As the Port Kingston, one of the most beautiful passenger ships in the world, and the leading vessel in that great fleet which has done almost more to imperialise Great Britain than any fleet of which I know-- the fleet of Elder Dempster-- dropped anchor in Port Royal one burning morning last December, there came upon me a sudden realisation of what the British Empire really means.

Raymond Blathwayt, Vanity Fair, 14 July 1909.

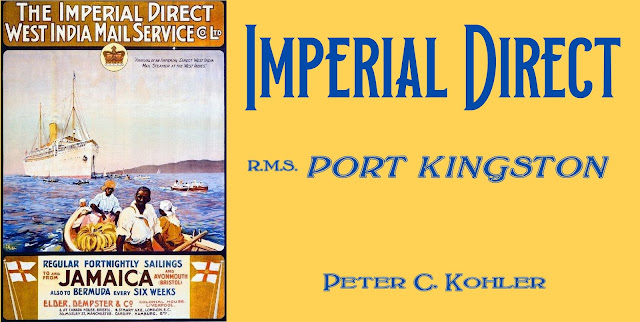

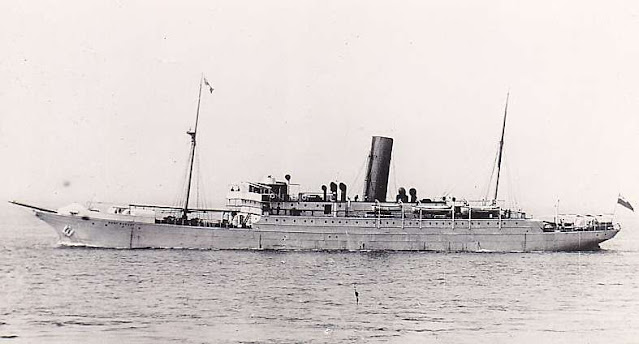

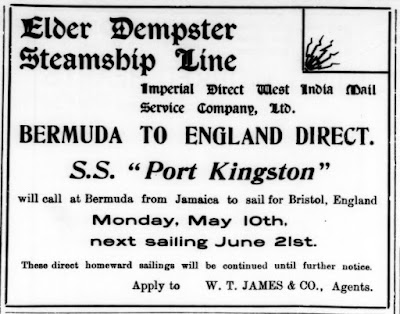

The pride and joy of Sir Alfred Jones, that most ardent of all shipping magnates and Empire builders, the handsome Port Kingston was, he readily admitted, "built in excess of requirements" for that ancient colonial route from England to Jamaica. Indeed, she was not exceeded in size on the "Banana Run" for nearly half a century. Flagship of the Imperial Direct West Indies Mail Service, pioneer of exporting the West Indian banana to Britain, she was the first luxury express liner on the West Indies run.

R.M.S. Port Kingston, a comparatively short-lived failure on her original service, nevertheless went on to another two decades of successful duty on another empire sealane. But here our focus is on her original route-- Bristol & Bananas-- when Port Kingston was the undisputed Greyhound of the West Indies, gleaming white and buff, coursing between Kingroad and Kingston.

|

| R.M.S. Port Kingston (1904-1911), largest and finest British "Banana Boat" until Golfito of 1949. From the cover of Imperial Direct Guide to Jamaica, 1906. |

I believe that the British race is the greatest of the governing races that the world has ever seen... It is not enough to occupy great spaces of the world's surface unless you can make the best of them. It is the duty of a landlord to develop his estate.

Joseph Chamberlain, Colonial Secretary

One of the most identifiable, evocative and specialised of vessels was The Banana Boat-- white in paint, fleet in speed, fine in form-- coursing from languid tropics to northern climes carrying one of nature's most perfect foods to green grocer, market and table. The banana, fast to grow and easy to harvest, is one of the most demanding of cargoes to ship. The story of the British Banana Boat, in particular the biggest and best of them for close to half a century-- R.M.S. Port Kingston-- begins with a verdant Caribbean island, an Empire Builder and one of Britain's last great Merchant Adventurers.

The banana is a comparatively modern addition to the larders of the Northern Hemisphere, dating only to the last quarter of the 19th century and owing its ready availability to the development of the steamship and the perfection of means to transport a delicate perishable commodity over thousands of ocean miles.

Time and distance mattered most in the early days of the banana trade and was initially centered on the United States Eastern Seaboard and Jamaica, blessed with the most fertile soil of any island in the Caribbean, and where the banana grew in abundance. The first documented shipment came into Boston aboard the schooner Raymond in 1866, but the beginning of regular banana importation is credited to Capt. Lorenzo Baker whose schooner Telegraph landed the first large consignment at Jersey City, N.J. on 23 June 1870. By the 1880s, Boston became the great American banana port and the Boston Fruit Co. soon dominated the trade and much of Jamaica's banana production. The "banana boats" were quick converts to steam owing to the necessity of speed and regularity, painted white to keep the hulls cool and the holds primitively insulated and amply ventilated to remove the ethylene gas produced by ripening bananas.

|

| Harvesting bananas in Jamaica, 1890s. Credit:https://iamajamaican.net/ |

The island of Jamaica, formerly one of the most opulent of British possessions, has within the past quarter of a century fallen evil days,but better times may in store. No country in the world, not even Cuba, possesses a richer soil or finer climate, and her produce includes some of the most delicate fruits of the tropics. Jamaica has suffered from inadequate facilities communication with the United Kingdom, and it is nothing short of shameful that its fruits are practically excluded from British consumption. As showing what losers we are in this respect, may be mentioned that Jamaica sends yearly over 7,000,000 bunches of the finest bananas the world produces to the United States, whereas the total imports into this country from all quarters do not exceed 500,000 bunches per annum. And it is said that the fruit industry of Jamaica is yet in its infancy. Twenty years ago, its fruit exports totalled £39,451; ten years ago, £347,652; last year, £620.000.

Leeds Mercury 16 September 1899

Jamaica, oldest of the British West Indies colonies and rivalling Newfoundland and Bermuda as such in the Americas, was once the jewel of Britain's earliest mercantile Empire, built on sugar, rum and slave labour, and with Bristol the apex and object of the "Triangular Trade." When the Britain became one of the first countries to banish slavery and the Royal Navy swept the scourge of the slave trade from the world's oceans, Jamaica retreated into a sustained decline. The sugar plantations, denied their cheap labour and their product displaced from European market by the development of beetroot sugar, fell into disuse. At beginning of 19th century, Jamaica shipped over 150,000 tons of sugar and five million gallons of rum to Britain a year; by 1896 it had dropped to under 23,000 tons and two million gallons respectively.

|

| c. 1904 United Fruit Co. advertisement for Jamaica, promoted as a tourist attraction in America long before it was to Britons along with a virtual monopoly on its banana trade. |

The development of the banana trade was one of the economic glimmers of hope for the island, but as so much commercially and strategically, proximity mattered and at a time when the United States began to emerge as a nascent global power, much of Central America and the Caribbean had already fallen into its commercial orbit. In 1895, Jamaica exported 4 mn. bunches of bananas, 10 mn. coconuts, and 100 mn. oranges, almost all to the United States and 18 steamers left Jamaican ports a week for the U.S. Eastern seaboard. The old imperial credo of “trade follows flag” was turned on its head and like many of the “British” West Indies, Jamaica was drawn ever closer to America by distance, trade and its geographic location, being directly south of Cuba and some 1,600 miles distant from Barbados, the traditional gateway to the British West Indies from England. So distant from Britain, that Kingston was the last port of call on Royal Mail’s historic mail service route from Southampton, a voyage of some 16 days.

|

| Joseph Chamberlain: Domestic Progressive & International Imperialist. |

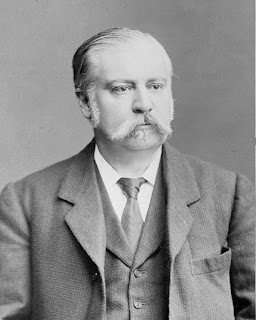

One of the most influential British politicians and statesmen of his day, Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914) was the typical great man of profound complexities, being at once a progressive reformer domestically and an ardent, even evangelical imperialist, who, as Colonial Secretary from 1895-1903, remade the British Empire for the first half of the 20th century or indeed its last epoch. He transitioned away from the ancient chartered companies to a federalist policy that envisaged The Empire as a great global Anglo-Saxon economic union and as a cure, literally, by materially assisting the creation of universities and foundations for the study and cure of tropical diseases. Chamberlain’s greatest passion as Colonial Secretary was the economic development of the hitherto neglected West Indian and African colonies to make them integral to a pan British Imperialist co-prosperity sphere. There were strategic objectives in play as well against rising American influence and presence in the Caribbean and German in East and Central Africa.

