Part Two: H.M.S LETITIA (1939-1941)

H.M.T. LETITIA (1941-1944)

H.M.C.H.S. LETITIA (1944-1945)

T.S.S. EMPIRE BRENT (1946-1951)

T.S.S. CAPTAIN COOK (1952-1960)

The sequel to Letitia's fulsome pre-war career was doubtless the most varied, valiant and valuable. Serving as an Armed Merchant Cruiser in the early days of the Battle of the Atlantic and, later, as a transport, she participated in the build up to and in the offensive phase of the war at the landings in North Africa and Italy. Letitia went on to serve Canada as its largest hospital ship, repatriating wounded Canadian forces.

The last phase of her career found Letitia fulfilling the true purpose of the passenger liner, facilitating the movement of people towards new lives... Canadian and German POWs, Canadian war brides and their babies, Polish displaced persons, refugees, migrants, Dutch evacuees and military personnel from Indonesia, India's first Olympic Team... amid the upheavals of the troubled post-war world. Far from the glitter of the "Superliners," Letitia carried out her myriad roles quietly and modestly. But as Letitia, Empire Brent and Captain Cook, she played a memorable part in the lives of many in Canada, Australia and New Zealand as well as Britain and the Netherlands.

H.M.S LETITIA

BRITISH ARMED MERCHANT CRUISER

Beginning the next phase of her life, Letitia sailed with convoy TC 16 (which included the CGT liner Cuba and Sud Atlantique's Pasteur) from Halifax on 15 December 1941 for Liverpool where she arrived on Christmas Day.

Letitia next sailed on one of the major "W.S." (for Winston Special) fast convoys carrying troops to the Middle East via Freetown and South Africa. Leaving Liverpool on 10 January 1942 for Freetown, Letitia, with 2,232 troops, joined Britannic, Laconia, Orontes, Otranto, Pasteur, Stirling Castle, Strathmore, Strathnaver and Viceroy of India. Freetown was reached on the 25th and the convoy proceeded to Durban, arriving on 13 February. From there, Letitia sailed independently back to Cape Town and Freetown and returned to the Clyde on 14 March.

Autumn 1942 and the focus shifted to an offensive war starting with Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa by American forces supported by British naval elements. In support of this, Letitia sailed from the Clyde to Oran in Convoy WS24P/KMF1 on 26 October with American troops and at Gibraltar on 6 November, senior American officers embarked. An enemy submarine was sunk en route.

Hitherto, the only other Canadian hospital ship in the war had been Lady Nelson and upon completion, Letitia was hailed as "the world's most up-to-the-minute floating hospital" when she was introduced to the press alongside in Montreal on 2 November 1944. Her military commanding officer, Lt. Col. A.L. Cornish and her master, Capt. James Cook, showed off her new features and explained the $3,250,000 conversion, the most extensive of its kind done in a Canadian yard.

Though the Letitia was making her maiden voyage as a floating hospital and the patients had been prepared to undergo a certain amount of discomfort until things got shaken down, there was a unanimity in expressing satisfaction at the comfort of the trip, the food and the medical service on the well-appointed craft.

Her next voyage took Letitia further afield and on new duties when she sailed from Halifax on 4 January 1945 for New York. There, she embarked German POWs for exchange for Allied ones at Marseilles. Letitia left New York on the 7th and arrived at Marseilles on the 24th. Her German POWs were exchanged for an equal number of British/Dominion ones with both groups repatriated via neutral Switzerland by sealed hospital train. Many of the Allied POWs came from camps in Silesia. Letitia embarked 6 stretcher cases and 665 walking cases and sailed for Liverpool where she arrived on 1 February.

Letitia left Liverpool on 13 February 1945 and returned to Halifax on the 22nd with 700 invalided Canadian forces. Subsequent arrivals on 21 March with 746 aboard and 16 April (from Falmouth) disembarked 740 more and on 20 May she came into Halifax with 743 “representing every regiment in Canada,” some who had not been home in five years.

With Victory in Europe, the Canadian Government pledged to have every wounded Canadian serviceman, numbering some 53,000, home by 31 July 1945. To help achieve this, the British hospital ship Llandoverry Castle was assigned to join Letitia and Lady Nelson. Letitia came into Halifax again on 17 June with 725 casualties and again on 16 July, two days late due to fog, with 733 and "As the big ship came into her dock, a band on the pierside struck up "Roll Out the Barrel" and spontaneous burst of cheering came from the men lining the rail." (Gazette).

H.M.C.H.S. Letitia completed ten voyages and repatriated 6,703 wounded Canadian and American forces.

Having departed for Britain on the 29th, Letitia had only made it as far as William Head when she again developed engine trouble and was forced to return to the yard. Following repairs, Letitia resumed her voyage on 4 January 1946. At the time, it was rather hopefully reported that she would “return to the Montreal-U.K. run sometime this summer.”

So it was reported the day after 900 migrants (half of whom were Scots) trooped aboard Empire Brent at Glasgow’s King George V Dock on 31 March 1948. They arrived at Fremantle on 2 May 1948, greeted by pipers playing on the quayside, where 45 disembarked. The local press reported effusive praise for the vessel and conditions aboard "Migrants said the ship's officers and crew did everything to make the trip pleasant", "The food was excellent and was at least twice the British ration" and “Ship was heaven”. There had been an outbreak of chicken pox aboard, affecting 40 passengers, mostly children, which kept the ship’s surgeon and one nurse busy. She arrived at Melbourne on 7th, and Sydney the 10th.

Back on her more familiar duties, Empire Brent cast off again from Glasgow on 29 November 1949 for Australia. En route she had had put into Malta on 6 December to land a critically three-year-old child. She had been in the ships hospital for four days with an abdominal complain which suddenly became acute. Upon the ship's arrival in Adelaide, a message was received that the child had recovered and been discharged. Empire Brent docked at Sydney on 7 January in the middle of another dockers strike and the ship’s 200 stewards had to unload the 500 passengers luggage.

At a function aboard yesterday Mr. I. Harvey S. Black, a director of Donaldson Brothers and Black Ltd., managers of the Captain Cook, pointed out the New Zealand Government had spent £750,000 to bring the ship to the condition in which she had been inspected that day by a large party of press representatives and others. A great number of improvements had been made, including the complete overhaul of the Thermotank system. She was to be regarded as a passenger ship for the use of young settlers going to New Zealand.

Starting the latest and last phase of her long life, the former Letitia sailed from Glasgow as Captain Cook with 1,093 migrants on 5 February 1952. Among her passengers were 429 family parties, 360 single men, 153 single women and 155 volunteers for the New Zealand Forces. The maiden voyage was not without its problems with workmen aboard finishing some aspect of the conversion and making good defects, boiler trouble forced a longer at Curaçao and, always a problem, the supply of fresh water ran out a few days before reaching Wellington on 15 March rather than the 9th as scheduled. Nine days off the New Zealand coast, off Pitcairn Island the ship's doctor safely delivered a prematurely born baby, named James after Captain James Cook, the master of the vessel and Robert Lindsay after the doctor who delivered him. Captain Cook sailed from Wellington for Glasgow on the 22nd.

Her second voyage began from Glasgow on 13 May 1952 with 1,092 settlers who arrived in Wellington on 18 June. They comprised 483 persons in family groups, 371 single men and 141 single women, 96 service personnel and one fare paying passenger. Of the assisted migrants, 245 were destined for Auckland, 73 for Hamilton, 98 for Christchurch, 100 for Dunedin and 190 settled in in Wellington. From July 1947 to 15 May 1952 a total of 18,214 assisted immigrants came to New Zealand, including 4,584 displaced persons. When Captain Hobson landed 448 settlers at Wellington on 1 September, it brought New Zealand's population to the two million mark, having doubled in the last 44 years.

Amid the preparations for the Coronation of H.M. Queen Elizabeth II that June, it was announced on 11 April 1953 that Captain Cook would represent New Zealand at the Fleet Review off Spithead during her U.K. turnaround. On the 17th Prime Minister Holland announced that arrangements were being made to enable New Zealanders visiting Britain for the Coronation to attend the Review aboard the ship. Special trains would leave London on 14 June and the participants would embark the ship that evening to see the fireworks and the review the following day, returning to London by special train on the 16th. The cost was set at £12 pounds per person and a maximum of 600 persons could be accommodated.

Captain James Cook was among the New Years 1954 Honours List O.B.E.’s in recognition of a lifetime service at sea starting at age 16, serving in the Royal Navy Reserve in the First World War and more than 30 years with Donaldson Line. Retiring on 1 April, he was afforded a dinner in his honour aboard Captain Cook at Glasgow on 25 March 1954 attended by line, port and emigration officials as well as the Deputy High Commissioner for New Zealand, R.M. Campbell. He had captained the ship’s first eight voyages which had carried some 9,000 migrants to New Zealand.

