If Mariposa and Monterey of 1956 represented the end, their predecessors Mariposa and Monterey of 1932 represented the acme, the apogee of American liners to the Antipodes. Seldom in the history of steam navigation did a pair of sister ships so immediately dominate an entire route or better fulfill the ambitions of government encouragement of its merchant marine. Of all the splendid liners spawned by the Jones-White Act of 1928-- Mariposa, Monterey and Lurline-- were among the most impressive when introduced and went on to be the most successful and longest lived trio of passenger liners ever built, chalking up an astounding total of 163 years between them, Monterey finally succumbing in 2000 at the age of 68 after more than a half a century of active service.

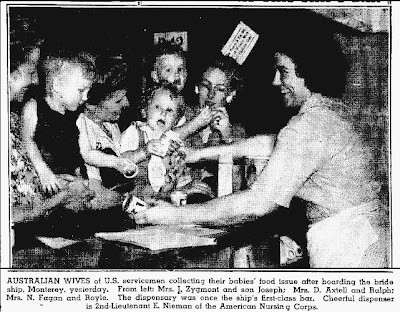

A longevity and legacy too fulsome to be contemplated let alone properly appreciated in a single monograph. So here, the focus will be Mariposa and Monterey's pre-war service on the U.S.-Antipodes route, wartime transport duty and aborted post-war rebuilding. A story of liners in their prime during the 1930s halcyon heyday of ocean travel with its conflicting themes of success, slump and style; valiant and varied war service and post-war limbo. And the Stars and Stripes and United States Mail Flag proudly at the mastheads of the finest pair of sister ships ever to trade Beneath the Southern Cross.

Three years ago when we decided to build these ships, we had great faith in the future of trade between California and the Antipodes, and so did the United States Shipping Board and the Post Office Department, which have aided in their construction. Unless we had such confidence we certainly would not have begun such a comprehensive program and we have just as much confidence that Australia and New Zealand will be first to lead the Pacific area out of the present economic depression. The Matson company is ready to put all its resources and effort to make this venture a success.

Edward D. Tenney, Chairman, Matson Navigation Co., 4 February 1932

It was an uniquely American beginning to the oldest of all U.S.-flag shipping companies-- a confluence of one of the most famous and successful magnates and empire builders, a German immigrant named Claus Spreckels, and an obscure Swedish immigrant seafarer, Capt.William Matson-- and of two shipping enterprises, both begun remarkably in the same year, 1882, which would link Hawaii, the islands of the South Pacific and the Antipodes with the boundless and buoyant America of the Gilded Age.

One of America's great merchant adventurers, empire builders and developers… of communities, industry and commerce... Claus Spreckels (1828-1908) was the quintessential American success story. In 1846, he emigrated from Germany to America, first New York City and then San Francisco and from running a grocery store to a brewery to resorts and sugar beet refineries. By 1876 he set his entrepreneur vigor to the Kingdom of Hawaii which had signed a Reciprocity Treaty with the United States the previous year, removing duty on sugar imports and opening up commerce between the two. In 1878 Spreckels founded Spreckelsville, a company town on Maui which became the largest sugarcane producer in the world.

|

| A Dynasty of Destiny: Claus Spreckels (1828-1908) (left) and his son John D. Spreckels (1853-1926). |

Matching his father in business acumen, the eldest of Claus Spreckels' five children, John D. Spreckels (1853-1926), started J.D. Spreckels & Bros. in 1880 which concerned itself with the refining, transport and distribution of Hawaiian sugar. With shipping services from Hawaii to California wholly inadequate, the Spreckels set their sights on starting their own line. On 23 December 1881 the Oceanic Steamship Co. was incorporated in San Francisco with a capital stock of $2.5 mn. and began regular San Francisco sailings with the chartered British steamer Suez in June 1882.

There was business enough to share with a Capt. William Matson (1849-1917) who was a Swedish emigrant seafarer and captain of Spreckel's yacht Lurline. The two established a friendship and Spreckels bought shares to finance Matson's first vessel in 1882, the 195-ton schooner Emma Claudina, named after Spreckel's daughter, which made her first voyage under the Oceanic houseflag in April. Thereafter, Oceanic and Matson cooperated fully and came to dominate the island trade.

Spreckels lost little time in ordering its own tonnage and in 1883 two new steamers, the 3,158-grt, 14-knot Alameda and Mariposa, were built by Wm. Cramp. Far wider horizons beckoned when, in 1885 Pacific Mail Steamship Co. relinquished its Australian mail contract which Oceanic together with the Union Steamship Co. of New Zealand now shared, securing a three-year contract with both Australia and New Zealand for a four-weekly service from San Francisco, Honolulu, Pago Pago, Auckland and Sydney, effective in November. Alameda and Mariposa were assigned to this and Oceania acquired Pacific Mail's Australia and Zealandia to replace them on the direct Honolulu run and they were uniquely registered in Hawaii.

Proving the obverse of the "trade follows flag" imperial credo, Spreckels and other American business interests so wedded the fortunes of Hawaii to the United States that in the wake of the Spanish American war of 1898 that suddenly made America a Pacific power, it was no surprise when Hawaii, too, was annexed, becoming an American Territory in 1900. It was the beginning of a new American century in the Pacific. The Hawaiian-Mainland run became a protected domestic sea route excluded to foreign tonnage, ending Oceanic's partnership with Union Steamship Co. and creating Matson Navigation Co. in 1901 with the acquisition of its first passenger steamer for the Hawaii-Mainland route.

In a bold stroke even for the Spreckels, three new express liners-- the 17-knot, 6,000-ton Sierra, Sonoma and Ventura were ordered from Wm. Cramp and commissioned in 1900 for the San Francisco-Antipodes via Hawaii service. The trio quickly established themselves supreme on the route, Sierra setting a new San Francisco to Sydney record of 19 days 7 hours. More than just dominating the North America-Antipodes run, Oceanic was now a major competitor on the U.K. to Australia route, offering a London-Sydney journey via express Atlantic liner to New York and transcontinental railroad to San Francisco of 33 days versus 40 via Suez or the Cape.

|

| U.S.M.S. Ventura, after her 1912 rebuilding and resumption of the Oceanic service which she and her two sisters would maintain for another two decades. |

The calamity of the San Francisco earthquake and fire in April 1906 followed by the financial Panic of 1907 rocked even the fortunes of the Spreckels who found it impossible to make up the losses on the post-fire disrupted Oceanic service without an increase in the mail subsidy which was not forthcoming. In the first of two such prolonged disruptions, the Antipodes service ended in 1907, the three ships laid up (Sierra, however, successfully running on the Hawaii run 1910-15) until 1912 when Congress renewed the mail contract under better terms and the trio refitted and converted to oil fuel, but running only to Australia as The Sydney Short Line maintaining a 30-day London-Sydney journey time. Sierra, Sonoma and Ventura soldiered on for some three decades, outliving more than a few efforts to replace them and sailing on while American-flag competition on other of the world's ocean highways all but disappeared.

American merchant marine policy foundered after the First World War, the wartime created U.S. Shipping Board's government funded output of an armada of wartime-built "standard" designs, most of which were not even completed until hostilities had ended, had little peacetime commercial utility amid a glut of tonnage, high tariffs and inflation dragging down global trade.

Moreover, the mail contracts left over from the 1891 Ocean Mail Act, were all due to expire and that in particular granted to Oceanic Steamship in 1912, set to end on 30 June 1922. The Merchant Marine Act of 1920 did authorize the Post Office to extend existing mail contracts and increase the per mile payment. This was effected in 1922 with Oceanic securing the first of a series of two-year extensions paying $3 per ocean mile.

There was a brief flurry of speculation that Oceanic might get from the U.S. Shipping Board the former N.D.L. Prinz Ethel Friedrich, which was seized in the First World War and operated as the transport U.S.S. De Kalb, but she went instead to United American Lines as Mount Clay.

|

| Profile of the proposed Oceanic S.S. pair for the Antipodes route c. 1923. They would have been the first American turbo-electric liners. |

The June 1923 issue of Pacific Marine Review reported that Oceanic Steamship Co. was "discussing plans for the construction of two new passenger steamers to operate in the San Francisco-Sydney mail and passenger service. It is reported that the vessels will be equipped with turbo-electric engines capable of developing speed of 18 knots. Accommodations for 220 First and 120 Second Class passengers will be provided." A one-year extension of the main contract was signed and speculation continued that if the new ships were contracted, they would qualify for the higher $4 a mile rate.

