1899

The Oceanic Company is making a great advance in the pathway of progress, but other floating palaces will be instituted, till every part of the mighty ocean is crossed and recrossed by the furrowing keels of the mighty commercial fleet of the future.

The Hawaiian Star, 10 March 1899

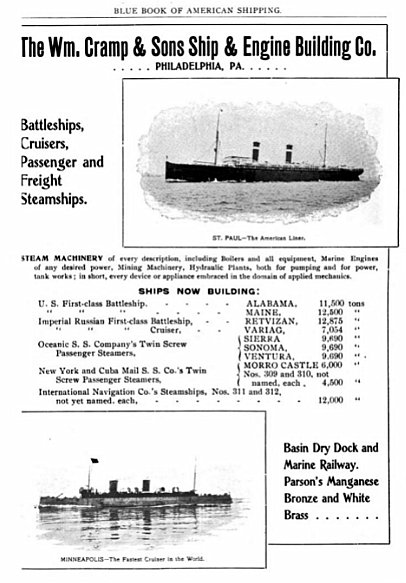

So it was that Oceanic turned to the yard that built Alameda and Mariposa-- Wm. Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia. The Gilded Age established the undoubted supremacy of Pennsylvania as the nation's workshop, the font of American industry and the source of very stuff, from coal and coke, to steel and oil that made it possible-- from Pittsburgh in the West, home of Carnegie, Frick and Westinghouse to Philadelphia in the East, headquarters of Baldwin Locomotives, J.G. Brill streetcars, Pennsylvania Railroad, "The Standard Railroad of the World," and Cramp & Sons, the nation's pre-eminent shipyard yet one of many flourishing yards that made the Delaware River the Clydebank of North America.

|

| "A Bird's-Eye View Cramp's Ship-Yards, Delaware River, Philadelphia" c. 1898 |

On 5 March 1899 John D. Spreckels announced that an order had been placed with Cramps for three 6,000 grt ships which would be 1,000 tons bigger than Pacific Mail's China (5,069 grt 440 ft. x 48 ft.) and measure 450 ft. in length with a 50-ft. beam. To accommodate 175 First, 150 Second and 100 Steerage, each would be powered by twin-screw triple-expansion engines developing 8,000 horsepower and giving a contract speed of 17 knots. They could carry 2,500 tons of cargo and, significantly, have refrigerated space for the carriage of Australian and New Zealand frozen mutton and beef and a 2,500-ton coal capacity reflecting their 6,000-mile route. Further, "They will be built to comply with the navy regulations and when in service can be turned into auxiliary cruisers inside of thirty-six hours." The contract price of the ships was not stated at the time but on 3 June Oceanic issued bonds totalling $2.5 mn. to "pay for three new steamers." and its 1900 report to shareholders revealed the cost of the new ships totalled $1,690,302.

The Call reminded its readers of Cramp's achievement with Oceanic's existing pair: "The Alameda and Mariposa were built by the Cramps, and two better vessels were never turned out of a shipyard. They have now been in commission nearly sixteen years, and never had a serious mishap. Year in and year out they have been making the 6000 mile to Sydney and 6000 miles back to San Francisco with the regularity of clockwork, and far more punctuality than the trains… If the Cramps were able to turn out two such vessels in 1883, what will they be able to do now with perfected plant and added experience? The three new vessels will undoubtedly be a credit to San Francisco, and will spread the fame of California among the Southern Seas."

|

| Credit: The San Francisco Examiner, 10 March 1899. |

Spreckels' decision to give the contract to an East Coast yard was resented in many quarters in San Francisco and the object of a highly critical report in the San Francisco Examiner of 10 March 1899 which ridiculed the official Oceanic statement in The Call that the three new ships would "spread the fame of California among the Southern Seas" when the vessels would be built 3,000 miles distant, depriving some local 1,200 men of potential work and questioning that Cramp could deliver the ships any faster than Union Iron Works. John Spiers, President of the Fulton Engineering and Shipbuilding Works was quoted: "It is a pity that Mr. Spreckels did not have the steamers built in California, but I suppose it was a question of saving money. It could hardly have been a question of time. The Union Iron Works could get the material out from the East in about two weeks, and that is no delay at in such a contract… There is one thing certain, though-- if the Cramps can build them in a year, the Scotts can. The Union Iron Works can do anything and in the same time, that can be done in the Philadelphia shipyards. Anyone who knows anything about shipbuilding knows that this statement is true."

For his part, Henry T. Scott of Union Iron Works denied that the issue of delivery time had never come in his discussions with Spreckels and that work for the yard was sufficiently scarce that he had been obliged to lay off 1,200 workmen. When Mr. Spreckels returned to San Francisco on 15 March, in company with H.W. Cramp, Secretary and Treasurer of Cramp Shipbuilding, he told a reporter of the Examiner: "I am not in the mood to be interviewed tonight, I am fatigued with my long overland trip." while when asked if he was surprised to have gotten the contract over Union Iron Works, Mr. Cramp replied, "Well, we're not sorry, but then I am not talking for publication, and particularly not for the Examiner. I refuse to be interviewed." Of course, as events proved Cramp delivered all three ships many months late.

The reality was that Cramp was overwhelmed with new contracts and while expanding its plant and workforce to meet the demand, the construction of the new trio was fraught with delays and deficiencies. The Oceanic trio added to an already exceptionally full order book which included, famously, the construction of a battleship (Retvizan) and a cruiser (Variag) for the Imperial Russian Navy. Then there was yard no. 303 which was an intriguing progenitor of a "stock" Cramp moderate size, fast liner which had been ordered on 7 February 1899 for Plant Line's Gulf Coast-Havana run. Upon the the death of Henry Plant that June and the ensuing sale of his ships to Henry R. Flagler, the hull was bought on the stocks by a regular Cramp customer, Ward Line, and completed as Morro Castle. The design formed not only the basis for three succeeding Cramp-built Ward liners (Merida, Mexico and Saratoga), but the new Oceanic trio.

Those three new steamers will be models of their kind. They are modeled on lines similar to the new Plant steamer, and will form a valuable addition to the American trading fleet in the Pacific Ocean. Secretary C.T. Taylor, Cramps' Ship & Engine Building Co.

