It always seems to me that these two ships have been most unfairly belittled in references to them in the Press. That they rolled, that the services on which they operated were not a success, that the Cunard Line rid itself of Royal George as soon as possible, are frequently stressed. But the Royal George was designed and built by one of the finest yards in Britain for a fine weather express service. Within two years she was pitchforked on to a route just about as different as it well could be from that for which she was designed. As a trooper she did excellent work, and in her last years she was taking the place, temporarily, of ships over three times her size which had already established a worldwide reputation for themselves....The Royal George's sorry end, after only 15 years of strenuous life, was no fault of hers.

J.H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, October 1957

|

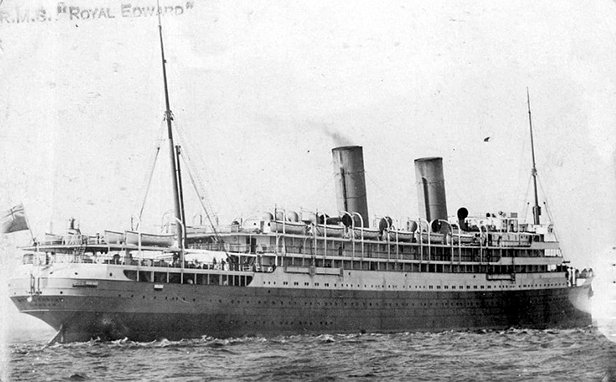

| Royal Edward Outward Bound from Avonmouth-- Farewell to Old England. Credit: delcampe.net |

Royal Edward and Royal George managed to earn a measure of success during their short four-year careers, cut short, like the Edwardian Era they so exemplified, by the Great War. They were uniquely Canadian in their new roles. Canadian-owned, they held the Blue Riband of the St. Lawrence Route route and were the first trans-Atlantic liners ever to be registered in the Dominion. On "the other side", they were also, just as uniquely, West Country ships, the only trans-Atlantic liners based on the historic port of Bristol.

Both performed valiant and valuable service as transports in the Great War. Royal Edward was tragically sunk with great loss of life in the Gallipoli Campaign whilst Royal George survived and "filled in" briefly on Cunard's express service afterwards. Doubtless among the most handsome pair of sister ships ever built, they surely earned more enduring success. And their story deserves to be told.

ROYAL ROUTE

A notable event in the history of steam navigation between England and Canada was the departure from Bristol last Thursday evening of the "Royal” liner Royal Edward. This vessel and her sister ship Royal George are the pioneers of the express service between Avonmouth and Quebec and Montreal which will be conducted by the Canadian Northern Steamships, Limited. This concern is, of course, part and parcel of the Canadian Northern Railway system, a vast undertaking which has been brought to its present powerful position by the energy, doggedness and foresight of Messrs. Mackenzie and Mann.

The Syren & Shipping, 18 May 1910

The twin-ship beginning of the Canadian Northern Royal Line of passenger boats is conclusive proof that the day of the Canadian route to the British Isles, not only for Canada but for the United States has arrived. With it has come also the recovery by Bristol of her place as the port from which the quickest passage to British North America are made; for the Royal Line connects Montreal with the West of England, and also with London, by the shortest sea route travelled by the fastest steamers; and by the shortest rail route-- the Great Western-- covered by the fastest trains that are in all-British service anywhere in the world.

The Atlantic Royals

Whilst the modern history of Canada as a unified nation dates from 1867 and the creation of the Dominion, she remained a vast country with a tiny population of just 3.7 millions concentrated in the eastern and maritime provinces. Her growth and unification came with the construction of the first trans-Continental railway (the Canadian Pacific), the opening up of vast expanses of western prairie to settlement and farming, mostly through immigration from the British Isles and northern Europe, in the 25 years before the Great War by which time the Dominion stretched from Atlantic to Pacific and eight millions called it home. All of which was accomplished by a remarkable combination of railway and steamship lines, indeed the first "intermodal" transportation system, pioneered by Canadian Pacific, which also with the introduction of trans-Pacific service, bound Canada into an "All Red Route" that circled the globe. By 1914, Canada was not only the bread basket of the British Empire, but an increasingly important link in the chain of Imperial commerce and communication.

Canada's first transcontinental railway assumed a role far more profound than even its vital transportation function: it helped to unify the new Dominion from coast to coast as its first great national enterprise. And there was sufficient purpose, grit and enterprise, encouraged by the Government of Premier Laurier, to create another one. William Mackenzie (1849-1923) and Donald Mann (1853-1934) were among the great Canadians of their age, archtypical Edwardians and self-described Canadian Imperialists, whose own early railroad careers stemmed from the first transcontinental line and motivated by the almost unlimited scope the great Canadian West offered for "Emigration and Colonization".

Sir William Mackenzie and Sir Donald Mann were among many Canadian entrepreneurs and contractors caught up in the flurry of railway construction in Western Canada after the completion of the CPR. Their initial focus was on Manitoba and also linking lines to the U.S. border. In January 1896 they acquired the bankrupt Lake Manitoba Railway & Company and three years later Mackenzie & Mann established the Canadian Northern Railway and began construction of lines from the Canadian Prairies to Port Arthur on Lake Superior and by 1902 had created a very profitable 1,200-mile network.

Urged on by Premier Laurier, CNR began expanding their network west beyond Edmonton and create "a second transcontinental" railway, an heroic engineering task and a huge financial risk especially duplicating lines on the eastern end as well having to use less desirable rights of way west around the existing CPR lines. The realisation of this epic Halifax-Vancouver line in 1915 was truly the last great achievement of the Edwardian Era yet already sublimated by the evolving horrors of the Great War and overtaken by crushing and unsustainable financial losses to achieve it.

From the onset, Mackenzie & Mann thought of the "second transcontinental" as part of a CPR-like intermodal transportation empire built on furthering immigration and settlement in the West. CNR would, like CPR, operate its own ships to carry the immigrants to Canada and onwards into the heart of the Prairies on CNR trains, literally from quay to farmstead and indeed sell them the farmland as well.

Although it was intended that the steamship operation would complement the railway, as events proved, it was the opposite and it was far easier and cheaper to buy existing ships and start a trans-Atlantic line than lay 3,000 miles of railway line across the second largest country in the world. Indeed, the establishment of the shipping line was accomplished in remarkably short order and, following Mackenzie & Mann's start in the railroad business, it was achieved through the misfortune of others.

In 1909, Mackenzie & Mann acquired the Northwest Transport Line, which dated only from the previous January, and renamed it the Uranium Steamship Co. after the single vessel owned by the line. This service, wholly emigrant oriented, ran from Rotterdam to Halifax.

The previous year, Fairfield Shipbuilding found themselves saddled with two almost brand new ships of their construction whose owners had gone bankrupt. Holding liens on them pending payment of their construction costs upon completion, Fairfield repossessed them and even briefly tried to operate the vessels themselves. The erstwhile prides of the defunct Egyptian Mail Steamship Co., the 11,100-grt, 20-knot triple-screw turbine steamers Heliopolis and Cairo, were among the finest and fastest liners of their age. Yet, in the wake of the 1907-08 depression and resulting collapse of the shipping trade, they were almost astonishingly unwanted on the sales or charter market where they languished with no takers. They even suffered the indignity of being advertised for sale in the common press, even in Canada and Australia, like liver salts or bicycles.

|

| Almost brand new and superb vessels, Heliopolis and Cairo still did not attract a single bid when auction in May 1909. Credit: Lloyds List |

As they had with their start in the railway business, Mackenzie & Mann saw an opportunity. It was eventually settled on to purchase Heliopolis and Cairo which would realise all their ambitions at a stroke. Never before or since would a new trans-Atlantic service be introduced with vessels of such qualities. Although they required substantial alterations to make a pair of Mediterranean express packets into North Atlantic liners, their speed, superb accommodation and newness would give CNR a trans-Atlantic service second to none from the onset. Indeed, one that would not only cater to the emigrant-oriented Canadian trade, but also to the wider American midwest market for which Montreal was more convenient than New York. Here, CNR were anticipating what CPR aimed for with Empress of Britain of 1931. And in many respects, Heliopolis and Cairo were to do for CNR what they had done during their brief careers with Egyptian Mail Steamship-- introduce new standards of speed and style for owners new to the shipping trade on a new route built around fast and direct rail connections at both ends to offer an express service second to none.