In the event, the pair were never ordered as the 1920 Merchant Marine Act lacked the commitment to new long-term mail contracts or low rate loans to facilitate newbuildings. Instead, Oceanic repurchased the 24-year-old Sierra (which had operated as the Polish flag emigrant liner Gdansk since 1919) in December 1923 and after refitting, she rejoined her sisters on the Antipodes run. That proved to be the final capital investment by the Spreckels organization in what remained a money losing proposition (to the tune of $3.5 mn. in losses) even in boom times. It was not surprising when Oceanic Steamship Co. was put up for sale and on 21 April 1926 it was quickly purchased by Matson Navigation Co. for $1.5 mn. Matson had the capital and the confidence that evolving new merchant marine legislation would finally enable meaningful renewal and expansion.

So it was that Matson inherited the operations and the quarter of a century old Sierra, Sonoma, Ventura trio of what was now called The Oceanic Steamship Co. and run as a fully owned subsidiary. While benefiting from Matson's enviable public relations, sales and agency operations, it was but a holding operation awaiting the passage of the most significant piece of Merchant Marine legislation to date: The Merchant Marine Act (or Jones-White Act after its two originators, Sen. Wesley L. Jones (Washington, Republican) and Sen. Wallace H. White (Maine, Republican) of 1928.

The legislation increased the per mile payment of mail contracts which were let for a ten-year period on designated overseas routes and established a newbuilding fund of $250 mn. from which low interest loans up to three-quarters the cost of new ships were awarded on the proviso ships were built to U.S. Navy specifications with potential wartime use in mind. The Jones-White Act transformed the American passenger fleet and vastly increased its presence, power and prestige on the world's ocean routes. And no single American steamship company was better poised to take immediate advantage of the new order than Matson-Oceanic.

In April 1928 Pacific Marine Review reported that Matson-Oceanic was planning three new combination passenger and freight liners, costing upwards of $5 mn. each, for the Antipodes run, carrying 350 First and 250 Second Class passengers and 7,000 tons of cargo. "W.P. Roth said the construction program was contingent upon the passage by Congress of the White Bill. To quote Mr. Roth these vessels will be built 'if the White Bill passes enabling the government to lend us money. Under the provisions of this bill, we would be granted a subsidy or given a mail contract to run not less than ten or more than twenty years.'" The legislation, passed by the U.S. Senate by a vote of 53 to 31 (ironically, far more Republicans voted against it than did Democrats), was signed into law by President Coolidge on 23 May.

The United States Post Office on 19 October 1928 inked a new 10-year mail contract for route no. 24 San Francisco-Antipodes which obligated Matson-Oceanic place into service one new vessel within three years and a second within four.

The U.S. Shipping Board approved on 17 October 1929 a loan of $11,780,000 ($5,850,000 for the first ship and $5,827,000 for the second) to Matson-Oceanic to construct two new ships to replace Sierra, Sonoma and Ventura. With advance plans already well in hand and approved by the U.S. Navy, no time was lost in contracting the new vessels. On the 25th the order was placed with Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corp. at its Fore River, Quincy, Massachusetts yards. Their initial specifications were cited as being 20,000-25,000 grt, length of 620 ft. and service speed of 20 knots with accommodation for 620 First and 217 Tourist Class. As such, they were only slightly smaller than the new Dollar Line sister ships under construction at Newport News.

|

| Early rigging plan and profile for the new Matson-Oceanic ships. Credit: Pacific Marine Review, December 1929. |

On 17 November 1928 Matson's Vice President A.C. Diericx announced: "The designs for the Matson Navigation Company's new Australian liners have been approved by the Navy Department and the United States Shipping Board. The vessels will rated in Class 2 under the Jones-White bill, and will be capable of a sustained sea speed of twenty knots. These liners will mark the first step of our company to revive the American merchant marine on the Pacific with Government aid under the new law."

|

| First artists rendering of the new ships showing them in dark hulls. Credit: Honolulu Advertiser, 20 May 1931. |

Assigned yard nos. 1440 and 1441, construction of the first hull commenced with an impressive and symbolic keel laying ceremony at 2:00 p.m. on 17 May 1930. Lt. Gov. Youngman of Massachusetts drove in the first rivet which was made of Swedish iron salvaged from U.S.S. Constitution during her recent rebuilding and restoration, and one of the four that were made and silver plated for the occasion, two others being used in the keels of her sisters Present for the event were Rep. Wallace White, Chairman of the U.S. House Committee on Marine and Fisheries and one of the co-authors of the Jones-White Act, and U.S. Postmaster Walter F. Brown. The keel of the second ship, yard no. 1441, was laid down on the adjacent slipway at Fore River on 13 June.

|

| The keel laying of the first of the Matson liners was "news" along all of their route as this photo in the Sydney Morning Herald of 9 July 1930 indicates. |

|

| The Honolulu Star Bulletin of 20 May 1930 used this unusual rendering of the new Matson-Oceanic liner to report on her keel laying. Note the different open promenades and the double-banked lifeboats. |

Events moved quickly and on 5 September 1930 Matson-Oceanic exercised an option for a third ship (yard no. 1447 which would be completed for the company's non-subsidised Hawaii run as a running mate for Malolo) by which time the keel of no. 1441 was laid on the adjacent slipway to no. 1440. Four days later it was announced that the first two ships would be named Mariposa and Monterey respectively, this following Oceanic's practice of naming ships after California counties. Conversely, the name of the third ship, a true Matson liner, was revealed to be Lurline on 15 January 1931 and following its naming practice.

|

| One of four paintings of the new ship by Duncan Gleason completed in October 1930 still showing the ship in the seal brown hull. |

If the new ships' names were an appreciative nod to Oceanic traditions, the announcement by E.D. Tenney, Chairman of the Board, on 5 March 1931, during a visit to the Port of Wilmington that the first would be registered in Los Angeles rather than the customary San Francisco, was in recognition of the now Matson-owned Los Angeles Steamship Co.. "Tenney states that several officials of the Matson company shortly will recommend that the Mariposa be registered at this ports, intimating there is little likelihood the plan will miscarry. The action the veteran shipping man said, is a gesture of friendliness to this port and an indication the company means business here indefinitely and will lean heavily on Southern California business… Registration of the ship here will add notably to the port's prestige and boost the tonnage of ships making it a home port." (The Long Beach Sun, 6 March 1931).

On 4 May 1931 Matson announced that Mariposa would be launched on 18 July, christened by Mrs. Wallace Alexander, wife of the Matson Vice President. Four days later the San Francisco Examiner predicted that Capt. Joseph H. Trask would be appointed her master, it being said it was "toss-up" between him and Capt. Berndtson, master of Malolo. By coincidence, Capt. Trask arrived in Sydney on 30 April in command of Sierra, completing his 300th voyage on the San Francisco-Antipodes run.

The addition of Los Angeles and Auckland to the Antipodes run was confirmed on 18 May 1931 effective with Sonoma on 2 July from San Francisco. It marked the resumption of the original Auckland call that ended in 1907 while the Los Angeles stop reflected Matson's increasing commitment to the booming Southern California citrus trade as well as the connections already established with the acquisition of the Los Angeles Steamship Co. (LAASCo) that January which operated their own service to Hawaii from the port.

It is significant that these huge new American flag vessels, like many others now building or contracted for, are pointed for service in the Pacific. Recent years have seen the development of new world currents in foreign trade and travel indicating that the 'Pacific Era' is at hand. In American ships alone, upwards of $65,000,000 worth of new tonnage is building for this trade.

San Francisco Examiner, 30 June 1931

On 29 June 1931 Matson-Oceanic set final plans for Mariposa's launching for 15 July, it being stated that "water from the picturesque landlocked harbor at Sydney, Antipodean terminus for the big liner will be used in the christening." Prohibition, of course, not waived even for ocean liner christenings. The launch of Monterey was set for 10 October. In consideration of the hull's size, the Fore River was closed to all shipping after 10:30 a.m. that day and it was estimated that the hull would throw a 14-foot wave on entry and would almost reach the Weymouth shore opposite until the checking chains held her, the hull being 631 ft. in length and the channel about 800 ft. wide.

|

| Mrs. Mary S. Alexander, wife of Matson Vice President Wallace M. Alexander, Godmother of Mariposa, Credit: Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection. |

What was then the largest passenger ship ever built in New England was christened Mariposa by Mrs. Mary S. Alexander and sent down the ways before a crowd of several thousands at 1:30 p.m. on 15 July 1931. Among the dignitaries present were W.G. Race, President of Bethlehem Steel Corp and Albert H. Denton, Shipping Board Commissioner.

Water from the harbor of Sydney, Australia, dashed against the towering white bow of the Matson Navigation Company's liner Mariposa this afternoon, and the largest ship ever constructed in a New England shipyard slid down the ways of the Fore River shipyards-- first of a trio of Matson superliners building at Fore River.

Shooting down the greased ways with increasing momentum, the ship sent a great wave rushing toward the Weymouth shore before the series of intricate stops checked her speed. She settled in the water without a hitch, amid the blare of whistles and the flare of music, while a large gathering of distinguished guests cheered.