Like a long absent but still remembered old friend, the former Letitia returned to Montreal on 29 April 1955. It was, in many respects, a return to the old days when Letitia was new rather than a now 30-year-old veteran. Commanded by Capt. Alexander Bankier, she docked at her once familiar Shed 2.

Captain Cook sailed from Montreal on 2 May 1955 with 507 passengers, but at the last minute, her planned call at Liverpool on the 11th where 217 were to disembark, had to be cancelled owing to a tug strike there.

On the other hand, the charter of the T.S.S. Captain Cook to meet the demand for tourist travel during the season, showed a disappointingly small profit and the last few voyages resulted in considerable loss.

Without doubt 1957 was Captain Cook’s “year” and no passenger ship had a more varied or valuable 12 months. If a liner, by definition, is about the movement of peoples across the oceans and forming an integral link in the lives, fortunes and fates of her passengers, Captain Cook earned a unique place in 1957 during which the ship and her passengers were caught up in the upheaval of the increasingly fraught post-war world.

Another northbound diversion saw Captain Cook arrive at Singapore on the last day of 1956. There, she embarked 850 British servicemen and their families and sailed for Liverpool on 3 January 1957. With the Suez Canal still closed, she sailed via Colombo (8th), Cape Town, Freetown and Dakar before finally arriving at Liverpool on the 22nd.

The sailing of Captain Cook for New Zealand on 19 March 1957 was delayed when a fault was found in one of her boilers. Amid a strike by shoreside engineers, no repairs could be effected except by the ship’s own engineers and she eventually was able to sailed on the 23rd. Her 1,050 passenger spent the extra days alongside using the ship as their hotel. She arrived at Wellington on the evening of 28 April instead of the following morning as planned to land a sick passenger.

When the charter of New Australia lapsed and was not renewed by the Australian Government in September 1957, Captain Cook became the very last Ministry of Transport ship engaged in the migrant trade.

In Jakarta, another 1000 Dutch nationals streamed aboard the migrant ship. Captain Cook. Troops with rifles and pistols stood by as sobbing women, clutching their children and hastily packed possessions, climbed the gangplank. Friends carried elderly women and invalids to the berths.

Captain Cook sailed from Tandjong Priok on 21 December 1957 and called en route at Colombo on the 27th. Two ladies, aged 77 and 69 years old, died during the course of the long voyage, but on 13 January, in the middle of the Mediterranean, a baby girl was born, five weeks prematurely and weighing but three pounds, was housed in a hastily contrived incubator.

With her passengers shivering in the unaccustomed cold of what was suddenly “home,” Captain Cook docked at the Javakade in a snowy Amsterdam in the pre-dawn hours of 21 January 1958. H.M. Queen Juliana boarded Captain Cook at 9:00 a.m. to the cheers of her passengers and was introduced to Capt. Bankier. Addressing all those aboard over the tannoy, the Queen welcomed the evacuees and said all would be done to ease their settlement to what was for most a strange and unknown country. The Queen went on to visit the sick in the ship’s hospital and met the social workers who had tended to the passengers during the voyage. At 10:30 a.m., Her Majesty disembarked Captain Cook, after affording the elderly liner her first and only Royal Visit.

When Captain Cook sailed from Glasgow on 8 October 1958 she took away another full list of 1,051 passengers, 800 from England, 115 from Scotland and 21 from Denmark who landed at Wellington on 14 November. It was announced at the time that on her homeward voyage she would again call at Christmas Island to bring back British personnel engaged in nuclear tests there to Southampton. About 500 R.A.F. officers and men returned home on 5 January 1959.

Commanded by Capt. Colin Porteous (who was Third Officer and officer of the watch of Athenia when she was torpedoed), Captain Cook left Glasgow on 24 September 1959 on her 25th voyage to New Zealand. Among her passengers were 11 from Denmark, 13 from Switzerland and the rest from the U.K. There were 173 families and 247 children, 57 teenagers, 132 between age 3-12, 38 between age 1-3 and 20 under 1. The passenger list was rounded out by 258 British single men and 189 British single women.

Thus ended the Letitia's 35 years of almost constant work in all parts of the world. She had made a great name for herself both on the Canadian and New Zealand routes. Last of the Donaldson passenger ships, she certainly became the best known of them all.

Emigrant Ships To Luxury Liner, Peter Plowman, 1992

North Star to Southern Cross, John M. Mayber, 1967

BRITISH ARMED MERCHANT CRUISER

Letitia docked at Montreal on 5 September 1939 from her aborted crossing to Britain and 24 hours after her sister finally sank after being torpedoed. Letitia was a ship with a score to settle and lost little time in doing so.

Like many British liners of the inter-war era, including the similar Cunard “A” class intermediates, Letitia and Athenia had been designed with possible conversion into Armed Merchant Cruisers in mind, specifically the provision of stiffened decking and supports at eight designated positions for six-inch naval guns. In some respects, these were the best suited liners to this still unlikely role if only because of their low superstructures and single funnel and uptakes.

The envisaged use of these vessels was primarily that of convoy escorts and fulfilling patrol functions. Armed but not armoured, they were very vulnerable to attack by "proper" surface warships. Between 1939 and 1940, 56 passenger liners, all twin-screw with speed of at least 15 knots were requisitioned as AMCs. Fifteen of these were lost to enemy action by 1941. And despite the courageous sacrifice of H.M.S. Rawalpindi and H.M.S. Jervis Bay as convoy escorts, the Armed Merchant Cruiser was a turn of the century concept that did not last more than two years into the Second World War.

On the 9 September 1939 Letitia was requisitioned by the British Admiralty to be converted as an Armed Merchant Cruiser. The next day the Dominion of Canada declared war on Germany.

Fittingly for a ship that had served Canada in peace, Letitia was prepared for war in a Canadian yard at the Vickers plant in Montreal. She and P&O's Rajputana (at Esquilmalt, B.C.) were the first AMC converted in Canada and in the case of Letitia it was accomplished in eight weeks.

Eight Mark VII six inch guns were bolted to the existing gun supports, four on the port side and four on the starboard side. These were supplied by shell and cordite bag magazines constructed in the fore and after holds and fitted with simple electric davit hoists. The anti-aircraft armament consisted of a pair of two three-inch high-angle guns and a pair of twin Lewis guns on the bridge wings. A small gun director and range finder was fitted to upper bridge and height finder on a raised platform erected aft the funnel. Initially, none of the AMC’s were fitted with radar, but a Type 271 set was added around January 1940 along with depth charge throwers

So as not to impede the field of fire of her anti-aircraft guns, Letitia lost her kingposts and except for two pair aft, all of her remaining davits and boats. Quick release floats were hung on the superstructure. Permanent ballast was added and the voids in the lower holds filled with empty 55 gal. drums to provide added buoyancy in case of shell or torpedo damage.

Very little was altered in way of her accommodation and public rooms (indeed most of the latter remained more or less intact throughout the war) so if Letitia and her Cunard “A” class cousins also converted into AMCs were not very formidable warships, they were certainly more comfortable than most.

On 6 November 1939 she was commissioned under Captain William Reynard Richardson as H.M.S. Letitia, pennant number F16. Sailing that day for Halifax where she arrived on the 11th and as part of her working up, she test fired her main battery for the first time outside the harbour. She was manned by a mix of her original crew and mostly Royal Navy Reserve officers and ratings. Letitia joined the initially converted AMCs on Canadian convoy duty, Asturius, Ascania, Alaunia and Ausonia, and her first duty was escorting Convoy HX-10 departing Halifax for the Clyde on 25 November-4 December 1939 followed by HXF-15 from Halifax to Liverpool 6-19 January 1940.

On 6 November 1939 she was commissioned under Captain William Reynard Richardson as H.M.S. Letitia, pennant number F16. Sailing that day for Halifax where she arrived on the 11th and as part of her working up, she test fired her main battery for the first time outside the harbour. She was manned by a mix of her original crew and mostly Royal Navy Reserve officers and ratings. Letitia joined the initially converted AMCs on Canadian convoy duty, Asturius, Ascania, Alaunia and Ausonia, and her first duty was escorting Convoy HX-10 departing Halifax for the Clyde on 25 November-4 December 1939 followed by HXF-15 from Halifax to Liverpool 6-19 January 1940.

In a change of tactics, most of the Armed Merchant cruisers went off convoy escort duty in February to instead patrol the Northern Approaches, specifically the Denmark Strait between Iceland and Greenland. Assigned to the Northern Patrol, Letitia sailed on the first of 16 patrols on 29 January 1940 through 12 January 1941. From 9 May she was commanded by Capt. Edward Henry Longsdon. Reassigned to the Western Patrol, Letitia left the Clyde on 15 January 1941 for Halifax, her new base of operations.