In December 1896, Chamberlain appointed a four-man West Indian Royal Commission to undertake a comprehensive appraisal of the local economies of the British Caribbean colonies. This included a four-month inspection tour and confirmed Chamberlain's fears that many, especially, Jamaica which was described as being "at a time practically bankrupt." Revival of the sugar plantations was an obvious solution but unworkable unless Britain could prevail on Europe removing protectionist tariffs to protect its own beetroot sugar industry.

|

| Illustration from the Gleaner showing Corporal G.S. Gale and Sir Daniel Morris on the Jamaica stand at the New Orleans Exposition. Credit Daily Gleaner 28 January 1891. |

Sir Daniel Morris (1844-1933), Imperial Commissioner of Agricultural in West Indies, promoted an alternative: expand on the existing banana production, break the monopoly held by Boston Fruit Co., and raise prices for independent planters, all by exporting bananas, instead of sugar, to Britain. Chamberlain seized on the idea immediately as being both commercial and strategically beneficial to Britain as well as appreciating that any service to transport the bananas would also facilitate improve mail communication as well foster tourist development in Jamaica which, like the banana trade, was almost wholly dominated by Americans. Indeed, the island was still regarded by many Britons as a pestilential hell-hole from the days of Port Royal and the buccaneers whilst Americans in increasingly numbers had already discovered its warm climate, cooling trade winds, incomparably lush countryside, scenic rivers, waterfalls and mountains.

The development of the banana trade and tourism were promising, but the distances were daunting. From Kingston to Boston is 1,712 miles and Las Palmas, Canary Islands (the existing source for most of Britain’s bananas at the time) to London is 1,800 miles-- combined they do not equal the distance between Kingston and Bristol: 4,576 miles or 4,000 nautical miles. Wider and wider still, Chamberlain's dream of The British Empire as a global free trade zone was constrained by the sheer scale of it not to mention the technology required to transport a delicate perishable like the banana 4,500 miles in edible condition.

Give the Pole the Produce of the Sun,

And knit th' unsocial climates into one.

Wedding bananas to empire was the comparatively new technology of mechanical refrigeration equipment to enable shipment, over extended distances, of frozen or chilled cargoes like meat and fruit. Indeed, nothing more revitalised Empire trade… especially from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the West Indies than the “reefer” ship. Yet, it was two Frenchmen, Ferdinand Carre and Charles Tellier, who first experimented with mechanical refrigeration in 1866. They installed an ammonia absorption freezing plant aboard City of Rio de Janeiro and then an ammonia compression plant aboard Frigorifique, with reasonable success. The first large successful shipment was made by Paraguay in 1878 which landed 5,500 frozen carcasses at Le Havre. Meanwhile, in 1879, the British employed cold air machinery aboard two ships, Circassia and Strathleven. In 1882, the sailing ship Dunedin in 1882 transported the first shipment of frozen meat from New Zealand to England. Orient line fitted their new Cuzco, Orient and Garonne with refrigerated hold space in 1881 as did P&O in 1887 and Shaw, Savill & Albion soon revolved around the frozen meat trade.

Bananas are not shipped frozen and required their own specialist handling in mechanically cooled chambers, the bunches loosely stacked in a constant controlled temperature of 56 to 59 degs. F. and with a constant flow of ventilation. Indeed, they were more challenging to transport by ship than frozen meat and it took a lot of experimentation and more than a few ripe and smelly failures to perfect the means and the method. Shipping bananas 4,500 miles from the tropics to Britain was technically possible by the close of the 19th century, now all that missing was the dynamic personality to bring the Jamaican banana to the British table.

He was a man of unique personality. It has been well said of him that, 'shrewd and successful as he was in business, and keen as he was in picking up a profit wherever he could find it, he was at the same time primarily and essentially Imperial in sentiment, and he never too closely counted the cost if he saw a worthy Imperial object to be attained, and thought he could attain it in the end.'

Bristol Times and Mirror, 6 January 1911.

So associated with the opening up of the whole of West Africa to steam navigation and British trade and influence in Nigeria, The Gold Coast, Gambia as well the Canary Islands, it may come as a surprise to learn that the West Indies, too, figured prominently if fleetingly, in the history of Elder Dempster and more enduringly in the story of the associated Elders Fyffes company. And whilst the name Elder Dempster endured, there was no Elder or Dempster associated with any of it past 1884 and it remains indelibly connected with the one man who made it a giant in the British Merchant Navy and a linchpin in Imperial Commerce in the late 19th century: Alfred L. Jones.

|

| Cover of 1898 sailing list for the African Steamship Co. & British & African Steam Navigation Co. |

In 1852 the African Steam Ship Co. began the first British mail ship service to West Africa with the aptly named Forerunner. A competing firm, the British & African Steam Navigation Co., began operations from the Clyde to West Africa in 1869. The names were confusingly similar enough to also guarantee some measure of amalgamation.The common element was Liverpool based Elder, Dempster & Co., founded in 1868 by Messrs. Alexander Elder and John Dempster, two gentlemen intimately acquainted with the working of the African Steamship trade. For 11 years they were the sole partners, but in 1879 they admitted Mr. (now Sir Alfred) Jones into the firm, and Mr. W. J. Davey was also taken into partnership. Elder, Dempster & Co. which assumed management of the "B&A" and then in 1891 of African S.S. Co. Curiously and confusingly, the two kept separate identities until the 1930s, the only outward differences being funnel (buff for "African" and black for "B&A") and houseflags. The original partners, Messrs. Elder and Dempster, retired from the firm in 1884. Mr. Alexander Sinclair, who became a partner in 1891, having retired in 1901, the sole partners at the beginning of the 20th century were Alfred L. Jones and W. J. Davey.

From the onset of the concept, there was one company, and more importantly, the man who ran it, who could realise Chamberlain's plans for importing Jamaican bananas to Britain. Not just a businessman or shipping executive but one of, if not the last and greatest "merchant adventurers" of the late Victorian Age: Alfred L. Jones (1845-1909).

|

| Sir Alfred Jones, Shipping Entrepreneur & Empire Builder. |

A PIONEER OF EMPIRE. In the crowd of claimants to the distinction both thinking and acting imperially. Sir Alfred Jones, K.C.M.G., may certainly have his place. The "Banana Knight," as the commanding partner in the banana fleet, the West Indian branch of the Elder, Dempster Steamship Line is pleasantly called, dreams ports and port seizure. He is a veritable Paul Jones in this respect. With a humane and commercially magnanimous eye, he is always the look-out for fresh ports of call. Sir Alfred is a Welshman birth, and was born at Carmarthen 1846. He gave examples of a vigorous future at a signally early age, and his capacity seize upon opportunities has been repeatedly illustrated to this country's good. It would be perhaps to belittle the race say that but for its virile chairman the sole office of the Elder Dempster fleet would have been to bring rubber and palm oil out of Africa, and carry back reanimated mummies, invalided home as the victims of merciless climate. But for reasons due largely to science and sanitation the Gold Coast, like the Red Sea, losing its ancient terrors, and to this science and this sanitation Sir Alfred Jones was quick to contribute. Sir Alfred founded the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine which has made war upon the mosquito by locating its poisonous energy to the swamps of the coast and the hinterland, and establishing the mosquito as agent to the distribution of fever.

Magazine of Commerce, 1908.

Born in Carmarthenshire, Wales, Jones had risen to manager of the African Steamship Co., Liverpool, by age 26 and later went on to head Elder, Dempster & Co. which acquired the African S.S. Co. in 1891. A man of limitless energy, drive and interests, remarkable even in an era filled with extraordinary business and shipping men, Jones was first and foremost an ardent exponent and champion of The British Empire whose views were entirely in harmony with Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain's in transforming the Empire away from the old Royal Charter Companies to a modern, dynamic free-trade global (but British) zone. Indeed, his zeal in developing trade in the region led Jones to be dubbed "The Uncrowned King of West Africa." Also to his credit was introducing the banana to the British table and creating the Canary Islands as a tourist destination.

An important waystop on Elder Dempster's principal route, from England to West Africa, were the Canary Islands, principally Las Palmas, for fresh water, provisions and coal. The later was shipped from Jones' owned collieries in Wales to Las Palmas for his Grand Canary Coaling Co., founded in 1886. Like any shipowner, full ships out and empty ones back was not an appealing prospect and Jones hit upon the idea of filling them with the ample crops of bananas that grew there in abundance. In 1888 Jones began to supply London food wholesaler Edward Fyffe (1853-1935) with bananas from the Canaries, entrusting the banana trade to 24-year-old A.H. Stockley. Fyffes merged with another food importer, Hudson Bros. to firm Fyffe Hudson & Co. Ltd. in 1897 by which time the banana became a staple of the British table and the company went on to buy land in the Canaries to establish their own banana plantations.