"Make no little plans, but spend very little" could have been the credo of Mackenzie & Mann in summer 1909. And in a buyer's market, they got the deal of the age. Having been stuck with Heliopolis and Cairo since October 1908, Fairfields were eager to be rid of them. In the end, Mackenzie & Mann bought them in late August 1909 for £415,000 (recalling they cost £606,000 to build two years previously) yet paid only £100,000 cash, the balance being settled by promissory notes for £90,000 and £225,000 of debenture stock in Canadian Northern with the further binding proviso that the stock could not be sold for less than £95 per £100 of stock. Four years later, this price was not still not realised. CNR did contract Fairfields for the refitting of Heliopolis and Cairo at about £20,000 each, but it would be a long time before the Govan firm cleared the books on these vessels.

After a summer of speculation, rumours and premature announcements, it finally appeared that Fairfield Shipbuilders had, at long last, found a buyer for two of their finest ships. On 31 August 1909 it was reported that Heliopolis and Cairo had been sold to Northwest Transport Co. with the intention of running them between Hamburg, Rotterdam to Halifax and New York in summer and "in the Mediterranean" in winter.

|

| Credit: Star-Phoenix, 9 September 1909. |

Obviously plans were fluid enough that all this was forgotten by early autumn. It was wisely decided to let Uranium Line cater to the Continental-Canada emigrant trade from Rotterdam and, instead, employ the former Egyptian Mail sisters on a first-class, express England-Canada run to directly compete with CPR's new Empress of Britain and Empress of Ireland. This new line, Canadian Northern Steamships, was founded in Toronto on 21 October 1909. However, Heliopolis and Cairo were still purchased by the firm of Mackenzie, Mann & Co.

Canadian Northern engaged Capt. Gregory as their Maritime Superintendent and he was also tasked with bringing both liners up to the Clyde from Marseilles. On 5 November 1909 Cairo arrived in the Clyde, "much interest was shown in the Egyptian mail steamer Cairo when she reached the Tail-of-the-Bank this forenoon, the stately appearance of the vessel arresting attention." (Greenock Telegraph). On the 26th, Heliopolis came in as well. Fairfields was so busy with work that there was no room for the ships in their own basin at Govan so both were instead worked on in Shieldhall basin.

Canadian Northern announced on 9 December 1909 their intention to commence operations between Montreal and Liverpool that spring. The corporate structure was tidied up in February 1910 when Heliopolis and Cairo were "sold" for £403,000 by Mackenzie, Mann & Co. to Canadian Northern Steamships.

Whilst the ships were being refitted, more interest was being centered around the potential British terminus port with the focus turning to Bristol and specially the new closed dock facilities (opened in July 1908 by the King & Queen) at Avonmouth. Although the terminal port was initially stated as being Liverpool, it had not been settled on and CNR Third Vice President D.H. Hanna paid an extensive visit to Avonmouth on 25 February 1910 followed by lunch with the Lord Mayor of Bristol and Alderman Twiggs, chairman of the Bristol Docks Committee. Southampton, Liverpool and Glasgow were also inspected and under active consideration.

|

| Formal notice published in Lloyd's List, 7 March 1910, announcing the change of names of Heliopolis and Cairo to Royal Edward and Royal George, respectively. |

On 10 March 1910 it was announced, with some sensation, that the terminal would indeed be Avonmouth. Whereas Bristol had been a major immigrant port of embarkation for America in the early to mid 19th century, it had long since been eclipsed in the age of steam by Liverpool and Southampton. The choice was based on the brand new port of Avonmouth itself and the Great Western Railway's commitment to build a new £30,000 quayside railway station with express boat trains to London Paddington with prospect of a one-hour 45-minute journey time. As such, the decision was in the context of Cunard's use of Fishguard, Wales, and American Line using Plymouth as a "short cut" for London-bound travellers. It also made the Bristol-St. Lawrence crossing the shortest Atlantic run with but three and half days actually in the North Atlantic. In some respects, it was the trans-Atlantic version of the Egyptian Mail ship/train combination for which Heliopolis and Cairo had been built for.

|

| Souvenir postcard for Royal visit of the King & Queen to Avonmouth in H.M.Y. Victoria & Albert to open the Royal Edward Dock on 9 July 1908. Credit: Bristol Archives. |

|

| Rendering of the new GWR quayside terminal for the Canadian Northern ships. Credit: Bristol Times & Mirror, 30 April 1910. |

Lloyd's List of 17 March 1910 featured Canadian Northern advertisement and noted that the line was referred to as The Royal Line and the ships renamed Royal George (ex-Heliopolis) and Royal Edward (ex-Cairo). Moreover, the initial sailings were announced: Royal Edward on 12 May followed by Royal George on the 26th. New offices for the line opened in Baldwin Street in Bristol. In Canada, Canadian Northern pointed out that "the name 'Royal Line' selected by Mackenzie and Mann was decidedly appropriate, since not only would a regal service be given, but the boats would sail from the King Edward wharf at Montreal to the King's Docks in Bristol, while the steam train run by the Great Western Railways would be known as the 'Royal Route'" (The Gazette, 21 March 1910).

|

| The first advertisement for CNR's "Royal Line" in the Canadian Press. Credit: The Gazette, 29 March 1910. |

Canadian Northern Vice President Hanna, prior to sailing from Liverpool in Mauretania on 2 April 1910 denied reports his line was planning a rate war to lure passengers to the new service, but that the company would not join the Atlantic Conference.

The first week of April 1910 a cargo of coal from Wales arrived at Glasgow intended for Royal Edward and Royal George which were scheduled to go on trials the next week. Both ships took their turns being drydocked in preparation and shared Fairfield's busy fitting out basin with the cruiser H.M.S. Glasgow, destroyers H.M.S. Grasshooper, Mosquito and Scorpion and Australian destroyer H.M.A.S. Parramatta.

|

| Early British press advertisements for the Canadian Northern's "Royal Line". |

On 8 April 1910 Lloyd's List reported that Capt. Roberts, formerly of Dominion Line, had been made Master of Royal Edward and Capt. Harrison, formerly of Allan Line, to command Royal George.

NEW ROUTE TO CANADA. THE ROYAL LINE The officials of the Canadian Northern Steamships (Limited) Royal Line are actively engaged in making the necessary and final arrangements for the sailing of the first steamer, the Royal Edward, which leaves Bristol for Quebec and Montreal on May 12. The various departments of the line are working with great enthusiasm, and the outlook appears to be of the very brightest character. Booklets describing and illustrating the accommodation of the steamers have now been published and circulated. From these some idea may be obtained of the magnificent accommodation provided by the Royal liners, which are described as the most luxurious and the fastest running from this country to Canada. Travellers to the Dominion are enabled on the Royal Edward and Royal George to rent what are aptly termed ocean fiats during the passage across the Atlantic. On the other hand, the accommodation for third-class passengers is quite unrivalled and costs no more than that of other steamers. On application to the Royal Line offices at Bristol, London, or Liverpool, sailing lists and copies of the company's publications can be obtained.

Lloyd's List, 13 April 1910

|

| Cover of the 'Atlantic Royals', the exquisite 24-page brochure designed by one of Canada's oldest graphic design firms, Grip Ltd. of Toronto. Credit: Queen's University, Toronto |

link to the complete Atlantic Royals brochure:

https://archive.org/details/atlanticroyalsro00cana/mode/2up

ROYAL SISTERS

The ships were now a really beautiful pair with grey hulls and red boot-topping, white forecastle, and their funnels yellow with dark blue tops. Fine-lined with good sheer, stepped back bridge front and well proportioned masts and funnels, they were at the time, in my opinion, the smartest looking pair of moderate-sized liners on the North Atlantic.

J.H. Isherwood, Sea Breezes, October 1957

|

| R.M.S. Royal Edward: North Atlantic express liner |

It would be an understatement to say that Heliopolis and Cairo were not among Fairfield Shipbuilding's more successful contracts before the Great War. Irrespective of their innovation, quality and performance not to mention beauty, they were the bane of the balance books for a considerable period. Indeed, it was a coup that they found buyers given their route specific specification. Even so, the firm lost a considerable sum on the pair, but also added to their reputation by accomplishing a speedy, cost-effective and, by and large, very successful conversion of the pair to a route and service as different from that originally conceived for them as imaginable.