Approaching Halifax in gale conditions on 7 February 1941, in an incident that recalled the loss of the original Letitia in the same waters, Letitia went hard around on Litchfield Shoal, about 100 yards off the shoreline. She was severely damaged and after the ensuing investigation, Capt. Longsdon was relieved of command and never again went to sea. After two days, Letitia was freed from the reef and towed into Halifax. However, with no dry dock space available, it was arranged for her to be repaired in the United States. On 24 May Letitia left Halifax under tow and arrived at Newport News six days later. Nominally, she was assigned to the Bermuda and Halifax Escort Force from March-April 1941 under Commander John Randolph James, but was out of service from 30 May-1 December 1941.

Approaching Halifax in gale conditions on 7 February 1941, in an incident that recalled the loss of the original Letitia in the same waters, Letitia went hard around on Litchfield Shoal, about 100 yards off the shoreline. She was severely damaged and after the ensuing investigation, Capt. Longsdon was relieved of command and never again went to sea. After two days, Letitia was freed from the reef and towed into Halifax. However, with no dry dock space available, it was arranged for her to be repaired in the United States. On 24 May Letitia left Halifax under tow and arrived at Newport News six days later. Nominally, she was assigned to the Bermuda and Halifax Escort Force from March-April 1941 under Commander John Randolph James, but was out of service from 30 May-1 December 1941.

By mid 1941, the era of the Armed Merchant Cruiser was at an end with more and better equipped escort ships coming into service and the tactical decision to provide convoys with escorts throughout their crossings.

So, whilst still at Norfolk, work on Letitia transitioned from repair to conversion to a more suitable role. On 7 June H.M.S. Letitia was decommissioned as an Armed Merchant Cruiser and stripped of her offense armament and her conversion into a troop transport began. This entailed stripping much of her below decks accommodation for berthing and mess areas as well as reinstalling king posts and cargo handling gear. It was at this time that she acquired her distinctive heavy lift king posts fore and aft. Her A Deck accommodation remained largely intact as did some of her original Cabin Class public rooms. She could berth as many as 3,000 men, but her normal capacity was usually 2,500 in addition to cargo. This was completed by 1 December and Letitia was now His Majesty’s Transport Letitia under the Ministry of War Transport.

So, whilst still at Norfolk, work on Letitia transitioned from repair to conversion to a more suitable role. On 7 June H.M.S. Letitia was decommissioned as an Armed Merchant Cruiser and stripped of her offense armament and her conversion into a troop transport began. This entailed stripping much of her below decks accommodation for berthing and mess areas as well as reinstalling king posts and cargo handling gear. It was at this time that she acquired her distinctive heavy lift king posts fore and aft. Her A Deck accommodation remained largely intact as did some of her original Cabin Class public rooms. She could berth as many as 3,000 men, but her normal capacity was usually 2,500 in addition to cargo. This was completed by 1 December and Letitia was now His Majesty’s Transport Letitia under the Ministry of War Transport.

|

| H.M.T. Letitia sailing from Halifax on 3 May 1942 with Convoy NA 8 for the Clyde which included the transports Andes, Batory, Cathay and Orcades. Credit: Nova Scotia Archives |

Now restored to something like her pre-war appearance save for her new, beefier king posts and still defensively armed, Letitia docked at New York from Newport News on 2 December 1941. By the time she left on the 8th, the United States was at war and two days later, she arrived at Halifax.

Beginning the next phase of her life, Letitia sailed with convoy TC 16 (which included the CGT liner Cuba and Sud Atlantique's Pasteur) from Halifax on 15 December 1941 for Liverpool where she arrived on Christmas Day.

Letitia next sailed on one of the major "W.S." (for Winston Special) fast convoys carrying troops to the Middle East via Freetown and South Africa. Leaving Liverpool on 10 January 1942 for Freetown, Letitia, with 2,232 troops, joined Britannic, Laconia, Orontes, Otranto, Pasteur, Stirling Castle, Strathmore, Strathnaver and Viceroy of India. Freetown was reached on the 25th and the convoy proceeded to Durban, arriving on 13 February. From there, Letitia sailed independently back to Cape Town and Freetown and returned to the Clyde on 14 March.

The next phase of her transport duties found Letitia plying a familiar course from the Clyde (Greenock or Glasgow) to Halifax with an eight-day passage. From 8 April to 22 August 1942 she made eight such crossings.

|

| H.M.T. Letitia at Halifax 3 May 1942. Credit: Nova Scotia Archives |

Autumn 1942 and the focus shifted to an offensive war starting with Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa by American forces supported by British naval elements. In support of this, Letitia sailed from the Clyde to Oran in Convoy WS24P/KMF1 on 26 October with American troops and at Gibraltar on 6 November, senior American officers embarked. An enemy submarine was sunk en route.

Letitia was part of the Center Task Force landing at Arzew, Algeria, 8-9 November 1942. Landing her troops there took the best part of four days with heavy swell and a shortage of landing craft. On passage from Oran back to Gibraltar she was attacked the night of 12-13th by a U-boat with two torpedoes just missing Letitia, one passing parallel to her and the other just astern. Sailing from Gibraltar to the Clyde on the 14th in Convoy MKF1Y, a concentrated U-boat attack ensured the next day in which the escort carrier H.M.S. Avenger and the troopship Ettrick were sunk. Letitia and the rest of the convoy reached the Clyde safely on the 21st.

Again North Africa bound, Letitia left the Clyde on 28 November 1942 and arrived at Algiers on 5 December and sailed for home five days later. A British destroyer was sunk in her convoy which reached the Clyde on the 18th.

After a refit, Letitia resumed service on 24 January 1943, sailing for Gibraltar, on the first of two round trips there. On 24 February she embarked the British Commando Regiment for Oran where she arrived on 4 March. She returned home via Gibraltar on the 14th with an eclectic passenger list including Poles, Free French forces, civilians and evacuees from Malta.

A change in climate followed when Letitia steamed west from the Clyde on 18 March 1943 for Reykjavick, Iceland. She made one roundtrip on this route followed by another also calling at the Faroe Islands which occupied her until 21 April.

After a round trip from the Clyde to Gibraltar 19 May-4 June 1943, Letitia was detailed to the Invasion of Sicily. For this, she sailed for the Clyde on 1 July for Algiers and than the landings at Augusta where her convoy was attacked by Italian aircraft on the 19th with two near misses. Letitia proceeded to Alexandria where she arrived on the 23rd.

August 1943 was spent shuttling between Alexandria, Syracuse, Algiers, Phillipville, Augusta and Malta where she embarked civilian evacuees. Shortly after leaving Malta, Letitia came under intense aerial torpedo attack, but once again was not not hit.

On 17 September 1943 Letitia sailed from Oran to Salerno for the later stage of landings there. The rest of 1943 was spent, after one voyage to Port Said and Alexandria in October, in the Western Mediterranean and North Africa. On 2 December 1943 Letitia arrived in Naples and towards the end of the year she sailed back to Egypt.

On passage from Port Said to Alexandria, Letitia heavily grounded on entering the harbour there on 18 January 1944 and did not leave until 17 February when she sailed for Naples. From 21 February through 27 March she shuttled between Naples and Oran. She was to have sailed for home from Naples in March, but one soldier aboard was diagnosed with smallpox and the everyone aboard had to be vaccinated. Worse, the ship was then reassigned to a voyage to Oran and return and hopes of a return home postponed.

On 8 April 1944 Letitia finally bade farewell to the Mediterranean and North Africa after a long nine-month deployment. She had aboard another very mixed passenger list including naval ratings, RAF personnel, Italian co-belligerents, German POWs, a French artillery company, Poles and Capt. D'Arcy's famous U.S. Military Band. Letita sailed from Algiers to Gibraltar (11th) and arrived back at Greenock on the 17th. She continued to Glasgow the following day and underwent 21 days of repairs from 19 April-10 May 1944. She then sailed to Montreal where she arrived 25 May to be adopted for her third wartime role.

|

| Fresh from her conversion, His Majesty's Canadian Hospital Ship Letitia at Montreal, November 1944. |

H.M.C.H.S. LETITIA

CANADIAN HOSPITAL SHIP

CANADIAN HOSPITAL SHIP

Shortly after the ice left the river this spring a huge sea-battered liner, her dull grey war paint scarred by winter storms in the north Atlantic and tropical suns, anchored in Montreal harbor amid all the usual secrecy of wartime ship movements. She was the tall SS Letitia, sister ship of the ill-fated Athenia-- first ship to fall prey to Nazi torpedoes, treacherously sunk on the first day of the present war.

Soon this famous liner, not a newcomer to Montreal, will sail forth again. This time she will go forth on missions of mercy. On her tall sides painted against a coat of white will be the huge Red Cross of a hospital ship.

