When blinding storm gusts fret thy shore,

And wild waves lash thy strand,

Thro' spindrift swirl, and tempest roar,

We love thee windswept land.

from Ode to Newfoundland, Sir Cavendish Boyle, 1902

In 1913 a small ship left Liverpool on her maiden voyage to St. John's N.F. and Halifax. She excited little comment, she was neither big nor fast and she carried comparatively few passengers, yet she was quite important in many ways and was destined to have a career far longer, more varied and more active than most North Atlantic passenger and cargo ships, and she improved steadily as she grew as she grew older. This was the Digby, built by Irvine's Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company at West Hartlepool for the Furness Warren Line's service from Liverpool to St. John's, Halifax and Boston.

J.H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, July 1967.

Of all Britain's North Atlantic liners of the early 20th century, few are as obscure yet longlived as Furness Withy's little Digby of 1913. Initially plying the equally overlooked route from Liverpool to Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, the diminutive 3,800-grt vessel performed sterling and stalwart service during a fulsome career spanning 52 years.

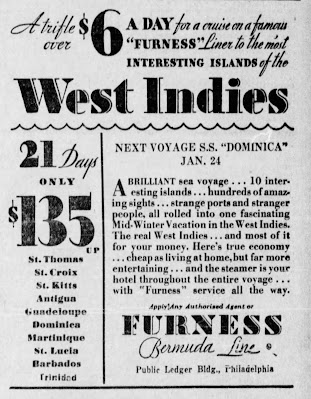

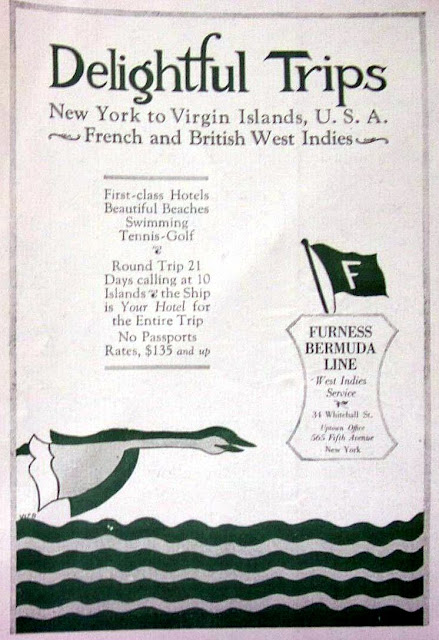

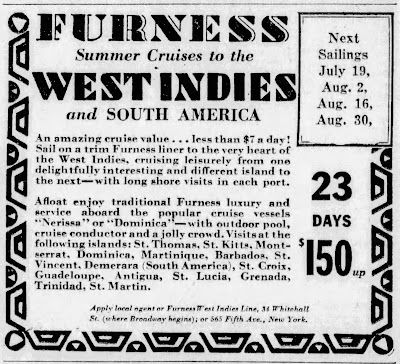

Here, our principal focus will be on her initial 22 years with Furness Withy linking Newfoundland, Britain's oldest colony, with Mother Country across the most challenging of all trans-Atlantic routes with its ice floes, bergs and fog, serving as an Armed Merchant Cruiser in the Great War and, in the mid 'twenties, in a complete change of climate and route, sailing to the West Indies as Dominica. Her ensuing career as United Baltic's Baltrover saw her carrying pre-war refugees from the Nazis to England and renewing her links with Newfoundland and Nova Scotia during the Second World War and finally, plying the Mediterranean as Ionia of Hellenic Mediterranean Lines. With a 52-year career matched in longevity among Edwardian Era liners only by Virginian's 50 years, time to finally discover the forgotten...

s.s. DIGBY, 1913-1925

s.s. DOMINICA, 1925-1935

s.s. BALTROVER, 1935-1946

s.s. IONIA, 1947-1965

|

| Early postcard of s.s. Digby. Credit: https://www.simplonpc.co.uk/ |

|

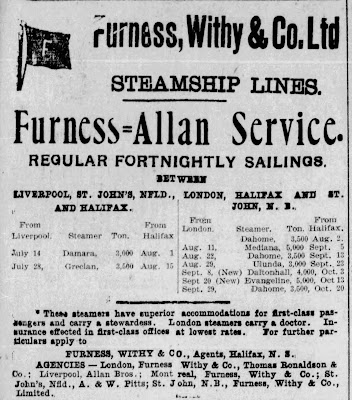

| 1924 leaflet on Furness Withy's Newfoundland service. Credit: Memorial University of Newfoundland Digital Collection. |

...but I am perfectly certain this vessel [Digby] will create an impression in the Newfoundland service. We propose to run her to Newfoundland during the whole of the summer, and we estimate that assuming she leaves Liverpool on a Sunday she can quite easily land her passengers in Newfoundland on Thursday night or morning; that is, of course-, provided that there is no fog or ice; and I think the Newfoundland people will find that they then have a facility which will obviate the necessity of their either going to Halifax. Montreal or New York."

Lord Furness to Sir Edward Morris, Premier of Newfoundland, April 1913.

When R.M.S. Nova Scotia (II) and Newfoundland (II) were sold at the end of 1962, it marked the passing of a 64-year-old direct Furness Withy passenger, mail and cargo link with their namesakes, linking Britain and the Canadian Maritime Provinces and its oldest overseas possession, Newfoundland.

The aptly named Newfound Land, the world's tenth largest island (encompassing 47,720 sq. miles), is the oldest European settled land in the Americas. Most recent research dates the first Viking settlement there to 1021, 470 years before the arrival of Columbus, or almost exactly 1,000 years ago. Its modern history dates to 1497 when Italian navigator Giovanni Caboto (aka John Cabot), on commission by King Henry VII, landed there on 1497 and on 5 August 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert established Newfoundland as Britain's very first overseas colony and beginning the British Empire under Queen Elizabeth I.

Fought over by the English and French as was much of North America in the mid 1600s, Newfoundland emerged definitively and resolutely British at the dawn of the 18th century and during the American Revolution, it and Nova Scotia were Loyalist bastions although the latter and Ontario benefited from an influx of Loyalist refugees more than remote Newfoundland. Situated in one of the richest fishing grounds of the Atlantic, Newfoundland's economy was dominated by maritime enterprise but rich, too, in timber and minerals. In 1825 Newfoundland become a Crown Colony, gaining its own constitution seven years later and in 1907 it became a Dominion of the British Empire.

|

| c. 1840s map of Nova Scotia (bottom left) and Newfoundland (upper right) with St. John's at the south eastern tip of the islands. |

Its small population (124,000 in 1864) and political separation from the newly confederated Canada (1867) and being slightly off the sea lanes into the St. Lawrence, meant that Newfoundland's place in the rapidly developing network of trans-Atlantic steamship routes was dependent on mail contracts placed by its government and the Home Government in combination with Halifax as inducement for through traffic as well as reflecting Nova Scotia as a principal supplier of produce, meat and vegetables to the island. In terms of distances, the Capital of Newfoundland, St. John's on the far eastern side of the island on its own peninsula and having a superb natural harbour that was usually ice free even in the harshest winters, was just 1,933 sea miles from Liverpool, 550 miles from Halifax and 910 miles from Boston, but 1,600 miles distant from Montreal, ensuring its overseas links were entwined with Nova Scotia and New England.

Allan Line, the principal company on the Great Britain-Canada route, had since 1870, arranged to have their Glasgow-Quebec-Montreal steamers put into St. John's once or twice during August and September. In April 1873 the company was awarded a mail contract under which the steamers of the Liverpool-Halifax-Norfolk-Baltimore service called fortnightly at St. John's except during January, February and March, when ice often closed navigation between St. John's and Halifax.

In 1884, Bowring Brothers Ltd., which had dominated and indeed originated much of Newfoundland's commerce and industry from 1811 onwards, formed the New York, Newfoundland and Halifax Steamship Company which owing to the red St. Andrews cross on a white band on their funnels, was better known as the Red Cross Line. This was the principal line connecting St. John's with the U.S. eastern seaboard and, as we shall see, eventually figured in the long career of Digby.

Furness Line (founded in 1878 by Christopher Furness (1852-1912)) had connections with the Atlantic coast of Canada almost from the beginning with cargo and passenger services to Halifax and St. John (NB) commencing from London on 10 September 1884 with Newcastle City (1884/2,129grt) followed by York City (1881/2,325grt) on the 30th.

|

| Advertisement for the Furness Line's initial services from London to Boston and to Halifax and St. John (NB). Credit: Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 8 September 1884. |

In August 1890 the Furness Ulunda (1886/1,789 grt) was stranded off the Canadian coast, at Briar Island, Bay of Fundy, six hours out of St. John, NB. Refloated, she was "sold for a trifle" and retaining her name, became the first ship of the rather ponderously titled "Halifax (NS), St. John's (NFL), London and Liverpool Line of Steamers," upon departure from Halifax on 24 November 1891. With her sailing from Liverpool on 20 March 1892 for St. John's and Halifax, Newfoundland, finally had her own dedicated trans-Atlantic passenger, cargo and mail service. Ulunda reached St. John's on the 28th with 2,700 tons of cargo to land there, the second largest consignment to date for the port. A year later the line added Barcelona (1878/1,802 grt) and Moruca (1883/1,594 grt) to increase the service to a fortnightly frequency which in December 1893 was restyled as the Canada and Newfoundland Line of Steamers.