At the same time, Jones also sought to popularise the Canaries as a tourist destination, especially for health reasons, owing to its delightful year-round climate. There were few less healthy places than the conurbations of Victorian England and those suffering from bronchial diseases were legion and a ready market for the restorative sun and lung cleansing air of the Canaries which were also an easy few days steaming from England and could be accommodated readily on the through West African mailships. Victorians did not travel well and to cater to their habits and tastes, Jones created an veritable British colony in Las Palmas with the lavish Hotel Metropol, the first tennis courts and golf course in Spain, even the first swimming pool on the island.

|

| The first advertisement for tenders for four new West Indies steamship services, including "Service D" Jamica to Britain. Credit: Lloyd's List, 14 September 1898. |

On 14 September 1898, the Colonial Office advertised for tenders for services to Trinidad and St. Kitts (Service A), Trinidad, British Guiana, Barbados and Canada (Service B), St. Vincent, Dominica and US or Canada (Service C) and fortnightly or tri weekly fruit service between Jamaica and England (Service D). Tenders to be submitted no later 1 December

Service D. Fortnightly or Tri-weekly Fruit Service between Jamaica and England, under a subsidy or guarantee. A service of steamers, of not less than 1,500 tons net register, to run at a speed of not less than 15 knots, once in every three weeks or thereabouts, from a port or ports in Jamaica to a port in the United Kingdom. The service to be fitted for the carriage and cool storage of fruit. The service to begin not later than the autumn of the year 1899.

The object of this service is to develop trade, and especially fruit trade, between Jamaica and the United Kingdom.

The steamers employed in all or any of the above specified services are be British vessels, classed A1 at Lloyd's, and, except in the case of Service C, should contain first-class accommodation for a moderate number of passengers.

With a view of emulating what Jones had done in the Canaries, Chamberlain and the Colonial Office were looking for more just a means of carrying bananas 4,000 miles (something which in of itself had never been attempted and challenging enough on its own), but a complete distribution system on arrival in Britain and development of Jamaica as a tourist destination.

Typical of Jones' receptiveness to the general scheme and of his thoroughness, he dispatched A.H. Stockley, who was his expert in the banana trade, to Jamaica to investigate the prospects. He arrived on the island with a colleague in October 1898. This prompted their meeting with the Agricultural Society of Jamaica to "discuss the question of the establishment of a fruit trade with England, and in particular with Messrs. Stockleigh (sic) and Weathers sent out to investigate the position by the well-known London firm of Elder, Dempster & Co..."Mr. Stockleigh said their present visit to Jamaica was due to the fact that the Colonial Office has approached Mr. Jones, the senior partner of the firm of Messrs. Elder, Dempster & Coy., and asked him to take up the Jamaican fruit trade and run a line of steamers to the London market. The firm were approached in this manner because they had been very successful with the importation of bananas from the Canaries." (Daily Gleaner, 22 October 1898).

During his visit, Stockley learned that far from being an undeveloped resource, almost all of Jamaica's banana crop… totalling 6,945,590 bunches not to mention 85,612,164 oranges were shipped to the United States via the Boston Fruit Company. Yet, there was ample scope for more exports to Britain and Europe and whilst he stated that it was not the intention to compete with Boston Fruit Company, there was a desire among many of the planters to have an alternate market especially as the development of banana and fruit growing in now American held Cuba and Puerto Rico would possibly divert some American imports going forward.

Prospects for profits were not encouraging even for a start-up operation, Mr. Stockley telling the Daily Gleaner on 24 October 1898 that "if his firm undertook the service at all, they would do so fully prepared if necessary to drop a good round sum at the start. The loss of £20,000 or £30,000, for example, would not deter them." As for tonnage Elder Dempster had, at the time, no fewer than 15 steamers under construction, three of which could be adopted for the trade, on the stocks. With the anticipation that the service would commence about a year hence, there was not a lot of time to adopt the ships on the ways. There was also the matter of transporting the delicate banana in good condition 4,000 miles and initial trials had not been encouraging although important developments in refrigerating machinery were proceeding apace to ensure the bananas would reach England not too ripe to be distributed and in the shops. In the end, Stockley was not immediately disposed to the venture, and in fact, advised Jones not to pursue it. In addition, Elder Dempster had enough on their corporate plate at the time including the acquisition of Beaver Line, trading from Britain to Canada.

In commercial circles in Liverpool it is stated that Mr. Chamberlain has displayed great wisdom in trying to development trade with the West Indies. There is no doubt that if the present attempt succeeds it will do a great deal of good and not to British trade generally, but to the West Indies in particular, and a ray of hope will shine again upon a people who have, in several ways, been sorely afflicted.

Liverpool Daily Post, 3 December 1898

|

| The Daily Gleaner, 17 May 1899. |

It appears that only Royal Mail Steam Packet Co. submitted a bid by the 1 December 1898 deadline, for £40,000 per annum over five years, and was not prepared to undertake the banana distribution and tourist development aspects. Far in excess of what the Colonial office was prepared to pay, the bid was rejected on 29 April 1899. At the same time, there were rumours of the Americans slapping a 40 per cent duty on the import of Jamaican bananas to favour the producers in now American controlled Cuba and Puerto Rico which only heightened the Colonial Office's determination to provide an alternative British market.

|

| By September 1899, "The Direct Line" referred to the proposed service by the Jamaica Produce & Transportation Assoc. Credit: The Daily Gleaner, 9 September 1899. |

It seems incredible that such an unbusiness-like arrangement could ever have been made.

A.H. Stockley, Consciousness of Effort, The Romance of the Banana, 1937.

Not a man to be dissuaded, Chamberlain turned to an entirely new firm which suddenly sprang out of nowhere in summer 1899. On 1 July, in reply to a question put by the West India Committee of Parliament, the Colonial Office wrote: "a contract has now been signed [on 20 June] with the Jamaica Fruit and Produce Association for a direct fruit and passenger service between Jamaica and the United Kingdom, to commence in May 1900. The contract is for a period of five years, and the steamers will run fortnightly, at an average speed of 15 knots, between Kingston and Port Antonio and Southampton. The steamers will be fitted for the conveyance of fruit, and will have storage for at least 20,000 bunches of bananas. They will also possess accommodation for twenty-five first- class and twelve second-class passengers. The contractors bind themselves, inter alia, to employ at least six agents in Jamaica in developing the fruit industry, to improve the wharf accommodation at Kingston and other ports, and to build one or more hotels in the island. The subsidy payable is £10,000/. per annum, of which half will be contributed by the Imperial Government, to be increased to £12,000/. if more passenger accommodation is required."

This was announced in Parliament by Chamberlain on 7 July 1899. It was, by any standards, remarkable to engage a company that had yet to be even announced and with no experience in running a shipping line, let alone pioneering an altogether untried trade, with no capital and as yet, no ships. By the time the company was publicly listed the following month and registered in Edinburgh, it now called itself the Jamaica Produce and Transportation Association Ltd. "to carry on in Great Britain, Jamaica, and elsewhere the business of shipowners, shipbrokers, produce and fruit merchants, exporters." The syndicate was headed by Mr. Ronald Lamont, Managing Director, Robert Cousin, shipbroker of Glasgow and others in the shipbroking trade.

One of the founders of the association, Mr Ronald Lamont, who will act as managing director, has, “during his close identification with the West Indies, covering a period of fifteen years, had great experience in growing, transporting, and; disposing of fruit in the American markets,” and while the estimate of a profit margin of over 12½ per cent, per annum are conjectural, it is stated that an agreement has been entered into with the Crown Agents for the Colonies, under which a contract will fall to be entered into for the carrying of Majesty's mails, the purchase and transport; of fruit, and; for other purposes, under which the association; will receive a subsidy from the British Government equal to over 3 per cent. on the total share capital of the undertaking.

The Economist, 16 September 1899

On 18 September 1899 Jamaica Produce and Transportation went public with an initial stock offering of £300,000 with shares offered at £1.

In its Prospectus, the Company stated: "Contracts have been entered into with shipbuilders of repute in Scotland for the building of four steamers, in every way suitable for the trade and accordance with the Government requirements. These steamers are in under construction and will be ready to begin the service early in April, 1900. The net cost of the steamers and their equipment will be about £220,000." The Dundee Courier, 30 September 1899, reported that Caledon Shipbuilding and Engineering Co, Dundee, have received order for one of the four ships. The specifications were 290 ft. length, 41 ft. beam, accommodation for 28 First Class and 12 Second Class and triple expansion engines 31½ inches dia., 53 inches dia. and 85 inches dia. with a 48-inch stroke and 180 psi boilers.

Contracts have been entered into with shipbuilders of repute for the building of four steamers, in every way suitable for the trade and in accordance with the Government requirements. These steamers are now under construction and will be ready to begin the service early in April 1900..."considerable difficultly was experienced with Lloyds before the plans-- which are on a new style-- were accepted, but all difficulties have been removed. The vessels will have two compartments only, in order to admit of perfect ventilation with fans, etc. There will be cold storage in proportion to the requirements and capable of expansion.