The Gazette (Montreal) 26 June 1944

Letitia's career as a transport ended when she was assigned to the Canadian Navy as a hospital ship in March 1944. Arriving “home” at Montreal on 25 May, she was taken in hand by Vickers for her conversion.

|

| Detail of the above advertisement showing the hospital facilities and Letitia in Vickers' floating drydock near the end of her conversion. |

Hitherto, the only other Canadian hospital ship in the war had been Lady Nelson and upon completion, Letitia was hailed as "the world's most up-to-the-minute floating hospital" when she was introduced to the press alongside in Montreal on 2 November 1944. Her military commanding officer, Lt. Col. A.L. Cornish and her master, Capt. James Cook, showed off her new features and explained the $3,250,000 conversion, the most extensive of its kind done in a Canadian yard.

Under her protected hospital ship status, all of her defensive armament, gun tubs and other military equipment was removed. All of the remaining accommodation below decks was completely gutted and replaced by new 45-bed hospital wards. In place of the Tourist Class lounge aft on B Deck were two new air-conditioned operating theatres. In addition there were new dental labs, x-ray department, pathology lab and sterilising rooms. For homesick soldiers, there was a soda fountain that also offered “room service” to non ambulatory patients. The main dining room was for walking patients and a new galley could serve 3,000 passengers three times a day if needed. The original oak paneled Cabin Smoking Room became the officer’s lounge.

Externally, Letitia now glistened in hospital ship white with a four-foot-wide green band painted 25 ft. above water line and further marked by a series of green lamps below A deck encircled the ship and two illuminated crosses on her funnel.

|

| Credit: The Windsor Star, 3 November 1944 |

On 2 November 1944 H.M.C.H.S. Letitia was formally handed over to the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps alongside the Canadian Vickers pier.

Letitia sailed from Montreal on 6 November 1944 for the Clyde where she arrived on the 17th and then proceeded to Liverpool to embark her first returning Canadian wounded. Their voyage home got underway on the 26th and on 8 December Letitia arrived at Halifax with 700 casualties, the most to return home since the war started.

|

| Letitia alongside the Landing Stage at Liverpool. Credit: Author's collection |

Though the Letitia was making her maiden voyage as a floating hospital and the patients had been prepared to undergo a certain amount of discomfort until things got shaken down, there was a unanimity in expressing satisfaction at the comfort of the trip, the food and the medical service on the well-appointed craft.

Though the Letitia's two operating rooms were not busy on the first voyage, one major operation-- an appendectomy-- was performed on the way over.

Patients found the 13,000-ton vessel-- almost twice as large as the No. 1 hospital ship Lady Nelson-- had considerably more spare room, including several lounged for various classes of personnel. The Letitia also boasts a soda bar which provided "room service" for bed-ridden cases.

The Citizen, Ottawa, 9 December 1944

Letitia's second arrival at Halifax on 2 January 1945 disembarked 700 who continued their trip home in special hospital trains the following day.

|

| Letitia arrives at Liverpool from Marseilles on 1 February 1945 with wounded British POWs. Credit: Shutterstock. com |

Her next voyage took Letitia further afield and on new duties when she sailed from Halifax on 4 January 1945 for New York. There, she embarked German POWs for exchange for Allied ones at Marseilles. Letitia left New York on the 7th and arrived at Marseilles on the 24th. Her German POWs were exchanged for an equal number of British/Dominion ones with both groups repatriated via neutral Switzerland by sealed hospital train. Many of the Allied POWs came from camps in Silesia. Letitia embarked 6 stretcher cases and 665 walking cases and sailed for Liverpool where she arrived on 1 February.

|

| Letitia at Liverpool, 1 February 1945 back from her POW repatriation voyage. Credit: inostalgia.com |

Letitia left Liverpool on 13 February 1945 and returned to Halifax on the 22nd with 700 invalided Canadian forces. Subsequent arrivals on 21 March with 746 aboard and 16 April (from Falmouth) disembarked 740 more and on 20 May she came into Halifax with 743 “representing every regiment in Canada,” some who had not been home in five years.

|

| Nurses and medical staff of Letitia, April 1945. Credit: Canada Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-141658 |

With Victory in Europe, the Canadian Government pledged to have every wounded Canadian serviceman, numbering some 53,000, home by 31 July 1945. To help achieve this, the British hospital ship Llandoverry Castle was assigned to join Letitia and Lady Nelson. Letitia came into Halifax again on 17 June with 725 casualties and again on 16 July, two days late due to fog, with 733 and "As the big ship came into her dock, a band on the pierside struck up "Roll Out the Barrel" and spontaneous burst of cheering came from the men lining the rail." (Gazette).

|

| Credit: The Gazette (Montreal) 18 July 1945 |

With eager questions about the Japanese surrender bid, 740 more Canadian veterans from Europe arrived here Saturday [11th] night aboard the hospital ship Letitia.

The ship, her belt of protective lights shining and her red, green and white hull glistening, slipped into her berth without fanfare. There were a few relatives and friends on hand in the shed.

The homecoming of the hospital ship was marred when one of the most popular crew members aboard died as the ship was nearing Canada. He was Hughie MacDougall of Glasgow, steward and member of the Letitia's concert party when she was a peacetime cruise ship. His imitations of Sir Harry Lauder were familiar to thousands of Letitia's passengers.

The Windsor Daily Star, 13 August 1945.

Following her 11 August 1945 arrival at Halifax, Letitia was overhauled for transfer to the Pacific Theatre and after V-J Day, her main mission was intended to be the repatriation of 1,480 Canadian POWs from the Hong Kong garrison which fell on Christmas Day 1941, and most of whom had been taken to Manila to recover enough to travel. The work on Letitia entailed improvements to her ventilation systems, fitting of insect screening over ports, provision of deck awnings and increasing her capacity to 826 patients with the creation of a new 200-bed ward. Her RCAMC personnel was reduced by half and her medical staff now comprised 11 officers, 15 nursing sisters and 70 other ranks.

Letitia sailed from Halifax on 1 September, transited the Panama Canal on the 8th and arrived at Pearl Harbor on the 24th. Crossing the Pacific, Letitia arrived at Tacloban, Philippines, on 12 October and Manila on 6th November. In between all of this, the ship was reported on 23 October to have broken down two days out of Manila with one of her propeller shafts reported broken. On 3 November it was further reported she was at Pearl Harbor with "problems with her refrigerating equipment" and "damage to a propeller" having had to return to the port two days after leaving it. Letitia had rather missed the boat and the Canadian survivors she came all that way to collect were, instead, repatriated by other means.

As turned out, she left Manila with but one of the Hong Kong Garrison men, embarking 695 U.S. Army and Navy wounded personnel, 88 Canadians including Pte. Earl Mossman, last of the Canadian POWs to return, 25 British POWs, French missionaries, British Red Cross nurses and U.S.O. personnel. Letitia's finally arrived at Tacoma, Washington, on 5 December 1945, where she disembarked her American personnel before proceeding to Vancouver where she docked on the 6th .

Letitia sailed from Halifax on 1 September, transited the Panama Canal on the 8th and arrived at Pearl Harbor on the 24th. Crossing the Pacific, Letitia arrived at Tacloban, Philippines, on 12 October and Manila on 6th November. In between all of this, the ship was reported on 23 October to have broken down two days out of Manila with one of her propeller shafts reported broken. On 3 November it was further reported she was at Pearl Harbor with "problems with her refrigerating equipment" and "damage to a propeller" having had to return to the port two days after leaving it. Letitia had rather missed the boat and the Canadian survivors she came all that way to collect were, instead, repatriated by other means.

As turned out, she left Manila with but one of the Hong Kong Garrison men, embarking 695 U.S. Army and Navy wounded personnel, 88 Canadians including Pte. Earl Mossman, last of the Canadian POWs to return, 25 British POWs, French missionaries, British Red Cross nurses and U.S.O. personnel. Letitia's finally arrived at Tacoma, Washington, on 5 December 1945, where she disembarked her American personnel before proceeding to Vancouver where she docked on the 6th .

The scene as the big white liner eased into Pier B was reminiscent of the days before the war when the White Empresses of the Pacific docked at the same berth.

Except for her single funnel and the large red cross painted on her hull, the Letitia looked much like the Asia, or the Russia or the Canada.

Among the passengers was Pvt. Earl Mossman, 36-year-old Nova Scotian, the last of the Canadian prisoners from Hong Kong to arrive back in Canada.

The Province (Vancouver) 6 December 1945

|

| Letitia arriving at Halifax. Credit: http://www.forposterityssake.ca/ |

|

| Course set for a fulsome post-war career: Letitia's helmsman. Credit: National Archives of Canada. |

On 29 November 1945 it was first rumoured that Letitia and Lady Nelson might be employed as Canadian war bride ships. Letitia's new role as such was confirmed on 14 December when it was anticipated she would make three round voyages from the U.K. to Halifax every two months, carrying 400 war brides every crossing. To adapt her to this role, Letitia was sent to Yarrows Ltd., Esquimalt, for a rush conversion. She sailed from Vancouver at 2:00 p.m. on 10 December for Victoria and entered the graving dock at Esquimalt at 8:00 a.m. the next day.