Following Furness' quickly established pattern of acquiring lines and specific routes, The Canada and Newfoundland Line of Steamers was purchased on 30 April 1898 and Furness' 2,470-grt Dahome added to the service. Furness now maintained separate routes to St. John's (NF) via Halifax and to St. John (NB) via Halifax in addition to one direct to Boston.

In the formative years of the Dominions of Canada and Newfoundland (recalling the latter was not part of Canada until 1947) mail contracts were offered to maintain essential mail and passenger services as well as develop exports which in the case of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, centered on apples requiring specialised ventilated carriage, and for Newfoundland, codfish, fish, and seal oil and skins. Paramount in the Canadian trade, Allan Line, expanded their core St. Lawrence market to encompass the Atlantic provinces and Newfoundland, and they and Furness variously competed and cooperated for the slowly developing trade which did not benefit from burgeoning immigration enjoyed on the direct St. Lawrence routes.

On 23 June 1900 Furness Withy and Allan Line announced a new joint service on the Liverpool-St. John's (NF) and Halifax run with Allan contributing Grecian and Furness Withy Damara and Ulunda. Damara commenced the service from Liverpool on 14 July and from Halifax on 1 August followed by Grecian on 28 July.

More ambitious plans were formulated for the Halifax and St. John (NB) run. On 28 June 1900 the Furness Withy office in Halifax received plans for the first of two new 5,000-ton steamers to be built by A. Stephens & Sons, Linthouse, for the service, measuring 372 ft. x 45 ft. of which "the principal features are the elaborate arrangements for passengers and fruit." As elsewhere on empire routes, passengers and fruit were proving a congenial and profitable combination both favouring a fair turn of speed and direct route and frequent sailings as well as the latest technologies being formulated for mechanical ventilation and cooling chambers, in this case provision to carry 30,000 barrels or 90,000 bushels of apples. Both were especially built for navigating in ice with more and heavier scantlings and thicker shell plates forward. Designed for a 13-knot service speed, each had a single-screw powered by triple-expansion (28", 46" and 75" dia. cylinders with a 51" stroke) and four single-ended boilers.

The accommodation was of a very high character indeed, setting a new mark for the route and for Furness passenger ships going forward. The Halifax Herald noted that the ships "will have the most luxurious passenger accommodation for 70 first class passengers arranged amidships under the bridge and also the large deck-houses on top of the bridge with a very handsome and commodious dining saloon the full width of the vessel at the fore end of the same. On top of the bridge deck the are spacious deck houses for large music saloon and smoke rooms, etc., which will be most artistically decorated and finished elegantly. Abaft the music saloon in the deckhouse there are a number of large special staterooms. The captain and officers are berthed in a separate deckhouse on top of the saloon house, in close proxmity to the navigation bridge. The bridge deck, being extra long, affords a very fine promenade for the passengers, and is considerably more spacious than usual in passenger steamers." A seperate Second Class for 24 was in the poop and a further 48 Third Class could be carried in the 'tween decks.

|

| The lovely Evangeline on trials. |

The first sister was launched 25 September 1900 as Evangeline by Mrs. F.J. Stephen followed by Loyalist christened by Mrs. J. Stephen on 26 December. No time was lost in fitting out and Evangeline underwent trials on 26 October, averaging 14.5 knots, thence directly on her maiden voyage, arriving at St. John on 5 November. Loyalist left Glasgow on 31 January 1901 for trials and off on her first crossing, reaching St. John on 11 February.

Enjoying the briefest of heydays, Evangeline and Loyalist reigned as the prettiest pair of sister ships sailing to Canada as well as among the fastest. On 31 August 1901 Loyalist surprised all by reaching Halifax from London a day ahead of schedule, making the run in a record eight and a half days. Eastbound, Evangeline docked at London 8 September after a record trip of 9 days 2 hours.

The first years of the 20th century were not sanguine ones for British shipping with the trade disruption caused by considerable number of ships taken up for trooping and supply to South Africa during the Boer War and the creation of the International Mercantile Marine by J.P. Morgan with its attendent rate fixing and traffic consolidation. Rebuffed in his own efforts to create a British shipping combine to compete, Sir Christopher Furness rather dramatically re-oriented Furness Withy away from set passenger trades as result.

Already proving in excess of traffic requirements, Evangeline and Loyalist were sold in February 1902 to Lamport & Holt for their new New York-River Plate service. Loyalist left Halifax for the final time on 27 December 1901 followed by Evangeline on 3 January 1902. Rather confusingly, they were replaced, of sorts, by the much smaller former Clan Mackinnon (1891/2,266 grt) renamed Evangeline (II) and Clan Macalister (1891/2,294 grt) renamed Loyalist which carried a small number of passengers to maintain the service.

Prompted by an upturn in freight rates, Furness Withy began an expansive shipbuilding programme for their component lines in 1910. From 1911 to the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914, some 75 ship totalling 350,000 gross tons were delivered, of which 50 came from the group's own Irvine's Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co., Hartlepool. This expansion also reflected the increasing influence of Director Frederick Lewis who would transform the group's fleet, operations and character over the ensuing two decades, especially regarding an agressive return to the passenger trade on routes to the Canada, West Indies, Bermuda and the Americas. Furness Withy and their component companies were "back" on the liner trades.

In a busy year, Furness acquired in 1912, through its subsidiary, The British Maritime Trust, White Diamond Steamship Co. which dated from 1839 as the White Diamond Line of Sailing Packets on the Liverpool-Boston route which was bought by George Warren by the mid 1850s. Under Furness ownership, the company was restyled as George Warren & Co. Ltd. and the following year Sagamore (1892/5,204grt) and Sachem (1893/5,036grt) were refitted with 58 Second Class berths and with Michigan with berths for 12 passengers began a fortnightly passenger service to Boston.

At the same time, Furness embarked on a new commitment to their own Canadian routes to St. John, NB, St. John's, NF, and Halifax as the North American Dominions of Canada and Newfoundland enjoyed prosperous times, expanded trade and benefited from substantial immigration from the British Isles.

It will be patent to you that are laying ourselves out to cultivate permanent business in the various directions in which the trade of the world promises to be of an enlarging character and which are to be relied upon for their constancy. This especially the ease in regard to our Canadian extensions. We at home are only beginning to realise the enormous field for enterprise which the development of Canada is offering. The Dominion is calling for capital and energy, for brain and sinew; and the opening up of the great lines of rail from sea to sea, combined with the development of traffic on the Great Lakes, renders possible the harvesting of the rich natural resources in which that country abounds, although much caution and experience, on the spot are called because of the number of undesirable schemes put forward.

Lord Furness, 27 July 1912

A departure from the company's usual practice was made by the construction of the steamer Digby for the passenger service to Newfoundland, which the Furness Withy Line decided to build up and which has progressed out of all recognition.

Weekly Commercial News, 12 June 1926

It is much to be regretted that the direct Allan Line from Liverpool to St. John's, which only takes seven days, should not have larger and more up-todate steamers. The largest boat is under 5,000 tons; not very comfortable for crossing the Atlantic. As the Allan Line run excellent boats to Quebec, there must be some good reason for the local service to St. John's not being better served.

Sport in Vancouver and Newfoundland, 1912

At the time, Furness' service from Liverpool to St. John's and Halifax was maintained by Almeriana (1899/2,826 grt), Durango (1895/3,008 grt) and Tabasco (1895/2,897 grt). A rival Newfoundland fortnightly service, under mail contract, was operated by Allan Line's Mongolian (1891/4,838 grt), Carthaginian (1884/4,444 grt), Pomeranian (1882/4,207 grt) and Sardinian (1874/4,340 grt). All were old and slow (11.5-10 knots) and only the Allan Line steamers had passenger accommodation of approximately 50 First and 50 Second Class each. The sailings between the two lines were coordinated so as to provide a weekly service.

Not wishing to be overly ambitious after Loyalist and Evangeline, Furness envisaged new combination cargo-passenger tonnage of comparable size and capacity to the existing Allan Line steamers, but faster (12.5 knots) and from the onset it was planned to eventually build three new ships to maintain the fortnightly St. John's and Halifax run.