Daily Gleaner, 5 October 1899

On 3 November 1899 the Daily Gleaner (Kingston) reported that "the builders have who received orders from the Jamaica Produce & Transport Association for four steamships are proceeding with their construction. Alexander Stephen & Sons, Linthouse, are to build two, Ramage & Ferguson, one, the Caledon Shipbuilding Co., Dundee, one."

By then, Jamaica Produce and Transport Association was already defunct. Upon his arrival in Kingston on 21 October 1899 aboard R.M.S. Orinoco, the Archbishop of Jamaica, the Rt. Rev. Charles Gordon, who was a curiously business-minded prelate and champion of Jamaica, related to the Daily Gleaner that only 70,000 shares had been sold by the Company which had failed utterly in its initial capitalisation and was entering into liquidation. Indeed, one of its principals, shipbroker Robert Cousins, appeared in Bankruptcy Court in June 1900 owing mainly to a loss of £5,616 incurred when he advanced the sum for the company's start up costs.

Mr. Chamberlain and the Colonial Office made strong efforts to arrange matters so that Elder, Dempster & Co. should undertake the contract. At the eleventh hour however, Elder, Dempster and Co. withdrew for business reasons arising out of transactions in Africa where they had an opportunity of securing immediate advantage to themselves. That advantage was sufficient to induce them to drop Jamaica for the time being. The Colonial Office had no alternative but to let this Co. [Jamaica Produce and Transport Co.] have the contract if they could raise the capital for they were the only tenderers left in at the last.

"It is my belief that the only way to realise our wishes now is by efforts from Jamaica. Elder Dempster & Co. are undoubtedly very successful people in this line. They have complete arrangements in England already for the disposal of the fruit, and they have every facility for making the trade between Jamaica and England a success. They must me approached by us in Jamaica in the proper spirit and then I am sure something could be accomplished. No body in Jamaica can realise how much the Colonial Office has done to make this direct line a success.

Archbishop Gordon, The Daily Gleaner, 21 October 1899

Indeed, it was Archbishop Gordon who galvinised interest in Jamaica to renew negotiations between Chamberlain and Jones. At Gordon's encouragement, a meeting of the Jamaica Agricultural Society was held on 17 November 1898, and endorsed the resumption of talks with Elder Dempster. The next day, the Daily Gleaner reported that "Stephens, of Glasgow, who have laid down two of the steamers, have not got the deposit up to last week. It was the consensus that Elder, Dempster & Co. were the only people who could handle the fruit of Jamaica to advantage."

In early December 1899 it was reported that Elder Dempster would take up the enterprise if a subsidy of £50,000-60,000 per annum was paid and that even with that sum, it was not expected to turn a profit for the company at the onset. After the Jamaica Produce debacle, Chamberlain and the Colonial Office were far more accommodating but still managed to prevail on Jones' innate patriotic imperial fervour to whittle down the subsidy to a still meaningful sum that could be accepted by all parties.

On 12 January 1900 Chamberlain cabled Jamaica advising that Elder Dempster had reopened negotiations: "Elder Dempster willing to contract for direct fruit service Jamaica for ten years, with steamers not less than 3,000 tons measurement, minimum speed 13 knots. Subsidy £40,000 on condition that if after three years larger steamers of 5,000 tons measurement are not employed, the subsity from date of beginning of service than be only £30,000, Date of commencement 1st January." Chamberlain proposed that the home government pay half the subsidy and Jamaica the other half.

The turning point in the more recent history of Jamaica has, at last, come, and it is not too much to assert that the colony has it in its power to determine what the course of its destiny is to be. Messrs. Elder Dempster & Coy, the great steamship owners, are now willing to come here and develop our fruit trade on certain conditions they have put forward; the Imperial Government is willing assist the arrangement, and it remains for the colony to decide whether it will accept the terms, and enter into the prosperity it will bring."

The Daily Gleaner, 15 January 1900

On 25 January 1900 the Colonial Secretary cabled the Jamaican Government that the Imperial Government had agreed to Elder Dempster's terms. On the 31st it was reported that the contract had been "confirmed" and that "arrangements for the starting of the service by next New Years Day are already making satisfactory progress." The Daily Gleaner, 31 January 1900.

A compact has been drawn up between the British Government, the Jamaica Government and Messrs. Elder Dempster, and & Co. which definitely received the signatures of the contracting parties yesterday, where by the latter parties agree to the undertaking guarantee that they will establish a quick steamship service between England and Jamaica, calling at two or three of the ports on the island, and a port in the United Kingdom, which probably will be one of three-- viz., Milford, Southampton or Bristol. The ships shall be specially designed to carry passengers and fruit, as it is intended to conduct an enormous trade in bananas, while oranges and other West Indian fruit products will also be carried for home consumption. The contractors will also established fruit depots, and undertake the thorough development of the fruit growing industry in Jamaica.

It is then to Messrs. Elder, Dempster, and Co. that the British Colonial Office, backed by the Jamaica Government, have turned for the relief of the old colony, and the dependence placed upon the firm and its ability to perform what has been under taken the business has been given into their hands.

Liverpool Journal of Commerce, 2 February 1900

The standing of the firm of Elder, Dempster & Co. in the fruit trade is well known, and it is doubtful whether any other organisation could so adequately control this business, which is practically only a development of the firm's enormous shipping trade. It would certainly seem that, by this comprehensive understanding between the parties to this agreement, Jamaica and the other West Indian islands are in a fair way to have their fruit placed upon the British markets on a businesslike scale and with some regard to that most important point in trading of this character-the regularity of the supplies. That the compact will be satisfactory to all parties and prove the beginning of a great development in the prosperity of the West Indian islands must be the sincere wish of all engaged in the fruit trade. It should not be overlooked that the unique prosperity of the Canary Islands fruit trade is to a large extent due to Messrs. Elder, Dempster & Co. Mr. Alfred L. Jones (the extremely energetic head of this firm) has our sincere congratulations.

Agricultural Journal of the Cape of Good Hope, 1900

So it was that with the dawn of a New Century, a new route, line, service and indeed a whole new trade came into being. Few were begun with more hopes, ambitions and expectations. In the spirit of the Age, it was the fulfillment of "making no small plans."

|

| Cover of passenger list, R.M.S. Port Kingston, 31 December 1904. Credit: Bristol City Archives. |

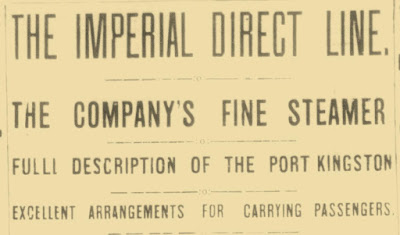

The inauguration of the Imperial Direct West India Mail Service is a matter of no small importance, not only to the inhabitants of the West Indies most nearly concerned, but to those of the empire in general. Started by the well-recognised energy and determination of Mr. A.L. Jones of Messrs. Elder Dempster and Co., with the hearty approval and assistance of the Colonial Secretary, Mr. Chamberlain, the line has opened under the happiest auspices, and the voyage of the pioneer vessel, the Port Morant, has excited the keenest enthusiasm amongst the inhabitants of Jamaica and Bristol, and no small interest elsewhere.

The British Medical Journal, 30 March 1901

Given one of the most imposing of names ever conferred to a steamship line, The Imperial Direct West India Mail Service, the route was always referred to, both in Jamaica and England, more prosaically as "The Direct Line." For it was truly just that, one of the longest nonstop point to point runs of any regular mailship service, stretching some 4,160 miles (3,614 nautical miles) from Bristol to Turk's Island where a brief stop was made to land mails and then onwards to Kingston, another 413 miles (358 nautical miles) for a total one-way distance of some 4,500 miles. The carriage of bananas demanded the directness, at least homewards, but also provided Jamaica with the most efficient and direct mail and passenger service with the Mother Country it would in fact ever enjoy. No longer at the end of the line of Royal Mail's extensive route from Britain, Kingston was now the nexus, the object of an entire steamship operation.

|

| A true Direct Line: via New York (12 days), direct from Bristol (13 days) and 16 days from Southampton via Royal Mail. Credit: Handbook for Jamaica. |

1900

The mail contract between the Colonial Office and Elder Dempster was signed in London at 3:00 p.m. on 19 April 1900, to take effect from 16 January 1901 and be in effect for ten years. Under its terms, the Company would maintain a sailing every 14 days maintained by steamers of no less than 3,000 tons, carrying forty first-class and fifteen second-class passengers and 20,000 bunches of bananas per trip. By 16 January 1904, the ships maintaining it would not be less than 5,000 tons, not less than 15 knots and carry 100 First Class 50 Second Class or the subsidy would be reduced by £30,000 per annum. Fares were set at First Class £25 single, £40 return, Second Class £20 single, £30 return. The British terminal was to be determined no more than three months before the commencement of service.