Philadelphia Inquirer, 7 March 1899

Indeed, the Spreckels ships were dimensionally identical and almost visually, too, right down to the typeface of the letters that spelled their names on the hulls and were also twin-screw, triple-expansion engined. It was the all the more remarkable considering Morro Castle was to ply a route of some 950-miles whereas her Oceanic cousins' traversed some 7,500 miles each way. Sadly, they all shared more than their fair share of mechanical deficiencies although these were more concerned with their machinery and auxiliaries than their naval architecture and construction. In a hurry, the Spreckels settled on an unproven "off the shelf" design to some extent and while one that would eventually endure for three decades, certainly initially reflected little credit on the builders.

It certainly started with the unbounded confidence, bluster and swagger that defined the era. The Age (Sydney) of 13 April 1899 reported that "the contractors undertake to turn out these ships within the year" which was, by any standards of that day (or indeed this) remarkably fast and what prompted Spreckels to place the order. On 9 May it was reported in the Philadelphia press that "material for the ships was now arriving at the yard...then working on the new Ward liner Morro Castle and the Russian cruiser Variag among other vessels." The Times (Philadelphia) said on 14 May "This contract was regarded by the Cramps as a signal victory, inasmuch as it implies the construction on the Atlantic when they are to go into service from a Pacific port 14,000 miles away."

"No time is being lost in the building of the three ocean greyhounds for the Oceanic Steamship Company. The keels of all of them have been laid in Cramp's shipyard at Philadelphia, and March next should see one of them in San Francisco." (The Call, 24 June 1899). Hot on the heels of Havana, Mexico and Morro Castle recently launched by Cramps, the keel of no. 304 was laid down at Kensington on 19 June 1899, no. 305 on 22 June and no. 306 on 4 November, the latter having to wait for the launch of the Russian cruiser Variag, to clear the slipway.

The Call in the same issue announced that the Oceanic trio would be named Ventura, Sonoma and Sierra, but either it got the names mixed around or Oceanic later decided to name the first Sierra and the last Ventura. Even if Sierra was a California/Nevada mountain range, Sonoma and Ventura conformed to the company's California county inspired nomenclature. They were names that the ships would, through more three decades of service, enshrine in the annals of both their company and country's merchant service as well becoming household names along their 7,200-mile route from America to the Antipodes.

Construction progress was painfully slow from the onset. Much of the initial delay was caused by a critical shortage of steel. An era of unbridled progress and astonishing industrial growth was built on steel and there was simply not enough of it at the turn of the century. On 15 August 1899 the Reading Eagle reported that Cramps had laid off 1,500 riveters, platers and iron workers for want of steel, noting that "the Plant Line ship is now in frame but waiting for steel beams and stringers" and "work is almost at a standstill" on the two Oceanic ships.

The Gilded Age also saw the rise of organized labor and unions as a counter point to often dire conditions, long hours and low wages that produced the almost limitless profits enjoyed by the magnates, barons of industry and trusts. Construction of the new ships was further slowed by a strike at Cramps which began in early October 1899, but The Call kept up its cheering reports, including a 30 October one on the visit to Philadelphia by George W. Bell, the American Ambassador to Australia, who, after seeing the ships building at Cramps, said Mr. Cramp had "told him that they were the equal of any ships of their class now afloat and vastly superior to anything now on the waters of the Pacific Ocean. They are large, roomy, comfortable, and combine every modern device for safety, with engines capable of driving them at a speed fully two knots faster than any steamer now running out of San Francisco. The first of these magnificent ships will be completed about the first of next May and the other will follow at intervals of months."

|

| Oceanic's 1900 sailing list announcing the new ships and the new mail service to the Antipodes to commence on 1 November. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

1900

By the action of the Postmaster General in awarding the contract for carrying the Australian and British closed mails between the United States and Australia to the Oceanic Steamship Company another evidence is given of the superiority of the San Francisco route to and from Australasia and the United States and Europe. The mails of course are forwarded by the shortest, quickest and safest route available, and it was by demonstrating its superiority in these respects over competing line that the Oceanic Steamship Company obtained the contract.

The award is certain to give satisfaction to the public, for the Oceanic is one of the oldest and most reliable steamship lines upon the Pacific, and its carrying service can be relied upon for speed, certainty and efficiency. The regularity of the mails will therefore be assured as far as anything can be which is liable to the accidents of the world, and the advantages of to the commercial community will be notably great.

The Call, 11 April 1900

U.S. Postmaster General Charles Emory Smith advertised for bids for a service from San Francisco to Antipodes "performed by vessels of the second class, 17 trips per annum, time of voyage to be twenty-one days. Under the second-class specification vessels must not be less than 5,000 tons registers, capable of 16 knots speed and constructed to meet the requirements specified for auxiliary naval cruisers. The rate of compensation for such vessels not to exceed $2 per mils for each outward voyage." On 8 March 1900 Oceanic submitted its formal bid to the Post Office for route 75, accompanied by a $40,000 bond. It was the sole bidder.

Pressure to complete the new ships intensified on 31 March 1900 when J.D. Spreckels & Bros. were advised by the U.S. Postmaster General of their award of a new mail contract for 10 years to take effect 1 November to be tri-monthly to Honolulu and Pago Pago and Auckland and pay $2 per mile. Sailings would be every three weeks instead of four and the transit time from San Francisco to Sydney reduced from 25 to 21 days. This would net the company approximately $250,000 per annum. In 1903, the exact amount came to $245,420 plus $7,000 for Samoa-San Francisco northbound mails. The new service would come into effect on 10 November. At the same time, the colonial government of French Tahiti granted Oceanic a mail contract for a regular service from San Francisco to Papeete which would pay $30,000 per annum for a single ship making 11 voyages. The company continued its negotiating with the Australian and New Zealand government for mail contracts with each. Efforts to secure anything more than a poundage rate from the Australians were ultimately frustrated but in 1903, the New Zealand Government entered into a mail contract with Oceanic paying £25,000 per annum.

Oceanic pointed out that the United States had itself a good bargain with its mail contract which enabled for about $250,000 per annum:

- The supplanting of a foreign vessel by one under the American flag.