Plans for the first passenger-cargo ship to be built by Furness Withy since Loyalist and Evangeline were begun in winter 1911 and judging from the 22 April 1912 date on drawings of her rudder submitted to Lloyd's Register, the ship had already been assigned yard no. 527 by Messrs. Irvine's Shipbuilding and Dry Docks Co., Ltd. and her engines to be built by Messrs. Richardsons, Westgarth & Co., Hartlepool. The exact date of her contract and laying down are not known and what would prove one of Furness Withy's most profitable and successful vessels as well as one which set in motion the firm's re-entry into the passenger trade, was originated, constructed and launched in relative anonymity.

During the 21st annual meeting of Furness, Withy & Co. Ltd. in West Hartlepool on 27 July 1912 1912, it was announced that "Further to develop our old-established lines between Halifax and London and Liverpool, a new steamer of special design for passengers and cargo is in the course of constructions at the Harbor shipyard, G.B. and will be placed on the sailing berth within the next few months. It is intended to augment this service by building two more cargo and passenger steamers for the increasing Canadian trade." It's interesting that the emphasis was on the Nova Scotia terminus rather than the Newfoundland call and this was perhaps influential, too, in the choice of name for the first of the new ships for the route. By early autumn 1912, the new ship was known as Digby, named after the small fishing port on Nova Scotia's Bay of Fundy and famous for its scallops. The Evening Mail (Halifax) of 11 September 1912 reported:

Furness Withy company intend to add three new freight steamers for their London-Halifax fleet. One of these, the Digby, will here in December, the other two will be ready for this route sometime next September.

The Digby, now in the yards of the Irvine Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, Limited, of England, will be a ship of 5,100 tons capacity, 350 feet long, 50 feet beam, 25 feet 6 inches molded, and 23 feet 6 inches draft of water. She will have six watertight bulkheads. Her speed will be thirteen knots. Provision is made for the accommodation of seventy passengers.

The Gazette (Montreal) followed with the report on 26 September 1912 "... the Digby, will cross the Atlantic for the first time early in January at the latest."

|

| Ships on the ways of the Hartlepool yards of Irvine Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company c. 1912, the almost complete hull on the centre slipway is unidentified but could well be Digby. |

On 10 November 1912 Lord Furness passed away after a several months illness, aged only 60, and succeeded by his son, Stephen, who would, in turn, die in an accident on 6 September 1914, and replaced by Marmaduke Furness (b. 1883) whose lack of shipping experience resulted in Frederick Lewis, a Director since 1899, assuming an increasing role in the group's shipping enterprises and particularly in a revival of the trans-Atlantic passenger trade. Indeed, Digby's inception doubtless owed much to Lewis who would, in the span of two decades establish the Furness Withy Group as leaders in passenger services in and to the Americas and Canada.

Owing to the lamented death of Lord Furness, late chairman of both companies, the vessel was put into the water as quietly as possible, without any christening ceremony.

The North Star, 28 November 1912

Out of respect for the mourning period for Lord Furness, plans for an elaborate christening ceremony for Digby were shelved and when she was launched on 27 November 1912 it was completely without any occasion whatsoever, nor do any photographs of the occasion appear to have been taken or extent. It was a desultory beginning to a career that would extend into five decades.

Digby's commander was appointed in December 1912, Capt. J.H. Trinick, Commodore of Furness Canada fleets, who had served on the Canadian routes for 25 years, first visiting Halifax on 28 March 1888 when he brought in the new Boston City and also the maiden voyage of Shenandoah which he commanded until his appointment to Digby. Shenandoah left London on the 6th commanded by Capt. Blaxland, and Capt. Trinick will take some leave before supervising the completion of Digby.

The Furness Line propose to run the s.s. Digby in the Newfoundland trade for which it has been specially designed. It is now fitting out and is scheduled to leave Liverpool on May 8th.

In a letter to the Premier, Sir Edward Morris, Lord Furness says: "The s.s. Digby has accommodation for 60 first-class passengers and for 30 second class passengers, in addition to which she has has a considerable quantity of refrigerator space. She is fitted up in a most luxurious style, having a magnificent saloon, social hall, lounges, etc.. and there is no better accommodation on any vessel crossing the Atlantic. There are, of course, steamers with more accommodation; but I am perfectly certain this vessel will create an impression in the Newfoundland service. We propose to run her to Newfoundland during the whole of the summer, and we estimate that assuming she leaves Liverpool on a Sunday she can quite easily land her passengers in Newfoundland on Thursday night or morning; that is, of course, provided that there is no fog or ice; and I think the Newfoundland people will find that they then have a facility which will obviate the necessity of their either going to Halifax. Montreal or New York.'

Lord Furness has in view the building of another vessel of this class, so as to give a regular service and to form the fast mail service which is under the consideration of the Government.

Evening Telegram, 18 April 1913

As reported on 22 April 1913, with the advent of Digby, Almeriana would be shifted from the Liverpool to St. John's and Halifax run to the Liverpool to St. Lawrence service.

|

| Digby on trials. Credit: awatean, shipsnostalgia.com |

Throughout the trial the engines and all auxiliaries worked admirably.

The North Star, 3 May 1912

Digby left Hartlepool on her acceptance trials on 30 April 1913 with four runs north and south on the Whitley Bay measured mile recording a maximum speed of 15.25 knots and an average speed of 14.38 knots, all considerably in excess of her 12.5-knot service speed.

Aboard for the trials followed by luncheon were Mr. A.S. Purdon (of Messrs. Irvine’s), Mr. Einar Furness (director of Furness, Withy, Co.), Mr. Tom Furness, Master Christopher Furness. Mr. D. Cooke (directorr), Mr. R. Sargeant, Mr. W. T. Robson (secretary of Neptune Steam Navigation Co., Ltd.), Mr. C. H. Clayden, W. J. Bracbenbmy, Mr. D. Ross, Mr. Faith (London), Mr. Bainbridge (London), Mr. Kennett (of Messrs. Richardsons, Mr. H. Barnes (secretary of Messrs. Richardsons). Mr. Boyd and Mr. McAnalau (of Lloyd’s), Mr. Marshall (Board of Trade), Mr. Hood, Mr. Roberts (of Messrs. Irvine’s). Mr. A. H. Walker. Dr. Cooke, and Mr. W. Wallace.

Her trials considered "most satisfactory," Digby proceeded to Liverpool on 1 May 1913 from West Hartlepool where she berthed at Canada Dock two days later to load for her maiden voyage to Newfoundland and Nova Scotia.

Britain's Ancient Colony in North America would finally have her very own passenger liner, establishing a Furness Withy tradition of service to Newfoundland that would endure until 1962 through three generations of ships designed and built to serve "Thro' spindrift swirl, and tempest roar," that windswept land.

A staunch and comfortable little vessel...

British Passenger Liners of the Five Oceans.

She was not a very large ship, having a gross tonnage of just under 4,000, but she was completely fitted as an intermediate passenger steamer of the most comfortable type and her triple expansion engines gave her a speed of comfortably over 15 knots on trial. She was specially designed for the carriage of fruit and Canadian dairy produce as well as for comfortable passenger accommodation.

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 28 July 1925

The little, utterly conventional Digby was nevertheless the first passenger ship especially designed and built for the Newfoundland trade, and as events proved, outlived all her Canadian contemporaries by many years. Indeed, she was one of the most enduring of all Edwardian liners, exceeding even the staunch Virginian (1905-1955) by three years.

|

| Digby cranking out 15.15 knots on her trials. Credit: awatean, shipsnostalgia.com |

The Digby at first sight appeared to be a normal cargo steamer of quite usual design, but on looking closer, her full length boat deck and open poop gave away her passenger carrying role.

J.H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, July 1967.

Possessing the perfect proportions that defined the Edwardian liner, Digby was a thoroughly handsome and well found ship and one that, if anything, looked better as she aged. As built, she was as simple and straight forward as any of her era, with a sturdy and businesslike demeanour that suited the rigours of her route and workaday quality of her cargo and passenger trade. She was delivered in the old Furness colours of black funnel and hull with a white sheer line which by 1914, had been supplanted by a medium blue band with a white block letter "F" on the funnel, emulating the houseflag.

In measurement (3,966 gross tons, 2,233 net tons, 4,886 deadweight tons, 350 ft. 8 ins. (length bp), 365 ft. (length overall) and 50 ft. (beam), Digby was not too different from the many cargo vessels Irvine's churned out for the many Furness group lines as well as independents. By comparison, she was about 20 ft. shorter than the earlier Evangeline and Loyalist but beamier. Indeed, she ranked as one of the smallest of all purpose-built Atlantic liners of her era and about the size of Northland Prince/St. Helena (1963).

Digby had three overall decks: Shelter, Upper and Main and a full length (128 ft. long) Bridge Deck and a 43-foot-long raised forcastle. The hull was divided into eight watertight compartments by seven bulkheads, had a full double bottom and the forward part of the hull was heavily strengthed in plates and scantlings for navigating in the ice fields she would so often have to contend with on her route.

|

| The magnificent builder's model of Digby at the Hartlepool Maritime Museum. Credit: shipsnostalgia.com, dlongly |

The vessel has been specially designed and built for the carriage of Canadian fruit and dairy produce, large quantities of apples being brought to this country the Furness Line, and that the fruit may be delivered good condition an elaborate system of mechanical ventilation has been fitted the holds and ’tween decks throughout.

Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 1 May 1913

Initially, Digby's cargo capacity and capability was largely to cater with the established apple and fruit trade of Nova Scotia which engaged, under a mail contract, a set number of sailings to England during the export season. It was only in the early 1920s, that the she was retrofitted with refrigerated capacity as the only ship so equipped on the Newfoundland route to develop an export trade for the island's fish for which she proved invaluable.

Digby had four holds (two forward and two aft), with two 'tween decks each, were specially lined and mechanically ventilated for the carriage of fruit and dairy produce homewards and general cargo to Canada. Her total cargo capacity was quoted at 6,500 tons. Unsual for the time, the 'tween decks additionally had side loading ports and she was possibly the first trans-Atlantic vessel with this feature. "All appliances for the rapid loading and discharging of cargo are of the most up-to-date description, eight powerful steam winches being fitted in conjunction with 12 derricks, provision being made at each mast for dealing with 15 to 20-ton lifts." (The North Star, 28 November 1912).

Beneath the shelter deck are two complete decks, the upper and mail; the 'tween deck height, to minimize broken stowage, being arranged to suit the diminsions of the casks in which the apples are transported.

The forward part of the ship is specially strengthened to withstand the impact of floating ice which may be encountered at certain seasons of the year off the Newfoundland coast.

The holds and 'tween decks are merely lined and not insulated for the transport of fruit, nor is any refrigerating machinery provided for this purpose. In order that the fruit may be delivered in good condition, an elaborate system of mechanical ventilation has been fitted to the holds and 'tween decks throughout, mechanical apparatus being placed in each of the uptake ventilators. Each of the latter is surmounted by a hood of special design. A compressed air engine, situated in the engine room, forces air into the uptake ventilators, and thereby causes a circulation of air through the fruit spaces. This arrangement has been devised by the builders themselves, and the air compressor has also been constructed by them

Shipbuilder & Marine Engine Builder, June 1913

|

| Builder's model of Digby updated with the post 1922 Furness funnel livery at the Hartlepool Maritime Museum. Note the side loading ports. Credit: Flickr |

Being post-Titanic, Digby's lifeboat fit, comprising two large boats on each side and one jolly boat in between them, carried at radial davits, was described as "being ample boat accommodation for all persons on board."

Designed for reliability more than speed, Digby's conventional machinery, again emulating that fitted to so many of Irvine's built cargo carriers of the period and constructed by Messrs. Richardsons, Westgarth & Co., Ltd., Hartlepool, consisted of a single cast manganese bronze screw driven by a triple-expansion engine with cylinders 28, 46 and 77 ins. with a 48-inch stroke. Steam was produced by three single-ended boilers (16.6 ft. dia. and 12 ft. long), with four furnaces each, with 9,142 sq. ft. of heating surface, working under forced draught, and producing steam at 180 lbs.

Digby burnt 42 tons of coal at full speed and carried 980 tons in her bunkers. At 3,150 ihp, her service was 12.5 knots, but averaged 14.38 knots on 12-hour trials and topped 15.18 knots.

It is worth considering that this machinery, including the boilers and all auxiliaries, remained in the vessel throughout her remarkable 52 years at sea. Moreover, she remained a coal burner throughout her British-flag career as Digby, Dominica and Baltrover.

|

| Builder's model of Digby, credit: shipsnostalgia.com, dlongly |

S.S. DIGBY

General Arrangement Plans & Side Cutaway

(from Schiffbau, August 1913)

(LEFT CLICK on image to view full size scan)

|

| First Class Boat Deck. |

|

| First Class Bridge Deck. |

|

| First Class Shelter Deck. |

Digby's passenger accommodation was just about the smallest in terms of capacity of any of her era, aside from cargo liners, reflecting a route that served a vital but small market and bearing in mind that Newfoundland's population at the time totalled fewer than 240,000 people and that faster and bigger liners served Halifax seasonally. Indeed, benefitting from the experience with Evangeline and Loyalist, her passenger capacity was a dozen berths fewer than the earlier pair.

First Class, totalling 58 berths, occupied most of the superstructure's Boat, Bridge and Shelter Decks, with open deck space on the Boat Deck and the two principal public rooms on Bridge Deck.

J.H. Isherwood described the First Class public rooms as "thoroughly Scottish in design, comfortable and compact, and life on board must have resembled that in a Highland country club, taken to sea."

The dining saloon was in a steel house forward on Bridge Deck, under the bridge and captain quarters, with small tables (but still the traditional bolted to the deck swivel chairs) for 36 diners. "The walls are finished in white enamel with a mahogany cornice, the furniture in the saloon also being of mahogany with electro-plated fittings. A piano is fitted in a recess at the fore end, designed to harmonise with the general decoration the saloon. extra number large brass sidelights are fitted, giving the passengers unobstructed sea view in practically directions." The room, as was common to many liners, served as a day and evening lounge outside meal hours with the tables not laid and in their natural green baize covered state. With higher ceiling height than elsewhere in the accommodation and with the large windows on three sides, it was a light and handsome room. Aft of the dining saloon was the main staircase and the foyer was arranged as an additional sitting room with banquette seating and table.

In its own house aft on Bridge Deck, and accessible only from the outside deck, was the social room, described as being a "handsomely furnished smoke room having grey marblework open fireplace and oak panelling to blend with chairs and tables." The panelling and decoration throughout being of light oak, and the settees, etc., upholstered in morocco leather. This had large portholes on the sides and facing aft, and its own bar.

Bridge Deck was encircled by covered walk around promenade deck with deck chairs, although given the rigours of Digby's route, it probably would have been more useful had it been glass enclosed for at least its forward extremities.

On Shelter Deck, amidships portside, was the small "ladies room" which was about the size of two cabins, and with two portholes, settees and card tables, and forward a cosy cabin lounge in the centre alleyway with armchairs and a recessed seating nook forward.

First Class accommodation was forward to amidships on Shelter Deck, consisting of 14 outside cabins and four inside ones, each with two berths and a settee. "The saloon staterooms are fitted with all the latest appliances looking to the comfort and convenience of travellers, these including latest designs with running water." None, of course, had private facilities and the ladies and gentlemen's public baths and toilets, were amidships on the port and startboardside respectively, and of unusually large size and with plenty of light and air from side portholes as well as from overhead opening skylights inboard on Bridge Deck.

|

| Second Class Bridge Deck poop house. |

|

| Second Class Shelter Deck aft. |

|

| Second Class Upper Deck aft. |

The Second Class were quartered in the poop, with its after end open to afford a small open promenade. Life here must, at times, must have been appalling. The route was a hard one, the Digby was no large ship, and though she soon earned the reputation of being an excellent sea boat the motion right aft and over the screw must have shaken the teeth out of many emigrants.

J.H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, July 1967.

With 32 berths, Second Class offered minimum rate passage but its location and facilities were indeed second rate, being far aft and over the screw.

At the after end of the vessel thirty-two cabin passengers find ample accommodation and the bath and lavatory arrangements of the most up-to-date description. The settings of the saloon dining room, like the apartments, are in white, the somber walnut woodwork showing in pleasing harmony with the mahogany tables and seating furniture.

Evening Mail.

The aft poop deck house on Bridge Deck contained the Second Class entrance with settees and serving as a small lounge and two outside four-berth cabins. Below was the dining saloon, "tastefully designed in mahogany, with oak panels," with galley and pantry outboard on the starboardside and the public gents and ladies' baths and toilets on the port side. The main Second Class accommodation was aft on Upper Deck comprising six four-berth cabins.

The Captain's quarters (office and separate bedroom), those of the Chief Officer and the chart room were forward on Boat Deck below the bridge and wheelhouse. Seamen, firemen and stewards were housed in the forecastle and engineers aft on Shelter Deck.

So it was with this staunchly built but otherwise unremarkable vessel that Furness Withy would re-enter the passenger, beginning a era of expansion that would see them, within two decades, operate some of the most successful and profitable liners of their time. It would also see Digby began a career that would extend beyond half a century of stalwart service through two world wars and under three houseflags and two national ensign which would establish her as the most enduring British deep sea merchantmen of her generation.

She only had about 18 months in service before war broke out, but this was long enough for her to prove herself both popular and paying.

J.H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, July 1967.