A FLOATING HOTEL. By invitation of Mr. William Mackenzie, president of the Canadian Northern Railway, some 150 guests joined the Royal Edward at Greenock on Thursday morning. The vessel was, of course, then in her native waters, for she and the Royal George were befit by the Fairfield Shipbuilding Company at Govan. It is here, too, that after their brief acquaintance with the blue Mediterranean they have undergone certain structural rearrangement designed to fit them for the Atlantic trade. This rearrangement, it may be noted, has been less considerable than some people anticipated. Those whose privilege it was to voyage in the Cairo, and to enjoy her twentieth-century luxury, find all its main features preserved in undimmed splendour in the Royal Edward. The regal character of her spacious public apartments, the refined comfort of her suites de luxe and of her cabin accommodation generally, is maintained in all the fullness which made her noteworthy among recent Clyde-built ships. Her seven decks, linked up by an electric lift and laced by convenient staircases, remain a distinctive and imposing feature. Indeed, about the only obvious change, apart from some slight shortening of the funnels, is the removal from the boat deck of the kitchens, pantries, and stores formerly associated with the cafe lounge whose roof forms the flying bridge.

Lloyd's List , 30 April 1910

As the Fairplay report indicated, the refit that was given to the two ships was not nearly as extensive as suggested in both contemporary reports and later accounts. It was, however, not a facile effort to adopt two high-speed, light-displacement express short-sea Mediterranean, almost all First Class "ferries" (as Heliopolis and Cairo were so described upon their introduction) into North Atlantic three-class liners whilst still retaining their chief assets: their high speed and excellent cabin accommodation. In addition, there was the desire to mitigate what had been their principal deficiency: their rolling. It's perhaps telling that all this was not afforded a lot of coverage in the extensive shipping and engineering journals of the day, giving an impression that Fairfields, whilst carrying out a very successful and impressive "do over" of the ships they had only launched a few years previously, were not keen on drawing further attention to their troubled beginnings or any deficiencies in their seaboat qualities.

It is also a curious fact that, uniquely, these two ships, designed by Francis Elgar and built by Fairfield, were now to be directly competing with Empress of Britain and Empress of Ireland, created by the very same naval architect and yard and just a year apart. The CPR ships defined the sturdy, high freeboard North Atlantic liner on its most exacting route in terms of weather and seas whereas the Egyptian Mail ships were just as tailored for their diametrically different route and trade conditions.

Mitigating rolling and improving stability entailed reduction of tophamper and increasing their draught. The magnificent original funnels were completely replaced. In addition to their towering height, their double flue design (the outer flue ventilating the firerooms with Mediterranean conditions in mind) doubled their effective weight. They were replaced by conventional rounder profile stacks one-third shorter than the originals which, retaining a jaunty rake and profile, did not detract from their appearance.

|

| Royal Edward coming alongside at Avonmouth giving a good idea of her relative size, her short forecastle, big superstructure and shorter new funnels. Credit:©Bristol Museums, Galleries and Archives |

In addition, the original Café Lounge, situated right forward under the bridge, was changed in function from a full service grill restaurant to a role suited to its name, a lounge for the serving of light refreshments. This enabled the complete removal of half the Boat Deck deck house starting at the forward funnel casing taking with it the café seating either side of the casing and the galley and pantries aft. Right aft on the same deck, the steel covered sheltered seating area facing aft was removed as well. If anything, these alterations gave more unencumbered open deck space although its utility on their new North Atlantic route was doubtful.

|

| The forward well deck of Royal Edward gives a good idea of the relative size of these ships. This was used as Third Class open deck space. Credit: Getty Images. |

Increasing the load draught was accomplished through the necessity of increasing their bunker and cargo capacity. A new forward transverse coal bunker was created to add 500 tons (good for two days steaming at full service speed) extra capacity and their cargo space modestly increased, including 1,400 cu. ft. in reefer space. The speed of these ships and their modern refrigerated storage made them very popular with the export Canadian butter and cheese trade although they were never heavy carriers of conventional cargo.

Additionally, the plating and scantlings forward were significantly beefed up to enable safe navigation in the light ice floes common on the St. Lawrence route in early spring and late autumn. Their forward freeboard was high enough but right aft, they were very low and open. Consequently, a somewhat old-fashioned but effective "turtleback" was added right aft to keep the new Third Class covered deck drier and more protected. The open railings in this section were also replaced by solid bulwarks.

|

| Cairo as built |

In the end, the loaded draught was increased by about 3 ft. to 28 ft. And when all said and done, it could be argued that the more exacting sea conditions encountered on their new North Atlantic route more than countered the desired effects from these alterations. In the end, they still earned, fairly or not, the monikers of "Rolling Edward" and "Rolling George" and there was no getting around they were simply not designed or built for their new trade.

It is also worth noting that none of these alterations seems to have diminished their speed or performance, indeed they were run "flat out" and put in some remarkable performances despite being dogged by remarkably bad luck in having other record breaking crossings spoilt at the end by fog in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. There is every probability, however, that their fuel consumption rose proportionally with the increase in displacement and draught. In actual service, they weathered the worst the North Atlantic could throw at them and came through with flying if salt-streaked colours, faring no worse than liners built for such conditions. That one survived a head-on collision with an iceberg and the other a serious grounding was further testament to their toughness.

|

| R.M.S. Royal Edward showing to advantage these ships' light and attractive livery, unique on the North Atlantic route during this era. |

R.M.S. ROYAL GEORGE

Rigging Plan

credit: National Maritime Museum, courtesy Douglas Shirley

(LEFT CLICK on image to view full size scan)

R.M.S. ROYAL GEORGE

Deck Plans

(c. 1920)

credit: Facebook Group Ocean Liner Deck Plans

(LEFT CLICK on image to view full size scan)

|

| A Deck |

|

| B Deck |

|

| C Deck |

|

| D Deck (showing the two added Third Class dining saloons fore and aft and new Third Class smoking room forward) |

The ships' accommodation was re-arranged but, significantly, it was not expanded in real capacity. Originally having a total of 1,000 berths (710 First and 290 Second), they would now accommodate 1,114 (344 First, 210 Second and 550 Third Class). The allotment of these berths was obvious and uniquely generous on the North Atlantic in that Second Class enjoyed what had been First Class accommodation and almost all of Third Class was berthed in what been Second Class cabins. In addition, Third Class had unequalled sanitary and bathing facilities compared to other liners where the few toilets and baths were often two or three decks away from the cabins. This and the undiminished speed of these ships gave the "Royals" their marketing "niche" and they were unmatched on the North Atlantic for their accommodation in all classes. And if the Third Class was especially impressive, the First Class was without equal for the range of public rooms, lavishness of the decor and appointments.

One aspect of these ships, and certainly among their most appealing-- the superbly decorated and luxurious interiors, beautiful furnishings and impressive architecture-- from their Egyptian Mail days was entirely unchanged and quite without equal on the North Atlantic, certainly for intermediate sized vessels and indeed, compared to the largest and finest "Floating Palaces". As such, they were milestone Canadian route liners, the first to compare and compete with the biggest New York liners in their accommodation, style and speed. In many respects, they anticipated Empress of Britain of 1931 in drawing custom to the St. Lawrence route from the American Midwest and New England.

Imagine the most complete, the most nobly furnished hotel you have ever seen. Apply the conditions of its splendor to the limitations imposed by the cleverest shipbuilder, and you have still fallen short of the charm which fits the Royal George and the Royal Edward like a garment.

All the great eras in furniture-making and decorating have been laid under contribution to the enjoyment of the passengers. Whether you walk the spacious decks, sit in the secluded alcoves and watch the rolling waves, or occupy yourself in the public or private apartments, there is a prevading sense of elegant comfort and swift progress to 'the other side.'