Mrs. Wallace M. Alexander, wife of a Matson vice president, was the sponsor of the ship, and broke the bottle of Australian water on the hull as the signal for the release of the skids. W.P. Roth, president of the Matson Navigation Company, by her side on the decorated platform, gave the word that all was ready for the launching. Ernest Lee Jahncke, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, was one of the guests."

Boston Globe, 18 July 1931

For over three centuries Massachusetts has played a prominent part in the building of ships. We may rightly refer to this State as "Maritime Massachusetts".

On Oct. 21., 1797, there launched from the ways of Hart's Shipyard, in Boston, America's most famous naval vessel, the Constitution, popularly known as 'Old Ironsides".

We have just witnessed the launching of the Mariposa, a new unit soon to be added to America's merchant marine. This ship has distinction of being the largest commercial vessel constructed in this historic maritime State.

"It is of considerable interest that the first rivet driven in this ship was taken from the original iron used in the construction of the Constitution."

It is through the constructive shipping legislation passed by the Seventieth Congress that ship owners in the United States are enabled to build such ships in American yards as the one launched today.

Not only shipbuilding but industry throughout the entire country has benefited in the building of these new ships."

S.S. Sandberg, Commissioner of the U.S. Shipping Board

|

| The Honolulu Star-Bulletin of 3 August 1931 used this splendid photo to report on the launch of Mariposa. |

Early into her fitting out, Mariposa's fore deck was used on 24 July 1931 as the background for the filming of a scene of "Rich Man's Folly" (Paramount) with George Bancroft.

Having already established itself in the long cruise trade with Malolo's annual long Pacific trips since 1929, Matson announced on 25 September 1931 an equally ambitious delivery/maiden cruise for Mariposa, from New York on 16 January 1932 for San Francisco via Havana and Los Angeles (arr 29th) and San Francisco on the 30th. On 1 February she would depart on a 30,000-mile, 19-port, 14-country cruise on a reverse itinerary to Malolo's third Pacific cruise which had just commenced, calling at Hawaii, South Sea islands, Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea, Java, Malaya, Siam, Philippine Islands, China and Japan. On 28 April she would make her first regular voyage from San Francisco to the Antipodes.

|

| Mariposa fitting out at Fore River. Credit: Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 3 October 1931 |

Capt. J.H. Trask brought Sierra into San Francisco on 7 October 1931 for the last time, having joined the ship when she came new out of Cramp's shipyard 31 years previously, and, after a spell of leave, headed east to assume command of Mariposa.

The keel of the third new Matson liner was laid down at Fore River on 3 October and seven days later the second, Monterey, was launched by Mrs. E. Faxon Bishop of Honolulu at 9:20 a.m. "Amid the cheers of more than 5,000 spectators the $8,000,000 steamer Monterey slid gracefully down the ways at the Fore River yards of Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation here today to join her sister ship, the Mariposa, on the high seas." (Los Angeles Times, 11 October 1931).

|

| Credit: Napa Journal, 23 October 1931. |

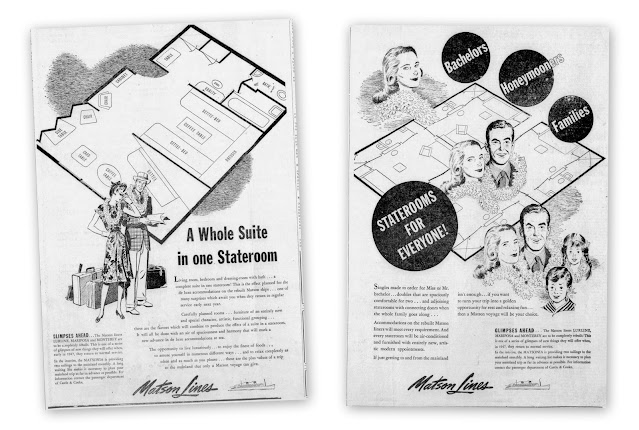

Already one of the first American lines to really embrace modern publicity and advertising, and doubly important in attracting Depression diminished business, Matson-Oceanic placed six full pages of advertising for Mariposa's maiden cruise in the 24 October 1931 issue of the Saturday Evening Post.

|

| The Fore River fitting out basin in November 1931: Monterey (left) and ready for her trials, Mariposa (right). Credit: Warren Parker photograph, digitalcommonwealth.org |

|

| The completed Mariposa at Fore River. Credit: William B. Taylor photograph, Mariners Museum. |

On 8 November 1931, Mariposa's trials were set for the following month and all was proceeding exactly on schedule. She left Quincy for the first time at 7:28 a.m. on the 23rd, commanded by Capt. Joseph I. Kemp (still being of course owned and manned by Bethlehem Shipbuilding) and sailed to South Boston where just before noon she was floated into the Commonwealth Dry Dock for cleaning and painting of her underwater hull prior to trials.

Mariposa left dry dock on 26 November 1931 and the following morning sailed from South Boston at 8:00 a.m. for a shakedown run for her builders. Passing Deer Island Light at 8:35 a.m., she passed out into the Bay where, after working up, she returned that evening to Quincy for final adjustments and fitting out. Destined for more tests, Mariposa departed the morning of 5 December for a series of runs in the Bay between Cape Ann and Cape Cod after which she returned to Fore River.

|

| Picture Perfect: U.S.M.S. Mariposa berthed at Quincy, Massachusetts, November-December 1931. Credit: Warren S. Parker photograph, digitalcommonwealth.org |

On 9 December 1931, Mariposa left Fore River at 9:00 a.m. and "pushed her way up the coast in a blinding snowstorm today and was safely at anchor outside of Rockland breakwater early tonight." (Boston Globe, 10 December 1931). Commanded by Bethlehem's Capt. Joseph I. Kemp, she had aboard 150 experts and specialists to oversee every aspect of her machinery. Matson Vice President Albert C. Dieriex was also aboard as was Charles D. Wetmore, who designed her interiors.

Mariposa's official trials (or in U.S. Navy parlance, standardization trails) were run on the Navy's Rockland course on 10 December 1931. The results were relayed by wireless message by Vice President Dieriex to Matson President W.P. Roth, in San Francisco:

Just finished highly satisfactory trials over naval course, Rockland, with clear weather and wind varying between 15 and 35 miles. Highest single run, 22:843 knots, with developed shaft horsepower of 28,270. Mean of three such runs, 22:274 knots with corresponding mean power of 28,320. Draft 25 feet six inches displacement. Results materially exceed contract requirement and your wishes have been fully met.

|

| Another view of Mariposa at full speed on trials. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

Overnight, she ran her 12-hour economy trials returning to Quincy where she docked at 11:20 a.m. on 11 December 1931. "The Mariposa was designed to meet typhoon weather in the South Pacific seas and she rode the North Atlantic waves with ease," reported the Boston Globe, whilst adding that "Having bettered her contract speed by fully two knots, the Matson liner Mariposa returned to Fore River yesterday from the Rockland, Me., course with brooms lashed to the mastheads." Matson-Oceanic accepted delivery of its finest and largest vessel from her builders on the 14th.

|

| Mariposa at Fore River. Credit: Mariner's Museum. |

Bidding farewell to the river of her birth, Mariposa left Fore River on the flood tide of the afternoon of 9 January 1932. "As the massive white steamship passed through the draw of the Fore River Bridge and turned slowly down the hairpin curve in the channel of the river she got a great sendoff from other steam craft at the yard and in the river." (Boston Globe 9 January 1932). As soon as she cleared Quincy, Capt. Kemp turned over command to Capt. Harry Trask and Mariposa headed south with 65 passengers, all invited guests. Leaving Boston at 10:00 a.m. on the following morning, she hit heavy weather, including a full gale but according to her skipper, "she rode the storm with little rolling and no vibration." On the 10th, Mariposa docked at Bush Terminal, Pier 2, South Brooklyn, to load cargo and then shifted to Pier 86 North River where she was opened to invited guests and later the general public for inspection from 13-15th.

A new era of American supremacy of the South Pacific Ocean Highway was in the offing.

|

| Credit: Huntington Museum. |

New Sovereigns of the Pacific, Matson-Oceanic brochure, 1932.