The year 1913 saw the All Red Routes linking Britain and her North American Dominions of Canada and Newfoundland and onwards to the Dominions of Australia and New Zealand and across the Pacific to Hong Kong infused with a veritible armada of new liners: Niagara, Empress of Russia, Empress of Asia, Andania, Alaunia and Digby. The proverbial runt of the litter, the little Digby would outlast all of them by a quarter of a century, beginning the career of the most enduring British-built liner of the Edwardian Age.

|

| Credit: Evening Telegram, 9 May 1913. |

Digby (Capt. J.H. Trinick) departed Liverpool at 2:00 p.m. on 8 May 1913 on her maiden voyage to St. John's and Halifax with 30 First Class and 15 Second class passengers, with an anticipated arrival on the 14th. The following day, the Evening Telegram reported that: "ss Digby, seven days out from Liverpool, is expected to arrive any moment. A wireless message from the ship was expected to come via Fogo, owing to the Cape Race station being out of commission, but nothing from her received up to noon day."

|

| Credit: Evening Telegram, 16 May 1913. |

Digby actually arrived at St. John's on 15 May 1913, 7 days 7 hours out of Liverpool, as reported by the Evening Telegram the following day:

At nine o'clock last night, the new Furness Line steamer Digby, which is scheduled for two more trips on the Liverpool-St. John's and Halifax route, carrying mails and passengers, steamed into port. The passage occupied seven days, seven hours. The ship left Liverpool at 2 p.m. Thursday May 8th. Exceptionally good headway was made for about four days of the voyage, the ship making fourteen knots, but after that dense fog was met and consequently the ship was detained. At 3 p.m. yesterday she was eighty miles off this port. Conditions were then favorable and the Digby finished her maiden voyage in splendid style. The Digby brought 28 packages of mail matter. 500 tons of cargo, and as passengers:—Dr. I. G. Duncan. Rev. H. Uphill. S. Daish and J. Deatherby. The ship is about equal in point of accommodation to the Mongolian, though can steam faster as she is new. The Digby is fitted with modern conveniences, and will afford comfort to travellers. The most competent and experienced stewards are attached to ihe ship.

Capt. Trinick who is in command of the Digby, is well known here having been a former master of the Furness liner Shenandoah which used to run here. Chief Officer is C. S. Emmett, Surgeon Dr. H. Godden Cole, and Chief Steward F.B. Webb, who came here several years in the Almeriana and Tobasco. On Tuesday night last an interesting concert was held on board the ship. Dr. Duncan presided, and Rev. H. Uphill contributed selections. The sum of £2. l s. 1d. was taken up for the Marine Disaster Fund. All monies collected are left to Chief Steward Webb for distribution to whatever purpose he sees merits the amount most.

A reception will be held on board the Digby this afternoon. and she sails for Halifax tomorrow.

Aboard were 30 saloon and 15 Second class passengers of which the Evening Telegram noted, "On the Digby are some 30 young Englishmen, all mechanics, bound out to the Northwest of Canada. They should do well there in a country, just beginning development, and where skilled labor is at a premium."Among her cargo soon to be advertised in local St. John's stores were children's white canvas and kid footwear and a shipment of the latest New Hudson cycles.

A welcoming reception aboard that afternoon was attended by Major Davenport, representing His Excellency the Governor, Colonial Secretary Watson, leading businessmen of St. John's and members of the Legislature and Legislative Council. "Afternoon tea was served in capital style and Capt. Trinick proved a most entertaining and kindly host."

Digby proceeded to Halifax on 17 May 1913 where she docked at No. 3 Terminal Piers on the 19th.

|

| Credit: The Evening Mail, 21 May 1913. |

|

| Credit: Evening Mail, 23 May 1913. |

After full inspection of the vessel it stands as the general expression of opinion that for the carriage of apples and other good indigenous to Nova Scotia, she exceeds all other and aptly the merits the ideal besides enchancing the shipping of Halifax.

Evening Mail, 23 May 1913

On 22 May 1913, Digby's officers and Furness Withy officials in Halifax including Capt. Harrison, marine superintendent, Harry C. DeWolf, George M. Brew and William B. Spencer, of the passenger department, hosted a reception aboard from 3:00-6:00 p.m. attended by the Lt. Governor MacGregor and "scores of representative citizens of Halifax" who had the "full opportunity to admire at close view what stands as a worthy precursor of three similar craft proposed for the transatlantic route to Halifax. That Furness, Withy and company were justified in building a vessel so well adapted for the transportation of maritime province products overseas was amply demonstrated in the numerous express of admiration for her neatness in design and general excellence of equipment."

Particular interest was attached to the elaborate an comfortable passenger accommodations, and the completeness and finish with which these have been wrought evoked much enthusiasm."

With this ship and the new ships to follow, we are able to do something we never did before, and that is to cater to the passenger trade with a good assurance of success. The voyage from Halifax to Liverpool, calling at St. John's, Nfld., by the Digby, will take 9 days, just long enough for an enjoyable sea trip, and it will be made with as great comfort to passengers as they get on many of the big liners. We shall have accommodatuon for 60 first and 40 second class passengers, and we have the guarantee of our head office that the catering, that is the meals, etc., will be splendidly done. With the growing inclination of Maritime Provinces people to see the land of their forefathers, and the reasonable rate at which they can buy a ticket, I shall be greatly surprised if we do not work up quite a large passenger business with the next year or two. For a matter of $260, a man can go to England and return first class, and have a three weeks holiday in London, at a comfortable hotel. I am in hope that at the next sailing of the new ship from Halifax, early in July, we shall have at least a few of the people who have been waiting for just such a splendid chance of going to England, as this one affords, and every one who goes will be an influence to send others. "

Interview with John Furness,

The Maritime Merchant and Commecial Review, 22 May 1913

On 23 May 1913 Digby was opened for a visit and reception by the Women's Council of Halifax.

|

| Credit: Evening Telegraph, 13 May 1913. |

Digby left Halifax at 9:00 p.m. on 26th May 1913 for Liverpool via St. John's where she arrived on the 27th at 6:00 p.m. after a passage of 43 hours 30 mins. Among her passengers for Liverpool was His Grace Archbishop Howley and 120 tons of cargo to land including cheese and potatoes. Digby departed for Liverpool on the 29th, docking there on 6 June.

On her second voyage, Digby cleared the Mersey on 14 June 1913 and enjoyed good weather until half way across when a strong westerly gale was encountered. Her progress was further hindered by a thick, persistent fog 300 miles off St. John's and ice bergs reported nearby which had her at a standstill for two days. Digby finally arrived at St. John's at 5:30 p.m. on 22 June 1913, with 450 tons of cargo and 19 First Class and 18 Second Class and 24 passengers in transit for Halifax, among them J.E. Furness, Director of Furness-Withy Co.. A very strong current made it difficult for Digby to turn once she had cleared her pier at St. John's on the evening of the 23rd, bound for Halifax where she docked on the 25th.

|

| Credit: The Evening Mail, 26 June 1913. |

Timed for forty-two hours rapid steaming from St. John's to Halifax on the last leg of the voyage over from Liverpool, the handsome Furness flyer Digby sailed up the harbor at one o'clock yesterday afternoon after an eleven day passage across the Atlantic. She had a good complement of passengers and her holds held a great quantity of cargo.

The vessel is intended to carry general cargoes from this country and bring back fruit, principally apples and dairy produce. If the trade develops, as anticipated by the late Lord Furness, she will be but the first of a greatly improved type of vessel to be out on this service.

Evening Mail, 26 June 1913

A testimonial by the passengers was published in The Evening Mail 28 June 1913: "We the passengers on the steamer Digby, on this voyage from Halifax to Liverpool, do hereby express our great satisfaction at the steadiness, speed and comfort while crossing the Atlantic, and also take this opportunity of expressing to the captain, officers, waiters, and crew, our gratitude for the very great kindness, politeness, attendance an agreeableness to all those on board."

Addition to Halifax Line, So far as our Canadian business is concerned, you will see we have added a new passenger and cargo steamer, the s.s. Digby, to our Halifax Line, and it is the intention of the Company to build two further and similar vessels for the same service. We have added to our business at Montreal by the establishment of a weekly service of steamers to Hull, which is yielding very satisfactory results, and the opening of our own office in Newfoundland will largely contribute to the efficiency of our general organisation. We have, as you know, our own freehold wharf and offices at Halifax, and we have now under contemplation the erection of a wharf at St. John's, Newfoundland, to provide for the larger class of steamers which we now employ in that service.

statement by Sir Stephen Furness at 22nd annual meeting, 26 July 1913

Into the summer of 1913, Digby settled into service with a voyage every six weeks from Liverpool, most of them routine and uneventful. Her passenger trade was slow to develop at first, with 15 passengers for her 17 July departure from the Mersey which proved her fastest yet, making St. John's seven days later despite fog encountered on the later portion. The eastbound crossing was faster still, Digby returning to Liverpool on 12 August, just six and a half days from St. John's. Her next sailing, on 18 August, had 27 First and 25 Second Class passengers. With good weather that late summer, she put in a fine six-day passage from Liverpool, arriving at St. John's on 27 September with 10 First Class, 18 Second and 500 tons of cargo for the port.