The Atlantic Royals

|

| First Class Café-Lounge |

There is rare delicacy and refinement in the appointments of the first class café. It is in the Regnecy style, panelled in exquisitely carved oak. The furnishings are faultless examples of Louis XV style. The lighting deepens the general effect of artistic restraint; the port are coved and curtained, so as to temper daylight to the old crimson pink.

|

| First Class Cafe-Lounge |

In the centre of the long steel deck-house of the promenade deck is the First Class Music Room, wherein are faithfully reproduced some of the finest exemplars of the Louis XVI period. A particularly elegant feature is the a semi-circular setteed recess framing a magnificent statuary chimney piece. The ivory white woodwork, carpets, curtains and coverings of pastel blue, the crystal effect of leaded glass from the circular dome above, combine in a brilliant decorative effect.

|

| Credit: Bristol Archives, The Vaughan Collection |

|

| First Class Library. |

The library, an abode of opulent repose, is a delightful reminiscence of the Louis XV period. Rich tapestries adorn the dark oak panelling of the walls. Delicate mouldings and rich, restrained carving suggest the elusive charm which characterizes the famous chateau at Romboullet, decorated while France was rioting in the Revolution and its Napoleonic aftermath. Grey oak and uncommon shades of green in the upholsterings help to produce an air of settled, reflective charm.

|

| First Class Smoking Room |

As tobacco was introduced to the English-speaking world when Elizabeth was Queen, it is fitting that the smoke-room, with its two thousand square feet of floor space, should be a fine example of Elizabethan style, down to the minutest detail of upholstering. The oak panelled walls, and the venerable oak beams of the ceiling, with antique hanging lanthorns, suggest the baronial hall of an English hero of the Armada. The seats, luxuriously covered in a red of a curious red shade, give an effective touch of color to a faultlessly appointment apartment. A series of ingenious little bays seem to have been specially prepared to invite those genial confidences which often make of the smoke-room a citadel of unconquerable laughter.

The first class dining saloon is a great achievement in ocean-going aids to good cheer. Old voyagers will remember, by blessed contrast, the long narrow tables which used to make the best-served saloons look like charitable institutions. The very aspect of things here is an incitement to socialbility. The largest tables holds but sixteen people-- a manageable family party-- and all around are sheltered nooks in which are no more than five can foregather.

The refectory is wide as the ship, and one-seventh of her length. Over its centre is a lofty dome-- not a decorated skylight raised a few feet above the ceiling. Immediately above is the library, which gets its central light from the circular-headed windows that enclose the well and perform the extra function of helping to ventilate the dining room. Above these are the life illuminants of the lounge; so that when come to the centre of the grand saloon, you look up and again to the real dome, which opens unobscured to the fleckless sky.

If are expert in such things you will discern that the carving is modelled upon the exquisite art of Grinling Gibbons, whose work is in the Chapel at Windsor, in the choir of St. Paul's, at Chatsworth, and half a dozen other places of the Old Nobility. Proportions have had to be modified, of course; but the details are all of the eighteenth century.

The double swing doors that communicate with the great staircase are of richly figured mahogany, nut brown and wax polished. They contrast agreeably with the boldly carved mahogany architraves and carved motif above, subdued to cream color to harmonize with the walls and general woodwork. The upholstery is of rich Genoa velvet, and the seats, carpets and curtains are in old rose pink.

|

| Credit: Bristol Archives, The Vaughan Collection. |

|

| First Class Children's Dining Room |

|

| First Class Entrance and Staircase. |

For those to whom stairs are a vexation there are elevators; but, in the main, life on shipboard is leisurely enough for the passenger to derive all possible advantage from the exercise of ascending and descending. In the principal stairways of a liner the naval architect has special opportunity of defeating the restrictions which nature and mechanics have imposed upon him. In the Royal George and the Royal Edward the first class entrances and grand staircase are everything that can give a sense of dignity and spaciousness.

|

| Credit: Bristol Archives, The Vaughan Collection |

|

| Credit: Bristol Archives, The Vaughan Collection |

|

| First Class de luxe cabin bedroom. Credit: NMM |

|

| First Class suite sitting room. Credit: NMM |

|

| First Class suite bathroom (note the bath mat still reads "E.M.S.S.Co" and these photos date from August 1911) |

Forward and aft of the music room are state-rooms accommodating 133 passengers. Here are cabins de-luxe containing sitting rooms, bedrooms and bath-rooms, all self-contained and delightfully fitted. The decorations are of mahogany and satinwood in Sheraton style, with varying color schemes.

|

| First Class cabin de luxe. |

|

| First Class cabin. Credit: NMM |

|

| First Class Promenade Deck |

|

| First Class Boat Deck |

|

| Second Class cabin |

The second class passengers on the Royal Line have staterooms equal in airiness, fixtures, and comfort to those of the first class. A criticism of them by other steamship people is that they are so roomy and luxurious that will create a demand that cannot be met. But the Royal steamers were meant to set the pace for really modern travel across the Atlantic. The dining saloon extends the width across the ship, well forward. It is in fine mahogany, with revolving chairs, and is furnished with a piano. The arrangement for quick service of meals are of the very best.

There is an admirable lounge for the lady passengers, and a smoke room spacious and well arranged and furnished, for those who smoke. The library is stocked with a splendid assortment of the best books, for every good taste in reading. Indeed, there is nothing lacking for the traveller who likes luxury to be added to convenience.

An important feature in shipboard pleasures is the deck promenade. The second class on the Royal boats is remarkably good.

For the new Third Class, two dining saloons were added forward and aft on D Deck as well as a smoking room right forward on the same deck.

|

| Third Class four-berth cabin (one of the newly built ones, most of the accommodation was former Second Class and far superior to this). Credit: NMM |

|

| Third Class four-berth cabin. Credit: NMM |

Refitted, renewed and ready to embark on new careers, Royal Edward and Royal George were immensely attractive and appealing vessels, perfect to realise the Atlantic ambitions of the Canadian Northern as well as help to usher in a wonderful, true pre-war heyday of the Canadian route.

|

| The official line portrait of The Royals, artist W. Kitzig. They were uniquely light and colourful looking trans-Atlantic liners for their era and all the more attractive for it. |

As predicted the Royal Line steamers of the Canadian Northern are turning out to be wonders in speed and fully live up to the expectations of Mr. MacKenzie and the Canadian Northern officials.

The Ottawa Citizen, 15 June 1910

The steamers of the Royal Line plying the Atlantic between Bristol and Montreal are making good. They are the fastest steamers on the Canadian route and are meeting with great favor with the travelling public.

The Victoria Daily Times, 11 August 1910

1910

NEW CANADIAN TURBINES. Three weeks hence the palatial triple-screw turbine steamer Royal Edward will inaugurate the new express service between Bristol and Canada. Her sister ship, the Royal George, follows a fortnight later. Owned by the Canadian Northern Steamships (Limited), these two 12,000-ton liners were constructed on the Clyde. and it is safe to say that they will be among the most luxurious vessels afloat. They will carry first, second, and third class passengers, and for each class every possible comfort has been provided. The vessels have seven decks, I these being linked up by an electric passenger lift. There is a café lounge on the boat deck. The steamers are equipped with the Clayton fire-extinguishing apparatus, and are thus as safe from fire as it is possible to make them. They are also fitted for wireless telegraphy. The Royal Edward and Royal George promise to be the fastest steamers in the Canadian trade, for they are known as 20-knot boats. From every point of view they may be expected to prove highly popular with the travelling public.

Lloyd's List, 21 April 1910

On 22 April 1910 it was announced that Royal Edward would leave the Clyde for Avonmouth on the 28th and have among her passengers the Lord Mayor and members of the Dock Committee. Departing Greenock at noon, her guest list of some 250 included Lord Mayor Bristol, C.A. Hayes, Sir William Howell Davies M.O. and Lady Davies, Alderman Twiggs (Chairman of the Docks Committee), Mr. W. Mackenzie (President off the Canadian Northern Railway Company), Admiral and Lady Markham and many press and trade representatives. Gale conditions the previous evening had moderated but it remained cold and blustery.