Matson-Oceanic's Mariposa, Monterey and Lurline are, by any standard, the most successful trio of ocean liners ever built and as such, surely the greatest American passenger liners of all time. When new, they were the acme of modern liner design and construction, even more so when compared to their immediate predecessors Sierra, Sonoma and Ventura; they were two generations apart and seldom did replacements be more different, indeed of another era and quality entirely. Coming at the very end of that truly epic production of wonderful ships of the Jones-White Act of 1928, they capped a new era of American innovation and excellence in shipbuilding, marine engineering, decoration and indeed style. Mariposa and Monterey literally swept the seas of competition and no two ships more dominated their route more quickly and more definitively.

|

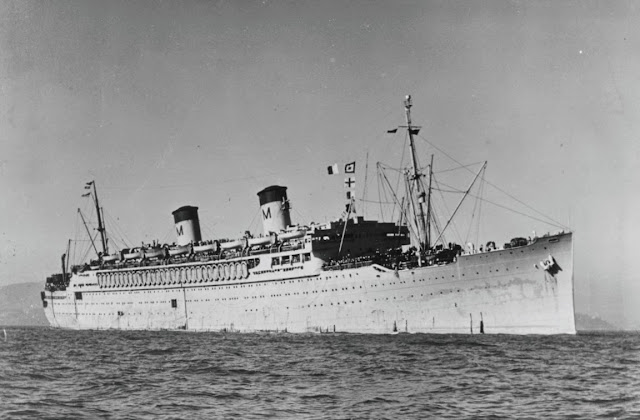

| New Sovereign of the Pacific: U.S.M.S. Mariposa on trials. Credit: Matson Line photograph. |

|

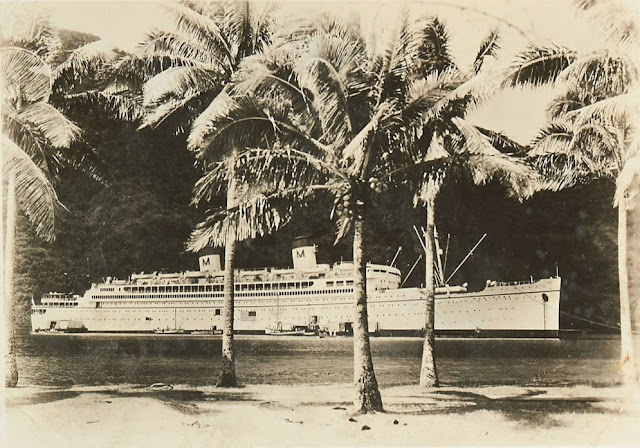

| No less impressive at anchor (Sydney Harbour on her maiden arrival), Monterey looking every inch the robust Tasman taming Yankee she was. Credit: National Library of Australia, Fairfax Collection. |

One hundred sixty-three combined years afloat: several factors contributed to the Matson-Oceanic Trio's remarkable longevity. Their size and speed were optimal for many routes and purposes, their construction and build was extremely robust ("overengineered and overbuilt" to naval specifications), their machinery was conventional, resisting turbo-electric alternatives that seldom stood the test of time or economics, their layout was essentially one-class with but one other, high quality "second class" enabling a straight forward arrangement in a very large superstructure while the good cargo capacity did not impact the passenger areas. In service, they proved good seaboats and economic steamers and singularly free of defects or design flaws. And throughout their Matson careers, they were afforded the meticulous maintenance that was and remains a hallmark of the line. Their quality too, was appreciated and cherished by succeeding generations of owners, officers, crews and passengers, furthering their legacy and longevity.

|

| Left: Matson President W.P. Roth and, right: Vice President A.C. Diericx |

Electing not to return to William Francis Gibbs (designer of Malolo), Matson-Oceanic entrusted the design of the new ships to Bethlehem Shipbuilding's house architect Hugo P. Frear (1862-1955), John F. Metten, Marine Engineer, and their own Vice President, A.C. Diericx (1866-1942), an accomplished naval architect in his own right and designer of Matsonia and Manoa of 1913.

Under the provisions of the Jones-White Act, the design and specification of the new ships had to be vetted and approved by the U.S. Navy with potential wartime service in mind as a fast transport or auxiliary cruiser as had been Malolo. This was reflected in the hull subdivision being to excess of the requirements of the 1929 Convention for Safety of Life at Sea, especially in regards to stability in a damaged condition, steering gear entirely below the waterline and provision for gun mountings. With both the requirements of the U.S. Navy and those of Matson-Oceanic, their bunker capacity of 6,606 tons was sufficient for a round trip between San Francisco and New Zealand without refueling.

Identical sister ships, their principle dimensions were 18,017 tons (gross American measurement), 26,141 tons (displacement, 10,580 (net), 632 ft. (length overall), 605 ft. (length b.p.) and 79.4 ft. (beam).

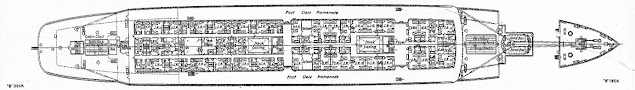

Of the ships' nine decks-- Bridge, Boat, A, B, C, D, E, F, G-- four were entirely for passengers. The hull was divided into 13 main compartments by 12 watertight bulkheads. E Deck was devoted to crew, dining rooms and galleys with passenger accommodation on D, C, B Decks with the main public rooms on A Deck. On Boat Deck was the bridge, officers quarters and mess rooms as well as the gymnasium and sauna, open promenades and an impressive deck tennis court atop the raised house of the main lounge amidships between the two funnels and another sports deck aft.

...and the whole appearance of the ship is of dignity and neatness, with a very jaunty and lively sheer and a curved stem suggestive of the modern cruiser yacht profile.

Pacific Marine Review, February 1932

"Yankee Built": if any ships could be described as reflecting their country of design and build, Mariposa and Monterey were quintessentially American in their broad shouldered, businesslike manner with a tremendous amount of freeboard, slab sided, beamy and full bodied underwater. Yet, they were, at the same time, remarkably graceful, pleasingly profiled and handsome ships with probably the best transition between hull and superstructure of any passenger liner of their age. The appearance of speed and modernity was imparted by a novel and subtle refinement that they, in fact, introduced: the second funnel being slightly shorter than the first, imparting a "streamlined" effect oft credited to Normandie, but pioneered by the American trio three years earlier.

|

| Bathed in New Zealand sunlight, an immaculate Monterey shows her pleasing lines to advantage. Credit: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 5-U12 |

|

| Impressive bows with slightly raked knife-edge stem, very high freeboard and high slab sides with no tumblehome are characteristic features illustrated above. |

|

| Smokestack Studies: showing the substantial cowled tops and the single chime steam whistle and Typhon siren. Credit: Johan Hagemeyer photographs, mutualart.com |

The funnels themselves were of a short, beefy profile and like many American liners of the day fitted with pronounced "Admiralty caps" which anticipated in appearance those fitted on the wartime "Liberty" ships and T-2 class tankers. Their effectiveness in keeping smoke and smuts clear of the ship was somewhat suspect given that Mariposa was first delivered with her substantial engine room blower vents aft of the second funnel, aft king posts and mainmast painted buff which were repainted black after her first voyage!

In service, Mariposa and Monterey proved ideal for their route, their high freeboard and flared bows making them remarkably dry ships in the oft-encountered headseas and rollers of the notorious Tasman although they could roll in the beam seas often encountered in those waters, but nothing like Malolo or "Marollo" as she infamously known. One quality of these ships was their astonishing clean entry at speed, no large and fast liners cleaved the seas with nary a ripple or foam as did Mariposa and Monterey. They were also renown for the lack of vibration, shuddering and creaking at speed. For insulation purposes, the whole of the hull in way of the accommodation was lined with cork slabs behind the panelling.

The ship is built without the use of expansion joints, B deck being the strength deck amidships and C and D decks at the ends. To distribute properly the stresses at the forward end of the deck house, B deck is continued forward of the house for a considerable distance and the side plating is carried up to that deck, and special attention is given the continuity of structure between B and C decks. Aft, the erections end more gradually, and the strength is thus more easily transferred from B deck to C deck, and then to D deck, way aft. Over the greater part of the ship's length, the heavy side plating is carried up to B deck.

Pacific Marine Review, February 1932

Finally, and most wonderfully, was their unmatched staunch Yankee-built qualities which ensured Monterey a place in the annals of large passenger liners with an astonishing 68 years at sea with her completely original hull, machinery and boilers. She and Mariposa remain enduring exemplars of American shipbuilding and define "Bethlehem Built" when that meant something.