Yarrows Ltd. are overhauling and repairing the engines of the hospital ship, and cleaning and painting the hull. Repair work is being done on a number of plates without removing them from the ship, but further repaits to her plates, reportedly damaged by heavy weather out of Manila, will have to wait until she has completed her scheduled transport of the brides.

The Victoria Daily Times, 17 December 1945

|

| Credit: The Victoria Daily Times, 13 December 1945 |

Having departed for Britain on the 29th, Letitia had only made it as far as William Head when she again developed engine trouble and was forced to return to the yard. Following repairs, Letitia resumed her voyage on 4 January 1946. At the time, it was rather hopefully reported that she would “return to the Montreal-U.K. run sometime this summer.”

Stocked with an assortment of warm clothing, babies' outfites and hospital supplies from Red Cross stores in Vancouver, the Letitia sailed from Esquimalt Friday (28th) en route to Great Britain to pick up its load of wives and children of Canadian service men.

All during the holiday week Red Cross workers in North and West Vancouver and Vancouver proper have worked at high speed making pneumonia jackets for the children and hundreds of disposable diapers that are standard equipment on these boats.

Included in the 25,000 items that were supplied from the Red Cross were complete layettes, warm clothing for young children, extra clothing for mothers, 700 dressing gowns, ward slippers, bed sock, and complete hospital supplies.

With commencement early in the year of transport of these war brides and children from Great Britain, the Canadian Red Cross Society will supply conducting officers to look after the comfort of these new Canadian citizens. In addition, every boat will be outfitted with supplies and new clothes by the Red Cross so that each arrival will be well equipped for travel to her new home as well as her comfort assured during the ocean voyage.

The Vancouver Sun, 29 December 1945

On arriving on the Clyde on 1 February 1946, Letitia had just weighed anchor off the Tail of the Bank to proceed up river to Glasgow when she came into contact with the new hopper barge, Empire Moorehead. There was no serious damage to either vessel and Letitia proceeded to Glasgow. There, her refitting for new new role continued. This included complete repainting in her pre-war livery.

Letitia came alongside Prince's Landing Stage on 22 February 1946 to prepare for her first war bride voyage. Canadian soldiers helped with the loading of baggage while the first of 841 women and children, some with babies in arms, embarked. Letitia sailed from Liverpool the next day with 628 Canadian Army and 185 RCAF dependents. Reaching Halifax late on 3 March, she had to wait off the port until the next morning when Scythia sailed with 2,500 German POWs.

Scythia and Letitia continued to ply the Canadian bride run in perfect tandem. On 18 March 1946 just after the Cunarder sailed from Liverpool with war brides, Letitia berthed with 183 German POWs from Canada, the first such contingent the ship carried.

On her second voyage, Letitia left Liverpool 25 March 1946 with 630 wives and 317 children after a small fire aboard resulting in the banning of smoking throughout the vessel except in public rooms. She docked at Halifax on 2 April.

It was brides out and contraband in apparently. On 17 April 1946 it was reported that the "flying squad" of Liverpool Customs had discovered 50 lbs. of millet seed concealed in the ship as well as silk stockings. The four men suspected of smuggling were discharged from the ship's crew pending further investigation. Letitia sailed for Canada that day 17 hours late after a strike by 50 of her catering staff. They complained that their quarters were ill-ventilated and there was no news bulletins available to them as well as the shore leave being too short. She finally was underway by 10:00 a.m. and docked at Halifax with more than 800 passengers on the 25th.

By May 1946, a total of 340,000 Canadian forces and dependents had been repatriated in the 12 months since VE Day. The work continued and Letitia left Liverpool on 13 May for Halifax with 674 wives and children with subsequent sailings on 17 June (520 brides and 360 children) and 11 July with 481 wives and 421 children. She reached Halifax on the 19th, one of four liners bringing 3,300 to the Dominion. Operation Stork was now at it halfway mark with 25,000 brides still awaiting passage.

An envy inducing brief mention on the Hull Daily Mail of 18 June 1946 stated that "More than 520 brides of Canadian Servicemen who went on board the liner Letitia at Liverpool were wearing fully-fashioned silk stockings-- a present from Canada.

Another 429 brides and 432 children arrived in Letitia on 13 August and 395 wives. On what proved to be her final voyage as such, Letitia sailed from Liverpool on 3 September and docked at Halifax on the 10th with 724 dependents.

Letitia came alongside Prince's Landing Stage on 22 February 1946 to prepare for her first war bride voyage. Canadian soldiers helped with the loading of baggage while the first of 841 women and children, some with babies in arms, embarked. Letitia sailed from Liverpool the next day with 628 Canadian Army and 185 RCAF dependents. Reaching Halifax late on 3 March, she had to wait off the port until the next morning when Scythia sailed with 2,500 German POWs.

|

| Some of the first war brides arriving at Halifax aboard Letitia. Credit: The Gazette (Montreal) 6 March 1946. |

Scythia and Letitia continued to ply the Canadian bride run in perfect tandem. On 18 March 1946 just after the Cunarder sailed from Liverpool with war brides, Letitia berthed with 183 German POWs from Canada, the first such contingent the ship carried.

On her second voyage, Letitia left Liverpool 25 March 1946 with 630 wives and 317 children after a small fire aboard resulting in the banning of smoking throughout the vessel except in public rooms. She docked at Halifax on 2 April.

|

| Mrs. J.W. Perry, a war bride and her daughter Sheila, aboard Letitia. Credit:Barney J. Gloster/Canada. Dept. of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-175790 |

It was brides out and contraband in apparently. On 17 April 1946 it was reported that the "flying squad" of Liverpool Customs had discovered 50 lbs. of millet seed concealed in the ship as well as silk stockings. The four men suspected of smuggling were discharged from the ship's crew pending further investigation. Letitia sailed for Canada that day 17 hours late after a strike by 50 of her catering staff. They complained that their quarters were ill-ventilated and there was no news bulletins available to them as well as the shore leave being too short. She finally was underway by 10:00 a.m. and docked at Halifax with more than 800 passengers on the 25th.

By May 1946, a total of 340,000 Canadian forces and dependents had been repatriated in the 12 months since VE Day. The work continued and Letitia left Liverpool on 13 May for Halifax with 674 wives and children with subsequent sailings on 17 June (520 brides and 360 children) and 11 July with 481 wives and 421 children. She reached Halifax on the 19th, one of four liners bringing 3,300 to the Dominion. Operation Stork was now at it halfway mark with 25,000 brides still awaiting passage.

An envy inducing brief mention on the Hull Daily Mail of 18 June 1946 stated that "More than 520 brides of Canadian Servicemen who went on board the liner Letitia at Liverpool were wearing fully-fashioned silk stockings-- a present from Canada.

Another 429 brides and 432 children arrived in Letitia on 13 August and 395 wives. On what proved to be her final voyage as such, Letitia sailed from Liverpool on 3 September and docked at Halifax on the 10th with 724 dependents.

Donaldson Line had decided against reviving their Glasgow-St. Lawrence passenger service and whilst it continued to manage Letitia, she was sold in September 1946 to the Ministry of Transport to used as a war bride and troop transport and renamed Empire Brent. As a nominal H.M. Transport, her crew was now augmented by 35-year-old Charles Conlogue from Glasgow, Ship’s Bugler, who henceforth announced breakfast with the Navy’s “Cook House” call, luncheon with “Officer Call for Dinner” and dinner with “Retreat”. On 8 October Empire Brent made her “maiden” call at Halifax.

|

| Postcard for Empire Brent using a retouched version of the pre-war Odin Rosenvinge card for Letitia. Credit: Author's collection. |

As Empire Brent, she continued her war bride duties and made her maiden voyage as such from Liverpool on 30 September 1946 with 432 wives and 274 children. As an H.M. Transport, her crew was augmented by 35-year-old Charles Conlogue from Glasgow, Ship’s Bugler, who henceforth announced breakfast with the Navy’s “Cook House” call, luncheon with “Officer Call for Dinner” and dinner with “Retreat.” On 8 October Empire Brent made her “maiden” call at Halifax.