Collectively, the lines comprising Elder Dempster operated an extraordinary 150 vessels at the beginning of the 20th century, yet four more would required to fulfill its newest obligations in the West Indies. At the onset of negotiations, Jones had been keenly aware of the need for new, specially designed and built or, at least, adopted tonnage for what was an entirely new form of long distance maritime commerce, the shipping of a delicate, perishable and valuable cargo from the tropics to the British isles over a distance of some 4,500 miles, all on a rigid, defined and tight regular schedule also accommodating mails and passengers.

It was both blessing to already have two vessels under construction with the new service in mind but a curse, too, in that they had been designed by others with far less experience in the trade than Elder Dempster. If it was a complete failure, Jamaica Produce and Transport gave the new service its first tangible form. Before its collapse, the company had four sister ships contracted, of which two had been actually laid down: yard no. 387 at Alex. Stephen & Sons Ltd., Linthouse, and yard no.171 at Ramage & Ferguson's Victoria yards, Leith. The proposed third (by Caledon Shipbuilding, Dundee) and fourth (by Alex. Stephen) hulls were cancelled owing to lack of deposit and never begun.

|

| Certainly the most graceful pair of sisters ever owned by Elder Dempster, Port Morant (above) and Port Maria truly earned the adjective "yachtlike." |

As originally specified, these were to be only 290 ft. in length, 41 ft. in beam and accommodate 28 First and 12 Second Class passengers. In view of their graceful yachtlike lines, they were almost certainly designed by Ramage & Ferguson which specialised in steam yachts of which these were slightly enlarged versions. The model was not dissimilar to many of the early fruit ships, built for speed and of finer form and higher horsepower than conventional cargo vessels. As it was, the Alex. Stephens-built one was the first of no fewer than 26 "banana boats" built by the yard.

As originally designed, these ships were too small both from a passenger accommodation perspective and especially for the one essential capability which Jones and Stockley adopted for the new service: the compressed CO2 cooling system. In 1886 the Dartford workshop of J&E Hall (founded by John Hall) which hitherto made steam engines and gun carriages, invented the first practical mechanical cold air machine which would revolutionise shipping of perishables over long distances. This was followed the invention of the CO2 compression refrigeration by German Franz Windhausen the same year which was adopted by J&E Hall which specialised in developing and fitting refrigerated cargo space on ships. This proved ideal for the carriage of the bananas on the long voyage.

This system had recent been fitted and proved in the giant White Star liners Afric, Medic and Persic on the Australia-U.K. meat trade. So to accommodate the machinery for this as well as more accommodation, both hulls, already framed, were lengthened on the stocks by 30 ft., an operation quite novel at the time. The hulls were cut in two, after being partially plated, the after end launched down thirty feet, and the gap built in amidships. As much of the material for the second Stephens-built ship had already been ordered and delivered, this was used for the additional section. Adopting a naming convention of honouring Jaimaican ports, of which there were an abundance, the Alex. Stephens-built ship, Port Morant, was 329.6 ft. after lengthening and the Leith-built Port Maria, 334.7 ft.

Both were single-screw ships powered by triple-expansions engines, but again with slight variations, Port Morant's engines have cylinders of 30", 50" and 80" dia. and a 45" stroke whilst Port Maria was 31", 50" and 80" dia. with a 48" stroke. Both had four single-ended boilers working at 180 psi. Five refrigerated chambers had a 50,146 cu. ft. capacity while breakbulk cargo space totalled 1,420 cu. ft. Passenger accommodation was 45 First Class and 16 Second Class with a crew of 70.

|

| British Banana Boat: Port Royal and Port Antonio (above) set the pattern for the type for three decades. Credit: eBay auction photo |

For the second pair of ships, the first actually built and designed for the new Elder Dempster service, the company turned to one of its regular yards, Sir Raylton Dixon & Co, Middlesborough, which turned out handsome and well-found cargo steamers for Alfred Jones like sausages. Among them were Clarence, Elfreda and Mandingo, all launched in 1899 for the African S.S. Co. but completed the following year as Anversville, Stanleyville and Philippeville for Cie. Maritime Belge, then part of the Jones shipping empire. In 1906 they were transferred back to African S.S. Co. and reverted to their original names except Clarence which became Dakar, the trio henceforth known as the Dakar-class.

|

| The triple-expansion engines and a boiler of Port Royal and Port Antonio. Credit: The Engineer. |

With dimensions of 370 ft. (length), 46 ft. (beam) and accommodation for 100 First Class and 70 Second Class, the Dakar-class was the model for two dimensionally identical ships, Port Royal (yard no. 476) and Port Antonio (yard no. 477) for the Jamaican run. They differed in having their cargo spaces (132,534 cu. ft.) redesigned and reconfigured as cooling chambers, again using the Hall system, rearranged accommodation (120 First and 50 Second Class) and higher-powered machinery giving 15 knots instead of 12. The twin triple expansion engines, developing 5,415 ihp with cylinders of 24", 38" and 64" dia. and a 45" stroke drove two three-bladed screws. Four boilers working at 180 psi under Howden forced draught provided steam at 180 psi. Although their tonnage of 4,455 (gross) was slightly inferior, they anticipated the enhanced 1904 specifications of the contract. Even if adopted from an existing hull design and with the same machinery, Port Royal and Port Antonio set the basic pattern for British "banana boats" for the next three decades. Laid down in early winter 1900, it was intended Port Royal would inaugurate the new service the following January.

|

| A cutaway showing the arrangement of the cold chambers chambers and Hall CO2 machinery (just aft of the main engines) of Port Royal and Port Antonio. Credit: The Steamship 1 June 1901. |

Losing no time to begin promoting the new service to tourists for the forthcoming winter season, on 7 July 1900 Elder Dempster began an advertising campaign in the form a series of informative articles by Mr. Thomas Rhodes in the major London papers which would appear later in a new booklet on Jamaica. As with Jones' successful development of the Canaries, much of the promotion of "Jamaica, The New Riviera," was centred on health and rejuvenation, both by a sojourn in the warm climate of the verdant island with its Blue Mountain, rivers and waterfalls, sunshine and beaches and the tonic effect of the sea voyage itself from the damp fogs of Britain to the languid, blue seas of the Caribbean.

The announcement made Saturday by Mr A. L. Jones (of Messrs Elder Dempster and Co.) that his firm have decided make Bristol the port for the West Indian mail service, is the most encouraging item of intelligence received connection with dock matters for some time. It would be absurd to suppose that a business house having a contract to fulfill with the Colonial Office would select any particular port merely as a matter of sentiment, and we may take it that Messrs Elder, Dempster, and Co. were influenced by the fact that Bristol was once regarded as the natural home of the West Indian trade, and the further fact that the port is admirable centre for the distribution of the particular products which the West Indies supply.

Western Daily Press, 23 July 1900

|

| Hands Across the Sea: the twining of Bristol and Jamaica formed a major part of Imperial Direct's graphic image as did its purpose. |

A major announcement by Alfred Jones, on 21 July 1900, selected Bristol, specifically the rapidly developing port of Avonmouth, as the British terminus for the new service on account of its enviable geographic position to the major cities, produce distribution markets and direct rail links to them both for the carriage of bananas and fruit and passengers, London Paddington to shipside being possible in two and half hours by GWR special boat trains. Moreover, Bristol, had long been connected with the West Indies trade from the dark days of the Triangular Trade, would now be integral to a new and promising era of legitimate and mutually beneficial commerce that would establish it as Britain's prime fruit handling port for generations.

Whilst the operator of the enterprise always was Elder Dempster, the new service had its own name, if not houseflag or funnel colours, which duplicated those of the African S.S. Co. and soon its own corporate identity. On 6 September 1900, Fairplay reported that "a new company to be called the Imperial Direct West India Service is shortly to be floated with a capital of half a million to take over the ten years contract for the fruit and mail service to Jamaica at a subsidy of £40,000 per year, also the vessels are at present being built to fulfill the service. Mr. Alfred L. Jones of Messrs. Elder Dempster & Coy., will, I understand, be the chairman of the company."

|

| Western Daily News, 29 September 1900 |

On 29 September 1900 the first advertisements for the new service appeared listing the first voyage from Avonmouth by Port Royal on 16 January 1901 followed by Port Antonio, Port Maria and Port Morant. The Daily Gleaner of 18 October reported: "we understand that Messrs. Elder, Dempster and Co. have not relinquished the idea of trying to induce the colonial secretary and Mrs. Chamberlain to participate in the Port Royal's first voyage."

The first of the new Direct Line steamers to be sent down the ways was Port Royal at Middlesborough on 8 November 1900 by Lady Dixon before a large number of spectators including Mr. Alfred Jones. She was followed by Port Morant, on the 21st, at Alexander Stephens, Linthouse, yards, named by Mrs. A.H. Stockley.