- The building of three American steamships aggregating 18,459 tons register, of the auxiliary-naval type.

- Reduction of time in the delivery of mails between terminals from twenty-four and three-fourths days to twenty-one days.

- An increased number of voyages from 13 to 17 per annum.

- Greatly increased facilities for transportation of merchandise.

- An increase in total number of crew from 182 to 471, all whites, and shipped in the United States.

- An increase in wages paid of $144,120 per annum.

- Employment of 18 American boys as cadets, as required by the law of 1891.

- The availability to the United States Navy of three steamships of the auxiliary cruiser type, each capable of mounting at least four 6-inch guns and a large complement of smaller caliber, that have a steaming radius without refueling of 8,250 statute miles at 15 knots average speed, or shorter distances at 17 knots, that are always maintained at the highest rating known to maritime commerce.

It was further asserted that "The schedule time required under the contract calls for an average speed throughout the entire voyage of approximately 15 knots per hour. The distance in nautical miles is 7,210, and most of the voyage lies within the tropics. No other steamship line in the world performs such a fast service under similar conditions as to climate and distance."

|

| Miss Cassie L. Hayward, Godmother of Sierra, and daughter of Oceanic Captain Henry Hayward. Credit: The Call. |

Months late, no. 304 was finally christened as Sierra at Kensington on 29 May 1900 by Miss Cassie L. Hayward, daughter of Capt. Henry M. Hayward.

… as she smashed the riboon-redecked bottle over the bows of the ship she exclaimed: 'I christen thee Sierra, ocean's price, and bid thee God-speed in thy career of ploughing oceans far and near… from the upper deck of the big merchantman flashed numerous signal flags and the national colors…. Shortly after 2 o'clock the vessel was released from the ways, and as she started gracefully down the incline to receive her baptism Miss Cassie Hayward broke over her bow a bottle of sparkling wine, as she repeated the christening formula. Loud cheers from the mass of spectators, together with the toots of a hundred steam whistles, afloat and ashore, greeted the Sierra as she swept into the river and pointed her nose up stream. Several tugs at once made fast to her and she was soon safely moored alongside a pier. Immediately after the launch, a luncheon was served to the guests.

Philadelphia Record, 30 May 1899

|

| Credit: The Call, 11 June 1900. |

The day was an ideal one for such an occasion. The morning was cool and slightly overcast with clouds, but almost at the moment when the final wedge was loosened from under the Sierra's keel the sun shone brilliantly over the animated scene. The river was without a ripple and the new creation of the marine architects glided with the grace of a swan down the smoking ways and for the first time dipped her beak into the glistening waters.

The Sierra took the water exactly at 2.20 p.m. amid vociferous cheering and the din of whistles on factories and passing river craft. Within ten minutes she had been picked up far out in the stream and towed back to her moorings at pier 86, where the work of completion will be vigorously pushed that she may be in service by next fall.

The Times (Philadelphia), 30 May 1900

Among those present for the launching were Charles H. Cramp, president, and Henry M. Cramp, treasurer, Capt. Henry M. Hayward and daughters Misses Cassie L. and Edna Hayward, Naval Constructor Hanscom, Asst. Naval Constructor Robinson and Capt. Brownson and Lt. Cmdr. Badger of U.S.S. Alabama. It was forecast at the time that Sierra would be delivered by 1 September 1900.

|

| Miss Alice Von S. Samuels, Godmother of Sonoma, Credit: The Call. |

Sonoma was launched at Cramps at 10:33 a.m. on 7 August 1900 by Miss Alice Von S. Samuels, the daughter of Wm. S. Samuels, inspector of Lloyd's agency in Philadelphia.

There was no large gathering of public officials at Cramp's shipyard yesterday, but the launch of the huge Oceanic Line steamer Sonoma was as great a success from a spectacular point of view as any of the launched that have made the great Kensington yard famous the world over. The Sonoma slide down the ways and took her first dip into waters of the Delaware about 10.30 o'clock, and there was not a hitch of any kind in the carefully arrange programme. All the workmen employed at the place and quite a number of visitors were on hand when the customary bottle of win was smashed on the vessel's down by Miss Alice Von S. Samuels, the handsome daughter of Captain William S. Samuels, inspector for Lloyd's agency. There was a hearty cheer as the big hull glided into the water and all the steam whistles in the vicinity shrieked out a noisy salute.

As the freshly painted hull glided from the ways, there was the usual accompaniment of shrill voiced whistles from the Cramp plant and passing river craft. The soul-searching of the cruiser Variag and the new Ward liner Morro Castle added to the general chorus. As Miss Samuels shattered the bottle of wine across the port bow of the Sonoma, the sharp impact of the bottle against the hull caused a portion of the contents to spray the faces and clothing of those nearest her.

Philadelphia Record, 8 August 1900

Attending the launch were Capt. Hayward and his two daughters, Henry W. Cramp, Edwin S. Cramp and Courtland D. Cramp.

The Philadelphia Record on 19 August 1900 reported that "activity in shipbuilding continues unabated at Cramp's shipyard, and the rush is hastening the completion of facilities which practically double the output of the plant."… "feverish activity in every corner of the workshops." Feverish but not timely, and the Sydney Morning Herald of 5 September informed its readers that: "Owing to the strike in Philadelphia, there has been a lot of delay in her getting her finishings, and she will be at least two months later than expected. It is thought she will be there by the middle of November. The time for the arrival of the other two new steamers is also doubtful." It was originally planned to have all three on the run by 12 December with Sierra first on 5 September, Sonoma sailing from San Francisco on 31 October and Ventura on 12 December. Now, it would be necessary, at very least, to have Mariposa make an additional round voyage to the Antipodes, returning to San Francisco on 16 November when it was hoped Sierra would be able to relieve her. To this effect, Oceanic announced on 26 September that Sierra would sail on her maiden voyage on 21 November, under Capt. C. Houdlette, formerly of Mariposa.

|

| Credit: Oakland Tribune, 27 September 1900 |

On 26 September 1900, the third of the ships was sent down the ways at Cramps by Miss Elsie Cronsmiller, niece of John D. Spreckels.