In her most serious accident, on 20 November 1946 Empire Brent collided with and sank the 1,031-ton British cattle steamer Stormont, inbound from Belfast, in the River Mersey at 7:15 a.m. shortly after sailing from the Landing Stage with 900 warbrides aboard. The accident occurred just after Empire Brent had let go her tugs and steaming slowly down the river as Stormont was coming up in the opposite direction. When a collision seemed inevitable, the liner's engines were put in full reverse and her anchors let go, but it was too late. Hit and holed on her starboardside, Stormont healed over dangerously after the impact and she was grounded on the north end of Pluckington Bank. When it was attempted to place the vessel alongside Albert Dock, she capsized 200-300 yards off the dock.

|

| The Belfast registered Stormont capsized off Pluckington Bank after her collision with Empire Brent. Credit: shipsnostalgia.com, member kingorry. |

Although all of her crew were saved, there were disturbing scenes as 210 head of cattle struggled in the river, some were saved, but sadly some 200 drowned or were shot when they could not be hauled into the rescue boats. Others were trapped in the vessel. Some of her cargo including 30,000 tons of evaporated milk was salvaged. The ship’s two kittens, Blackie and Whitie, were found safe, having climbed onto a shelf as the ship half submerged and were adopted by the crew of the salvage vessel Salvor.

Empire Brent was badly damaged with her stem bent around some 12 ft. above the waterline as well as extensive damage below the waterline. The ship returned to port and was moored at Alfred Dock. After spending the night aboard, the passengers were taken by special train to London where they were accommodated until ship can be repaired and sail. They re-embarked on 3 December 1946 and sailed the following morning. She arrived at Halifax on the 13th with 874 war brides and children.

|

| Empire Brent had her stem crushed 12 ft. above the waterline and suffered underwater damage as well. Credit: Liverpool Echo, 20 November 1946. |

Empire Brent was badly damaged with her stem bent around some 12 ft. above the waterline as well as extensive damage below the waterline. The ship returned to port and was moored at Alfred Dock. After spending the night aboard, the passengers were taken by special train to London where they were accommodated until ship can be repaired and sail. They re-embarked on 3 December 1946 and sailed the following morning. She arrived at Halifax on the 13th with 874 war brides and children.

This proved to be the ship’s final “Operation Stork” voyage and her last Canada landfall for almost nine years. In all, Letitia/Empire Brent made ten "Operation Stork" voyages from the U.K. to Canada, carrying a total of 7,644 war brides and their children.

Empire Brent was now to engage in wide ranging troop and displaced person voyages as the shattered post-war world struggled to return to some normalcy.

Before undertaking her new duties, Empire Brent underwent a major six-month refitting and repair at Barclay, Curle’s Elderslie yards beginning in mid January. This entailed finally restoring to “as new” her still battered underwater hull following her 1943 grounding at Alexandria. Her wartime life rafts were removed and her funnel was repainted in all black. New blading was fitted to both her high-pressure turbines. The refit was detailed in an extensive newspaper account:

Empire Brent Refitted

Barclay, Curle and Co. are proud of their achievement in repairing and refitting for the specified date the Empire Brent, the 13,500-ton liner which was built on the Clyde as the Letitia. The vessel had sustained extensive bottom damage in 1943, which was temporarily repaired on the other side of the Atlantic, some bow damage in a recent collision in the Mersey, and was in hand for conversion from hospital work to special Admiralty service.

As the bottom damage extended from the keel to the turn of the bilge on both port and starboard sides, its repair involved removal and renewal of 14 keel plates and 105 shell plates-- a task which was completed in five sections. Floors and frame from the forepeak bulkhead to the afterpeak bulkhead were renewed.

The balanced type rudder was removed for examination; all the double-bottom tanks and side oil fuel tanks and bunkers were tested; the tail shafts were drawn for examination and replaced; the turbines were removed and new blading fitted to the port and starboard high-pressure rotors and to two rows of the low-pressure rotor; the auxiliaries were overhauled; boilers were surveyed and air tubes renewed; hospital fittings were stripped out and new accommodation fitted; and the ship went through the special survey.

On February 10 last the Empire Brent was drydocked at Elderslie. She was undocked on June 12 and, with the repair work completed afloat, successful dock trials were carried out last Thursday (10 July) and sea trials on Saturday (12th). The liner takes up her new service next Monday (21st) which was the date specified in the contract.

The Glasgow Herald, 15 July 1947

Empire Brent’s first sailing on 21 July 1947 would take her from Liverpool to Suez, East Africa, Mauritius and Bombay. This was delayed to await the arrival of a special train conveying some 300 passengers whose original London Euston-Liverpool train was involved in a spectacular derailment in Warwickshire. Reaching Mombasa on the 11th, Empire Brent continued to Bombay where she embarked 968 Polish displaced persons who had been evacuated first from camps in Palestine six months previously. Empire Brent returned to Southampton on 26 September and Glasgow on 1 October. Another voyage to Bombay ensued where she arrived on 5 November and routed home via Colombo, arrived at Liverpool on 28 November. She had aboard another large group of 779 Polish civilians and 192 members of the Polish Forces who had embarked in Bombay.

In December 1947 there was a flurry of news reports on proposals put forward by the Scottish Tourist Board to secure the release of the vessel from Ministry of Transport so she could be refitted and restored to her direct Glasgow-Canada run.

Instead, under a one-voyage charter to P&O for their Far East Mail Service, Empire Brent sailed on 19 December 1947 from Glasgow to Bombay, Colombo (arriving 12 January 1948), Singapore (16), Hong Kong and Shanghai where she docked on the 27th. She left Shanghai on 4 February, called at Singapore, Penang, Colombo and Bombay and returned to Liverpool on 8 March with nine of her child passengers taken to hospital suffering from measles.

|

| Empire Brent's maiden arrival in Australia in May 1948 showing her all-black funnel dating from her refit. Credit: Australian War Memorial. |

Scotland’s tied with Australia, already strong, will be linked still closer when for the first time in the history of migration to the Commonwealth, an emigrant ship will sail direct from Scotland.

The Herald (Melbourne), 30 March 1948

Among the earliest Empire immigrant schemes was that organised in 1920-1939 by the Australian Government in co-operation with the State Governments that offered assisted passage to qualified British migrants, the so-called called “Ten Pound Poms” reflecting the flat fare paid. A new scheme came into operation on 31 March 1947 to which the British Government contributed £550,000 towards the cost from March 1947-March 1952 and then £150,000 yearly through 1955. The first year only 11,000 migrants came in, owing mostly to a shortage of available berths on scheduled services. It was then decided, in co-operation with the Ministry of Transport, to create a dedicated fleet of migrant ships chartered to the Australian Government. This was announced on 2 January 1948 by Australia’s Minister of Immigration.

Among the ships to be chartered would be Empire Brent which was to make the first of three voyages in April 1948. On 10 February it was stated that she would remain “indefinitely” on the migrant run and on 4 March her first voyage was set for the 31st from Glasgow, the first migrant vessel ever to sail directly from Scotland to Australia. She was programmed to make four voyages annually and would be refitted to accommodate 965 passengers in dormitories.

Empire Brent returned to Glasgow on 11 March 1948 from Liverpool and her voyage to the Far East and berthed at Merklands Wharf where she was readied for her role.

The Empire Brent is well suited to this type of work. Since she was overhauled and refitted by Barclay, Curle and Co., Ltd., between December, 1946, and June, 1947, she has been carrying civilian passengers for the Ministry of Transport.

Glasgow Herald, 11 March 1948

Empire Brent’s first voyage, departing Glasgow 31 March 1948, would call en route at Bombay to disembark 70 commercial passengers and embark a similar number of emigrants. All of the other passengers would be sponsored by Australia House and bound for Fremantle, Melbourne and Sydney.

After surrendering their ration books, identity cards, clothing coupons, and other documents, 900 emigrants on their way to Australia walked up the gangways to a liner at Glasgow yesterday. The vessel, the Empire Brent, was due to leave early this morning with the travellers, the biggest mass emigration from the Clyde in many years."

"It was raining heavily as the emigrants went aboard, and there seemed no regrets at leaving home and starting like on the other side of the world. Most of them looked upon the change as affording new opportunities in a new land.

The Scotsman, 1 April 1948

So it was reported the day after 900 migrants (half of whom were Scots) trooped aboard Empire Brent at Glasgow’s King George V Dock on 31 March 1948. They arrived at Fremantle on 2 May 1948, greeted by pipers playing on the quayside, where 45 disembarked. The local press reported effusive praise for the vessel and conditions aboard "Migrants said the ship's officers and crew did everything to make the trip pleasant", "The food was excellent and was at least twice the British ration" and “Ship was heaven”. There had been an outbreak of chicken pox aboard, affecting 40 passengers, mostly children, which kept the ship’s surgeon and one nurse busy. She arrived at Melbourne on 7th, and Sydney the 10th.

|

| A sampling of the New Australians arriving in Empire Brent on her first voyage to Australia. Credit: The Argus 8 May 1948 (Melbourne). |

Empire Brent left Sydney on 20 May 1948 and return via Bombay (4 June) and Aden (8th) and arrived back at Glasgow on 24 June. Among her passengers was India’s first Olympic Team bound for the London Games:

India's athletes were a motley crowd when they got aboard this troopship, still not fully restored to its peace-time dignity, on sultry afternoon of June 4 at Bombay. But spirits were high for the great adventure ahead.