Their appearance was abetted by the new Matson-Oceanic colors, introduced in 1931, by Malolo, of all white hull, blue sheer line, green boot topping and buff masts, funnels and exterior facings of the Boat Deck houses and forward well deck. Originally, renderings of the ships showed them in the traditional seal brown hulls. Then there was the question of... the "M"s. This is the source of considerable confusion. When Matson acquired Oceanic, Sierra, Sonoma and Ventura were given their funnel colors and big welded "M"s on their single funnels, but painted the same buff as the stack, and with black not blue upper band. Yet, Mariposa made her delivery and maiden cruise in full Matson livery. By the time she returned to San Francisco, Matson had settled on a revised funnel color for Oceanic and Los Angeles Steamship Co. that was the same as their ships but sans "M"s. Mariposa's were removed before she sailed, under the Oceanic S.S. Co. houseflag on her first regular mailship voyage to the Antipodes. Monterey never had "M"s initially. Both ships eventually had "M"s placed on their funnels in August 1939 when Matson paid off the last of their original construction loan.

|

| The forecastle showing the no. 2 hold. Credit: Pacific Marine Review |

The cargo capacity was substantial with a total deadweight of 5,000 tons (bale) and 850 tons (reefer) in six holds of 245,019 cu. ft., 34,629 cu. ft. reefer and 29,974 cu. ft. baggage and mail. There were two holds forward with no. 2 hold hatch used as the First Class swimming pool tank and one hold aft which was similarly arranged to serve as the Cabin Class pool. These were worked on the foremast, four booms of 5-tons capacity each and one of 30-tons capacity; on the mainmast, two of 5-tons capacity each; on the forward end of the deck house two 5-ton booms; on the two kingposts aft, one 5-ton boom each. Additionally side ports were fore and aft for regular and reefer cargo.

|

| The wheelhouse. Credit: Pacific Marine Review |

The behavior of the Steamship Mariposa on her trials and on her maiden trip to New York leaves no doubt as to the comfort of the passengers; and an examination of the excellent results obtained on the measured mile trials held at Rockland, together with the consumption figures from the economy run, demonstrate that this vessel has established new high standards for efficiency among vessels of her size and type and justify very definitely the choice of hull form and type of propulsion.

Pacific Marine Review, February 1932

|

| Engine room control station. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

Although the proposed pair of newbuildings for Oceanic c. 1923 would have been the first American turbo-electric liners and the propulsion was certainly readily embraced by many of the Jones-White Act ships (notably Morro Castle/Oriente and President Hoover/President Coolidge), it is telling that the last big express liners built under the Act-- Manhattan/Washington and Mariposa/Monterey/Lurline-- reverted to conventional geared turbine machinery.

|

| Fireroom. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

Mariposa and Monterey were propelled by twin screws, each driven through single reduction gearing by a Bethlehem impulse-reaction type three-stage turbine. Steam was generated in twelve Babcock & Wilcox water-tube boilers with a working pressure of 375 psi and a total temperature of 640 degrees F.. and operating under forced draft. The oil bunker capacity of 6,300 tons gave a steaming radius of 20,000 nautical miles. The normal sea speed of 20.5 knots was obtained from 20,000 shp and as true sister ships, there was little difference in their trial speeds and performance:

Full speed trials average Full speed trials maximum

Mariposa 22.274 knots 28,030 shp 131 revs. 22.843 knots 28,270 shp 132 revs.

Monterey 22.26 knots 28,825 shp 132.3 23.003 knots 28,900 shp 132.3 revs.

The machinery plant was extraordinary reliable in service and there was not a single case of a defect or delay in hard steaming on a long and exacting route that saw, in just 50 voyages, 750,000 miles logged. In the end, Monterey went on to log some three million miles or more in a half century of active service.

|

| Turbo-generators. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

The electrical generating plant consisted of four Westinghouse 500-horsepower geared turbo-generators generating 2,600 k/w and a total lighting load of 230 k/w. This was an exceptionally powerful plant for its era and like the turbines and boilers, lasted the life of the vessels.

|

| Looking aft from the bridge. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

The all-metal main lifeboats, carried on Welin-McLachlan type gravity davits, comprised two 26-ft. motor boats (10-person capacity); 14 30-ft. lifeboats (70 persons); and four 26-ft. lifeboats (40 persons). The four 26-foot boats were nested inside four 30-foot boats. In addition, two 20-ft. wooden working boats (18 persons) were carried aft at regular Welin hand-operated quadrant davits. The motor lifeboats had cabins and were equipped with radios.

U.S.M.S. MARIPOSA

Rigging Plan, Profile & General Arrangement Plans

credit: Marine Engineering, courtesy William T. Tilley

(LEFT CLICK on image to view full size scan)

|

| Rigging Plan & Profile |

|

| Boat Deck |

|

| A Deck |

|

| B Deck |

|

| C Deck |

|

| D Deck |

|

| E Deck |

|

| F Deck |

|

| G Deck |

|

| Hold |

|

| American resort hotel at sea: Warren & Wetmore redefined American ocean liner decor with Mariposa and Monterey. |

Mariposa strikes a new note in architecture, color, and furnishings. The keynote of design is simplicity; and beauty is obtained without ornate and elaborate decorations. Heaviness of style has been carefully avoided; the opposite extreme is the rule. Furniture through-out the ship is light in appearance, and therefore cool in effect. Rattan and cane are much used, finished both naturally and in vivid contrasting colors. It is especially notable that heavy appearing hardwood is entirely eliminated from the decorations in the first class quarters, appearing only in the curly mahogany bar counter in the men's club room. Drapes and curtains are entirely omitted in the first class; carved wood grilles in soft tones are substituted for them at windows in public rooms. Mariposa is, in fact, the first passenger ship afloat which has not a single curtain or drapery in any first-class stateroom or public room, excepting the rather necessary stage curtain in the main lounge. The effect of the interior decoration as a whole has been so studied and developed that this omission is an appropriate and pleasant departure from the ordinary.

Pacific Marine Review, February 1932

In the evolution of American liner interior decor, furnishing and architecture, the Matson-Oceanic trio were notable ships being just the second group of ships (after President Hoover and President Coolidge) to embrace contemporary decoration and going an important step further than the Dollar pair, by adopting new concepts and use of colors and materials to achieve the first "resort" themed passenger liners. It marked a complete break from Malolo's rather stodgy ocean liner period interiors by Harry P. Etter.

In entrusting the decoration of the new ships to Warren & Wetmore Architects, Whitney Warren (1864–1943) and Charles D. Wetmore (1866–1941), Matson-Oceanic in aiming for something new was doing so with familiar and trusted hands, the same firm having been responsible for its Royal Hawaiian Hotel (1927), the first resort hotel on Waikiki Beach and other resorts like The Boardmoor, countless hotels, Grand Central Station, New York's Chelsea Piers, etc. in a portfolio without equal in the hotel, resort, terminus and travel genre. All the more remarkable that Mariposa, Monterey and Lurline were, in addition to extensive redecoration of Malolo/Matsonia, their only liner interiors.

|

| Whitney Warren (1864-1943). |

The joiner work was done by Hopeman Bros. of Rochester, New York. The design credo, as described by Pacific Marine Review, was "to produce furnishings of a style appropriate to the service in which the Mariposa is to be used. With service in the tropics in mind, the decorators selected soft, cool colors for the interiors; and the oriental and Chinese Chippendale effects are reminiscent of the South Seas and islands therein to which the ship is designed to sail."

Eschewing heavy drapery, dark woodwork and stuffy upholstery to suit tropical voyaging was not novel, and had already been accomplished with Union's S.S. Co.'s Niagara of 1913, but where Warren and Wetmore broke new ground was the use of colors-- soft greens, yellows, pale blues, soft silver grays and cool clean decking, most of which was rubber in complimentary colours, instead or carpets and rugs. The circulating areas-- passageways, foyers and stairs, were bereft of mouldings and pilasters, the passageway bulkheads uniformly finished in pale French grey with decking in blue and light grey rubber. Staterooms doors were finished in dull silver with pale blue frames and the foyers were in gray-green with complimentary flooring.

The interior decoration and furnishing of Mariposa is without doubt a distinct departure from the conventional style of steamship decoration. Period rooms are entirely lacking, and heavy hardwood finish has given way to painted walls; and draperies and window curtains to wooden grills in the public rooms.

Pacific Marine Review, February 1932

Unique among all the Jones-White Act liners, the decor of the Matson-Oceanic sisters finally elevated and enlivened American passenger liner decor away from the Calvinist conventions of the 1920s.

Accommodating 475 passengers, the First Class of these ships was, by any standard, the finest afloat when they were introduced, and indeed could retain that claim through the decade. It occupied all or most of six decks.

Sun Deck featured, aft of the bridge and officers accommodation, a large gymnasium and "medicinal bath" on either side of the forward funnel casing. Amidships was the raised flat roof of the main lounge atop which were two full sized tennis courts, then open deck space, engineers accommodation and aft a sports deck also arranged on the raised roof of the dance pavilion. Around all of this was open promenade deck under the life boats.

The principal First Class public rooms were on A Deck. The de luxe lanai suites were right forward and then the forward foyer. This and its amidships counterpart (between the lounge and smoking room) had ebony framed Chippendale style furniture with champagne-colored leather upholstery, console tables, mirrors and paintings. In Mariposa, one of the painting was by the well known marine artist M. Dawson depicting a brig in a heavy sea. Each of the main stairways had a lift.

|

| First Class library. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

The library-- port of departure for fascinating mental cruises. More than fifteen hundred volumes to meet the taste of every reader. In fine harmony with the spirit of the room are rare old prints of ships of every period… telling in their gallant lines the history of man's conquest of the sea.

|

| First Class library. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

Flanking the forward funnel casing were the library (port) and writing room (starboard). Panelled in knotty pine, including the ceiling, the library was in "early American style" with rare old prints of sailing ships along the inboard bulkhead and wood grills over the windows facing out to the promenade deck. Deep armchairs in blue morocco were complemented by the deep blue rubber decking with thick carpet runner in the same hue down the center. The indirect lighting ran along the sides in the form of a cornice. Large floor to ceiling bookcases were found on each end.

|

| First Class writing room. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

The writing room-- what letters there are to write between ports-- of days crowded with absorbing episodes. If by chance your thoughts lag, there South Sea mural portraying the lands you visit to stir the muse again, and maps by which you can trace your voyage from beginning to end.