Through the building of great ocean going steamers and furnishing the capital to operated them Philadelphia is now taking a hand in the development of trade between the western shores of this country and the isles of Pacific, made the more profitable by the policy of President McKinley.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, 7 September 1900

The last Union S.S. Co. sailing on the joint service was by Moana which docked at Sydney on 28 October 1900. The Oceanic twins, too, made their supposed final voyages on the service, Mariposa from Sydney on 24 October (arriving at San Francisco on 10 November) and Alameda departing Sydney on 4 December and coming into San Francisco on Christmas Eve.

|

| Sierra in dry dock at Cramp's on 10 September 1900 where her hull was cleaned and painted before her trials. Credit: Mariners Museum |

Meanwhile, Sierra was finally nearing completion and after painting, was floated out of the dry dock at Cramps on 12 September 1900. On 3 October the Philadelphia Record reported: "It is expected that the new steel steamship Sierra, built by the Cramps Shipbuilding Company for the Oceanic Steamship Company, for service between San Francisco and Australia, will make a trial trip to-day. The owners of the vessel are in a hurry for the craft, and the contract for her delivery expired some time ago."

|

| Another view of Sierra in dry dock. Credit: Mariners Museum. |

|

| One of an ongoing series of panoramic photographs of the Cramp shipyards during its amazingly productive 1900 with Sonoma (left), Sierra (middle) and the Russian cruiser Variag (right) fitting out. |

Returning from the trials of the Russian cruiser Variag, Edward S. Cramp met with John D. Spreckels on 6 October 1900 before both embarked on Sierra that afternoon for her trials which lasted until the 9th. On her return, the Philadelphia Record reported that the trials had been ""successfully run at sea in the stormiest weather. The builders guaranteed a speed of 16 knots knots which was necessary because of mail contracts. And with was exceeded by a knot; the new vessel returning with 17 knots an hour to her credit." The Philadelphia Inquirer added: "the vessel steamed up the Delaware with the number 17 painted on her stack."

|

| By autumn 1900 Oceanic began advertising the new ships and services, both the improved one to the Antipodes and the new route to Tahiti. |

Little time was wasted in preparing Sierra for her epic delivery trip to the West Coast, recalling this was 14 years before the Panama Canal was built and San Francisco was a 14,000-mile voyage away, around South America and through the Straits of Magellan. Even more audaciously, it was planned that she sail there nonstop (which had never been attempted), without refuelling, and make the journey in 33 to 36 days. With Capt. H.C. Houdlette in command, Sierra set out at 1:00 p.m. on 11 October 1900 on the longest single voyage she would make in her 32 years. Filling out her officer staff on that first trip were Chief Officer J.H. Trask, Purser N.C. Walton, Chief Steward W.N. Hannigan, Chief Engineer W.H. Netman and Surgeon Dr. Souls.

|

| Finally finished, an immaculate and very smart looking Sierra in the Delaware River. |

Leaving Philadelphia on 11 October 1900, Sierra passed Cape Henlopen the next day, detained for over 13 hours off Cape Virgin, again at Sandy Point (St. Croix) and another 14 hours in the Straits of Magellan and with her voyage already extended beyond the anticipated 35 days, she had to call at Coronel for one day and 15 hours to take on extra coal. From Cape Pilar to Coronel, she met with a gale with headwinds and high seas, but from there all the way to San Francisco enjoyed fine weather.

|

| The Call enthusiastically covered Sierra's "Splendid Dash" from her builders to San Francisco. Credit: The Call 25 November 1900. |

The Oceanic Steamship Company's new steamship Sierra arrived from Philadelphia yesterday morning. She made the run in record-breaking time and came into port looking the ocean greyhound that she is."

Captain H.C. Houdlette, who brought the new flyer out, says she is the best sea boat he ever set foot on, while Chief Engineer Nieman says is as easy to handle as a yacht. Added "From the time we left Philadelphia we have never been under full steam, but nevertheless she ran along at a 12 and 13 knot gait as though was nothing was the matter. When it comes to making mail time, I think she can easily do the run to Honolulu in five days when asked. I have been at sea a few years myself, and I never saw a pretty set of engine in a ship all my life than those that drive the Sierra. They work like a clock and when called upon will make the Sierra show her heels to anything on the coast."

There were crowds down to see the new steamship yesterday. Her cabins and staterooms were inspects and everything in the shape of furnishing was pronounced good. In the second cabin the accommodations are equal to anything in the 'first class' on the coast steamers. Everywhere there are electric fans, and there are plenty of bathrooms aboard. Hot and cold water is distributed from one end of the ship to the other, and the electric light system is perfect.

In every details there is a tendency to the luxurious, and in no instance does the decoration prove inharmonious.

San Francisco Call, 25 November 1900

Sierra came triumphantly into San Francisco on 25 November 1900 and despite the longer than expected journey time, still managed to break Alameda's record of 45 days set on her own 1883 delivery voyage. Sierra's total time for the 14,000-mile trip was 39 days and 16 hours including 2 days 22 hours 10 minutes detention on her stops en route. "During the entire trip the Sierra behaved splendidly, proving herself a fine sea craft" and officers "speak in praise of the seaworthiness of the Sierra" were among the kudos to the ship by her officers and crew reported by an enthusiastic press. Almost as soon as the somewhat sea-stained vessel docked at the Pacific Street Wharf at 7:30 a.m., she was thronged by visitors, not the least of whom was Claus Spreckels and that afternoon a party of business men were shown aboard by John D. Spreckels.

|

| Even the rival San Francisco Chronicle gave Sierra's arrival lavish coverage. Credit: San Francisco Examiner, 25 November 1900. |

|

| As did the San Francisco Examiner using another one of Detroit Publishing Co.'s formal portraits of Sierra in the Delaware River. Credit: San Francisco Examiner, 25 November 1900. |

The departure of the Oceanic Steamship Company's steamship Mariposa on Tuesday evening for Auckland, N.Z. and Sydney, Australia, marked the beginning of a new era of quick and more convenient mail and passenger service to those far off lands, as well as an increase in the business of San Francisco.