Hopes to have the service inaugurated in January by Port Royal, were foiled by a strike at Dixons delaying her completion by six weeks and on 26 November 1900 it was announced that her maiden voyage would be put back to 6 February 1901.

|

| New Year 1901 Greetings from The Imperial Direct West Indian Mail Service. |

A.L. Jones telegraphed a Christmas message to the people of Jamaica via the editors of the Daily Gleaner:

Please convey to the people of Jamaica best wishes for a happy Christmas and for the future prosperity of the island. -- Jones

To which the Gleaner editor replied

The people of Jamaica, we are sure, heartily reciprocate the kind wishes of the future 'Banana King," and on their behalf we express the hope that the Imperial Direct West India Mail Service will be a magnificent success.

Daily Gleaner, 22 December 1900

Before the year was out, the third steamer, Port Maria, was sent down the ways by Miss Beilby at the Leith yards of Messrs. Ramage and Ferguson, on Christmas Eve 1900.

|

| The lovely Port Morant on trials on 6 February 1901 making 17 knots. Credit: McRoberts (Gourock) photograph. |

1901

On 14 January 1901 it was reported by the Times’ correspondent in Kingston that Port Morant would make the first sailing on 16 February, arriving Kingston on 1 March with the first homeward voyage beginning on the 6th. It was also stated "It has been found impracticable to carry out the provision to call at second port in the island, and this provision has therefore been waived by mutual consent. Messrs. Elder, Dempster, and Co., however, promise to put on, as early as possible, another service of steamers sailing to and from that port, Montego Bay, on the north side of the island and the terminus there of the main branch of the railway, is the port that has been selected. It has no harbour, but a large pier is to be built for the berthing of the steamers. The company is also establishing a local coastal service, which will be undertaken by the Delta, lately engaged in the West African trade."

|

| First advertisement for the new service and maiden sailing of Port Morant 16 February 1901. Credit: Lloyd's List, 18 January 1901. |

|

| Sailing notice for the first departures from Avonmouth. Credit: Western Daily Press, 1 February 1901. |

Favoured by beautiful weather, Port Morant ran her trials in the Firth of Clyde on 6 February 1901, "the vessel sustained a speed of 17 knots, which the builders and owners considered very satisfactory." A celebratory luncheon was served aboard presided over by Mr. Alexander Stephen. Setting off immediately on her delivery voyage, she reached Avonmouth on the evening of the 7th, carrying 300 tons of outbound cargo already loaded to which she took on about 600 more for Jamaica. "During last week she was visited by hundreds of persons, and her smart, yacht-like appearance and the excellent arrangements made for passengers were generally admired." (Western Daily Press, 18 February 1901).

|

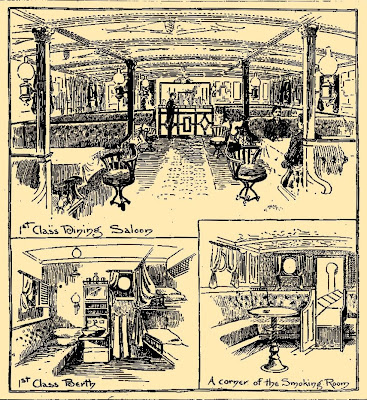

| Port Morant's First Class interiors. Credit: Daily Gleaner, 2 March 1901. |

The passenger accommodation has been specially arranged, so as to keep the berths as cool as possible in the West Indian climate. The dining saloon is abaft the bridge deck, and the walls are tastefully lined with birch and carved oak panels. The berths are arranged on either side of a large passage, at the fore end of which there is a door which may be opened when a through draught is required. The boats are carried "outboard," and owing to this arrangement a clear promenade is provided on the bridge deck. The accommodation for the second class passengers is abaft the first-class and on the port side of the bridge.

Western Daily Press, 7 February 1901

On the eve of the maiden voyage, Alfred L. Jones hosted a banquet at Bristol's Royal Hotel attended by most of the city's civic and business leaders as well as company officials and Capt. Parsons of Port Morant.

|

| Credit: The Sphere, 2 March 1901 |

Interest in Saturday's event was exhibited Bristol the display of bunting the vessels the harbour, but it was at Avonmouth, of course, the principal manifestations of enthusiasm occurred. Flags were freely exhibited not only in the dock enclosure, but throughout the rapidly growing town. The Port Morant, with a line of banners stretching from mast to mast, was especially gay, and the flagstaff beside the lock carried a mass of bunting, with the Bristol flag waving proudly from its summit. Since coaling, the Port Morant had been re-painted and her decks thoroughly cleaned, and she looked exceedingly trim and neat as she lay in the dock ready to start her maiden voyage to Kingston. A pennant flying from the foremast bore the words " Royal Mail," while the house flag of Messrs Elder, Dempster, and Co. was displayed on the aftermast."

… and punctually at four o'clock she cast off and started on her 13 days' voyage. Cheers were given by the crowd, cannon were fired, and the Avonmouth band, stationed on the pontoon, played "The Girl I Left Behind Me." The service was thus inaugurated under the most promising auspices, and the send off was an enthusiastic one. The weather was fine, and the sun was shining in the western sky as the Port Morant steamed down the channel, followed by the good wishes of the Bristol citizens for the success of the enterprise in which she had been selected to take a leading part.

Western Daily Press, 18 February 1901

|

| Sadly not a colour print, but a splendid portrait by Charles Dixon of Port Morant's maiden voyage from Avonmouth. Credit: The Graphic, 23 February 1901. |

Mr. A.L. Jones held a luncheon party on board the s.s. Port Morant to-day just before the new steamship sailed for Jamaica. Great crowds assembled to witness her departure, bunting was displayed everywhere, and music was provided by the Post Office band. Everyone was extremely pleased with the board. She left Avonmouth with a full number of passengers at 2.45 p.m.

Bristol, 16 February 1901

Daily Gleaner, 18 February 1901

|

| A banner day for Bristol as R.M.S. Port Morant sails from Avonmouth on her maiden voyage. Credit: Bristol City Archives. |

With 45 passengers aboard, 36 and 600 tons of general cargo aboard, R.M.S. Port Morant (Capt. J.G. Parson) sailed from Avonmouth on 16 February 1901 amid scenes of celebration and a crowd of some 8,000-10,000 not afforded a vessel's leaving from Bristol since Great Western departed on her epoch making first trip to New York. Port Morant had a rather rough passage to Kingston where she arrived on 1 March after a passage of 12 days 14 days 10 mins, to more general acclaim. Her return trip, commencing on the 6th was all the more important, marking as it did the first shipment of bananas from the West Indies to Britain. In all she sailed with more than 20,000 bunches and 14,000 cartons of pineapples and oranges in her cold chambers, all of which arrived in good condition on the 19th.

|

| The first arrival of Jamaican bananas and fruit in Britain aboard Port Morant at Avonmouth on 19 March 1901. Credit: Illustrated London News, 30 March 1901. |

The arrival of the Port Morant at Avonmouth on March 20th was therefore of some important. The good ship was greeted on her arrival by many interested in her welfare, and in the successful development which she initiates of the new branch of trade by this country with a colonial product. Her cargo consisted of large quantities of bananas, oranges, grape fruit, mangoes, etc., which had been on board for fourteen days. The unloading commence in rather unpropitious weather. The hatches were protected from the rain, and the men handled the fruit with care. The railway fruit waggons were drawn up alongside the ship, and a large number of men were busily engaged in the handing up of the fruit from the holds to other one who passed it along to the waggons. This work began at 8.30 in the morning, and to 10 o'clock the first special train load of 1,000 bunches of bananas was on its way to London. Other special trains left soon afterwards for Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and elsewhere. Mr. A. Stockley, Messrs. Elder, Dempster & Co.'s manager, who has organised the new service, travelled on the Port Morant, and expressed his entire satisfaction with the results of the trip.

The King, 30 March 1901

|

| First British Banana Boat at Bristol: left, bananas stacked in one of Port Morant's cold chambers and being off-loaded at Avonmouth. Credit: The King, 30 March 1901. |

The Port Morant carried a larger proportion of bananas fully ripe than will be shipped in future trips, but these involved no loss, for the market was only lightly stocked and they were in immediate demand. Five special fruit trains were despatched to various centres, two went to London, the first being due to arrive in time for the bananas to be put on the afternoon market. In addition, large numbers of fully-laden trucks were attached to goods trains throughout the day, and in every instance the bananas were, for the first time in the history of the trade, carried unpacked, only thin layers of straw being placed around the bunches, which were stacked on end in covered trucks. The most northern point to which large consignments were sent was Aberdeen. Liverpool merchants sent considerable quantities to Belfast and Dublin. The bananas showed no waste fruit, being sound, full, large, and ripening to a pure golden colour. The merchants admitted that the prices at which they were put on the market allowed of an appreciable reduction in existing rates. Although the fruit chiefly consisted of bananas, there were in the cargo pineapples, oranges, pomelos (or grape-fruit), and mangos. The pineapples were of two descriptions—the native growth, known as the Ripley, and the smooth cayenne, cultivated mainly in the Azores, but now being grown in Jamaica specially for the English market.