"After leaving Greenock the Royal Edward proceeded down the Firth of Clyde, and off Skelmorlie she ran her speed trials, the very satisfactory average of over 21 knots being recorded. The voyage to Avonmouth was commenced in cold but bright weather, a stiff north-westerly breeze blowing. Despite the heavy sea, the liner made excellent progress, and averaged 21 knots up to the time she approached Holyhead. She will thus be the fastest steamer on the Canadian service. There was a complete absence of vibration or rolling during the run." Bristol Times and Mirror, 29 April 1910.

|

| An immaculate, fresh from the shipyard Royal Edward approaching Avonmouth on her delivery voyage. Credit: Bristol Archives, The Vaughan Collection. |

|

| Royal Edward approaching the gates to the Royal Edward Dock. The GWR station is on the left. Credit: Bristol Archives, The Vaughan Collection. |

|

| One of the four-card set by Harvey Burton of Royal Edward's triumphant arrival at Avonmouth. Credit: author's collection. |

|

| no. 3 in the set. Credit: author's collection. |

Royal Edward arrived at Avonmouth at 9:00 am on 29 April 1910, greeted by a fleet of dressed overall as were other other vessels in the port. "The vessel received a great welcome at Bristol whose citizens are displaying the very greatest interest in everything associated with the new line. The occasion was celebrated by the Bristol Dock's Committee by the opening, by the Lord Mayor, of their new passenger station at Avonmouth. The facilities provided by this station places the port in an unrivalled position in respect to the easy transfer of passengers and their baggage from train to steamer and vice versa." (Lake's Falmouth Packet and Cornwall Advertiser, 29 April 1910). It was added that "There is much speculation as to her speed. In shipping circles it is generally recognised that she will make an easy record passage, and win the blue-ribbon of the Atlantic on the Canadian route. There is, of course, no question that these two 'Atlantic Royals' are the most luxuriously fitted steamers running to Canada."

|

| No. 1 in the Harvey Barton photo card set of Royal Edward's maiden arrival at Avonmouth. Credit: author's collection. |

BRISTOL AND CANADA. ROYAL EDWARD'S CRUISE Yesterday Bristol came a little nearer to the realisation of its desire for the inauguration of a fast passenger lino across the Atlantic. The triple-turbine steamship Royal Edward, which is to open the service to Canada on May 12, reached Avonmouth from the Clyde, and in so doing made her first acquaintance with what in future will be her home port on this side. It matters not that the Royal Edward is formally registered at the port of London. Henceforth she and her sister turbine boat, the Royal George, will be regarded as Bristol ships, reviving is truly auspicious fashion that old-time association between the West of England and the North American continent of which Bristol's citizens are so justly proud. Needless to say, yesterday was for them a red letter day. The bunting which the vessels in the Royal Edward Dock displayed was not merely suggestive of the deference rightly due to a monarch among ships. It was the outward and visible sign of local satisfaction that a courageous municipal dock policy is beginning to reap its reward.

|

| Credit: Western Daily Press, 29 April 1910 |

Amid the preparations and excitement building for the inauguration of the new service came the shock and sadness of the death of H.M. King Edward VII on 6 May 1910. He had opened the Avonmouth Docks in 1908 and, of course, the name Royal Edward was bestowed on both the dock and the ship that would inaugurate the first North Atlantic service from it.

Under auspicious circumstances, the 12,000-ton triple turbine liner Royal Edward cast off her moorings at 8 o'clock last evening at Avonmouth Dock. In so doing she opened the Canadian Northern Railway Company's fast mail and passenger service between Bristol and Quebec and Montreal. With the tug Bea Prince towing ahead, and the tug The King astern, she Famed out to sea, loudly cheered by large crowds of people. The Royal Edward carries 50 first-class, 150 second-class, and 500 third-class passengers, a large proportion being British emigrants of a promising type. Her crew number 288. The Royal Edward will maintain a speed of 19 knots across the Atlantic, and is due to arrive at Quebec early next Wednesday afternoon.

Lloyd's List, 13 May 1910

|

| Part of the crowd on the quayside at Avonmouth to see Royal Edward off on her maiden voyage. Note one of the special GWR trains in the background. Credit: Getty Images. |

As an indication of the efficiency of the new service, on 12 May 1910 the train from London Paddington for First and Second Class passengers departed at 4:15 p.m. and had its passengers alongside and aboard Royal Edward in plenty of time for her maiden sailing at 8:00 p.m. The train for Third Class had left earlier at 11:00 a.m. and there was also a direct train from Bristol Temple Meads for West Country passengers to the quay at 6:25 p.m.

|

| First Class gangway during embarkation on Royal Edward's maiden voyage. Credit: Getty Images. |

The Royal Edward, the pioneer of the new Royal Line of steamers between Avonmouth and Canada, sailed from our port last evening. We wish her and all on board 'Bon Voyage' and we would couple with this particular steamer and trip the whole undertaking which has so auspiciously begun… The Royal Edward had started for Quebec with a rich argosy of hopes and expectations. The people of Bristol, the Canadian people, and the hundreds of voyagers she is bearing towards a new land are interested in the success o her voyage and of the venture which it inaugurates.

Bristol Times and Mirror, 13 May 1910

|

| Third Class passengers in the forward well deck of Royal Edward as she sails on her maiden voyage from Avonmouth. Credit: Getty Images. |

There remained time for a hurried farewell, and then preparations were made for sailing. On the quay and piers was gathered a crowd of three or four thousand people, and the passengers lined the side of the steamer, waiting to wave farewells to their friends on the shore. 'Are you ready, Mr. Rowlands?' shouted an official on shore to the well-known pilot on the bridge; and the ropes were cast off, and, with the aid of the two tugs, the stately looking liner proceeded out of the docks at ten minutes past eight. Cheers were raised on shore, and were responded to by those on board, and the vessel had a Royal reception as she passed through the lock into the roads, and then, dispensing of the tugs, proceeded on her eventful voyage on her own steam.

Bristol Times and Mirror, 13 May 1910

Not everyone was favourably impressed with the departure of the new ship or, rather the port's treatment of it as a report in Lloyds List of 14 May 1910 related:

A regrettable example of " how not to do it " was afforded in connection with the undocking of the Royal Edward. The vessel, which was proceeding out of dock whilst it was still daylight, has a large number of heavy rivets showing along her sides. Big vessel as she is, she lay close up to the stone-faced wall of the lock. Now anyone at all conversant with the handling of big vessels in dock waters would have recognised the desirability of using cork or rattan fenders to prevent friction as she moved out of the lock. Apparently, however. the authorities overlooked this matter in some measure, and the result was that the port side of the liner. to the extent of some feet, rubbed heavily against the lock wall. Sparks testified to the severity of the friction, and it was evident that some of the rivet heads projecting from the liner's side suffered damage. All this might have been prevented by the employment of a few men with cork fenders. Mr. Girdlestone. the manager of the docks, was on the quay, and it is surprising to me that in his presence more care was not taken in handling the ship. Bristol admittedly wants to attract to her fine new dock all the trade she can, but if she wants big steamers to come to the port she will need to take a few lessons in handling them. Shipowners do not like to have the paint scored off the sides of their vessels—to say nothing of something worse.

On the morning of 17 May 1910 Royal Edward passed Cape Race and a Marconigram from the vessel reported that she had been steaming at an average of 19.75 knots, the fastest yet recorded on the Canadian run and that "throughout the trip she has behaved extremely well." The next day Capt. Roberts wired: "The Canadian Northern turbine Royal Edward made a remarkably good first trip across the Atlantic. Has broken the record for the fourth day's run with 472 miles. The previous runs for 278, 447, 440 and 472 miles." CNR's Vice President Hanna replied with a telegram to the press: "Royal Edward broken all Canadian records, day ending noon Tuesday made 480 knots averaging over 20.45 knots per hour, but lost some time owing to fog. Avonmouth to Father Point, 5 days 22 hours 41 minutes."

Having made such fast passage across, it was frustrating that Royal Edward's final approach through the Gulf of St. Lawrence was retarded a good 12 hours by fog and smoke in the lower gulf. She finally came into Quebec in the small hours of 19 May 1910:

At two o'clock this morning the Royal Edward, the Canadian Northern flagship, nosed into her moorings here on her maiden voyage from Bristol to Quebec. She entered Quebec harbor at 1 a.m., at full tide, but was an hour in docking. Even if her name was Edward, and the Royal Edward at that, she was queen of a royal line and dignified. Her long length glided gracefully through the dark waters, her lighters gleaming high and revealing a symetrical slate blue body. On the farther shore, over Levis way, twinkled stationary gleams. It was a sight worth seeing, with few there to see.

From land to land, from Avonmouth (Bristol) to Father Point, she came in five days, twenty hours and forty minutes, an average of eighteen and three-quarters knots an hour. On Tuesday [17 May] she average twenty an hour for the twenty-four hours.