San Francisco Call, 25 November 1900

The excitement over Sierra's arrival was somewhat mitigated by the fact that she had rather missed the party already. It fell, instead, to the venerable Mariposa to take her 22 November 1900 sailing to the Antipodes, inaugurating the new mail service. She had aboard the London mails which had been dispatched from the capital at 9:15 p.m. on the 10th and scheduled to reach Auckland 10 December and Sydney the 13th. In comparison, P&O's Victoria left London 1 November, calling at Port Said 13th where she collected the last London mails from transhipped from Brindisi on the 11th. She would arrive Sydney on 15 December, two days later than Mariposa and Auckland on the 20th, a week later than the Oceanic liner. Once in service, the new ships would cut another two days off the passage.

Although reported as a doubtless triumph in the effusive press coverage, it did not take much reading between the lines to discern that Sierra had a very difficult delivery trip, beyond the rigors of taking a brand new ship from the builders yard on a 14,000-mile right around the South American continent. There were teething problems aplenty in the engine room and her detentions en route were on account of these as well as deficiencies in the performance of her twin screws. The Spreckels, too, seemed unhappy with much of her furnishings which were landed and replaced before she set off on her maiden voyage and had decided that her hull should be repainted white as well. A replacement set of screws was cast and sent from the east by train with the idea of shipping them aboard for the run to Sydney where they would be installed in dry dock there.

San Francisco Chronicle of 26 November 1900 reported "although no visitors were supposed to be admitted to the new steamer Sierra yesterday, and all expressed admiration over her fine appearance. The day was rainy and the ship was in no condition to be examined from a critical standpoint, but those who were so fortunate as to be passed by the guard at the gangplank were well repaid for the trouble going to the steamer. The work of cleaning the Sierra and painting her a snow white will begin today. By December 12th, when she is to sail for Sydney on her first trip, the steamer will be in first-class condition. Nearly all her cabins have been engaged for the trip." While the Call the same day informed its readers: "yesterday a gang of men was at work painting and scrubbing and removing the signs of her long voyage around the Horn. In a few days she will begin to look like the ocean beauty she is, and then the general public will have a change to see her in all her war paint. The Sierra is a handsome vessel and from truck to keelson even an expert cannot see anything to find fault with." Meanwhile, Sierra was shifted from the Pacific Street Wharf to the Spreckel's sugar refinery pier for the work.

More candor slipped in when on 30 November 1900 the San Francisco Examiner reported that Sierra is "in the stream taking in coal and being put in readiness for sailing to Australia on December 12th. The machinery of the steamer is being overhauled, for it is not yet in smooth running order. On the voyage out from Philadelphia several stops were made on account of it." while the Chronicle on 5 December, remarked that "All the furnishings of the steamer have been put back in place, a lot of brightening up has been done and the visitors will see the Sierra at her best. The hull is being painted white." It was only later that more details as to the delivered condition of the vessel was revealed:

After her [Sierra] arrival repairers were busy on her almost up to the time she sailed, and then she was not in a condition satisfactory to her owners. More than once on her voyage out she had to be hove to to repair breaks. The worst trouble was with her feed and lifting pumps. The latter could not stand the pressure required of them, and they were continually pulling away from their fastenings. Upon arrival here the Cramps were telegraphs to to send out proper pumps. The feed pump reached here in time to be put in place, but the Sierra sailed for the colonies with original lifting pump, and as a result she made a very long passage to Honolulu.

San Francisco Chronicle, 9 February 1901

|

| The Elegance of The Gilded Age captured in this superb illustration depicting the inspection of the new Sierra by invited guests. Credit: The Call, 6 December 1900. |

On the morning of 5 December 1900 Sierra was back at the Pacific Street Wharf where she was opened to inspection by invited guests from 3:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m.

The Oceanic Steamship Company's new palatial steamer Sierra was thrown open for inspection yesterday. For three hours the invited guests came and went, and on every lip was praise for the new mail boat.

J.D. Spreckels received all the visitors and among the prominent guests who inspected the Sierra with a critical eye was Claus Spreckels. He went over the big liner from stem to stern and suggested here and there an alteration that will improve the comfort of the traveling public.

San Francisco Call, 6 December 1900

As all the furnishings had been been replaced since the Sierra arrived from Philadelphia a few days ago, the vessel's interior was very attractive, and was highly praised for its up-to-date features.

San Francisco Chronicle, 6 December 1900

On 10 December 1900 Sierra left her berth and "took a spin on the bay for the purpose of adjusting the compasses." (Chronicle) and then returned to finish loading a heavy cargo and preparing to receive a full passenger list, it being reported by the Call "there is not a vacant stateroom in the ship. The second cabin is taxed to its limited and the steerage is well filled. The handsome liner has been painted white and looks better than ever in her new colors."

|

| Predictably but wonderfully enthusiastic, Spreckels' The Call lavishly recorded every moment of Sierra's entry into service. Credit: The Call, 14 December 1900. |

Sierra's maiden voyage finally was to commence at 9:00 p.m. on 12 December 1900 when the she was described by the Chronicle as being "laden with freight and shining in a coat of white, presents a more attractive appearance than she arrived her after her long trip from Philadelphia." In the event, the trans-continental train with mails from England was involved in a wreck in the Rockies and she did not get away until 3:00 p.m. the next day, Her passenger list of 200 First, 80 Second and 40 steerage was the largest cabin list yet to sail from San Francisco and her outbound cargo included salmon, shoes and boots, lumber, bicycles and canned goods. It proved a tricky departure owing to a strong flood tide and Sierra was carried back against the pier, scraping her fresh coat of white paint until the tug Relief Pilot Newt Jordan got her in hand and off on her way by 3:30 p.m. "Once out in the stream, all the near-by steamers gave the vessel a rousing farewell, there was a great shouting of the hundreds of passengers lining the rail and the Sierra's maiden voyage was auspiciously begun." (Chronicle, 14 December 1900).

The Oceanic Steamship Company's fine new mail boat Sierra got away for Honolulu, Pago Pago, Auckland and Sydney yesterday. As she pulled out into the stream every tug in the bay saluted her and the crowds on Pacific-street wharf cheered and waved their handkerchiefs to their departing friends. Never had a vessel such an auspicious start on her maiden voyage, and never has a big mail boat left boat left port in better trim for a long run. She was loaded 'just right,' and Captain Howard deserved all the praise he received for the excellent trim in which he sent the big liner to sea.