The Financial Half-year, Volume 1, 1901

As previously mentioned, the Direct Line established a feeder service from Jamaica's northern coast (Montego Bay, Port Antonio, Savanna la Mer, etc.) to carry bananas, fruit and other cargo to Kingston for transshipment to the Avonmouth steamers. This was held down by the 585-grt, 196 ft. x 28 ft. Delta, launched at Swan Hunter on 28 April 1900. The single-screw, compound-engined vessel (9 knots) had originally been built for British & African S.N. Co. for similar service on the Nigerian coast and designed to cross the bar at Lagos. Transferred to Direct Line, Delta left Lagos on 15 January 1901 commanded by Capt. Neale and reached Kingston 29 days later. She was drydocked at the Atlas slip dock, painted white, and made her first voyage to the north coast on the 19th, becoming the second Direct Line steamer to enter service. The ship could also accommodate four passengers in addition to 39,420 cu. ft. of cargo.

|

| R.M.S. Port Royal, the first of two much larger Direct Line steamers built by Sir Raylton Dixon & Co. at Middlesbrough. Credit: Bristol City Archives. |

The second voyage of the mail service was made by the first of the "bigger boats," the 4,455-grt Port Royal, from Avonmouth on 2 March 1901, commanded by Capt. James A. Murray. She, alas, had a very stormy first trip and did not reach Kingston until the 15th after 13-day 4-hour passage. "Everywhere excellent design and workmanship are shown, and the ship has a rakish appearance on the water. The upper deck is of teak wood and will form an excellent floor for dancing on the way out or home. This deck is 160 feet long, and over it on both sides a double awning will be stretched to shade the passengers when the weather is hot." (Daily Gleaner, 16 March 1901). Port Royal's first consignment... 19,635 bunches of bananas and 2,050 cartons of oranges... well filled her cold chambers upon departure for Avonmouth on the 21st.

"Working smoothly and steadily, the steamer fulfilled all expectations, and satisfied speed requirements by steaming at a speed of 15 knots per hours.." (The Steamship), after trials on which she averaged an impressive 16.5 knots, Port Maria left the Firth of Forth on 9 March 1901 for Avonmouth. She was described as being "one of the largest and most strongly engined vessels built on the Forth." Her maiden departure from Avonmouth on the 16th was additionally notable for being the first ship to use to the new passenger station at the dock . The ship came alongside after loading cargo at 2:00 p.m. and the special train left Bristol Temple Meads at 1:05 p.m. and came right alongside. "Storm-beaten and belated," is how the Daily Gleaner described Port Maria (Capt. H.F. Bartlett) as she arrived at Kingston for the first time on 30 March 1901, more than a day late after encountering "bad weather from the commencement of the voyage" from Avonmouth on the 16th. From the 19th to the 22nd the northerly gales and high seas were bad enough to reduce speed to 10 knots. Even so, deck fittings were damaged by the seas. She reached Turk's Island on the 29th and put in a fast run to Kingston. She sailed for Avonmouth on 4 April.

|

| R.M.S. Port Antonio sails from Avonmouth on her maiden voyage 20 July 1901. Credit: Bristol City Archives. |

Finally completing the quartet, Port Antonio was launched on 22 March 1901 by Mrs. Harald Raylton Dixon and "not expected to be placed on active service until the end of May." (Western Daily Press). As it was completion of Port Antonio lagged and trials were finally run 11-12 July, during which she averaged a speed of 15 knots, and then she proceeded to Avonmouth. Aboard for the trials and delivery voyage were Alfred Jones and a party of invited guests and the trip was enjoyed in fine summer weather. "The trip round the coast in view of the well-known heads, capes, points, lights, islands, rocks, and the all too unknown scenic beauties of the south coast of the British Channel, was really delightful. On Mr. A.L. Jones leaving the ship at Avonmouth the whole of the crew mounted the forecastle head and gave expression of their esteem for him by singing 'He's a Jolly Good Fellow.' (Daily Gleaner, 3 August 1901).

Externally the Port Antonio presents an imposing as well as a pleasing appearance, owing to the great length of her central deck-house, which is painted white, and rising above her white hull produces the effect of a vessel of much great dimensions.

On the promenade deck this deck-house contains forward, the chart room and the captain's quarters-- surmounted by a navigating bridge over that, for docking purposes-- the ladies room and the entrance to the main companion way: and aft, the first class smoke-room, a particularly spacious and comfortable apartment. On the deck it contains the saloon-- a beautiful room with marble walls and mahogany fitting-- and a large number fine staterooms. The other first-class state rooms-- baths etc-- are on the main deck. The second-class passenger accommodation is also on the main deck, just at of the first-class accommodation on that deck. The saloon is in polished teak, with white panelling above the wainscotting, and a white pannelled ceiling with a lanthorn light in the centre. The cabins are only less sumptuous than those of the first-class, and are equally well ventilate. The smoking room is on the upper deck and opens on to the deck space reserved for second-class passengers.

Western Daily Press, 16 July 1901

The fourth maiden voyage for Direct Line, that of R.M.S. Port Antonio (Capt. James Murray), commenced from Avonmouth on 20 July 1901. High summer not being a high season for the West Indies saw her sail with but 17 passengers aboard, but according to the Western Daily Press: "The departure of the ship awakened interest and enthusiasm at Avonmouth. The school children, numbering two or three hundred, were assembled near the pier, where they sang and cheered when the vessel left, and a selection of music was performed by the Avonmouth band."

"Picturesquely and lavishly decorated with flags and buntings" Port Antonio "gracefully steamed" into Kingston on 2 August 1901. Unlike her fleetmates on their maiden voyages, she experienced splendid weather throughout. Her maiden northbound voyage commenced on the 8th, taking away 24 passengers and full cargo: 26,472 bunches of bananas, 320 puncheons of rum, 50 tons of logwood, 107 cartons of oranges, 600 bags of pimento, 50 bags of coconuts and 145 bags of coffee.

|

| In 1901, Elder Dempster published the first general tourist guide for Jamaica for the British market, written by Thomas Rhodes. |

The New Riviera. Messrs. Elder, Dempster, and Co. have adopted the above heading in advertising their Jamaica hotels and the Imperial Direct West India Mail Service, which the firm established at the beginning of last year. This title for Jamaica is likely to attract attention from those in the habit of visiting the Riviera, and a change of programme for the winter and early spring months would be found beneficial to frequenters of “the sunny South.” Too much is not claimed by any means in the classification, by name, of the beauties and health-giving properties of Jamaica, for that land of bright sunshine in the Caribbean Sea provides the most marvellous and beautiful scenery, and every shade of climate that man can desire. In lieu of the pretty villas of Italy which dot and relieve the landscape, the picturesque homes of the planters beautify the scenery of Jamaica. The new portion of the Constant Spring Hotel is to be opened December 1 with a garden party and other entertainment.

Journal of Horticulture, 25 October 1902

Bananas were in abundance but the passenger traffic took time and effort to develop and whilst more speculative than the one-way banana and fruit trade, the passenger and mail aspects of the service were integral to its prospective profitability. It was a hard sell, not only was Jamaica hardly known to British tourists (as it was already among many Americans), but it remained a 13-day voyage out and 13 days back, uniquely with no waystops en route. Thus, it remained essential to promote the pleasurable and restorative aspect of the crossing itself, which certainly in winter, promised warmer and sunnier weather with each passing day at sea.

|

| Credit: The Handbook for Jamaica, 1901 |

In early 1901 Elder Dempster had published one of the first booklets/guides to Jamaica for the British market, Jamaica and the Imperial Direct West India Mail Service, compiled from a series of articles by Thomas Rhodes. This included a fulsome and enticing description of the voyage which began:

...the course steered misses the Bay. It is a south-westerly line some 4,000 in extent, just to the westward of the Azores, where soft fragrant breezes and a lazy blue sea gently fan and rock the travellers out of all recollection of ills mental or physical. Sportive dolphins circling round the ship with easy movement, a drifting nautilus, a cloud of flying fish skimming the surface of the water, an occasional whale in the distance, and now and again a passing ship, constitute the sights he is likely to see. With a serene mind and an awful appetite he will not ask more. There are many worse ways of enjoying like than that of reclining in a deck chair of a good ship.

|

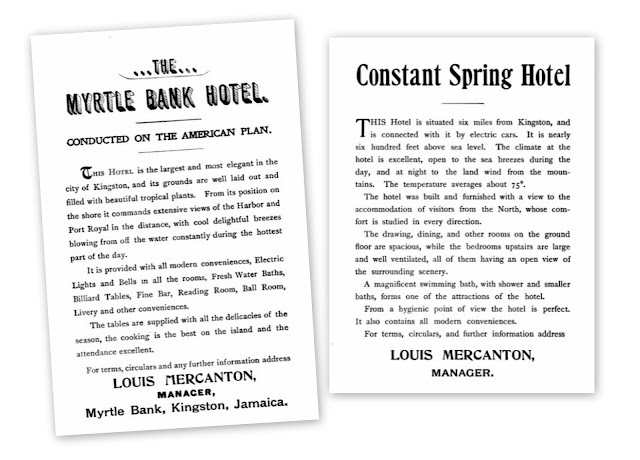

| The Elder Dempster managed hotels in Kingston, Mrytle Bank (left) and Constant Spring (right). |

To those for whom the sea has no terrors the trip out and home in the same vessel, with a stay of five days in Jamaica, can be warmly recommended both as source of pleasure and as a means of regaining health.