Ottawa Citizen, 19 May 1910

Royal Edward left Quebec City at 7:00 am and a party of newspaper men joined her for the passage to Montreal. "The trip up the river, although the Royal Edward was not hurried at first, was later made a rattling speed, and proved a most enjoyed experience to all those on board, the perfect smoothness of the vessel of the vessel and her splendid equipment in every respect rendering the voyage a memorable one." (Gazette). She arrived at Montreal at 6:30 pm, docking, appropriately enough, at the Royal Edward Pier. "The Royal Edward made a most imposing sight as she approached Montreal her great bulk and unusual height quite dwarfing any other vessels along the wharves, and making the process of pulling her into the dock a very slow one. " (Gazette).

|

| Back when such things mattered, Royal Edward's record breaking maiden crossing was news in the Canadian press and a public relations coup for the infant service. |

The Royal Edward pulled in under most happy auspices, having made the fastest trip between England and Quebec of any commercial steamship, with the fastest daily average, and also the biggest day's run yet made on the Canadian Atlantic highway. More than that, the big turbiner proved herself not merely a very fast vessel, but also an extremely comfortable one, riding steadily on the Atlantic, while her engines ran so easily that it was with difficulty passengers could discover that they were moving at all, and there none of the oscillation and throbbing that is marked a feature on vessels run by reciprocating engines. In fact, Captain Roberts, her commander, stated that he had commanded no less than thirteen trans-Atlantic steamers at various times , and the Royal Edward was easily the most comfortable and steady sailor of them all. Capt. Roberts was the more emphatic in his statement to this effect because it had been reported that the Royal Edward, having been built for the Mediterranean tourist trade, would not prove suitable for the heavier waters of the Atlantic-- a prophecy which both officers and passengers lost time in disproving.

Gazette 20 May 1910

|

| Credit: Western Daily Press 25 May 1910 |

On 21 May 1910 the ship was inspected by invited guests and as the Gazette related: "afternoon tea was served on board to the ladies and the inner wants of the sterner portion of the guests were also amply provided for" while the general public was admitted aboard on Sunday, "expressions of admiration were heard on all sides, and the company is not likely to lack patronage when the time comes for the ships to sail on their homeward voyages."

Departing Montreal on 26 May 1910, in spite of having to sail at half speed until reaching Sorel, Royal Edward managed to break all records on the passage from Montreal to Quebec, doing the run in 7 hours 50 minutes.

|

| Royal George comes into Avonmouth for the first time on her delivery voyage from Greennock. Credit: author's collection. |

Meanwhile, Royal George had completed her trials and delivery voyage. Commanded by Capt. Harrison, she sailed from Greenock at 3:00 pm on 17 May 1910 with only a few aboard, including Capt. Gregory, Royal's Marine Superintendent and F.B. Girdlestone, General Manager of Avonmouth Docks. For the delivery voyage, Fairfields provided the 52 trimmers and firemen who returned to the Clyde on a special train. Captain Gregory told the press that the trip from Greenock was "a delightful one and that splendid weather was experienced all the way."

|

| Royal George's maiden arrival at Avonmouth on 18 May 1910. Credit: author's collection. |

The West Country press ensured that Royal George's introduction was not afforded the relative obscurity given "the second sister" when she arrived at Avonmouth from the Clyde on 18 May 1910:

Quite a large crowd of spectators journeyed down to Avonmouth yesterday afternoon to witness the arrival of the Royal George, the sister ship to the Royal Edward. It was a magnificent day for the purpose, and those who stood upon the pier heard and looked across the channel to the Welsh hills that formed the horizon, could not failed to be impressed with the fact, and the beauty of their surroundings. Scarce a ripple disturbed the smooth surface of the water that shimmered beneath the glare of a brilliant sun, and craft that clothed the sea in places added to the picturequeness of the scene. The Royal George was moving slowly in Kingroad. She left Greenock on Tuesday afternoon at three o'clock, and passed Lundy Island yesterday morning at about four. Her speed had been 20 knots, which was exactly what she made on trial over the measured miles. From Ilfracombe she jogged quietly along, stemming the tide, and drifting along with it. As she lay in Kingroad yesterday afternoon she presented a delightful picture, inspiring admiration in the minds of all who were lining the quay walls. Pilot Joseph Mitchell was aboard, the tugs King and Sea Prince were soon at their persuasive work of bringing the liner into the entrance channel.

Western Daily Press 19 May 1910

|

| Royal George coming into Avonmouth for the first time. Credit: author's collection. |

Two expresses ran from Paddington, the first conveying third class passengers, the total number being between 300 and 400. The majority of those on the train were men of the best agricultural class, who have made arrangement to settle on the land in the far West. A large number took with them their family, and in the other cases there were parties of young farmers setting out to seek fortune in the Dominion, while there were also not a few young women who have secured situations as domestic servants. It is very rare that a steamer carries such a splendid complement of men and women as those who joined the Royal George. After an inspection of their cabins and public rooms, they expressed themselves delighted with the accommodation, the luxury of which it is impossible to exaggerate.

Warwick & Warwickshire Advertiser, 28 May 1910

"Soon after half-past seven all the passengers and luggage were aboard, and the Royal George was ready for her journey. She was tugged gently away from the lock wall into the middle of the lock, and at a minute or two to eight Captain Watkins-- who controlled the arrangements at the dock in the absence of Captain Harvey-- gave the signal to start.

Yielding to the gentle persuasion of the tugs, she glided neatly out into the broader water between the dock piers. The South Pier afforded many hundreds fine positions from which to view the liner. The last farewells were shouted from shore to boat, and most of those on the latter seemed in excellent spirits. Some had climbed a little way up the rope ladder of the second mast and sung cheerfully as the space between them an the Old Country widened. … After clearing the entrance way the liner was headed down the Channel by the tugs. In ten minutes the liner had been towed clear of the docks. Their work was done; the hawsers were slipped, and the Royal George was left to her own resources. The water in her wake showed signs of the disturbing influence of her propellers. For a moment or two the 12,000 tons hardly seemed to yield to the influence of the blades hardly seemed to the influence of her propellers. As she lay this listlessly there came the sound of cheering across the waters. Two of Messrs. P. and A. Campbell's steamers had run special trips to give people the chance of seeing the great liner under weigh. The decks of both seemed black with people, and right heartily they cheered. Their feelings were re-echoed by those on shore, and even those hardened old seamen who captain the 'small fry' of the channel, and whose sentiments are expected to withstand the stirring effects of even this majestic sight, so far forgot themselves as to mingle with the cheers the shrill shrieks of their steam whistles. The crowd on the pier head lessened as the vessel drew away, but a number remained to see the last of her, and the end was a darker blotch relieved by a few twinkling lights on the dark background of the fast gathering evening shadows away down Channel.

Western Daily Press, 27 May 1910

|

| Royal George leaving Avonmouth showing to advantage of the "turtleback" added to her stern during the refit. Credit: author's collection. |

Fog made Royal George's maiden voyage as slow as her sister's had been swift and again it was fog in the Gulf of St. Lawrence that retarded her progress. She did not pass Fame Point until noon on 1 June 1910 and finally docked at Quebec the morning of the 3rd. "owing perhaps to the fact that she came up the river in the early morning light, showed her to even better advantage as she approached her moorings.." (Gazette).

"The Royal George sailed from port for the first time yesterday morning, and very fine she looked as she slowly warped away from her berth at the Canadian Northern pier and swung into stream. The majority of her first-class passengers elected to join at Quebec, amongst them being the Governor-General and his party.." (Gazette, 10 June 1910)

|

| Royal Edward sails from Avonmouth, 9 June 1910. Credit: Getty Images. |

On her second westbound crossing, Royal Edward continued to show her speed. Departing Avonmouth at 7:00 pm on 9 June 1910, she arrived at Quebec at 3:15 p.m. on the 15th and proceeded to Montreal at 6:00 pm where she docked at 11:00 a.m. the following day. This was in spite of slowing down in the Gulf owing to a large ice floe in the fog. This beat Empress of Ireland's best time by 50 minutes. Her best day's run was 482 miles, the best recorded yet on the Canadian route. "This performance of the Canadian Northern steamers, said a C.N.R. official today, "quite justifies the post-master in his decision to give the Royal line a share of the mail carrying contract, and should be an important factor in securing to Canada a large portion of the ocean passenger traffic which is at present going via New York at higher rates without the advantages of the superb St. Lawrence route." (Ottawa Citizen, 15 June 1910).

|

| Credit: The Province, 18 June 1910 |

Frustrated again by the elements, in this case, two days of rough weather upon departure from Avonmouth, Royal George still clocked an average of well over 400 miles a day and docked at Montreal the evening of 30 June 1910 on her second arrival at the port. It was remarked that, like her sister, a daily news sheet was published on board "which was kept as up to date as the exigencies of the wireless service would allow. Sports and concerts were made features of the trip, and were entered into with gusto by all on board." (Gazette, 1 July 1910). Among her passenger disembarking at Quebec was William Jennings Bryan and Mrs. Bryan returning from the Missionary Congress at Edinburgh. Declining to discuss politics, he instead lauded the beauty and the interest of the St. Lawrence route.