San Francisco Call. 14 December 1900

|

| Front page news in the Honolulu Evening Bulletin, 21 December 1900 |

In an era before wireless communication at sea, ships' arrivals were anticipated by schedule and often resulted in wasted hours vainly searching the horizon for their appearance off shore. Such was the case with Sierra whose already delayed first voyage was further retarded by one of the worst winter gales in recent memory so that she did not arrive at Honolulu on 18 December 1900 as expected but rather on the 20th. She was finally sighted off Koko Head at 7:00 p.m. and docked after a miserable 7-day 4-hour passage, recording daily runs of 194, 290, 288, 290, 256, 312, 362 and, on the last day, 89 nautical miles.

Meeting what Capt. Houdlette said was the worst weather he had seen in 11 years, Sierra hit gales en route westnorthwest beginning 14 December 1900, had to slow down and shipped a heavy sea forward which unshipped a derrick boom and smashing woodwork in front of the bridge. The atrocious conditions continued and on the 16th she shipped another sea, damaging deck fittings. Worse, the new screws on the fore deck began to shift and also caused her to dip her bows in the seas and had to be, at great peril to the deck crew, unlashed and were washed overboard. Only on the 17th did the weather abate, but she did still did not work up to full speed and there were clearly still issues with her machinery: "The Sierra has not 'found herself' yet, as Rudyard Kipling would remark. She is brand-new and stiff and awkward, and her different parts have not as yet shaken themselves together. She doesn't run as easy as she will by and by when she had a chance to find herself, and her parts have had an opportunity to get acquainted with one another."

|

| Credit: Hawaiian Gazette, 21 December 1900. |

As she lay towering and graceful alongside the Oceanic wharf yesterday, the great new steamship of the Oceanic Company, the Sierra was the admiration and delight of all who saw her. Honolulu, never having seen the Sierra before, made it a point to inspect the new boat while she was in port. Her officers permitted people to go aboard and look around, to wander from one end of the large vessel to the other, to wonder at her size, her beam, her depth, her power, her beauty and her elegant accommodations… In the afternoon, between four and five o'clock, Berger's band played aboard the Sierra. It was the Sierra's welcome to this port. There were many through passengers on the vessels deck when the music of the band made the afternoon gay and entertaining, and they thought as much of the band as the members of the band thought of the splendid Sierra.

Honolulu Advertiser, 22 December 1900

Sierra sailed south at noon on 21 December 1900.

1901

The service initiated by the arrival of the Sierra cannot fail to be of great importance to New Zealand. There is a possibility of some little delay in having the service fully established, but it can only be a matter of a few months till the Sonoma and the Ventura, sister ships to the Sierra, follow on the route, thus placing the facilities for travel across the Pacific far ahead of anything to which the people of New Zealand have been accustomed.

New Zealand Herald, 18 January 1901

Sierra kept Aucklanders anxious, too, and she she did not arrive as expected on 2 January 1901, the Auckland Star surmised "that a breakdown, possibly of a trivial nature, occurred in the engine-room." She finally appeared on the morning of the 4th, now four days off schedule time. It transpired that the port low pressure piston had broken on Christmas Eve, while nearing Pago Pago, necessitating stopping to disconnect it from the crankshaft and proceeding at a lower speed for the rest of the passage. She called at Pago Pago on the 28th. She did San Francisco to Auckland in 21 days 13 hours with stoppages of 19 hours 13 hours so her total steaming time was 20 days 17 hours 20 minutes. Her best day's run was 369 miles between Honolulu and Pago Pago.

Referring to the weather encountered between San Francisco and Hawaii, the Auckland Star reported: "Throughout the gale the steamer behaved excellently, proving herself a splendid sea boat. The passengers all speak in glowing terms of her steadiness and seaworthiness. Some little damage was caused to the deck fittings by green seas, which were taken aboard." The New Zealand Herald added: "throughout yesterday the steamer was thronged with visitors, who took a keen interest in the various appointments, and who were allowed the full run of the ship, the officers and crew being most courteous to all. The Sierra leaves for Sydney this morning, where the repairs to the broken piston will be effected." A celebratory luncheon was hosted aboard that afternoon attended by Union S.S. Co.'s Chairman and local officials.

As an embodiment of strength, speed, comfort and safety, the new mail steamer Sierra, of the Oceanic Steamship Company's line, which arrived yesterday from San Francisco, ranks among the highest class of American merchantmen.

The Daily Telegraph, 10 January 1901

Sierra left Auckland for Sydney at 9:30 a.m. on 5 January 1901 where she docked at the Union S.S. Co. pier on the 9th. That afternoon the Prime Minister of New Zealand, the Rt. Hon. R. Seddon, was a special guest of the officers and attended a welcoming reception aboard.

|

| Wonderful photographic coverage of Sierra's maiden departure from Sydney in The Sydney Mail, 2 February 1901. |

It was decided not repair the damaged piston during the turnaround at Sydney and Sierra sailed at 4:20 p.m. on 17 January 1901 on the return journey of her maiden voyage. This, too, was delayed by strong headwinds across the Tasman and her already diminished speed and she finally came into Auckland the evening of the 21st. By the time she sailed north at 11:00 a.m. the next day, Sierra was three days behind schedule. Sierra called at Pago Pago on 26 January 1901 after which one of her circulating pumps failed and she did not arrive at Honolulu until 3:00 p.m. on the 2nd and sailed for San Francisco later that day.

On account of an injury to one of the cylinders and minors mishaps the Sierra's first trip has not been particularly creditable, although the seaworthiness of the vessel has been highly praised.

San Francisco Chronicle, 10 February 1901

Two days late, Sierra ended a star-crossed maiden voyage when she docked at San Francisco on 9 February 1901, landing 85 cabin and 30 steerage passengers. On the outward trip, after leaving Honolulu, the low-pressure cylinder burst, and this greatly hindered the speed of the steamer. Leaving Sydney on January 30th, the Tasman offered up head winds and rough seas and she called at Auckland on 20-21st and Pago-Pago on the 26th. Fine weather, was experienced to Honolulu (3 February) and she made the crossing to San Francisco in 5 days 14 hours.