The writing room was one of the more striking rooms with its charts and murals of the Pacific Ocean and ports of calls along the ships' route with a soft ivory color used for the cornices and ceilings and desks in soft old yellow and upholstered fixed swivel seats in green, coral and silver brocade. Here, the window grills were in the Sheraton style.

|

| First Class lounge. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

|

| First Class lounge detail. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

Expect an artistry that is original, yet suffused with subtle captivation when you enter the lounge of either the Mariposa or the Monterey. The exquisite color harmonies of a tropic dawn, breaking over a surf-washed island shore… cool blues and greens brightly touched with coral pink… is your first vivid impression of this exotically beautiful rendezvous. And then the intriguing detail… the ceiling an open sky… grilles and gay canopies at the windows… light softly flooding from beneath inverted bowls of Philippine kapa shell, mounted on columns whose odd design suggests the pillars of some strange temple. Park Lane keyed to tropic tempo!

|

| First Class lounge. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

Measuring 50 ft. square. and with 15 ft. ceilings, the main lounge was the decorative show piece, done in a "rather broad adoption of Chinese Chippendale" with floor to ceiling murals of "quaint oriental figures and foliage in the style of Pillement, painted in soft coral tones on a background grading smoothly from golden yellow at the bottom to deep turquoise blue at the top." As with some of the other rooms, the windows were screened with carved wood grilles in antiqued gold leaf. The windows and doors were capped with striking canopies of carved wood, in gold and turquoise, with valences of Philippine Kapa shell, a translucent sea shell which was also used, to dramatic effect in the four columns in the room with the shell forming inverted flaring bells giving indirect lighting to the room in graded tints of yellow at the bottom to turquoise flue at the top. The plain raised ceiling was painted flat white to enhance the indirect lighting. Here, the furniture was almost entirely rattan framed with cushions in blue, green and gold while large Chinese style vases formed the bases for standing lamps with large silk shades and large potted cacti were in each corner.

|

| First Class smoking room. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

A dome for dignity, a fireplace for good fellowship and deep chairs for comfort… the smoking room… ship's center of conviviality! The walls of silver grey chestnut, laid out in checkerboard panelling, remind you of your club at home, but murals of strange and vividly colored ocean life bring you quickly back to your nomadic state of South Sea voyaging. An ideal setting for a smoke and a chat… a rubber of bridge… or an hour of listening to radio broadcasts coming in from far-away shores. Just off the smoking room is the Men's Club, a retreat that is politely but firmly immune from feminine intrusion… where masculine pursuits alone hold sway.

|

| First Class smoking room. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

The large smoking room, arranged in the classic inverted H shape around the second funnel casing and the engine hatch, featured a central area with a well in the ceiling decorated with panels of "underwater sea life in misty tones, somewhat in the Japanese style" while throughout the room was wainscotted in gray stained chestnut and a shallow beamed ceiling also in chestnut. The furniture was framed in grey oak with blue leather upholstery or cane. Rare prints of old English hunting scenes decorated the walls. Aft and on the starboardside was the men's club room, "a sanctum sanctorum for men only" which panelled in Oregon cedar and an impressive bar with an illuminated panel behind "showing Neptune and a mermaid drinking toasts to each other, while angel fish, seahorses, and a sea serpent look on."

|

| First Class dance pavilion. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

The dance pavilion undergoes a transformation every day. During the morning and afternoon it is an inviting garden with all the debonair charm of a Riviera outdoor café. Lattice of Chinese lacquer zig-zags gaily across walls of ashlar, like the bright streamers of a streamer of a carnival. Palm-shaded corners, with the tables and chairs-- the bar is nearly-- make perfect haunts for ocean-going boulevardiers. With night comes the transformation. Spotlight in revolving reflectors shed a spray of vari-colored lights on the gleaming dance floor. A bit of Bohemia… ringing with music and laughter… a scintillating night club for Broadway evenings at sea.

|

| First Class dance pavilion. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

|

| First Class dance pavilion. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

Certainly the most innovative room was the dance pavilion aft which was a large space with direct sea views on three sides and aimed to combine the functions of a veranda café during the day and a night club. The bulkheads were of a pale green material giving the appearance of stone or marble and overlaid with wooden lattice works, trimmed in green, gold and Chinese red. Live palm trees were a feature as was the large central maple dance floor with its revolving mirror sphere overhead, surrounded by small tables. French windows facing over the stern could be opened to form a quiet veranda in fine weather.

|

| First Class dining saloon. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

Bold in its departure from conventional decoration, yet splendid in its artistry, the dining salon delights the connoisseur quite as keenly as its cuisine delight the epicure. Pearly light filtered through windows of delicate shell illumines a hall nobles proportions. Murals by Paul Arndt lead the eye to the dome in which the artist has achieved a brilliant climax. Here spreads a gorgeous panorama-- clouds filmy with sunshine… gallant old ships riding to distance coral isles. In magical contrast to these ancient clippers, the Mariposa and Monterey both provide ultra modern 'air conditioning' to keep the atmosphere pleasantly tempered throughout the voyage.

|

| First Class dining saloon. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

|

| First Class dining saloon. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

The dining saloon was pacesetting, being windowless, and fully air-conditioned (only the second such example at sea, Lloyd Triestino's Victoria being the first). It was finished in dull silver with green mouldings with the central well decorated with marine paintings. Lighting was indirect in the central portion and the chairs were aluminium framed, anodized in a dull green with plain upholstery of the same hue.

Spaciousness is one of your first impressions of these two palatial liners, gained as you cross the gangplank and enter the foyer in which is located the Purser's office. Here you may have frequent occasion to 'rub elbows' with your fellow passengers, but genial choice, not from necessity. For it suggests the lobby of a metropolitan hotel in its generous proportions. In the smooth movement of electric elevators between decks, one find the character of these great ships… the ease and grace with which they accelerate a flow of suave and glowing ship life.

|

| First Class main foyer and pursers office on E Deck. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

The smoothest of ocean routes, under the fairest of skies-- here is a voyage that is supremely felicitous for outdoor life at sea. And the Mariposa and Monterey make the most of their golden opportunity. They provide more promenade deck area per passengers that many other ships. They have outdoor swimming plunges, a regulation tennis court, courses for deck golf, and broad areas for deck tennis, quoits, shuffleboard and ping-pong-- with a playground for children. For those watching their waist-line, there are a fully equipped gymnasium, electric baths and masseurs.

|

| First Class B Deck promenade. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

Inspired by the warm weather, outdoors life that characterized the South Seas/Antipodes route, the open deck, promenade and sports decks facilities were exceptional. In all, a remarkable 71 sq. ft. of promenade and recreational space was afforded each passenger (First and Cabin). In addition to the aforementioned topside sports decks, there was a broad covered promenade, with high deckheads, on either side of the A Deck public rooms and a walk-around promenade, with opening windows, on B Deck. All cabins on this deck had full windows as well.

Livability-- which is comfort, convenience and charm all combined-- sums up in on word staterooms on the Mariposa and the Monterey. Spacious enough for a foursome of bridge, they are modern home luxury gone to sea. Beds on which sea-born slumber comes like a gift from the gods… dressing tables liberally supplied with drawers… full length mirrors… private toilet… running water, hot and cold… every room with telephone and nearly all with private or connecting shower or bath. An ultra-modern ventilation system changes the air completely in a few minutes.