The next day was Dominion Day as reported by the Gazette: "The harbor presented a gay appearance yesterday, every ship lying at the wharves being dressed with bunting in honor of Canada's birthday. The Royal George made a particularly brave showing, and was the centre of attraction for many hundreds who had not hitherto had a chance of inspecting at close quarters the newest addition to the large fleet of vessels which make Montreal their terminal port. Lying as she does bow on to the waterfront, her yacht-like lines can be seen to the best advantage without going to the shed at all, and this point of vantage was crowded all day with interested spectators."

The advent of Royal Edward and Royal George on the Canadian route precipitated a new round of rivalry as reported by the Vancouver Daily World 5 July 1910:

A keen fight or the Canadian mail contract is evidently to be made by all the steamship companies in the North Atlantic trade. The advent of the Canadian Northern Railway company's steamships Royal Edward and Royal George-- the first of which has already broken two speed records-- has made the other companies take quick action to retain their supremacy, and several orders for new vessels capable of high speed have been announced.

Success seems to have come to the new company immediately from the despatch of the first of its vessels which are recognized as the fastest plying in the Canadian trade. The Royal Edward holds the blue ribbon for this route by making a run from Bristol (Avonmouth) to Quebec in five days seventeen and a half hours. Her previous best time, which she made on her maiden voyage, was a also a record for the southern route.

Her sister ship, the Royal George, has just inaugerated a fortnightly mail service, given to the company by the federal government. This put the Canadian Northern in a strong position and will probably have some bearing when the present contract expires.

The Allan Line, holder of the contract, has ordered a 22-knot vessel, and hopes thereby to retain the whole of the contract. At present, by an understanding between the two companies, it is shared with the Canadian Pacific Railway Company.

The latter company is also expected to enter the lists, as it has long been considering an extension to its fleets. Report also has it that the White Star-Dominion combination has ordered two express boats in this connection, but no confirmation is at present forthcoming.

|

| British market advertisement for the First Class trade, the Royals being unquestionably the finest ships in this class then on the Canadian run. |

With the largest excursion yet organised in the Dominion for a European trip, Royal George sailed from Montreal on 7 July 1910 with 700 members of the Sons of England, 500 of whom were from Toronto. The group was waved off by the Mayor of Toronto and members of the City Council as well as President William Mackenzie and other officials of the Canadian Northern.

Royal George arrived at Montreal shortly after 6:00 pm on 28 July 1910 and, astonishingly, encountered yet more foggy conditions in the Gulf delaying her for half a day and ruining any chances for a record passage. "For the first two days out of Bristol, really bad weather was encountered, and even the oldest salts on board were ready to admit they were getting the benefit of a real gale. The ship is said to have behaved splendidly, however, for in spite of the high seas which were running, she hardly rolled at all, though, of course, she could not be expected to have been quite steady. She brought over a full list of passengers, many of whom were evidently loath to leave the ship, so comfortable had they been." (Gazette, 29 July 1910).

Meanwhile, her sister continued to break records it seemed with every crossing. Leaving Avonmouth on 4 August 1910 at 8:00 pm, Royal Edward docked at Quebec at 11:05 am on the 10th. This set a new record of 5 days 20 days and a land to land record of 3 days 14½ hours. She left Quebec at 1:30 pm for Montreal. Her best day's run was 496 miles or 21 knots and her lowest was 160 miles or just over 19 knots. She had bested Empress of Britain's previous record by 5 hours 30 minutes.

|

| Credit: The Province, 24 August 1910 |

Royal Edward sailed from Montreal on 18 August 1910 among her passengers was the Hon. W.L. Mackenzie King, Minister of Labor, and future and long serving Prime Minister of Canada. Not aboard, despite rumours to the contrary, was the notorious Dr. Crippen, being returned to stand trial for the murder of his wife in one of the most sensational crimes of the era and one of the most ocean liner centric. He would eventually be returned to face justice aboard Megantic.

Among those sailing in Royal George from Avonmouth on 16 August 1910 was the Band of the Grenadier Guards. They would return aboard Royal Edward after their Canadian tour on 15 September. And, yet again, the ship was fogbound in the Gulf, encountering so much of it off Red Island on 24 August that she was forced to anchor and wait for it to lift before continuing to Quebec where she docked the following evening. Among those among was Sir Edward Morris, Premier of Newfoundland, and Lady Morris. Sir Edward praised the ship to the press: "Nothing could surpass the accommodation and the attention given to the to wants and comforts of the passengers."

It was announced in Halifax on 24 August that the Nova Scotian port would be Royal Line's winter terminal port. The first three sailings from Avonmouth would be 22 November (Royal Edward), 3 December (Royal George) and 17 December (Royal Edward) and from Halifax 7 December (Royal Edward), 14 December (Royal George) and 27 December (Royal Edward).

When Royal George next arrived in Canada (docking at Montreal on 25 August 1910) she had the largest number of passengers yet carried on the new service, a total of 1,014 (235 First Class, 225 Second Class and 555 Third Class), including 150 returning Sons of England tour members. This was exceeded by Royal Edward which sailed 1 September from Avonmouth with 1,024 passengers, 270 First, 203 Second and 551 Third.

The ship continued to be bedeviled by fog in the Gulf and once again what had actually been announced as a record passage by the line turned to disappointment when Royal George docked at Quebec a little before 5:00 pm on 21 September 1910 instead of 9:00 am as expected having had to slow down owing to fog.

It was not only Royal George that was impacted by autumn weather and at 2:00 pm on 6 October 1910 a rather storm battered Royal Edward finally reached Quebec, more than half a day late. She sailed for Montreal at 4:30 pm and did not dock at Montreal until the following morning. This occasioned a piece in the Gazette on the 8th praising the vessel's performance in the worst seas she had yet encountered:

The Royal Edward, which arrived here yesterday from Bristol, experienced nothing but a succession of gales of almost tropical fury all the way across the ocean. She is said to have behaved exceptionally well in the very heavy weather she met with, and through obliged to slow down for hours at a time, all her officers spoke very well of her as a heavy weather boat. Her passengers were loud in their praises when they landed here, declaring that while at times the seas which washed over her decks were mountainous, the ship hardly even staggered under the succession of blows showered on her. So severe was the weight of the water at times which landed on her decks, that many minor casualities were reported, but the most serious of these were the fracture of a leg and in another case of an arm. Both of these fractures occurred to members of the crew, and the extent of injuries suffered by passengers was a few bruises.

|

| The issue of the ships' stability remained a touchy one as indicated by the dueling press pieces concerning Royal George's eastbound crossing in early October 1910. |

The Canadian Northern have led the way in the matter of flying the Canadian flag upon Atlantic steamboats, both the Royal George and the Royal Edward sailing under those colors today. They are the first two ocean going vessels to be registered in Canada, their port of registry being Toronto, but it is though that the lead thus given will result in a great increase in the number of ships owning a Canadian port as their home.

The Gazette, 29 October 1910

For the last time that first season, Royal George sailed from Avonmouth for Montreal on 9 November 1910. This was the first occasion one of the Royals carried mail westbound and a contract with the Postmaster General would be inked early in the coming year. After her by now traditional "Detained by fog in the Lower St. Lawrence", Royal George, which was due to dock at Quebec the evening of 14 November 1910, did not arrive until the morning of the 17th with 17 First, 77 Second and 260 Third Class. The later were disembarked there and during examination, a Russian bound for Wisconsin, was found to be ill with cholera. All Third Class passengers were immediately re-embarked and after loitering off Quebec for the day, Royal George was ordered back to the Grosse Isle quarantine. Poor weather prevented landing the passenger at Grosse Isle for fumigation for a full day.