Asked how he felt about the success of their new ship, the Digby, during the present season, Mr. Furness told us that he felt most encouraged. She had done splendidly and he hopes next seas to have another boat of greater tonnage and more passenger accommodation for the same route. 'There is a big passenger travel between Newfoundland and the Old Country,' said he, 'and I think we have been getting most of it since the Digby was put on the route.'

Interview with John Furness, Manager, Halifax, in The Maritime Merchant and Commercial Review, 6 November 1913.

Digby's route was the most ardurous and challenging of all North Atlantic tracks with fogs off the Grand Banks in early summer, ferocious gales in winter and towering ice bergs in the twos, tens or hundreds and epic ice fields stretching over hundreds of miles that could be encountered from November through June. Through good, prudent seamanship and the experience of her officers and crew, Digby made every single crossing safely and sometimes assisted those not so fortunate.

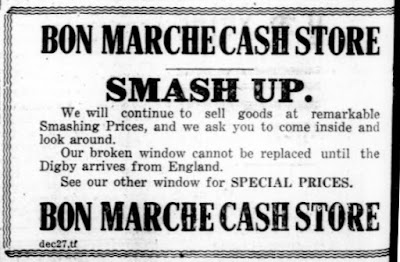

When Manchester Commerce (1899/5,363 grt), which sailed from Montreal in late October 1913, collided with an iceberg in the Strait of Belle Isle, she was able to make it to St. John's on 4 November where arrangements were made to repair her considerable damage locally, entailing replacement of her entire bow. An order, sent by cable and of over 300 words, went to Irvine's Shipbuilding and the necessary parts begun at once, including a new stem and 17 frames, all bent and punched and ready for installation, were shipped aboard Digby at Liverpool. She sailed on 29 November and reached St. John's on 7 December after an eight-day passage with "strong westerly gales experienced during the voyage." Repaired, Manchester Guardian left St. John's on 16 January 1914.

|

| Credit: Maritime Merchant and Commercial Review, 26 February 1914 |

1914

On her first voyage of the New Year, Digby left Liverpool 7 January 1914 and had a classic winter crossing from press accounts: "The Furness liner Digby, Capt. Trennick, 9 days from Liverpool, arrived at 6:30 p.m. last evening, after a stormy passage. Moderate weather prevailed at the start, but the latter half of the voyage the conditions were most unpleasant. For four days there were strong westerly gales and for the couple of days keen frost and heavy snow. She brought 100 tons general cargo, two passengers, Mr. Peyton and Miss Miller, and two for Halifax." (Daily Mail, 17 January 1914). The Evening Telegram added that "the trip was stormy throughout and as the ship was lightly laden and consequently she was knocked about badly." Among her cargo was "one of the largest shipments of films ever brought here at one time direct from Liverpool" which was advertised in local St. John's papers just in time for those long winter evenings. When Digby came into Halifax on the 20th, she was one of the first ships to use the new "Million Dollar Concrete Pier," Terminal No. 2.

In reporting on 21 January 1914 that Digby would continue service throughout winter, The Evening Telegram, added, "All who travel by the boat speak in highest terms of the accommodation afforded and of the courtesy of Capt. Trinick and his officers."

|

| Credit: Maritime Merchant and Commercial Review 9 April 1914 |

Even the short run from Halifax to St. John's could prove difficult in winter. En route to Liverpool, via St. John's, Digby embarked 10 passengers at Halifax on 14 March 1914 transhipping from the inbound Empress of Britain, who were destined for Newfoundland. It proved a most tedious and protracted passage with strong head winds and when she was close to Cape Race, Dibgy ran into "heavy slob ice, accompanied by fog, necessitating skillful and careful navigation of the ship," and she did not come into St. John's until 1:00 p.m. on the 17th. Among those sailing from St. John's for Liverpool on the 18th were H.E. the Governor of Newfoundland and Mrs. Davidson, and John E. Furness. Digby arrived on the Mersey on the 27th and underwent her first annual drydocking.

|

| Credit: Evening Mail, 9 May 1913. |

On her longest voyage to date, Digby sailed from Liverpool 25 April 1914. Fine weather was enjoyed until 1 May when, 320 miles from St. John's, she ran into dense fog and then encountered an epic ice floe. "Captain Trinnick stated that at noon on Saturday they received a wireless from Cape Race, informing them that the coast was blocked with ice. They were then 170 miles off St. John's and to avoid the ice the ship proceeded as far south as the Virgin Rocks, scouting around the floes. They continued this for five days, steaming slowly, as it as foggy during the greater part of the time, and were finally able to enter St. John's harbor on Friday [7th], having completely circled the ice which had caused the vessel to cover some 500 miles more than she should have had she been able to follow her usual course." (Evening Mail 12 May, The ship had actually arrived off St. John's on 3 May but dense fog preventing her from entering port until the wind changed. Digby finally docked at 11:00 a.m. on 7th with 800 tons and 10 passengers.

|

| Credit: Evening Telegraph, 8 May 1914. |

In all, it had taken her 13 days to reach St. John's and even on arrival, Digby had to anchor in the stream waiting for tugs to tow several growlers lying close to the pier, delaying her docking by another hour. She finally reached Halifax at 11:00 a.m. on 11 May 1914 with only two passengers to land there, one of whom was John Furness, returning from a business trip in England. She brought in 800 tons of cargo which had to be unloaded by local boys when the dock workers were absent attending a meeting of union longshoremen.

|

| Furness adveritsement showing the fares c. 1914. Credit: Newfoundland Quarterly, summer 1914. |

Digby sailed from Liverpool 3 July 1914 and arrived St. John's on 10th after an eight-day crossing with 500 tons of cargo and several Salvation Army officers returning from Congress being held in London. On the return crossing, the Red Cross liner Stephano and Digby ran a veritable race to St. John's as reported by the Evening Telegraph, 17 July:

Stephano beat Digby to Halifax.

When the red cross liner Stephano arrived at Halifax from St. John's nfld at five o'clock yesterday morning, her officers were much elated over the fact that they had knocked three and one-half hours from the time of the Furness liner Digby with which they had raced from port to port. The Digby left st john's at 1.30 p.m Saturday and the Stephano sailed at 3.15 p.m arriving at Halifax at 5 a.m Monday morning, the Digby arriving two hours later. The Stephano passed her rival at 9 a.m Sunday and the two ships kept with in sight of each other the rest of the voyage.

Considerable betting was done on both ships the second engineer winning the pool among the officers of the Stephano.

In my remarks last year I referred to the acquisition of the new passenger steamer Digby, which was constructed at Irvine's Shipyard. This vessel has considerably enhanced our reputation in the Canadian and Newfoundland trade, having carried many distinguished passengers, including the Premier of Newfoundland. The tender for the construction of our new wharf and warehouses at St John's, Newfoundland, has been let; the work is proceeding satisfactorily, and we hope to be in possession of the premises during the present year. As mentioned, this development was necessary owing to the increased size of our steamers, and when the wharf and warehouses are completed they will be the finest and most up-to-date property of their kind in the colony.

Sir Stephen Furness, 23rd Annual Meeting statement, 25 July 1915

|

| Credit: Maritime Merchant and Commercial Review 30 July 1914 |

Digby left Liverpool 1 August 1914 and was about midway across the Atlantic when word came that Great Britain and the Empire had declared war on Imperial Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Newfoundland, with its population of only 240,000, would contribute no fewer than 12,000 men to the Royal Newfoundland Regiment and suffer 1,281 dead and another 2,284 wounded whilst others served in the Royal Navy and Merchant Navy.

For Digby, it was, for a time, business as usual, and she arrived without incident at St. John's on 10 August 1914 after a quick passage of 7½ days. Homewards, she docked at St. John's on the 20th after a 45-hour run from Halifax and her cargo for Liverpool included cod and seal oil. Among those sailing from St. John's the following day were "Mr. D. Simmons, sailing to join a Yeomanry Regiment, Messrs. Dyke, Miller, Barnes, Shaw and Learmouth also left in answer to the call to arms." (Evening Telegram 22 August 1914).

|

| Credit: Maritime Merchant and Commercial Review, 10 September 1914. |

Digby arrived St. John's at 5:00 p.m. on 15 September 1914 at 5:00 p.m. after a smart passage from Liverpool of 7 days. "During the latter part of the voyage the ship met with considerable fog which retarded progress." She had 400 tons of cargo and 9 First and 1 Second class passengers for Newfoundland and 30 First and 8 Second in transit for Halifax, embarking 14 additional First Class passenger for Nova Scotia.

|

| Credit: Evening Telegram, 16 September 1914. |

...keen interest existed among the passengers on board the Digby and Carthaginian as well as among the crews both ships left liverpool yesterday week in the afternoon the Digby got away from the Liverpool pier ten minutes before her opponent the latter however caught up to the former before getting clear of the mersey. The Carthaginian kept the lead all that night until the following day Wednesday when the digby passed her and never sighted the Carthaginian afterwards beating her by fifteen hours.