Space has been so liberally devoted to comfort in the de luxe suites on the Mariposa and Monterey that they suggest exclusive elegantly furnished apartments in which personal routine is delightfully unrestricted, and one may entertain at dinner or card with every appointment at hand and space to spare! Suites consist of living room, bedrooms with bath, entrance lobby and trunk room. A distinctive feature of these ships is the 'lanai' suites-- the lanai or verandad being a secluded, glass-enclosed private lounging deck, looking out upon the sea. The joy of ship life centers in the intimate, gracious charm of these luxurious 'ocean apartments.'

|

| Unique arrangement of the shared bathroom between groups of four First Class cabins on D Deck; all cabins having private toilet and washbasins with hot and cold running water. |

The First Class accommodation was, in a word, exceptional and not bettered by any liner of the era. Every cabin had a private toilet, most also having a private bath or shower, or a bath for the use of either of two adjoining rooms. The cabins on D deck situated a shared bath to every four cabins, accessed from the short passageway accessing the four rooms so that the facilities were of a semi-private nature and there was none of the traditional "down the hall in the bathrobe" liner ritual. The cabins all had full beds only for one or two persons, and no upper berths. Accommodating 475 passengers, the 250 cabins comprised 41 single-bed and 209 twin-bed cabins of which 153 had private bath or shower, 177 were outside and 73 inside. In addition, there were four deluxe suites and, most famously, eight private "lanai" or veranda staterooms. There was an extensive choice of stateroom combinations of two to four cabins to accommodate large families or parties. The beds were steel framed, in imitation of bamboo, with Simmons "Beautyrest" mattresses. All cabins had a folding card table, large full length wardrobes, dressers with vanity mirrors, hot and cold running water, telephone and 115-volt electrical outlet for curling irons. Wicker armchairs were also provided.

|

| A typical outside twin-bedded First Class stateroom. Credit: Australian National Maritime Museum. |

|

| Layout of the unique eight deluxe private lanai suites forward on A (Promenade) Deck. Note the small inside cabins for servants or children inboard. |

|

| The lanai showing the quad-folding full length French windows open directly onto the sea. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

|

| One of the four deluxe full suites. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

|

| Sitting room of one of the deluxe suites. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

The staterooms were finished in a cool grayish green, with touches of bright coloring in the rattan chairs and the shades for the bed and dresser lights. The specially designed dressers were painted green to harmonize with the walls and were decorated by "dainty painted garlands of small flowers. The furnishing of the four special suites de luxe was mostly of the Chinese Chippendale style.

If still traditionally situated aft, the Cabin Class for 222 was an entirely new rethink on "Second Class" and the finest of its kind in accommodation, deck space, public rooms and decoration. Among the amenities was an outdoor pool built in the hatch cover of the no. 3 aft hold on B Deck with ample surrounding open deck space extending almost to the stern. The principal public rooms-- lounge, smoking room with bar and veranda-- were aft on C Deck whilst the pursers office, barber and hairdressers was on D Deck and the dining saloon was on E Deck. The accommodation was aft on D and E Decks.

The decor of the Cabin Class public rooms was of entirely different character, however, than that in First, being traditionally styled with hardwood panelling or painted surfaces with conventional lighting, drapery and colors more suited to the relative scale of the rooms and, in its own way, as pleasant and tasteful.

In the cabin-class accommodations, the staterooms, foyers and corridors are decorated in a manner very similar to corresponding first-class spaces. The walls and furniture are painted similarly to walls and furniture of the first-class; and here also, coolness, comfort, and simplicity are the keynotes of the decorative schemes.

In the cabin-class, the style of decoration is more conventional, but wicker and light appearing furniture is still retained to a large extent, and the upholstery provided the bright color necessary to relieve the plain paint generally used on the walls. Gay tapestry curtains are used in the windows here. The paint on the walls in staterooms and public spaces is generally ivory and dull green. Fancy decorations are omitted in favor of refined simplicity.

|

| Cabin Class lounge. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

|

| Cabin Class lounge. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

Artistically panelled in antique oak from floor to ceiling, its central feature is a finely conceived fireplace, surmounted by a mantel of Old English design, the Cabin Class smoking room suggest the charm and beauty of the English manor. Settees and lounge chairs are attractively arranged around the fireplace, with an inviting suggestion of convivial enjoyment. The striking black and gold floor covering sets off to excellent advantage the interestingly designed chairs and tables. In the smoking room there is a novelty shop, and in near proximity, the Cabin Class veranda.

|

| Cabin Class smoking room. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

Traditionally panelled in dark oak with chairs both upholstered in fabric, leather and some with wicker backs and fitted with an electric fireplace, the smoking room struck all the masculine clubby notes.

|

| Cabin Class dining room. Credit: Pacific Marine Review. |

The Cabin Class dining salon is another triumph in investing a room with distinctive beauty and charm. From the soft lacquered panels, the spritely figured overhangings on the windows and the gay buff and slate motifs on the floor covering, comes an impression of ease, well being and contentment, made a substantial reality by the excellent of the Oceanic cuisine. With exquisite public rooms, with talking pictures, daily newspaper, radio, dancing, outdoor swimming plunge and ample deck area for sports, Cabin Class passengers enjoy every facility for comfort and diversion.

|

| Cabin Class dining room. Credit Huntington Museum. |

The dining saloon was finished in dull green with brightly colored curtains at the portholes and checkerboard rubber decking in complimentary shades. The chairs were identical to those in the First Class saloon.

|

| Cabin Class stateroom. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

In its close approximation to First Class facilities Cabin Class on the Mariposa and the Monterey sets a new standard in trans-Pacific travel. This is abundantly manifest in the staterooms. There is the came conception of spaciousness, the same regard for convenience and the provision for ventilation. All Cabin Class staterooms are equipped with individual beds, dressing table, capacious wardrobes, thermos bottles, running water, hot and cold, individual telephone… facilities that assure the utmost comfort combined with the advantage of travel economy.

|

| Cabin Class three-berth stateroom. Huntington Museum. |

If the First Class accommodation was the acme of ship living, Cabin Class was a revelation, indeed it was in many cases superior to First Class in Aorangi. In the essentials-- telephone, elaborate bureaus, wardrobes, hot and cold running water, lighting and furnishings-- the cabins were indeed comparable to those for First Class. The principal difference being the provision of upper berths and even these were of a novel design, being folding with a double hinged arrangement that could be stored in a ceiling-mounted box, allowing almost full headroom over the beds and not giving the appearance of folding upper berths. Of the 70 Cabin Class cabins, there were five two-berth, 36 three-berth and 29 four-berth with 15 with the "Bibby" arrangement with porthole, 35 outside and 20 inside.

The 359 officers and crew: deck department 46, engine department 46, steward's department 240, purser's department 12, medical department 3 and watchman 12.

In accommodation, public rooms and deck space, decor and appointments, speed and style, Mariposa and Monterey were indeed the Sovereigns of the Pacific. Now, they embarked on a nine-year reign Beneath the Southern Cross during which they nailed the Stars & Stripes and the Oceanic houseflag to the highest masthead on the ocean highway to the South Seas.

And now for a moment of easy chair reflection glowing in your mind of those two giant super-liners, the Mariposa and the Monterey coursing though gold-tinted vistas of the South Seas.

They are enacting one of the miracles of modern ocean transportation-- drawing continents closer together by days-- opening new avenues gleaming with fresh interest. Swift transport to the singing isles of Hawaii… to the coral-fringed loveliness of tropical Samoa… to the weird haunts of the barbaric in exotic Fiji. Then on to new sights and new charms of the wonderlands of New Zealand and Australia.

Matson-Oceanic brochure, 1937

Halcyon Heyday: it would be difficult to conceive of another long distance ocean trade route more transformed-- more utterly or as suddenly-- than that from the United States to the Antipodes in the first half of 1932. American ambitions to show or place in the field of ocean competition were, there and then, rewarded with a dominance scarcely dreamt of, let alone so triumphantly realized. Even more so, achieved amid the very worst of a now global economic and trade depression. Cut short by the war, it was nevertheless a nine-year dominance like none other by an American line and ships and one that perfectly and pleasingly coincided with a true heyday of ocean travel. For a pair of ships that endured for decades, those first nine years were doubtless their best.

1932

Beginning a career that came to be associated with passing through the Golden Gate, departures to the strains of the Royal Hawaiian Band in the shadow of the Aloha Tower and under Sydney's new and epic Harbour Bridge, U.S.M.S. Mariposa instead cast off from a chilly and cloudy Manhattan on suitably impressive delivery voyage/cruise that would not only introduce her to regular route ports but circle the North Pacific before winding up at her homeport of San Francisco whereupon she took up her Oceanic mail route duties.

|

| Mariposa sails from Pier 86 North River on her maiden voyage to Los Angeles and San Francisco, 16 January 1932. Note the awning over her forward swimming pool. Credit: Mariners Museum |

Mariposa's delivery voyage was sold both as a trans-Canal New York-Los Angeles-San Francisco voyage carrying First and Cabin Class passengers or as part of her "Coronation Cruise" around the Pacific and Orient from San Francisco which was First Class only. Sailing from New York on 16 January, 1932, Mariposa called at Havana on the 19th (sailing at midnight), arrived Cristobal 22nd, transited the Panama Canal, leaving Balboa at midnight on the 22nd, stopped at Los Angeles on the 29th (8:00 a.m.- 4:00 p.m.) and docked at San Francisco at 11:00 a.m. the following day.