In the meantime, Sonoma, had been completed, ran trials and distinguished herself on her delivery and maiden voyage. Her trials had begun on 7 November 1900, departing Cramps at 2:30 p.m. for the course outside the Delaware Capes with Capt. Redford Sargeant in command and Edward S. Cramp aboard. Sonoma, under Capt. C.F. Harriman, left Philadelphia for San Francisco at 7:00 a.m. on the 17th, passing Pernambuco at noon on the 30th, entering the Straits of Magellan at 2:30 p.m. on 8 December and passing out of them at 10:30 a.m. on the 10th. She was favored with light to moderate winds throughout the voyage except for one strong northerly gale clearing the straits which slowed her down for 18 hours. Sonoma reached San Francisco at 9:00 p.m. on the 26th; her non-stop passage of 38 days 9 hours clipped 19 hours off Sierra's time. She did the 13,265-mile voyage at an average 14.84 knots with a best days run of 368 miles at 16.67 knots.

During all the trip from Philadelphia the Sonoma showed a capability for speed that surprised even her officers, and while in the straits, when she was running for an anchorage in advance of the tide, a speed of over eighteen knots an hour was recorded and her engines made 115 revolutions, or three more than on her trial trip. Mr. Anderson, formerly on the steamer St. Paul, came out on the Sonoma as the builder's representative. Frequently the steamer made 390 miles in twenty-four hour hours. The only fault noted was in the vessel's pumps.

San Francisco Chronicle, 28 December 1900

The reference to the defects on Sonoma's pumps reflected the same problems encountered by Sierra and detailed later by the San Francisco Examiner on 9 February 1901:

The Sonoma, the second of the fleet, encountered the same difficulties on her maiden voyage from Philadelphia. Her engine room, like that of the Sierra, was a workshop during the entire trip, and the engineer's department was worked to death. Day and night the men were kept going, and they succeeded in getting some service out of the pumps. The Sonoma arrived here in a little better condition than did the Sierra, but she too had to be turned over to the repair shops. The Risdon Iron Works had possession of her until within a day before she left port for the Colonies. Another telegram was sent to the Cramps and the new pumps came out here, not by fast freight, but by express, at an enormous cost to the shipper-- 15 cents at pound, it is said. The result was that the Sonoma went away with new feed and lifting pumps. She made a good run to Honolulu, but the work in the engine-rooms was a nervous strain on the men. Fourteen coal passers left the vessel as soon as she reached the islands.

Sonoma was dispatched on her delivery trip not completed inside with none of her carpets laid or furniture fitted in place and her superstructure not painted so all of this work, in addition, had to be accomplished en route.

Sonoma which had been in the upper bay since arriving, was shifted to the Pacific Street pier on 9 January 1901 to be made ready for her maiden voyage to Sydney on the 23rd including being repainted white. On the 12th, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that "a large number of mechanics are at work on the several decks of the new steamer Sonoma putting the vessel in shape to leave for Australia on the 23rd. All the furnishings originally place in the steamer have been temporarily removed and when the workmen have completed minor alterations will be replaced."

|

| An especially pleasing study of Sonoma, pristine in white, outbound on her maiden voyage. Note the U.S. Mail Flag occupies pride of her place at her mainmast gaff. |

Delayed by the late arrival of the English Mails, Sonoma sailed at 3:00 p.m. on 24 January 1901 "under even more auspicious circumstances than attended the departure of her sister ship Sierra a few weeks ago..."The steamer was inspected at her dock by thousand of persons prior to the moments of sailing and received high praise, the furnishing and generally fine appearance inside and out making the vessel an object of unusual interest. Many photographs of the steamer were taken after she backed into stream." (San Francisco Chronicle, 25 January 1901). She was commanded by Capt. K. Van Oterendorp, late of Alameda, with Chief Officer C.A. Holbert, Second Officer F.A. Jones, Third Officer G.A. Hill, Chief Officer C.A. Holbert and Chief Purser G.A. Hodson.

|

| Credit: San Francisco Call, 14 February 1901. |

The weather initially was no kinder to Sonoma than it had been to her sister, with a heavy gale endured for a day and a half after leaving San Francisco, with "a good deal of water shipped, but no damage was done." Honolulu was reached mid morning on 30 January 1901 and she called at Pago Pago on 6 February. By reaching Auckland on the 12th, in a steaming time of 16 days 3 hours 54 minutes, she had beaten Alameda's record of 16 days 22 hours 1 minutes set on her last voyage, averaging 15.75 knots. Sailing from Auckland at dawn on the 13th, Sonoma put in a splendid run on her first passage across the Tasman, sweeping past Sydney Heads on the 16th.

Considerable interested was manifested at Sydney in the arrival on Saturday [16 February 1901] of the A. and A. R.M.S. Sonoma an the Union S.S. Company's Mararoa, a cable from Auckland having mentioned that the two liner were racing across the Tasman Sea.

The Union liner left the wharf at Auckland at midnight on the 12th inst. And the Royal Mail steamer left the moorings at Auckland at 5 o'clock the following morning, the named vessel thus getting a start of five hours for the race across.

The first steamer to put in an appearance at the Heads on Saturday morning was the Mararoa, which entered at 7 o'clock. The Sonoma shortly afterwards was sighted from the South Head signal station, and entered Sydney Harbour at 8.45 a.m. Deducting the start the Mararoa had of five hours, the new mail steamer Sonoma thus gains a victory by 3 hours 15 min. The steaming of the Mararoa was 3 days 7 hours, and the Sonoma's actual steaming time was 3 days 3 hours and 45 mins.

The passage of the Sonoma is the record for the run across from Auckland to Sydney, beating that of the R.M.S. Moana, of the Union Line, which made the trip in 3 days 4 hours. On the first day out from Auckland the liner 425 knots, and on the second day she ran 413 knots, the average speed being 17½ knots per hour. From 'Frisco to Auckland her average was 16 knots per hour.