Evening Telegraph, 16 September 1914

After a 42-hour passage, Digby docked at Halifax on 18 September 1914.

|

| Sailing announcement for what would be Digby's last commercial crossing for the duration, showing London not Liverpool as the departure. Credit: Canadian Gazette, 8 October 1914. |

On what would prove her final commercial voyage "for the duration," Digby sailed from London on 15 October 1914 with only 11 passengers, a small quantity of mail and 550 tons of cargo. After a 7½-day passage, she came into St. John's on the 23rd. "During the passage heavy weather was continuous but for which a quicker run would have been made." (Evening Telegram). Among her cargo was 8,000 yards of flannel which will be distributed to various centres of the Woman's Patriotic Association for making into garments for Belgian refugee children. Proceeding to Halifax, Digby commenced her eastbound crossing from St. John's on the 27th with 16 First and 11 Second Class passengers.

In spite of the fact that she was considerably smaller than most of her consorts in the cruiser squadron, she proved herself a great success under the White Ensign until November, 1915. Then, on account of American feeling against the blockade maintained by the British Navy, it was decided that these operations should be international in order to show that all the Allies were concerned in them. The Digby was accordingly transferred to the French flag and under the name of Artois she continued on the same work until the United States came into the War, when there was no need to trouble further over the matter and she was transferred back to the White Ensign.

The Baltic Trader, Frank C. Bowen

Digby and her Merchant Navy consorts, one of the finest assemblages of ocean liners ever, some like her almost brand new, went to war. She and so many others would do so as fighting units of the Royal Navy and Digby would not only be among the smallest armed merchant cruisers but one of two to serve under two flags, on tough, tedious and arduous duty maintaining the Northern Patrol as part of the famed 10th Cruiser Squadron.

1914-1919

Upon arrival in London (Surrey Commercial Docks) on 17 November 1914, Digby was immediately requistioned by the Admiralty as an armed merchant cruiser. Her advertised sailing for the 28th was cancelled. As such, she would be one of the smallest vessels so employed and reflected wartime experience in employing large express steamers in the role which proved less than satisfactory and in the interdiction of neutral flag shipping in the shipping lanes between Scotland and the Faroe Islands, the equally inadequate and elderly Edgar-class elderly cruisers originally used. Ships like Digby with good armament, large coal capacity and tough seaboat qualities would prove ideal for the role.

Even so, Digby required some fairly extensive alterations and this work was carried out in London. This included extending the Bridge Deck forward and aft of the superstructure to provide mountings for her main offensive armament of a pair of 6-inch naval guns fore and aft plus one each in the prow and stern, fitted with gun shields, and the fitting of the necessary ammunitions hoists and magazines below decks. She was also fitted with a pair of lighter six-pounder guns. As such, she was pretty formidably armed for a 3,800-ton, 350-long vessel engaged in merchant ship interdiction duties. Like most AMCs, a considerable amount of fixed ballast was taken aboard to compensate for the lack of cargo although extra coal was shipped to extend her time on station. She carried 1,350 tons of coal giving a cruising radius of 8,500 miles at 10 knots, 8,000 miles at 12 knots and 4,500 miles at full speed (14.5 knots).

H.M.S. Digby was commissioned, depending on sources, either on 22 November 1914 or 21 December, the later date possibly being more likely given the time, even under wartime expediencies, to convert her to her new role, under Commander Richard F.F.H. Mahon, and assigned pennant no. M.83. Her compliment comprised 23 officers (3 Royal Navy, 19 Royal Navy Reserve and 1 RNVR) and 280 ratings and other ranks composed of Naval Reservists and Merchant Navy personnel.

|

| Rare seaman's cap tally for H.M.S. Digby. Credit: eBay auction photo. |

The date of Digby's first deployment is uncertain but she was included in an official list of the "Reconstituted 10th Cruiser Squadron" (following the replacement of the Edgar-class cruisers) dated 24 January 1915 and published logs dating from March 1915 onwards shows her already well "on the job" Of the 60 total armed merchant cruisers (AMCs), half (33 to be precise) served with the 10th Cruiser Squadron at various times.

In what was the longest continuous naval operation of the war (August 1914-December 1917), the 10th Cruiser Squadron maintained the Northern Patrol which covered the shipping lanes between northwest Scotland, Iceland and Greenland. Intercepted ships which did not fly the prescribed recognition flags or signals were boarded, itself often a hazardous task in all sorts of sea and weather conditions by a boarding party in open boats, and inspected for suspected contraband of war (the definition of which was decided upon and changed by the Allies as the war progressed), mails and parcels searched and any passengers questioned and papers checked especially with a view to intercept German nationals returning to the Fatherland to enlist. Vessels found to have contraband were put in the charge of a prize crew and taken to a British port, usually Kirkwall, for further inspection and unloading if necessary.

On a given day, 4 July 1915 for example, the 10th Cruiser Squadron was composed of 24 vessels: Alcantara, Alsatian, Ambrose, Andes, Arlanza, Cedric, Changuinola, Columbella, Digby, Ebro, Hilary, Hildebrand, India, Mantua, Motagua, Orcoma, Oropesa, Orotava, Otway, Patia, Patricia, Teutonic, Victorian and Virginian.

Like any patrol operation, Digby and her consorts and their crews had long stretches of monotony and busy periods but the worst aspect of the duty was the long periods at sea in often atrocious weather conditions and the ships could be on station for a month or more before returning to Glasgow for coaling and reprovisioning. It was hard duty on the ships themselves and Digby, staunchly built for her peacetime trade, was ideal for the role.

As an example of a busy day for Digby and her crew is this log abstract in March 1915:

25 March 1915PatrolLat 59.58, Long -9.556.30am: Observed steamer6.50am: Stopped; exchanged signals with SS Largo (Norwegian) in charge of prize crew from HMS Virginian6.60am: Ordered them to proceed7.10am: Proceeded7.30am: Exchanged challenge with HMS Otway.9.05am: Signalled SS Sir [?] (Norwegian) of Bergen, westward bound.9.25am: Stopped9.30am: Boarded SS Avona of Bergen (Norwegian)9.40am: Course and speed as required for circling round Avona10.20am: Put prize crew on board Avona10.30am: Avona proceeded for Kirkwall10.40am: Proceeded3.40pm: Sighted steamer4.30pm: Stopped; lowered port sea boat and boarded SS Boden (Swedish); course and speed as required for circling5.00pm: Put prize crew on board5.15pm: Boden proceeded to Kirkwall; hoisted sea boat10.50pm: Sighted steamer on port beam11.15pm: Stopped; boarded SS Helman

On 13 May 1915 Digby returned to Glasgow for coaling and restoring and left on the 20th and returned on the 16 June for the same purpose and this was the usual routine with ship on continuous patrol for four weeks followed by a week in home port for coaling. In July, Digby was finally drydocked at Prince's Graving Dock no. 3, Glasgow, her underwater hull, after cleaning, receiving " British Antifouling Composition consisting of Red Navy Protective, one coat, and Red Navy Antifouling, one coat." Back on duty, Digby was detailed to sail to Reykjavik, Iceland, arriving 3 August 1915 and commencing patrols off the Island and coaled at sea from two colliers.

Commander Arthur G. Warren assumed command of Digby on 27 August 1915.

Doubtless effective, the British blockade and interdiction of neutral ships, one of the privileges of possessing the greatest navy in the world, was a public relations headache for Whitehall, arousing increasing resentment from the governments, shipping owners, passengers and shippers of the most affected neutral countries: Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the United States and even after Lusitania, American sentiment was decidely cool to Britain and more so when American ships were stopped on the high seas by British ones. It was therefore decided that the composition of the 10th Cruiser Squadron should be "Allied" rather than British and it was arranged, rather cynically and extemporaneously, to transfer two British AMCs to the French Navy: Oropesa and Digby. Each would be manned by French crews and officers but remain units of the 10th Cruiser Squadron under Britsh command, although in the case of Digby her Chief Engineer was seconded in an advisory capacity for several months.

H.M.S. Digby arrived at Glasgow, on 29 October 1915 and sailed on the 13th for Devonport (16) where she disembarked most of her crew before departing for Brest on the 22nd where docked on the following day. At midnight on the 24 she was official handed over to the French Navy. Capt. Paul Marie Gabriel Amédée de Marguerye assumed command. The ship was renamed Artois.

The Artois was given as Captain, Paul Marie Gabriel Amédée De Marguerye, a distinguished French naval officer and sent north to rejoin the 10th Cruiser Squadron once again. She did not have the easiest of starts as she was expected to operate as the English crews did, and the French were not aware of the requirements of the job. With help from the Admiral and the officers of his Flagship, HMS Alsatian, the crew of the Artois got the hang of things and proceeded to operate the blockade as required.