The athletes had cabins on the fourth deck-- some way below water level. It was 'stinking hot,' so the second night they rolled about and counted stars from the open deck.

Early up, they got busy right away at P.T., with skipping ropes, medicine balls and what not. The next morning the attendence was not so good.

Sea-sickness, that bane of all landlubbers, had taken its toll-- a heavy toll. Mysore's hop, step man and the country's main hope, Henry Rebello, was the worst affected. The heavy men-- the strong men-- were also reduced to the common level.

Worse was to follow. The Empire Brent soon ran into stormy weather, and despite its 17,000 tons seemed to have no answer for the monsoon waves, and one and all were nearly rocked to panic. Full 0 hours elapsed before the water flattened out.

Life soon became worth living again and food began to taste like food again although I could scarcely repress a grin when some of the boys, after wrestling with the impressive French titles on the menu, discovered they to have cold meat and fish, afterall.

I felt rather sorry that they had not been forewarned to take extra rations. They soon began to feel the pinch. Sugar, particularly, is as precious commodity aboard as an Olympic medal will be later on.

We touched Aden today. Tomorrow it will be back to P.T. on deck, etc. for them.

The Indian Express, 22 June 1948.

Empire Brent sailed again for Australia from Glasgow on 13 July 1948, arriving Sydney, via Fremantle and Melbourne, on 20 August. On the homeward passage commencing seven days later, she was routed via Bombay (arriving 12 September) and Karachi where she embarked returning troops and British civilians and docked at Liverpool on 5 October.

|

| Migrants being greeted and disembarking from Empire Brent in Australia, August 1948. Credit: Library of New South Wales. |

Her next outbound voyage with migrants reached Fremantle on 17 November 1948 and returned to Liverpool on 7 January 1949. After a refit, Empire Brent was off again to Australia on 8 February with a record 1,000 passengers, including 200 children. Not all those who “went out” to a new life in the Antipodes settled happily and there was a small but steady stream of “returners” on the northbound voyages. On 29 April Empire Brent disembarked 150 passengers at Glasgow, most of them returning immigrants including a “Mrs. Donaldson who thought life in New Zealand very dull. Shopping conditions were poor and the people had a very poor sense of humour.” (Dundee Evening Telegraph).

Empire Brent was temporarily commanded by Capt. M.H. McLachlan on a round voyage departing 14 May 1949 as a leave replacement and he passed away suddenly at sea on 13 June 1949 and was buried at sea before the vessel docked at Fremantle with 964 migrants.

Starting her sixth voyage as an Australian migrant ship, Empire Brent sailed from Glasgow on 17 August 1949 with 940 passengers, a third of whom were Scots.

The ship continued to vary her homeward passages as there was very little demand for northbound berths. On 1 October 1949 Empire Brent sailed from Sydney for Glasgow, but with a twist… a diversion on charter to the Netherlands Government to repatriate Dutch army and navy personnel from Indonesia as the former Dutch East Indies entered into a turbulent decade of independence, revolution and upheaval. She called at Fremantle on the 7th for bunkers and proceeded to Batavia where she arrived on the 12th. After embarking 913 personnel, Empire Brent sailed for the Netherlands on the 14th along with Waterman.

|

| Empire Brent arriving in Sydney in pre Opera House days! Credit: www.shf.org.au |

The ship continued to vary her homeward passages as there was very little demand for northbound berths. On 1 October 1949 Empire Brent sailed from Sydney for Glasgow, but with a twist… a diversion on charter to the Netherlands Government to repatriate Dutch army and navy personnel from Indonesia as the former Dutch East Indies entered into a turbulent decade of independence, revolution and upheaval. She called at Fremantle on the 7th for bunkers and proceeded to Batavia where she arrived on the 12th. After embarking 913 personnel, Empire Brent sailed for the Netherlands on the 14th along with Waterman.

Empire Brent docked at Amsterdam on 10 November 1949 and the ship, crew and conditions aboard were praised in the Dutch newspapers:

People on board full of praise for accommodation. The Dutch government has been successful in chartering English ships to bring the Dutch troops back from Indonesia to the Netherlands. This was evident from the mood that prevailed yesterday morning during the debarkation of the first English 13,595-ton ship, the Empire Brent. All officers and men, without exception, are extremely satisfied with the treatment, location and nutrition on the ship. What had been most feared, namely that the English diet would be displeased, has turned out to be completely unfounded. The men, as they themselves say, are "spoiled on this ship." Not only did the food fare well, but also the location - all soldiers were stationed in rooms - and the stewards and cooking services were not necessary on this ship, because the crew took care of these works - has been very popular. Salons were available for the troops, a lot of recreation room, a large library with 800 books. New films were shown along the way. Also Captain James Cook is very satisfied with the behavior of the Dutch soldiers and found this trip, on which he transported about 700 soldiers with their families and some civilians, a total of about 900 persons, much more comfortable than the trips he made during the war with the Empire Brent when the ship carried 3,000 soldiers at a time. The Empire Brent set sail again yesterday afternoon at 2 am to Glasgow to bring emigrants to Australia in a fortnight. On the return voyage, the Empire Brent will again bring troops from Indonesia and bring them back to the homeland.

Het Neiuwsblad Van Het Zuiden, 11 November 1949

|

| Some of the Dutch soldiers who returned from Batavia aboard Empire Brent. Credit: Wikimedia Commons. |

Back on her more familiar duties, Empire Brent cast off again from Glasgow on 29 November 1949 for Australia. En route she had had put into Malta on 6 December to land a critically three-year-old child. She had been in the ships hospital for four days with an abdominal complain which suddenly became acute. Upon the ship's arrival in Adelaide, a message was received that the child had recovered and been discharged. Empire Brent docked at Sydney on 7 January in the middle of another dockers strike and the ship’s 200 stewards had to unload the 500 passengers luggage.

Destined again for Batavia via Fremantle, Empire Brent left Sydney on 14 January 1950 and arrived at Tjanjong Priok on the 26th. She docked at Amsterdam on 21 February and the following day disembarked 913 military personnel.

|

| Wonderful "snaps" aboard Empire Brent on one of her Batavia-Netherlands voyages c. 1948-50 by a soldier returning home aboard her. Credit: https://www.indiegangers.nl/ |

Empire Brent was off again to Australia on 6 April 1950. When she arrived at Sydney on 17 May, local newspapers reported that when she had docked at Adelaide the previous weekend there were complaints from some of the 950 aboard over the standard of food and overcrowding. In addition, “inadequate hospital and medical facilities aboard” were alleged to have contributed to the deaths of two ill passengers. She departed Sydney on the 23rd and this homeward voyage, too, was routed via Batavia where she docked on 4 June. Empire Brent docked at Rotterdam on 3 July where she disembarked 760 military passengers (troops and dependents) and 235 civilians with 381 children under the age of 12 aboard. Sadly, two babies died during the course of the voyage.

What would prove to be Empire Brent’s final voyage proved eventful from the beginning. Two hours before embarkation began from Glasgow’s King George V Dock on 22 July 1950, fire broke out in no. 7 hold. Four fire engines and a fire boat got the fire under control, but a senior fire brigade was injured when he fell 15 ft. through an open hold onto an oil tank cover and taken to hospital with back injuries. The ship sailed on schedule.

Empire Brent arrived Fremantle on 23 August 1950 with 738 British and 200 Dutch migrants including eight additional members of the Plug family, 19 others arrived previous week in the Dutch liner Sibajak and in all, 39 of the same family emigrated to Australia by years end.

The final part of her voyage was tedious. Engine trouble delayed her Adelaide arrival until 28 August 1950, two days late, by which time the harbour had ground to a standstill due to a strike by dock workers and tug boat crews. An engineer was flown out from Sydney to assist with the repairs to her machinery but the ship remained off Semaphore anchorage. In the end, Empire Brent did not dock until 9:00 a.m. on the 31st and sailed for Sydney the next day where she finally arrived the afternoon of the 5th. The last of her landing migrants described the trip as a “nightmare”.

Empire Brent was shifted on 12 September 1950 to Cockatoo dockyard for repairs. She finally sailed for home on 12 October, but with a major deviation when, after bunkering at Fremantle on the 20th, she again proceeded to Batavia via Colombo (5 November), Aden (13) arriving on the 21st. She departed for Rotterdam on the 28th but again her machinery played up and she made much of the voyage on one engine, the passage via Colombo and Aden taking some five weeks. Finally, on 3 December she docked at the Lloydkade, Rotterdam, to disembark some 1,000 passengers, including 400 children. A 79-year-old passenger had died aboard of a heart condition and was buried at sea.