British Medical Journal, 30 March 1901

With the onset of the winter season 1901-02, promotion and publicity of Jamaica, "The New Riviera," and with emphasis on it as a health resort, went into full gear. Indeed, British medical journals soon featured regular articles extolling the "tonic" effects of the sea voyage combined with a week or more at one of the two Elder Dempster-managed hotels in Kingston: the Myrtle Bank and Constant Spring.

|

| Credit: The Spectator, 1902 |

The Myrtle Bank, Harbour Street, dated from 1891 to accommodate visitors for that year's World's Fair, and the Constant Spring, built in 1887, occupied a lovely situation 600 ft. above sea level and six miles from Kingston, at the terminus of Kingston's new electric tramway, and famous for its golf course, tennis and spacious grounds, were owned by the Jamaican Government but leased and managed by Elder Dempster which also spent £30,000 in improvements in them and another £20,000 in promotion in the British market. Emulating Elders Dempster's scheme in the Canaries, Direct Line offered inclusive packages at either at full board in combination with roundtrip passage from England. In December 1902, the extensions to the Constant Spring Hotel were opened as was the new golf course, "His Excellency Sir Augustus Hemming, K.C.M.G., drove the first ball on the hotel's golf links, and subsequently made an interesting speech, in which he paid a tribute to the efforts of Sir A. Jones and Messrs. Elder, Dempster and Co. to resuscitate Jamaica's prosperity. (Golf Illustrated, 12 December 1902).

It should be noted that United Fruit Co. owned and operated their own hotel, The Titchfield in Port Antonio, also in connection with its steamers from U.S. ports so Anglo-American competition existed for both tourists and bananas.

|

| Direct Line postcard for Port Antonio also featuring the Myrtle Bank Hotel. |

Elder Dempster's contract was unique in shipping since it not only obligated it to carry the bananas… 40,000 bunches a month… but in effect, purchase them from the growers and distribute them for retail sale on arrival. A 23 January 1901 contract between Elder Dempster & Co. and Messrs. Fyffes, Hudson & Co. (on behalf of an intended company called Elders & Fyffes) set a rate of £2,000 but not exceeding £2,500 for the carriage of 20,000 bunches of bananas from Jamaica to Avonmouth by Imperial Direct every fortnight for 10 years from 6 March 1901. Tasked with effecting the rationalisation of the banana side of the business, A.H. Stockley appreciated that it was beyond the capabilities of Elder Dempster on their own and began negotiations with Fyffe, Hudson & Co. to join forces with a new joint company that would task E-D with the shipping aspects and Fyffe, Hudson & Co. with the growing and cultivation on one side and the distribution and sales on the other.

It was a typical Alfred Jones venture and with his Imperial Direct Line hardly turning a profit, he still bought half the shares of the newly capitalised (£150,000 in £1 shares) Elders & Fyffes which was set up on 11 May 1901 with William Davey owning most of the remaining shares. Arthur Stockley was Managing Director and the former managers of Fyffes & Hudson, too, were directors of the new firm. Further establishing Avonmouth as Britain's "Banana Port," C.J. King, the tug company of the port, had a small holding in the new company. It should be stressed that Elders & Fyffes were in no way contractually obligated under the Elder Dempster contract with the Colonial Office, and indeed came to operate a parallel but entirely complimentary service with its own ships that turned the Direct Line's fortnightly service into a weekly one, at least as far as the carriage of bananas was concerned. On 9 May a contract between Elder Dempster and Elders & Fyffes was signed for 10 years to deliver not less than 20,000 bunches of bananas every fortnight.

More corporate housekeeping was effected with on 9 December 1901, the Imperial Direct West India Mail Service Co. Ltd. was founded with £500,000 capital with 50,000 shares @ £10 pounds, with Alfred Jones, Chairman, and W.J. Davey, Secretary. On the 31st Elder Dempster sold Port Royal, Port Antonio, Port Maria, Port Morant, Montrose, Garth Castle and Delta valued at £475,000 plus 25,000 in goodwill to the new company, Jones received £250,000 and 25,000 in shares. In the event, Montrose and Garth Castle never operated for the Direct Line. In its prospectus published on 15 January 1902, "I.D.W.I.M." stated that "the company has been formed with the primary object of developing trade between the West Indies and Great Britain. Sixteen (16) complete voyages have been performed, and voyage accounts closed up to the 12th December last, with undoubted success, and now that the initial difficulties incidental to the inauguration of a new trade have been successfully overcome, much greater developments may be confidently expected." It was certified that the company made a £37,572 profit to date.

1902

It is to arrest the irresistible drift of trade towards the United States that Sir Alfred Jones, in conjunction with Mr Chamberlain, has stepped in; and, looked at from this standpoint, his enterprise in connection with the fruit-carrying trade to the United Kingdom assumes the level of imperial importance. The Imperial Direct Line is a true link of empire.

Chamber's Journal, March 1902

In Feb., 1902, Sir Alfred Jones, K.C.M.G., the chief of the Elder Dempster steamship line, set out from Avonmouth in the "Port Antonio" for Jamaica, with the object of promoting further developments between Bristol and the West Indies by means of the Imperial Direct West India mail service. The occasion of his departure was unusually interesting, as it took place on the first anniversary of the sailing of the first boat of the direct service carrying His Majesty's mails to the Island of Jamaica from Avonmouth. The picture portrays the mails being embarked on the "Antonio's" sister ship, the "Port Royal," which arrived at Avonmouth on the day before the royal visit, and was inspected by Their Royal Highnesses, who were much interested in her banana cargo.

The King's Post

Making his first trip to Jamaica, the now Sir Alfred Jones, embarked on Port Antonio on 15 February 1902 and was treated to an exceptionally "tempestuous voyage" with strong headwinds and gales for the first 9-10 days of the crossing and celebrated his birthday celebrated aboard on the 24th. When interviewed by the Gleaner on arrival on 2 March, he said: "I am more than satisfied with the success which the line has achieved so far. The tourist traffic is going to be a big thing, thanks very largely to the yeoman service dome by the Press, both in the mother country and in Jamaica, in making known the beauty and charm of the colony. We have not made a success all along the line with the fruit, as you know, but we could hardly expect that. We have not made a profit on the fruit, but we have gained a great deal of experience, and expect to do better and better as time goes on." He also said plans included extending the wharf at Kingston and to "build a fine new steamer capable of carrying 300 passengers." This was the first mention of what be Port Kingston. He returned to Avonmouth on 11 April aboard Port Antonio.

It is understood, however, that the firm are contemplating further additions to their West Indian fleet. Sir Alfred L. Jones accompanied by Mr. R.B. Raith, construction superindendent for Messrs. Elder, Dempster & Co,, and Mr. Harold Dixon, director of the Imperial West India Mail Service, recently visited the West Indies with the object of finding out definitely the requirements and possibilities of the trade. The result is a policy of expansion, if not quite, as and very much faster than the new steamers which have already developed the West Indian fruit and passenger traffic to a remarkable extent will require to be built. It is the policy of Sir Alfred L. Jones to be always building new vessels, and now that his present list of orders is practically completed, the Imperial Direct West Indian Mail Service, in which the Secretary for the Colonies has taken such an interest, is almost certain to secure the first installment of the firm's new work.

Glasgow Herald, 28 April 1902

Ironically, 1902 would see two quite parallel courses of action by Jones and Elder Dempster regarding their West Indies enterprises that would eventually collide with one another: a dramatic expansion of the Direct Line fleet and a diversification of their fruit business.

Jones' passing comment aboard Port Antonio on arrival at Kingston regarding the imminent plans for a "fine new steamer capable of 300 passengers" was no idle talk especially for man who, had in the space of two years, commissioned some 22 newbuildings. The one proposed for Imperial Direct was, not only far in excess in size and speed of her fleetmates, but would be far larger than any Elder Dempster liner. Moreover, it was early mooted she would be first of three such ships, going well beyond the contractual obligations to replace the smaller Port Morant and Port Maria by 1904. Both of these had proven to be poor seaboats, doubtless owing to be lengthened, and overpowered with consequent high fuel consumption, consuming 1,600 tons of coal roundtrip. The "well beyond" was summed up by C.R. Vernon Gibbs in British Passenger Liners of the Five Oceans: "The company was committed to placing larger ships on the route and Port Kingston of 1904 was really a bid for the main West Indies mail contract, held by Royal Mail S.P. Company and due for renewal."