It was decided to land the Third Class passengers on Grosse Isle for quarantine for five days. This was done on 19 November 1910 by ships boats also carrying over bedding and provisions, 20 stewards, one stewardess, the Third Officer and an Asst. Purser. As it was, conditions on the island were dire with the facility dating from 1835 and the buildings in very poor shape, all making for most miserable experience. The infected passenger, it is happily noted, made a full recovery.

After being fumigated, Royal George and her First and Second Class passengers were permitted to proceed the evening of 19 November, docking at Montreal just after 5:00 a.m. on the 20th. Scheduled to sail for Avonmouth that day, she had her departure pushed forward to the 23rd and even that required round the clock work to get her unloaded and then coaled and provisioned. Royal George was able to get away by noon on the 23rd. As a result of the very bad publicity, the Canadian Parliament came up with an appropriation of $50,000 to build new quarantine facilities on Grosse Isle.

|

| Before her first year was out, Royal Edward broke another record, this time to Halifax on her first crossing there. Canada finally had a record breaker all her own. |

When Royal Edward left Avonmouth for Halifax for the first time on 23 November 1910, she had 14 First, 77 Second and 170 Third Class passengers and 590 bags of mail. She set another maiden voyage record, crossing in 5 days 7 hours 30 minutes, breaking the previous mark by several hours, arriving on the 29th. The following day Canadian Northern Vice President Hanna hosted representatives of the Maritime Provinces to luncheon aboard to celebrate the first call at Halifax.

Vexed again by the weather gods, Royal George instead battled strong head winds and seas all the way across on her first winter passage to Halifax, arriving there on 12 December 1910 after clocking 6 days 45 minutes for the trip and landing 241 passengers, 541 bags of mail and 630 tons of cargo. She returned to Avonmouth on the 22nd; "Considering the time of the year, the voyage was a good one. The Royal George encountered some heavy seas, but she behaved admirably and made excellent time." (Bristol Times & Mirror, 24 December 1910).

|

| A wonderful Garrett photo card of Royal George "Westward Bound" off Portishead. Credit: Bristol Archives, The Vaughan Collection. |

It had been an eventful and successful first year for Canadian Northern's Royal Line and these superb vessels were finally fulfilling their expectations. The Gazette of 10 December 1910 stating: "They have succeeded in the first year of not only capturing the blue ribbon of the Atlantic in shape of the record for the fastest passage between port and port, but in establishing a merchant marine for Canada. The ships which they operate as the first ocean going vessels to fly the Canadian flag." In addition, their advent accelerated both the delivery of mail and the move to broaden the contracts on both sides of the Atlantic to encourage faster ships. The first shipment of mail carried by Royal Line from Canada landed on 16 June totalled 150 bags, the last delivered in 1910 on 22 December comprised 400 bags. The new westbound arrangement began on 8 November with 280 bags and the last in December totalled 600 bags.

In 1910, Royal Edward completed 16 crossings carrying 7,644 passengers (5,238 westbound and 2,406 eastbound and Royal George completed 16 crossings carrying 7,294 passengers (4,626 westbound and 2,668 eastbound) for a total of 14,938 passengers on 32 crossings (16 round voyages).

1911

|

| Credit: National Post, 7 January 1911 |

Looking spic and span after her thorough overhaul in dry dock, the Royal Edward yesterday sailed from Avonmouth for Halifax, N.S., after a stay of about a month in the docks. The weather was a contrast to that which has been enjoyed on these occasions, but yesterday was a miserable day, the rain coming down literally in sheets, and, driven by a strong south-westerly wind, very soon drenched those who had congregated on the lock side to wish their friends good-bye.

The Canadian Northern Company, on this trip, have sent out a specially conducted party of domestic servants-- the first party under a new scheme which they are developing to help the emigration of this class off workers, who are in great demand in Canada, and especially the Western Provinces.

Bristol Times & Mirror, 12 January 1911

If ships can summon up memories of past duties, then the former Cairo surely missed the Mediterranean on this first crossing in 1911. Arriving at Halifax on 18 January, "the captain reports he did not see sun, moon, nor stars from the time he left Bristol. He encountered head gales all the way over, the hardest passage he ever experienced. The coldest weather was 8 below zero." (Gazette, 19 January 1911). Halifax harbour was frozen for the first time in 35 years.

On 25 January 1911 it was reported in the Gazette that Canadian Northern had chartered the Cunarder Campania "to handle the increased immigration this winter… already the Royal George and Royal Edward sailings for March have been filled and there are very few vacant berths on either ship."

|

| Advertisements for the Royal Line's first winter season from Halifax to Bristol on "The Atlantic Royals". |

In February 1911 The Post Office announced a new contract with Canadian Northern for Royal Edward and Royal George to carry mail westbound. Hitherto, the line only had a Canadian contract for eastbound post. The new westbound contract, replacing the previous route via Southampton and Queenstown, was reckoned to accelerate delivery by two days.

The steamer Royal Edward, which arrived today from Bristol, brought more than a hundred prospective bridge from England, Ireland and Scotland. All were bound for the Canadian Northwest. They were in charge of a matron appointed by the steamship company. She will accompany them as far as Toronto where special representatives will accompany them further West. Most of them will settle in the vicinity of Regina.

It had been reported that a young woman resembling Ethel Clare Leneve, the woman who figured so prominently in the Crippen case, had boarded the steamer at Bristol an was bound for the Canadian to meet her prospective husband. A search of the vessel, however, failed to reveal any trace of her.

The Province (Vancouver), 15 February 1911

When Royal George docked at Halifax late in the evening of 28 March 1911 it was claimed that she had maintained the fastest average run from Britain to the port, 18.3 knots. She landed 890 passengers, almost all settlers bound for Western Canada.

On her last trip to Halifax that season, Royal Edward docked the evening of 11 April. She clocked 5 days 18 hours 39 minutes. "Good weather was experienced to Cape Race, and after that heavy westerly gales were encountered and heavy seas were shipped, but the ship sustained no damage." (Gazette). She landed 950 passengers, almost all settlers bound for western Canada.

That St. Lawrence season started rather tentatively with persistent ice conditions in the Gulf. On 27 April 1911 the Allan liner Sicilian encountered an field ice off the Magdalens and turned about and made for Halifax. This time Royal George was lucky with the weather and coming on to the same point just hours later found the ice had been dispelled by strong winds and she was able to continue into the River, becoming the first liner of the 1911 season. Indeed, she was, rather uniquely, the first vessel of any description to win the distinction. She docked at Quebec that day. All her passengers were landed there as the was still enough ice up river so that she would not make it to Montreal until the 29th. "With flags flying the steamship Royal George arrived in port here [Montreal] at 7 o'clock this morning, and as a result Captain Harrison has won the distinction of being the first commander to open up navigation on the St. Lawrence." (The Victoria Daily Times). Capt. Harrison was presented with the customary silk hat awarded to the first captain of the season. His ship was also the first liner to depart Montreal, on 3 May, with 350 passengers aboard including a party of 12 Canadian officer cadets en route to London and the Coronation.

This first arrival of the season also introduced a new and improved method of coaling the ships at Montreal, devised by Royal Line's newly appointed Marine Superintendent, Capt. F.J. Thompson, RNR, formerly master of Uranium Line's Campanello, as explained his wonderful series of articles in Sea Breezes, September-November 1960:

The "Royals" were perhaps the first liners to take bunker coal in Montreal through side ports and consequently no facilities for doing this. During the previous season they had used lighters on the off side and carts which dumped coal on the quay. This had to be shovelled in from the shore side resulting in slow and expensive work, apart from the coal dust permeating the cargo even when passengers were embarking. To overcome this I proposed booming the ships off from the wooden pier, and bringing lighters on the inside as practised by most of the liner companies in New York.

Not having seen the pier at Montreal, it was soon apparent on my first visit that conditions were entirely different. There were no steam winches or other power on the pier to boom the ships off and on making my number to the Port Warden I was told that the ships lay with 50 ft. of their sterns beyond the end of the pier.

This was discouraging but after consideration I felt that the responsibility must be accepted in order to improve the bunkering arrangements. After making representation to the Harbour Commissioners instructions were to issued to them that all ships were to reduced speed to a minimum on passing the C.N.R. Pier. In making the contract for bunker coal it was stipulated that the contractor should provide lighters with winches and with stump derrick posts to under the booms, between the ship and pier.