After a long absence, Empire Brent returned to Glasgow on 5 December 1950. Duty done for now, she was laid up at Stobcross, Glasgow. For the former Letitia, it was the first respite in her 25-year-career.

|

| Empire Brent laid up at Stobcross, Glasgow c. December 1950-July 1951. Credit: via www.merchant-navy.net |

T.S.S. CAPTAIN COOK

NEW ZEALAND MIGRANT SHIP

The movement of people throughout much of the post-war world continued unabated. In addition to Australia, New Zealand promised a new beginning for many Britons. In mid 1948, New Zealand (whose population at the time was under two millions) adopted a subsidised emigration scheme not unlike that of Canada during the inter-war years. Towards this end, £592,000 was allocated by the Government to provide free passage out to qualified settlers and charter a ship to cater exclusively to emigrants. This was the once fabled Royal Mail liner/cruise ship Atlantis which was chartered from the British Ministry of Transport in 1948 for four years to carry emigrants from Britons to Wellington, New Zealand, via Suez and Fremantle. In 1951, some 3,000 Britons came to New Zealand on the scheme which was reckoned to cost the country £200 a head.

NEW ZEALAND MIGRANT SHIP

I sailed on the Captain Cook arriving in Wellington Nov 1958. Wonderful trip through the Panama Canal.. food was good, ship really clean. Did our washing and had washing lines up on deck. Passengers made their own entertainment. There was dancing, piano recitals....we did a wonderful show at the end of the trip singing "At Sea on the Captain Cook....Every morning the stewards brought cups of tea to the cabins..saying "Rise and Shine on the Donaldson Line" Always remember the food.... hands up for eggs? in the mornings.

https://nzhistory.govt.nz

After 38 hard years, Atlantis was worn out and to replace her, the New Zealand Government in cooperation with the Ministry of Transport decided in summer 1951 to refit both Empire Brent and the former Henderson liner Amarapoora for a new migrant service from Southampton to Wellington via the Panama Canal instead Suez. On 12 June New Zealand's Minister of Immigration, W. Sullivan, announced the purchase of Empire Brent which after a conversion estimated to cost £500,000 was expected to make her first voyage in November. A month later the acquisition of Amarapoora was revealed and she would come on line in February 1952. The faster Donaldson Line ship would make four round voyages a year while the 14-knot Henderson ship, three.

Empire Brent was moved to the Barclay, Curle Elderslie yards for a six-month £750,000 refit and rebuilding for her new duties. This entailed a complete gutting of her dormitories and installation of all new accommodation with two, four and six-berth cabins for 1,088 passengers, all of which had wash basins with hot and cold running water, wardrobes and dressers, but were very plainly "decorated" with open overheads and linoleum decking. The existing Thermotank ventilation system was overhauled and expanded but was never able to cope with her new route via the Caribbean and Panama. Allocation of cabins was families on the upper decks, single women forward and single men after in the lower decks.

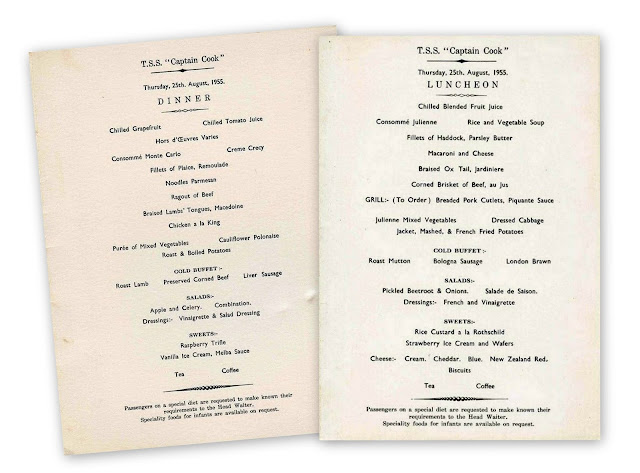

Most of Letitia’s original Cabin Class public rooms remained intact and were attractively refurbished and restored. The dark paneling of the original smoking room was painted in light pastels, new flooring, lighting and furnishings installed in all the rooms. In all, her passengers had at their disposal five lounges, smoking room, writing room, nursery and ironing room. The two dining saloons (the forward one retaining its original Tudor décor) offered two-sittings for meals. Films were often showed on deck with a large screen erected between the aft kingposts, but most of the entertainment was organised by the passengers to break the monotony of what was a very long voyage with few port calls en route.

On 18 September 1951 Empire Brent was renamed Captain Cook (Amarapoora was renamed Captain Hobson). But progress on their conversions lagged owing to the steel shortage in Britain and plans to have Captain Cook begin service in November and then December were dropped. On 17 November it was announced that she would not make her first voyage until late January 1952 at the earliest with Captain Hobson not until mid April instead of February.

|

| T.S.S. Captain Cook in Wellington Harbour. Still managed by Donaldson Line and registered in Glasgow, the ship was also restored to full Donaldson livery. Credit: New Zealand Library. |

Empire Brent was moved to the Barclay, Curle Elderslie yards for a six-month £750,000 refit and rebuilding for her new duties. This entailed a complete gutting of her dormitories and installation of all new accommodation with two, four and six-berth cabins for 1,088 passengers, all of which had wash basins with hot and cold running water, wardrobes and dressers, but were very plainly "decorated" with open overheads and linoleum decking. The existing Thermotank ventilation system was overhauled and expanded but was never able to cope with her new route via the Caribbean and Panama. Allocation of cabins was families on the upper decks, single women forward and single men after in the lower decks.

Most of Letitia’s original Cabin Class public rooms remained intact and were attractively refurbished and restored. The dark paneling of the original smoking room was painted in light pastels, new flooring, lighting and furnishings installed in all the rooms. In all, her passengers had at their disposal five lounges, smoking room, writing room, nursery and ironing room. The two dining saloons (the forward one retaining its original Tudor décor) offered two-sittings for meals. Films were often showed on deck with a large screen erected between the aft kingposts, but most of the entertainment was organised by the passengers to break the monotony of what was a very long voyage with few port calls en route.

|

| Captain Cook, believed taken on her post-refit trials in the Clyde on 29 January 1952, and part of a souvenir set of postcards of the ship. Credit: Author's collection. |

|

| The Main Lounge, formerly the Cabin Class Smoking Room with its original oak panelling painted over in pastel enamel. Credit: Author's collection. |

|

| The Drawing Room, largely unchanged except for the more contemporary furnishings and the comparative luxury of fitted carpeting. Credit: Author's collection. |

|

| The Writing Room, one of the forward corridor rooms. With but two port of calls en route, Curaçao and the Panama Canal, opportunities for posting mail were few. Credit: Author's collection. |

|

| The Corridor Lounge which had new panelling as well as decking and furnishings. Credit: Author's collection. |

On 18 September 1951 Empire Brent was renamed Captain Cook (Amarapoora was renamed Captain Hobson). But progress on their conversions lagged owing to the steel shortage in Britain and plans to have Captain Cook begin service in November and then December were dropped. On 17 November it was announced that she would not make her first voyage until late January 1952 at the earliest with Captain Hobson not until mid April instead of February.

In one of the wonderful coincidences, on 20 December 1951 it was confirmed that Captain Cook's master would be no none other than Donaldson's Capt. James Cook who had also been master of Athenia at the time of her torpedoing. A Captain Cook with a Captain Cook in command ensured a 27-year-old migrant ship got more her share of press mention. And to make it an even better story, the present Capt. Cook was actually related to the Capt. Cook.

The ship, now measuring 13,876 grt, remained Donaldson managed and was repainted in full Donaldson Line colours and still registered in Glasgow. Captain Cook's maiden voyage, from Glasgow, was set for 15 January 1952. The ship ran trials in the Firth of Clyde on the 29th.

At a function aboard yesterday Mr. I. Harvey S. Black, a director of Donaldson Brothers and Black Ltd., managers of the Captain Cook, pointed out the New Zealand Government had spent £750,000 to bring the ship to the condition in which she had been inspected that day by a large party of press representatives and others. A great number of improvements had been made, including the complete overhaul of the Thermotank system. She was to be regarded as a passenger ship for the use of young settlers going to New Zealand.

The Glasgow Herald, 5 February 1952

|

| Credit: Aberdeen Evening Express, 5 February 1952 |

|

| Captain Cook departs Willemstad, Curaçao; a refuelling stop and her only port of call all the way from Glasgow to Wellington. Credit: eBay auction photo. |

The 13,000-mile, 33-day voyage, called outbound at Curaçao (where she refueled) and the Panama Canal. From the Pacific side of the Canal to Wellington was an unbroken 16 days at sea. Not infrequently, however, Captain Cook would pause briefly in mid Pacific at Pitcairn Island to land stores and mail.

|