The Sonoma showed her splendid steaming capabilities through the run from the Golden Gate by breaking all previous records. Her actual steaming time from San Francisco to Sydney was 19 days 7 hours 39 min. The A. and A. liner also holds the 'blue ribbon' for the fastest run from Philadelphia to San Francisco. Her actual steaming time over that distance was 37 days 4 hours. Captain Von Oterendorp is in command and Mr. Little is chief engineer, and both are proud of the performance of the liner.

Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 18 February 1901

|

| Excellent photo of Sonoma sailing from Sydney on the return leg of her maiden voyage. Credit: Sydney Mail, 9 March 1901. |

Berthed at West Circular Quay, Sonoma "was greatly admired" (Daily Telegraph). On 20 February 1901 she entered Mort's Dry Dock for cleaning and painting of her hull. Starting the return portion of her maiden voyage, Sonoma sailed on the 26th for Auckland at 2:00 p.m.and, after "a fair trip across," docked there the morning of 2 March and sailed later that afternoon.

|

| 'Frisco-bound, Sonoma sails from Auckland. Credit: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19010308-6-1 8 March 1901 Auckland Weekly News. |

After calling at Pago Pago on 5 March 1901, Sonoma bucked exceptionally strong trade winds and a rough sea and made Honolulu on the 12th. Concluding what had been as successful a maiden voyage as any vessel would wish for, Sonoma came into the Golden Gate on the 18th, doing the passage from Honolulu in 5 days days 11 hours 22 minutes. She landed 144 First, 54 Second and 49 steerage passengers at San Francisco.

|

| Busy days at Cramp's: construction of the Imperial Russian Navy cruiser Retvizan (foreground) with Ventura fitting out in the background. Credit: U.S. Library of Congress. |

|

| Ventura ready for her trials (note her hull is entirely painted black with no wide white top strake) with the four-funnelled Retvizan on the left. Credit: The Times (Philadelphia), 10 December 1900. |

Meanwhile, the third sister, Ventura, with the attendant diminished fanfare afforded the third of any trio, was finally completed and ran her trials before the end of 1900. Although it was originally announced she would run her tests on 6 December, these were postponed at the last minute to the 19th. Then fog caused another 48-hour delay and she finally underwent her trials on the 22nd under Capt. Radford Sargent with Edwin S. Cramp aboard representing the builders. "In her trial performance the Ventura fulfilled every stipulation of the contract, including a speed of seventeen knots an hour. Four runs were made between the lightships outside of the Delaware Capes, after which a straightaway run of eight hours was made to seaward." (Philadelphia Inquirer). She return to Cramps at 8:30 a.m. on the 24th.

Leaving Philadelphia for San Francisco on 29 December 1900 (and scheduled to arrive on 6 February 1901), Ventura (Capt. W. Hayward) capped off a remarkable output for the year for Delaware River shipyards, no fewer than 77 vessels having been turned out and of the 180 American ships over 1,000 gross tons at the time, 160 were Delaware River-built.

The Ventura will have the advantage of the experience gained by the mistake made in sending the others off before they were ready and should be in first class condition when she leaves.

Honolulu Republican, 11 January 1901

Captain Hayward, who superintended the building of all three vessels, is in command of the Ventura, and as the defects in the Sierra and Sonoma have been rectified in Ventura the supposition is that she will beat the 'record' made by the Sonoma.

San Francisco Examiner, 6 February 1901

Alas, as if in defiance of the press predictions, Ventura's delivery voyage was more than star-crossed and the defects and inconveniences experienced in her sisters assumed tragic proportions before it was over. On second day out she was hit by a heavy storm which carried away a portion of her starboard rail, stove in a lifeboat and smashed several ladders. Then, one day after leaving Valparaiso, on 23 January 1901, the main steam pipe of the port boilers exploded, instantly killing five men and scalding another five. The details of the accidents awaited the vessel's arrival at San Francisco on 7 February:

|

| Credit: San Francisco Chronicle, 8 February 1901. |

The maiden voyage of the steamer Ventura, which arrived her from Philadelphia this morning, was a very sad one. With more than one-half the distance covered, and with everything in favor of the pleasant and record breaking trip, in an instant all were plunged into deepest gloom. The main steam pipe of the port engine burst and five men were instantly killed and five others badly scalded.

The accident occurred at 6:15 o'clock on the night of January 23rd, the day after the vessel sailed from Valparaiso. The Ventura was then in latitude 30.42 degrees west. The evening was pleasant and those who were not on duty were enjoying the privilege of the deck. Suddenly a terrific explosion was heard and vessel shook violently. Everybody was certain that one of the boilers had burst and expected to see the ship settle.

Chief Engineer Haynes made for engine-room, his first assistant at his heels, and down the ladders went swarming oilers, firemen and coal-passers, who had relieved from duty only a short time before. The engine, boiler and firerooms were filled with vapor and the hissing of escaping steam almost drowned the agonizing cries of injured men. When the steam lifted, a fearful sight met the gaze of those who had rushed into the engine-room. Lying on the floor in positions indicating acute pain were ten bodies. Five were dead, but the rescuers did not know it at the time. Up the narrow ladders to the main deck the unfortunate men were carried, the Ventura meanwhile having been stopped. The bodies were laid out, the dead being quickly covered, the injured receiving the quickest possible attention.

Next day at noon the bodies of the dead were consigned to the sea, Captain Hayward reading the burial service over them. The dead were: Jr. Engineer George W. Robb (26) Fireman William Faren (39), Fireman J. Desmond (26), Coal passer Paul Beier (26), Stowaway Felix Glass (19).

San Francisco Examiner, 8 February 1901

With the four port boilers now disabled, Ventura resumed passage on her remaining four starboard boilers and engine to reach San Francisco almost on schedule on 7 February 1901, recording 38 days, 23 hours and 50 minutes for the voyage or just 14 hours more than Sonoma. She anchored in Mission Bay and a team from Risdon Iron Works effected repairs and she then shifted to the Sugar Refinery Pier to be readied for her maiden voyage. Unlike her sisters, Ventura was not repainted white and her hull remained black without the white top strake. On the 11th she was docked at the Pacific Street Wharf with the expectation of sailing at 9:00 p.m. on the 13th.