|

| Mariposa sailing down the North River, California-bound. Credit: Mystic Seaport Museum, Rosenfeld Collection. |

|

| Mariposa passing the lower Manhattan skyline. Credit: Pacific Marine News. |

In a true Jones-White triumphal moment, Mariposa cleared New York on 16 January 1932 with 300 passengers (including Matson President W.P. Roth) just as Dollar Line's new President Coolidge returned to the port to conclude her own maiden voyage. Mariposa made quick work of her trip to the West Coast and on the 28th was reported to have been averaging just under 20 knots north of the canal and did the 2,913 miles from Balboa to Los Angeles in 6 days 9 hours.

|

| Mariposa's triumphant arrival at Los Angeles (Wilmington), her port of registry. Credit: Mariners Museum |

Her arrival at Wilmington, Port of Los Angeles, her port of registry, at 6:00 a.m. on 29 January 1932 occasioned considerable interest and press coverage, the Long Beach Sun reporting that "shipping men here agreed that the Mariposa was the finest looking ship they had ever seen enter this port." Mariposa docked at the LASSCo Pier 157 Wilmington at 8:30 a.m., but her visit was fleeting and she was off at 4:00 p.m. bound for the Golden Gate.

|

| Credit: Illustrated Daily News, 30 January 1932. |

Registry notwithstanding, the newest Matson-Oceanic liner was always San Francisco's own, her true homeport and given a memorable reception there on arrival on the 30th:

Undaunted by leaden skies and the drip of rain, San Francisco extended a joyeous welcome yesterday to an $8,000,000 addition to her merchant marine. The new Matson liner Mariposa steamed into port at 11 a.m. on her maiden voyage from the East coast, ready to start regular runs to the Orient and the South Seas. Met at the Golden State by airplanes overhead and a fleet of small craft in the bay, the speedy vessel, to the accompaniment of whistles and sirens, outdistanced her convoy to her berth where State and city officials joined in welcoming officers and crew. There Captain Joseph H. Trask, commodore of the Matson fleet and skipper of its new flagship, received the welcoming committee, preceded by the Municipal Band.

San Francisco Examiner, 31 January 1932

|

| Credit: San Francisco Examiner, 30 January 1932. |

The Mariposa was given a rousing reception upon its arrival in the bay from the south, Saturday morning. While yet far out to sea airplanes began flying over the craft and dropping great bunches of purple heather onto the decks. At the Golden Gate gaily decorated launches and power boats formed into parade lines and escorted the new white hulled beauty of the seas to the Matson dock. The parade down the bay was a genuine progress of acclamation for at every pier freighters and passenger liners opened their sirens and whistles to full blast in a throaty welcome. At the Matson docks thousands of people crowded in to aid to the reception.

Oakland Tribune, 1 February 1932

|

| The brochure cover art for Mariposa's South Seas & Oriental Cruise. Credit: Huntington Museum, |

|

| The route of the cruise had Mariposa first visit what would be her regular service ports in the South Pacific and Antipodes. Credit: Huntington Museum. |

On 2 February 1932 Mariposa sailed from San Francisco (and from Los Angeles on the 3rd) on her South Seas & Oriental Cruise. "She was cheered on her way by a crowd that packed the Lassco piers, while the sirens and whistles of ships in port shrieked a bon voyage that was even more colorful than the welcome she received upon arrival from New York last week." (Los Angeles Times, 4 February 1932). In addition to her master, Capt. Trask, there were three other Matson captains aboard: Capt. William A. Meyer, former master of Ventura, as Staff Captain, and Capt. C.A. Berndtson, former captain of Malolo, as guest pilot. Capt. James Rasmussen, Honolulu port captain for Matson, also aboard. Chief Engineer C.J. Knudsen was formerly on Ventura, J.M. Ford, Jr., formerly of Malolo, was Chief Purser.

Among the passengers aboard were Matson President W.P. Roth (as far as Honolulu), Matson Chairman of the Board Edward D. Tenney and daughter, Mrs Roth and daughters Lurline and Bernice, Matson Vice President Wallace Alexander and Mrs. Alexander., cartoonist Robert L. Ripley, powerboat racing champion Marion Barbara "Joe" Carstairs and composer Robert Friml.

|

| Mariposa ready to sail from Los Angeles on her "Coronation Cruise" to the South Pacific and Orient. Credit: Los Angeles Times, 4 February 1932. |

This reversed the order of ports recently visited by Malolo on her third such cruise to introduce the new ship to her regular calls in the Antipodes first as well as give better weather for the Northern Pacific ports later in the voyage, coinciding with cherry blossom season in Japan. Limited to 550 in First Class and "in the Grand Manner of Matson," the superb itinerary called at Honolulu, Pago Pago, Suva, Auckland, Sydney, Port Moresby, Thursday Island, Macassar, Batavia, Singapore, Bangkok, Manila, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Chingwangtao, Miyajima, Kobe, Yokohama, Honolulu and Hilo before returning to San Francisco on 28 April 1932 after steaming 29,491 miles.

|

| Credit: Honolulu Advertiser, 8 February 1932. |

|

| The Honolulu newspapers went "all out" to welcome Mariposa and her passengers on her maiden call. Credit: Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 8 February 1932. |

Honolulu, of course, afforded the new ship a memorable reception when she arrived on 8 February 1932: "The vessel was met off port at daylight by a committee from the chamber of commerce together with a group of lei girls who decorated the passengers with flower leis. The Royal Hawaiian Band also went off port and serenaded the big ship as she came into port. As the Mariposa neared Pier 2, hundreds of automobiles lining the pier front honked their welcome while craft in the harbor large and small tied down their whistles. Above all the din could be heard the shrill blast of the siren on the Aloha Tower." (Honolulu Advertiser, 9 February 1932). She had 506 passengers aboard, 200 landing at Honolulu and another 50 embarking. A luncheon reception was held aboard for local steamship men and business leaders.

|

| It was atypically cloudy in Honolulu for the maiden arrival there. Credit: Mariners Museum |

Mariposa sailed at midnight 9 February for Pago Pago and Suva. "Mariposa arrives at Suva, Fiji "aroused enthusiasm of natives here today when the giant Matson ship pulled into dock here. A military and native band, accompanied by Fijian girl singers serenaded the passengers as they came ashore. Native dances and other receptions were included in the welcome of the British governor." (Fresno Bee, 18 February 1932).

|

| Mariposa at Pago Pago. Credit: U.S. Library of Congress. |

|

| And raining in Auckland.. Credit: Auckland Star, 23 February 1932 |

Like a ship out of a story-book she came—the Mariposa, newest unit of the Matson fleet. Even through an unkindly rainstorm she appeared as a thing of dazzling whiteness, her huge hull and towering upper-works glistening with fresh paint. From each of her two lowset funnels trailed the finest wisp of smoke, and from her raking masts fluttered long strings of bunting. Above her cruiser stern flew the Stars and Stripes. Her smoothly-running engines made it seem as if the ship was softly talking to herself as she steamed up harbour, her sharp bow, with just the suggestion of a "are about them, giving birth to thousand upon thousand of long ripples that stretched away on either side to lap the distant shores. And then, when abreast of the long Stanley Bay wharf, the Mariposa, hailed by her owners as the Queen of the Pacific, lowered a brand-new anchor to the bed of the Waitemata.

It was in no way an ideal morning for the white giantess first to display her splendour in Auckland. She rode to her anchor on a sullen tide, and glowering rain clouds emptied their contents from above. But even in this dismal setting the Mariposa, dressed from boat deck to waterlina in shimmering white, looked a typical cruise ship, a ship of the tropics. Hurrying ferries that heeled perceptibly as their passengers crowded to one side appeared almost out of place. One pictured the Mariposa basking in a sun-drenched harbour, with Island canoes clustered about her and native huts nestling among vivid green palms on shore. It was the ship's great whiteness that made one's imagination whisk her back to the Islands whence she had come.

Auckland Star, 20 February 1932

Even if greeted by heavy rain, Mariposa's arrival at Auckland the morning of 20 February 1932 created a sensation and crowds were on hand to see her dock at the Central Wharf, aided by the tug Te Awhina, the sightseers remaining throughout her two-day stay. Those fortunate enough to get passes to inspect the vessel were captivated and all agreed nothing quite like her had been seen in the port.

|

| Mariposa berthed at Auckland. Credit: Auckland War Memorial Museum. |

Auckland could scarcely have failed to be captivated by the efficiency and elegance of the Mariposa, first of three new Matson liners engaged in the trans-Pacific service, which arrived at Auckland shortly after 6 a.m. on Saturday… This admiration was won deservedly by the Mariposa, which contributes so much that is new to the Dominion's store of shipping knowledge… at night the Mariposa gave Auckland's waterfront a newer appeal. The liner's bulk was a dusky whiteness of indeterminate limits, broken by chains of lights. The floodlighting of the two funnels completed the picture. There was, in Auckland's mind, a conviction that the Mariposa, the Monterey and the Lurline will form a stately and famous trio"

New Zealand Herald, 22 February 1932

|

| Credit: Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections AWNS-19320224-34-1 Auckland Weekly News 24 February 1932 |