They stood by a dismasted sailing vessel and, eventually, towed the vessel into Stornoway – to the great relief of all! Another incident that occurred was when the Artois was chased by a submarine which she eventually evaded. The Auxiliary Cruiser Artois continued the work of the blockade as she did in English Naval Service. She met and challenged other ships, exchanged greetings with her colleagues in the 10th Cruiser Squadron and avoided the German submarines which were a menace. These submarines, apart from sinking ships, were used to lay mines in the approaches to Britain and around British ports.

http://www.hhtandn.org/notes/811/ss-digby-in-world-war-one

Once she had rejoined the 10th Cruiser Squadron, Artois' duties and routine were unchanged from her Digby days. But even the famous Squadron could not be everywhere and in November 1916 came the infamous breakout of the German raider Möwe which passed through the gap between Ebro and Artois patrol area north of the Faroes and went on a rampage, beginning with the sinking of the Lamport & Holt liner Voltaire, for New York, and the Mount Temple the following day, tragically laden with a cargo of 710 horses.

With the entry of the United States into the war in April 1917, the artifice of the Anglo-French 10th Cruiser Squadron could be ended. On 19 July Artois was returned to the British at Glasgow, Commander Hubert S. Cardale assuming command. Her name was retained and as H.M.S. Artois (MI.55) she sailed from Glasgow on her first patrol back under the White Ensign on 7 August. Two days later at Lat. 57.7 Long. 14.7 two torpedoes were fired at the ship, one passing ahead and one astern. She dropped a depth charge but it failed to explode.

Less exciting but more typical of the sometimes monotonous and rough conditions endured on endless days "on patrol" is the log abstract for 23 August 1917:

At seaLat 63.0, Long -15.0Ship pitching heavily at times to high sea and swellShip pitching heavily at times to high sea and strainingHigh head seaShip pitching heavily falling off during heavy squalls.

|

| Rare wartime view of H.M.S. Artois in "dazzle" camouflage, c. 1917. Credit: teesbuiltships.co.uk, Richard Cox |

On 17 September 1917 Artois sailed from Glasgow on her final patrol for the 10th Cruiser Squadron which included a call at Loch Ewe for coaling 12-14 October. The Northern Patrol was ended and the AMCs were reassigned as convoy escorts, including Artois which meant a "homecoming" for the former Digby on a voyage to Nova Scotia in October 1917. She sailed from Loch Ewe on the 14th and arrived at Sydney, N.S. on the 24th and left there on the 29th escorting a convoy to Belfast, reached on the 10th.

On 25 November 1917 Acting Captain Vernon S. Rashleigh assumed command. In April 1918 H.M.S. Artois was given a new pennant no., MI.33, and continued her convoy escort duties for the remainder of the war.

H.M.S. Artois was paid off on 6 January 1919 and turned over to Furness Withy.

|

| Digby as shown in a late 1918 Furness Withy advertisement with the revised Furness funnel colours she wore in 1914 and 1919-21. |

The Furness Line provides the regular connecting link between Great Britain and the oldest overseas Dominion, Newfoundland. Since the War this service has been provided by the steamers Digby and Sachem, two most comfortable and popular ships, each with accommodation for about seventy cabin passengers and making the passage in about seven days. They carry the mails to and fro as well as general cargo.

The Furness Line has been associated with Newfoundland for the past thirty years and throughout that time has not failed-- not even during the difficult war years-- to maintain this service which enables the Newfoundlander to market his products of Fish, Oil, Timber, Pulp, etc. in Europe and obtain in lieu there of the dry goods, hardware, fruits, etc. which he requires to import.

Furness Withy brochure, c. 1925

An almost new ship whose career had been interupted by war, Digby was by no means unique for her era. She was, however, one of the first to resume full commercial service. Moreover, having reintroduced Furness to trans-Atlantic passenger service just before the war, Digby would be in the vanguard of a true inter-war heyday for Furness liners and expanded routes throughout the Americas from Bermuda (Furness Bermuda Line created in 1919), South America (Prince Line) and eventual new and bigger sisters for the Newfoundland/Nova Scotia run.

1919

After an absence of several years the Furness liner Digby will once again visit Halifax, and is expected to leave Liverpool before the end of the present month. She will re-open the pre-war passenger service which the Furness, Withy Company conducted between Liverpool, St. John's and Halifax, and will be followed by the Sachem. They will also take the place of the steamers Rijsbergen and Gracianna, and will addition to cargo, carry passengers, not only between Liverpool and this port, and also between Halifax and St. John's, and for which both steamers have excellent accommodation.

The Evening Mail, 7 March 1919

Built in a Furness-owned yard, Digby would be refitted for post-war commercial service by another "house" shipyard, the Rushbrooke docks at Queenstown of Messrs. Johnson and Perrott of Cork, acquired in November 1917 which henceforth would be used for annual refits for much of the Furness fleet going forward.

Although Digby would be refurbished to pre-war condition (save for the addition of 5,040 cu. ft. of refrigerated cargo space), the services to Newfoundland reflected post-war conditions, mainly the end of Allan Line's services there with it now part of Canadian Pacific and the mail contracts were not renewed. Plans to build two more Digbys, shelved during the war, were not revived after it given high shipbuilding costs, uncertainty of trade and the more pressing need to replace war losses. Instead, the Warren Line's Sachem was added to the route to partner with Digby. Dating from 1893, the 5,204-grt, 11-knot, 59-berth Sachem was the typical "stop-gap" that would wind up soldiering on for six years.

On 26 February 1919, Digby left Queenstown for Liverpool to load for her first post-war voyage. In command was Capt. H.W. Chambers, who had commanded Durango during the war and was credited with sinking a U-Boat on 26 August 1918 before his own vessel was sunk, for which he awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

|

| First post-war sailing list. Credit: Dundee Courier, 11 March 1919. |

Upon re-entering service, Digby uniquely figured in the pioneering trans-Atlantic flights that captured the world's imagination in 1919.

In April 1913, the year Digby entered service, the Daily Mail offered a £10,000 prize for the first aviator to the cross the Atlantic from North America to Great Britain or Ireland in 72 continuous hours or less. The contest lapsed during the war, but with the enormous advances in aviation made during it especially in Britain and the development of long range bombers, was revived with great intensity by 1919. Offering the shortest route to the British isles, Newfoundland became the epicenter of competing efforts by spring 1919 and as the only line with direct services there, Furness played an important role in the transportation of the aeroplanes, equipment and men to create makeshift bases near St. John's. There were four main entrants in the competition: Sopwith (Hawker and Grieve), Vickers Vimy (Alcock and Brown), Martinsyde (Raynam and Morgan) and Handley Page (Brackley, Kerr, Gran, Wyatt, Arnold and Clements).

With twenty-three passengers for St John's, Nfld., the Furness liner Digby sailed on Thursday night last week for that port and Halifax. This is the first trip of the Digby since October, 1914, when she was requisitioned by the British Government and used as an auxiliary cruiser. She was recently released and after undergoing some repairs has been again placed on the service.

Shipping: A Weekly Journal of Marine Trades, 29 March 1919

Resuming the Furness Withy service to Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, Digby departed Liverpool on 20 March 1919 with 42 passengers among whom were the Australian aviator Harry C. Hawker and Lt. Cmdr. MacKenzie Grieve (Sopwith), RNAA Major C.W. Fairfax Morgan, the navigator for Major Frederick Raynham's trans-Atlantic flight in a Martinsyde triplane. Also on board were returning men of the Newfoundland Battalion including Tommy Ricketts, the youngest recipient of the Victoria Cross. Among her cargo were two enormous packing cases containing the Sopwith Atlantic biplane for Hawker and Grieve's planned trans-Atlantic flight from Mount Pearl set for 12 April.

Although flying the Atlantic offered its own considerable challenges, so did the more familiar early spring ocean crossing. When some 120 miles from St. John's on 27 March 1919, Digby encountered impassable ice floes which prevented her from coming into the port. With the deadline for the flight not far off, Digby was instructed to proceed instead to Placentia Bay on the south coast where she came anchored off St. Bride's Harbor on the 28th at 5:00 p.m. There she rendezvoused with the Red Cross Line's Portia on to which she loaded the crates containing the aircraft and equipment and the airmen who would proceed overland by train to St. John's. As for Digby, she proceeded direct to Halifax where she arrived on the 31st.

|

| Sailing notice for Digby's first eastbound crossing from Halifax. Credit: Evening Mail, 2 April 1919. |

Digby sailed from Halifax on 8 April 1919 and came into St. John's on the 10th at 11:30 p.m. after a "fair run of 53 hours," encountering a large number of bergs en route but no field ice until Cape Race when she encountered a heavy string which caused her "nurse along slowly." She landed 1,700 tons, 22 passengers and had 10 in transit for Liverpool. Capt. Chambers was presented with a set of pipes by the St. John's Board of Trade during the first post-war call. Digby left St. John's on the 12th for Liverpool with 47 passengers.

|

| Digby's running mate, the former Warren Line steamer Sachem, coming into a snowy St. John's. Credit: eBay auction photo. |